I have argued before on this blog that the EU’s policy during the food price spike of 2007-08 in lowering applied tariffs on staple foods may have helped to mitigate the impact of higher food and feed prices on livestock producers and, to some extent, on consumers, but at the expense of exacerbating the global price increases facing other countries, including developing countries.

The EU’s policy of varying applied tariffs within its bound rates contributed to destabilising world market prices just as did the export restrictions applied by other countries, and undermines its moral authority, in the G20 and elsewhere, in seeking strengthened WTO disciplines on export restrictions as a way to enhance global food security.

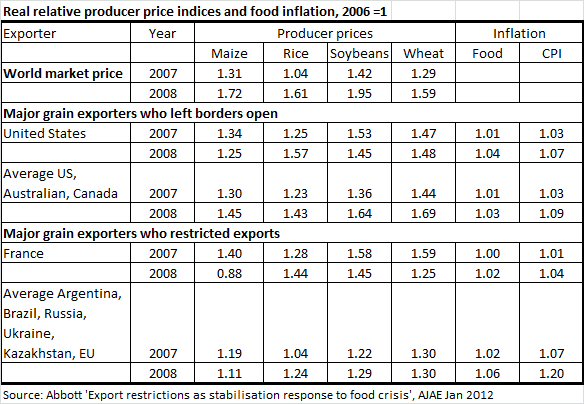

In a paper [requires library access] published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics in January this year, Philip Abbott of Purdue University provides some quantitative evidence of this effect. His methodology is straightforward. He compares the evolution of producer prices for staple commodities with the trend in retail food prices over the 2006-2008 period, distinguishing between major grain exporters which left borders open and major grain exporters which restricted exports. As a major grain exporter, France is chosen as the country to represent the EU in this latter category, bearing in mind that the EU’s policy response was to eliminate import tariffs on wheat and maize rather than to impose export restrictions as such.

Contrasting responses are seen by the United States, Canada and Australia, which avoided trade restrictions, versus Argentina, Brazil, the European Union, Russia and most Asian rice exporters, which taxed or banned exports or facilitated imports to limit impacts on consumers, agribusiness or livestock producers. The case of the Asian rice exporters is less relevant in highlighting the consequences of the EU response and is not considered further here.

In the U.S. relative real producer prices increased about 25% in 2008 from 2006 for corn, 57% for rice, 45% for soybeans and 48% for wheat. These are only somewhat lower than real world price increases, as the U.S. left its border open and world prices are denominated in dollars, and Abbott argues is as good a standard as world prices to gauge other countries’ behaviour toward farmers. Despite this increase in staple food prices, food and consumer price inflation (CPI) in the US between 2006 and 2008 remained very low, at 4% and 7% respectively (the food inflation rate is in real terms, expressed relative to the increase in the CPI).

The averages for the three major grain exporters which left borders open show similar, if higher, farmgate price increases, at about 45% for corn and rice and 65% for wheat and soybeans. Excess (real) food price inflation averaged just 3% over the two years in these exporters.

Those major exporters which restricted exports realized lower farmgate price increases, at 11% for corn and 25–30% for the other agricultural commodities. Despite these stabilisation efforts, relative food prices increased by 6% (and by 11% for the rice exporters not shown).

The case of France, representing the EU, is striking. Producer wheat prices rose by less than half compared to the ‘open’ grain exporters and maize prices were actually lower in 2008 compared to 2006. Relative food prices increased by only 2% between 2006 and 2008. Part of the reason why EU producer prices increased less than US prices was because the euro strengthened against the dollar between 2006 and 2008 (from $1.26 to $1.47) which explains the lower producer price increases for rice and soybeans, but the even stronger effects on wheat and maize prices also reflects the impacts of lower tariffs.

Abbott uses these data to tell a story about why some countries intervened to lower producer prices while other countries did not. Two key determinants are differences in diet composition and differences in the length of food supply chains. Consumers in countries where food takes a higher share of consumer expenditure, where diets contain lower shares of meat and processed foods, and where margins between retail and producer prices are smaller, are more vulnerable to higher staple food prices and thus more likely to intervene.

The ‘open’ grain exporters where farmgate prices followed world market prices are all high income countries where livestock feeders or food processing and distribution margins absorbed much of the impact before it reached consumers.

Against this background, the EU’s behaviour is even more of an outlier and harder to explain let alone justify. For the same structural reasons as in the US, Australia and Canada, consumers are relatively insulated from sharp price spikes even without a stabilising policy response to lower import tariffs.

The political economy explanation for the EU intervention was to protect its livestock producers by redistributing some of the windfall gains earned by grain farmers. The unintended, if predictable, outcome of this policy was to shift the burden of adjusting to higher prices on to the shoulders of more vulnerable consumers in developing countries.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit Miss Steel