Climate mainstreaming of the EU budget was introduced in the Commission’s Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) proposal for the period 2014-2020 which first put forward the idea that “the optimal achievement of objectives in some policy areas – including climate action, environment, consumer policy, health and fundamental rights – depends on the mainstreaming of priorities into a range of instruments in other policy areas” (COM(2011)500). The Commission advocated in particular that the EU budget could play an important role in catalysing the specific investments needed to meet the EU’s climate targets and to ensure climate resilience.

The policy fiche on climate action in the Annex to the 2011 MFF proposal included the idea that the proportion of EU budget spending contributing to the EU’s transition to a low carbon and climate resilient society should be increased to at least 20%, subject to impact assessment evidence. This at least 20% target was endorsed in the European Council conclusions in February 2013 adopting the 2014-2020 MFF.

In making its more recent MFF proposal for the period 2021-2027 in May 2018, the Commission proposed, in line with the Paris Agreement and the commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, to set a more ambitious goal for climate mainstreaming across all EU programmes, with a target of 25% of EU expenditure contributing to climate objectives. This target was endorsed in its European Green Deal Communication as a contribution to the overall increase in annual investment (estimated at €260 billion per annum or 1.5% of EU GDP) required to achieve the EU’s current energy and climate targets.

Spending under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is expected to make up a substantial share of the overall EU budget contribution to the Green Deal, between 40-45% of the total. This post investigates the plausibility of this figure. It argues that the Commission’s methodology set out in the draft CAP Strategic Plan Regulation to assess the climate relevance of CAP expenditure in the 2021-2027 period is not appropriate and likely exaggerates the climate contribution of this expenditure. Given the important role of CAP spending in the expected EU budget contribution to mobilising investment of €1 trillion over the next decade, this issue needs to be addressed by amendments to the draft Regulation.

We proceed in three stages. First, the way the Commission assesses the climate relevance of CAP spending in the current MFF 2014-2020 is explained. Second, the proposed change in the draft Strategic Plan Regulation is described. Finally, some suggestions for possible amendments to improve the situation in the future CAP are put forward.

CAP climate-related expenditure 2014-2020

For the tracking of climate-related expenditure, the Commission took over an existing OECD methodology called ‘Rio markers’ that the OECD had developed to track climate-related development assistance expenditure. This called for the use of three categories: climate related only (100%); significantly climate related (40%); and not climate related (0%) but did not exclude the use of more precise methodologies in policy areas where these are available.

The Commission climate markers approach is described in the 2020 Draft General Budget as follows:

The climate tracking is done using EU climate markers, which adapted the OECD’s development assistance tracking ‘Rio markers’ to provide for quantified financial data. EU climate markers reflect the specificities of each policy area, and assign three categories of weighting to activities on the basis of whether the support makes a significant (100%), a moderate (40%) or insignificant (0%) contribution towards climate change objectives. At the same time, the tracking methodology has also reflected the specificities of policy areas.

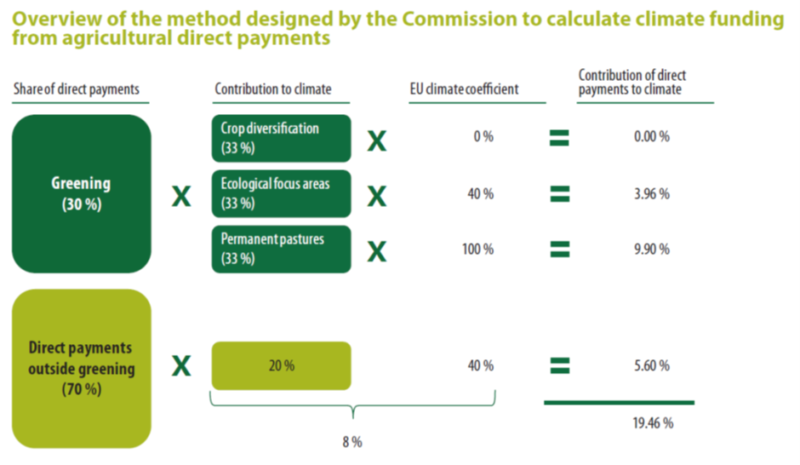

Climate markers in EAGF spending. The Commission assumes that, for European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) expenditure, the practices supported by the greening payment and the cross-compliance required for direct payments both contribute to climate action, using the following climate markers:

- Expenditure under the greening payment is divided

into three equal tiers, linked to the three compulsory farming practices. The tiers

receive the following climate markers, which take into account the estimated

climate contribution (both mitigation and adaptation) of the practices concerned.

