From tomorrow, 1st January 2012, life for the EU’s laying hens becomes a little better when EU Council Directive 1999/74/EC on the Welfare of Laying Hens comes into force. Under the Directive the use of conventional cages (commonly referred to as ‘battery cages’) for laying hens will be prohibited in the EU as will the marketing of eggs from hens housed in such cages.

The ban on battery cages follows the EU-wide ban on veal crates for calves which came into force in 2007, and will be followed next year by a ban on sow stalls and tethers which comes into force across the EU on 1 January 2013. These are the first pieces of legislation to phase out methods of production due to animal welfare concerns.

The use of cages

The Directive initially required a minimum space requirement for battery hens in conventional battery cages per bird of 550 cm2, about the size of a sheet of A4 paper, from 1 January 2003. It disallowed construction of new conventional battery cages after that date and their use is now illegal from tomorrow. Minimum requirements were also set down for enriched cages which must have a minimum of 750 cm2 per bird as well as a nest, perches and a scratching area.

Enriched cages continue to be allowed for egg production although individual member states have gone further. In Germany, conventional cages have been banned since 1 January 2010 and enriched cages will also be banned from tomorrow (so production will be entirely in non-cage systems). The use of conventional cages is also already banned in Austria, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Animal welfare campaigners, however, believe that battery egg hens still face hell as the enriched cages are phased in and want the whole of the EU to follow the German example.

Uneven compliance

However, despite the long lead-in time, figures given to the November Agricultural Council by DG SANCO suggested that around 50 million laying hens (from a flock of around 290m, or 18% of total) are still kept in conventional battery cages. In theory, it will be illegal to market these eggs but an immediate ban would lead to a sudden shortage in particular markets and is thus unlikely to happen.

Mr Dalli, the Commissioner for Health and Consumer Policy whose office DG SANCO has the responsibility for animal welfare, has promised to open infraction proceedings against eleven member states which have dragged their heels on this issue – the countries include Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Portugal and Romania.

Member states whose egg producers have complied with the new legislation and invested in the new cages are concerned that sales of their eggs may be undermined by sales of cheaper eggs from countries whose producers are not yet fully compliant.

Evidence given to a UK House of Commons committee investigating the issue earlier this year suggested that, in addition to the capital costs, the production costs for enriched cages are estimated to be 8% higher compared to a conventional cage. But fears of a flood of non-compliant eggs into compliant markets may be misplaced.

DG AGRI figures (see Figure 1) show that much wider differences in egg prices currently exist on the EU market, ranging from a low of €82/100 kg in the Netherlands to €121/100 kg in Germany and much higher prices of €170/100 kg in Sweden and €173/100 kg in Denmark (these prices are for Class A eggs from caged hens, average of L and M sizes, and thus are not affected by different market shares for caged, free range and organic eggs in different markets).

Trade in eggs

Trade in eggs takes place mainly between neighbouring countries, and mainly in the form of shell eggs, although the share of trade in the form of egg products, such as powdered or liquid egg, mainly used in the catering trade and food processing is growing. The egg industry argues that higher standards lead to a competitive disadvantage in egg production, but to date there is limited evidence that this has occurred.

Figure 2 shows the recent trends in global shell egg trade which now amounts to around $3 billion annually, with the EU-27 accounting for around $2 billion of this. Most of this is intra-EU trade, with little trade taking place with third countries. It is clear that, despite the higher standards introduced for conventional battery cages from 2003, the EU has not lost ground in trade in shell eggs, and in fact its net export surplus increased. The most recent large-scale avian flu outbreak occurred in the middle of the period, in 2005 and 2006, but it appears to have had no major effect on trade. Trade in egg products is much lower, but the story is the same – the EU remains a small net exporter.

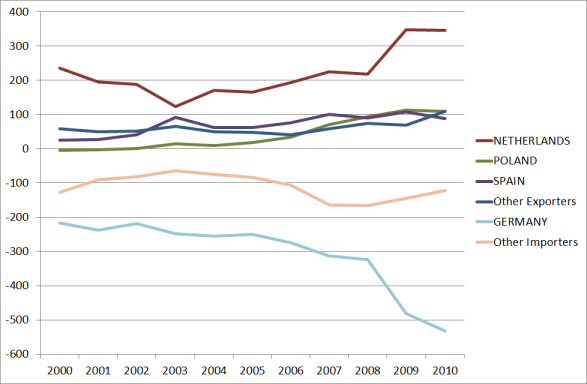

More interesting are the changes taking place in intra-EU trade, shown in Figure 3. Germany is by far the largest import market, and its net imports have been steadily increasing. Most of its imports are sourced from the Netherlands, the largest net exporter, but net exports have also been growing from Poland and some of the other new member states (who account for most of the growth in the ‘other exporter’ category).

Germany bans the use also of enriched cages from tomorrow. It still permits the use of ‘family’ cages (also called ‘small aviaries) which have more space than enriched cages, but apparently consumer resistance has meant that such eggs have not gained a foothold in the market. Egg industry sources claimed some time ago that the ban on enriched cages will lead to a further drop in egg production in Germany, leading to increased German imports and that, from 2012 on, the EU will become a net importing region for shell eggs.

We have seen that, to date, higher welfare standards for laying hens do not appear to have adversely affected the EU’s trade balance in eggs (of course, in the absence of these standards the EU’s net export surplus in eggs and egg products might have been greater). There is clearly a pain threshold as welfare standards are raised ever higher, but there still seems to be scope for the EU to maintain its competitive position.

The large differentials in egg prices between member states suggest that other factors, including flock size (which affects economies of scale), feed costs and labour costs, have a more significant impact on total egg production costs. And in many countries especially in northern Europe the consumer preference for eggs from non-caged birds has meant many retailers are adapting their supply chains to meet this preference (although egg products are by and large untraceable and thus more vulnerable to substitution on cost grounds).

Whatever about the medium-term future for the EU egg industry, the more immediate question is what will happen to the eggs from those 50 million hens in conventional battery cages from tomorrow?

We also take this opportunity to wish our readers a very happy New Year.

Picture on home page copyright FarmSanctuary.org and used by permission under a Creative Commons licence.

This post is written by Alan Matthews

Excellent news, I read that all the surplus animals will be slaughtered.

As usual, welfare of some comes at the expense of others:-)

It is absolutely right that the livestock we have in our care enjoy appropriate welfare and environmental conditions while they produce our food. We certainly could not live without them. The caged hen is a case in point and the consumer must be appropriately informed via correct labelling of who is doing what.

What is currently alarming is the condition of dairy cows housed year round 24/7. These dairy animals are fed for their milk and now increasingly for their slurry. What is not happening is that they are fed and cared for in relation to their own health and condition.

We are now seeing emaciated cows pushed to their limits both milking providing very technical protein contents of milk for different markets and at the same time producing a higher percentage than normal dry matter in slurry for the anaerobic digestor.

These herds are hidden. The cows at grass are a very different animal and this is apparent with the naked eye. The cows inside are both filthy and malnourished also apparent from simple observation. The RSPCA has a method of scoring animal condition but not if they are hidden away.

We need to know where the 24/7 year round housed dairy cattle are. Where are the statistics on this?