- Crop diversification tier: 0%

- Ecological focus area tier: 40%

- Permanent grassland tier: 100%

- For the remaining 70% of direct payments (though

not including payments under the Small Farm Scheme where farmers are not

subject to cross-compliance), the Commission assumes that some of the legal

requirements and Good Agricultural and Environmental Condition (GAEC)

requirements have climate benefits. It applies a 40% marker to the 20% of these

payments potentially at risk to farmers from an initial failure to comply. This

leads to a 19.5% average marker for EAGF expenditure, calculated as follows:

- 100%*10% = 10% (permanent grassland)

- 40%*10% = 4% (EFAs)

- 40%*70%*20% = 5.6 % (cross-compliance)

Source: Explanation of the methodology for applying climate tracking to direct payments, European Court of Auditors, 2016

Climate markers in EAFRD spending. In the case of the European Structural and Investment Funds, including the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), the detailed application of climate markers is set out in Commission Implementing Regulation 215/2014 in Article 2 and Annex II, as follows:

- Support farm risk prevention and management: 40%

- Restoring, preserving and enhancing ecosystems related to agriculture and forestry (Priority 4, all focus areas): 100%

- Promoting resource efficiency and supporting the shift towards a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy in the agriculture, food and forestry sectors (Priority 5, all focus areas): 100%

- Fostering local development in rural areas: 40%

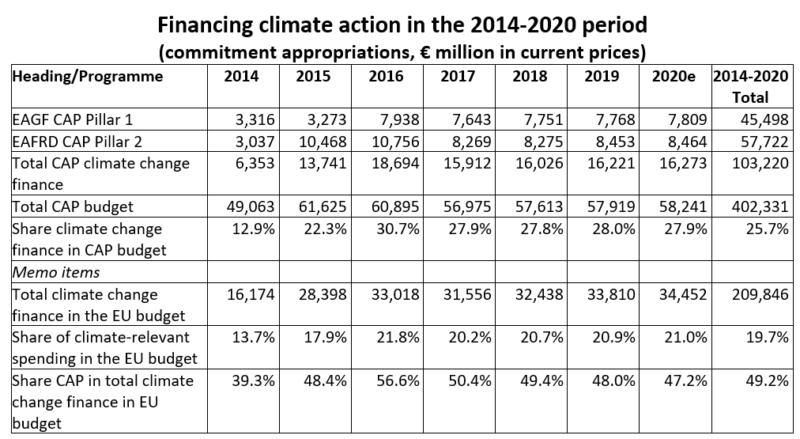

On the basis of these climate markers, the Commission estimates the amounts and percentages of the CAP budget that help to deliver climate action shown in the following table. We will return to some of these percentages later in this post. For the moment, note that around 28% of the CAP budget in recent years is estimated to be climate-relevant using the climate markers devised by the Commission and applied to the specifics of CAP expenditure (the lower figure for 2014 is mainly due to the delay in introducing the greening payment, so that only the cross-compliance contribution for EAGF payments was included in that year).

Overall, the Commission has almost reached its target of 20% of the budget devoted to climate-relevant spending in the MFF period, with the CAP contributing almost half of this amount.

Critical comments of the European Court of Auditors

In 2016, the European Court of Auditors (ECA) reviewed the Commission’s practice of tracking climate-related expenditure in the EU budget. In its remarks on the EAGF climate markers, it accepted that the method and climate markers associated with the greening payment fairly reflected the climate-relatedness of the three farming practices. For the cross-compliance element, it noted there was a lack of appropriate justification particularly for the assumption that 20% of the direct payments had a significant relationship to climate action and it recommended a more conservative assumption.

The ECA was also critical of the Commission’s assumption that all expenditure under Priority 5 ‘Protecting ecosystems’, which also includes payments for areas under natural constraints, justified a climate marker of 100%. For example, ANC payments are intended to prevent land abandonment and, while the Court accepted they could help to prevent climate change, that was not their primary objective and therefore a 40% marker would be justified. The Court developed an alternative matrix where markers were applied at the measure level rather than by priority and focus area. Using this alternative approach, it estimated that the Commission’s estimate of EAFRD climate-related spending would be reduced by 42%.

The Commission responded that it believed its use of climate markers was appropriate and did not lead to over-estimation of the climate-relevance of CAP expenditure. Specifically on the Court’s recommendation that EAFRD tracking should be carried out on a measure level rather than by priority and focus area, it noted that the Court’s proposed approach of applying different climate coefficients to different measures/operations within specific focus areas and Union Priorities would increase the accuracy, but would also lead to an increase of the administrative burden on national and regional administrations.

CAP climate-related spending in the European Green Deal

As noted above, the Commission proposes to increase the share of climate-related expenditure from 20% to 25% in the next MFF. This might seem to be a relatively small increase, but the bulk of climate expenditure in the current MFF is spent on CAP and cohesion funds. These programmes will be slightly reduced in the next MFF, while increases will take place in areas such as security and migration where it is harder to define climate elements. Against this background, the Commission has proposed to increase the share of climate expenditure in the CAP in the next MFF to 40% (compared to 28% share in commitment appropriations in the last years of the current MFF, see table above).

Thus, spending under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is expected to make up a substantial share of the overall EU budget contribution to the Green Deal. Under its Sustainable Europe Investment Plan published earlier this month, the Commission aims to mobilise at least €1 trillion in current prices over the coming decade. This amount is a simple extrapolation over 10 years of the Commission’s 2021-2027 MFF proposal for the first seven years, thus implying investment of €700 billion during the MFF programming period.

Of this, 25% will come from the EU budget earmarked for climate action, for a total of €320 billion in the 2021-2027 MFF period. In fact, the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan envisages an investment of €503 billion over 10 years from the EU budget, or pro rata €352 billion over the MFF period. The difference, as far as I can see, is made up by the EU budget contribution to the Just Transition Mechanism (which is proposed as additional to the MFF budget proposal) plus additional environmental expenditure of €39 billion over a ten-year period.

The total CAP budget is fixed at €365 billion in current prices in the Commission’s 2021-2027 MFF proposal, though this figure remains contested in the ongoing negotiations. If 40% of this amount is available to support climate-related objectives, this would contribute €146 billion of the anticipated €320 billion in the EU budget for climate action (46%) or 41% of the expected EU budget contribution to the investment to be mobilised for the Green Deal including the Just Transition Mechanism and environmental objectives. The first percentage figure, the CAP’s share of climate finance in the total EU budget, is very close to its share of the EU budget in the 2014-2020 MFF.

How robust are the climate markers proposed for the CAP budget?

The EU budget is expected to provide 50% of the total investment to be mobilised under the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan, and the CAP in turn is expected to make up around 41% of the EU budget contribution. But this depends on the assumption that 40% of CAP spending will itself be climate-relevant. How likely will this be the case?

This 40% commitment is not legally binding, but appears in the preamble to the draft Strategic Plan Regulation (Recital 52) which notes that “Actions under the CAP are expected to contribute 40% of the overall financial envelope of the CAP to climate objectives”. It will be one of the parameters used by the Commission in evaluating and approving draft Strategic Plans submitted by the Member States. Thus, one source of uncertainty is that the way Member States intend to programme CAP expenditure under their Strategic Plans is not yet known.

More important is that this commitment to higher climate-related expenditure in the next CAP will be achieved by a sleight of hand. The Commission proposes to significantly increase the climate markers applied to agricultural spending and particularly direct payments without any clear rationale.

On this occasion, all the climate markers and not just those for EAFRD spending will be included in legislation (Article 87 of the draft Strategic Plans Regulation).

- 40% for expenditure under the Basic Income Support for Sustainability and the Complementary Income Support measures;

- 100% for expenditure on eco-schemes in Pillar 1;

- 100% for expenditure on interventions addressing the three specific objectives contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation including sustainable energy; encouraging sustainable management of natural resources such as water, soil and air; and protecting biodiversity and ecosystems, in Pillar 2;

- 40% for expenditure for natural or other area-specific constraints.

While the Commission has partly taken the criticism of the European Court of Auditors into account by reducing the climate weighting of payments for areas of natural constraints to 40%, it proposes to dramatically increase the climate-relevance of direct payments justifying a weighting of 40% by reference to enhanced conditionality. This increase is only partly countered by the exclusion of coupled payments and income support for young farmers from the calculation.

But the requirements for enhanced conditionality are, by and large, mainly the combination of cross-compliance and the greening practices in the current CAP to which the Commission assigned a climate weighting of 19.5%, a percentage which the Court of Auditors had already criticised as too high. There is no justification for increasing the weighting further from 19.5% to 40% except to allow Member States to massage the figures and make it look as though they are doing more for climate than they actually are.

Needless to say, the European Court of Auditors repeats its criticism in its Opinion on the Commission’s CAP draft legislation:

The biggest contribution to the expenditure target is the weighting of 40% for basic income support. This estimate is based on the expected contribution from ‘conditionality’, the successor to cross-compliance and greening. We have already questioned the justification for the corresponding figure from the current period – 19.46%– and reported that it is not a prudent estimate. Hence, we find the estimated CAP contribution towards climate change objectives unrealistic. Overestimating the CAP contribution could lead to lower financial contributions for other policy areas, thus reducing the overall contribution of EU spending to climate change mitigation and adaptation. Instead of using the weighting of 40% for all direct payment support, a more reliable way to estimate the contribution would be to use this weighting only for direct payment support for areas where farmers actually apply practices to mitigate climate change (for example, protecting wetland and peatland).

Conclusions

The European Green Deal is this Commission’s defining priority. As I previously argued in this post discussing the Green Deal, achieving net zero emissions in the EU by 2050 will cause significant economic dislocation. It will also require significant additional investment in coming decades. Even if much of the necessary investment must be undertaken by the private sector (stimulated and incentivised by a rising price on carbon), the EU budget can contribute directly to this investment through its own spending priorities as well as leveraging additional private investment.

In its plans to mobilise €1 trillion over the next ten years to help to finance the green transition, over 40% of the EU budget contribution will consist of CAP spending. To make this happen, the Commission proposes that 40% of CAP expenditure should be climate-relevant. To assess climate relevance, the Commission applies climate markers to specific items of CAP expenditure. The previous analysis shows that the climate markers the Commission proposes to use will significantly overstate the climate relevance of CAP expenditure, risking a major loss of credibility in the financing of the European Green Deal as this massaging of the figures becomes more widely known.

There are a number of ways in which the Commission’s proposal must be improved, some of which are more radical and thus more difficult to implement in the short-run (see also the suggestions in this report by Ricardo Energy & Environment, IEEP and others on Climate mainstreaming in the EU Budget: Preparing for the next MFF prepared for DG CLIMA in 2017).

- Where a measure is expected to have a climate impact, ideally, the expected impact should be specified and, where possible, quantified. Quantification is more relevant to measures that address mitigation rather than adaptation, though even here it can be difficult ex ante to assess likely mitigation impacts and even more difficult to measure whether these impacts have been achieved ex post. Nonetheless, Member States in preparing their own climate action plans will need to show how they intend to achieve the mitigation targets set out in their National Energy and Climate Plans. Quantifying the mitigation effect of individual CAP measures will be an important element in this.

- Even if the Commission’s climate weightings (0%, 40% and 100%) are maintained, these should be applied at the most disaggregated level of interventions possible. Whether all measures intended to address specific objectives (d), (e) and (f) in Article 6 of the draft Strategic Plans Regulation actually warrant a climate marker of 100% should be examined.

- The Commission has failed to provide any justification why the enhanced conditionality attached to the basic income support and redistributive payments would warrant a 40% climate marker. There is the purely formalistic argument that, because some of the conditions may help to lower emissions or improve resilience, a marker greater than 0% is warranted and the next step is 40%. If the Commission really wants to incentivise the vital next steps in the green transition in agriculture, the metrics are important and should reflect the real impact on the ground. It is hard to understand why payments to a maize farmer growing maize silage for animal feed using conventional chemicals and fertilisers are assumed to contribute to climate action with a coefficient of 40%.

- One possible approach would be to try to quantify the climate impacts of the enhanced conditionality requirements for a sample of sites covering different farming systems, soil types and climate zones across the EU. For mitigation reductions, these could be valued at a specific cost of carbon (say, €35/tonne which might be increased over time in line with changes in the cost of allowances in the Emissions Trading Scheme). A more subjective approach would need to be taken to quantify the likely benefits of greater climate resilience. Measures that are part of legal requirements should be ignored as only actions that are incentivised by CAP payments are relevant. Aggregating up the values for the EU as a whole would give a total value of climate action that could then be compared to direct payments expenditure to derive an initial proportion.

- Some discounting should be introduced to reflect the fact that the climate benefits of direct payments (as well as many agri-environment-climate measures) are only obtained in the year the payments are made and will require a continuing stream of payments year after year to be sustained. This is very different to a similar investment in, say, converting a coal-fired power plant to run on natural gas or biomass where the once-off investment leads to a permanent reduction in emissions. The Sustainable Europe Investment Plan calls for the mobilisation of €1 trillion in investments, but many (most?) of the changes incentivised by the CAP are not investments but (temporary) changes in management practices that might easily be reversed if the payments were to disappear.

- Finally, consideration should be given in climate tracking to net off the impact of CAP payments that lead to negative climate impacts, whether these be coupled livestock payments or investment supports for unsustainable irrigation practices.

Addendum 29 Jan 2020. This quotation from a policy contribution by Grégory Claeys, Simone Tagliapietra and Georg Zachmann for the Bruegel think tank last year makes similar points.

….increasing the target [the share of climate-relevant expenditure in the EU budget] goes in the right direction, but for the EU budget to be significant in filling the green investment gap, it is also crucial to review how EU expenditures are accounted for as contributing to the fight against climate change. The current methodology tends to overestimate substantially the contribution of the EU budget, in particular of agricultural funds (European Court of Auditors, 2016). Each expenditure item is given a climate coefficient of 0 percent, 40 percent or 100 percent depending on its contribution to climate change mitigation or adaptation. This method has the advantage of being simple and pragmatic, but can be highly misleading: for instance, expenditure that leads to an increase in emissions does not have a negative coefficient for negative impact. A more demanding but much more accurate methodology that would try to estimate carbon content of each action would help make the EU budget genuinely greener.

Update 14 February 2020: Those interested in this topic will also find this briefing Keeping track of climate delivery in the CAP published on 12 February 2020 by a team of authors from the Institute for European Environmental Policy of interest.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Picture credit: andreas160578 (pixabay.com) under a Creative Commons licence

Dear Alan,

You have been very kind with the Commission by remaining in the accountability space, and not mentioning the (almost inexistent) impacts on the ground of such expenditure. Indeed, in a period where supposedly over 25% of the CAP payments were considered “climate action”, emissions from agriculture started to grow again in the EU. (see for instance: https://agridata.ec.europa.eu/extensions/DashboardIndicators/Climate.html).

The evaluation made by independent consultants of the climate impact of the CAP also shows that this policy is hardly triggering any changes in the ground towards more climate-friendly farming practices. See full report here: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/evaluation/market-and-income-reports/2019/cap-and-climate-evaluation-report_en.pdf

Shouldn’t this evidence make it obvious for policy makers that in the absence of more desaggregation and justification, as you suggest, the percentages in the climate accountability article should be drastically reduced?

@Jabier, very relevant comment. Indeed, in my post I focused entirely on the accounting rules (so-called ‘climate markers’) but equally important is evidence of what works on the ground. Thanks for highlighting the evaluation report which will be worth a separate post in itself.