One of the innovations in rural development programming for the next multi-annual period is that there is meant to be much greater integration between EAFRD spending and spending through the other structural and investment funds. Trying to achieve this greater integration has been, and is, a fraught and time-consuming process, with implications for when member state and regional rural development programmes (RDPs) will get the green light to proceed.

I described how this process is intended to work in an earlier post. In a first step, the Commission has drawn up a Community Strategic Framework (CSF) which is intended to facilitate the sectoral and territorial coordination of union intervention under the CSF funds and with other relevant Union policies and instruments. The CSF Funds include the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the European Social Fund (ESF), the Cohesion Fund (CF), the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF).

The Community Strategic Framework

The CSF establishes the key areas of support, territorial challenges to be addressed, policy objectives, priority areas for cooperation activities, coordination mechanisms and mechanisms for coherence and consistency with the economic policies of Member States and the Union.

The guidelines for the CSF were attached to the CSF Funds’ Common Provisions Regulation which sets out a common set of basic rules for the operation of the different Funds. These provisions concern the general principles of support such as partnership, multi-level governance, equality between men and women, sustainability and compliance with applicable EU and national law. The Commission published its first proposal for the Common Provisions Regulation in October 2011.

The proposal contained the common elements of strategic planning and programming, including a list of joint thematic objectives derived from the Europe 2020 Strategy, provisions on the Common Strategic Framework at Union level and on the Partnership Agreements (then called Partnership Contracts) to be concluded with each member state. The Commission presented its draft CSF in March 2012. Strong alignment with policy priorities of the Europe 2020 agenda, macroeconomic and ex-ante conditionality, thematic concentration and performance incentives are expected to result in more effective spending.

The Common Provisions Regulation initially foresaw that the CSF would be adopted by the Commission as a delegated act separate from the regulation itself. Both the Council and Parliament’s Committee on Regional Policy signalled that they wished to see the CSF adopted as an annex to the regulation and not as a delegated act. To facilitate compromise, the Commission presented an amended Common Provisions legislative proposal in September 2012 which included the CSF as a new Annex 1.

The final text of the regulation, including the CSF, was eventually agreed between the Council and the Parliament a year later in November 2013 and published in the Official Journal on 20 December last. This is an important date as it starts the clock ticking on the subsequent stages of the programming process.

Partnership Agreements

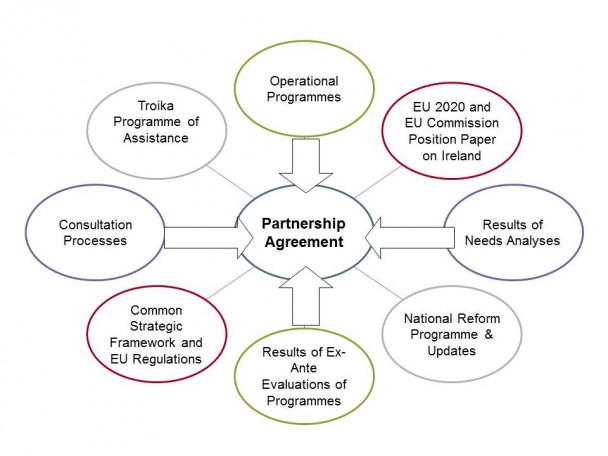

On the basis of the CSF, each Member State must prepare, in cooperation with local partners, and in dialogue with the Commission, a Partnership Agreement. Partnership Agreements outline the allocation of national and EU resources between programmes and priority areas, conditionalities and targets. Each Partnership Agreement should be informed by a number of policy instruments at national and European level. At European level the main instruments are the EU’s ten-year growth strategy (EU2020) and the Common Strategic Framework, which translates the objectives and targets of the Union priorities of smart, sustainable and inclusive growth into key actions for each operational programme. As an example, the national and EU instruments informing the Irish Partnership Agreement are shown in the diagram.

At the moment, member states are consulting with local partners and with the Commission on the direction and content of their individual Partnership Agreements. In Ireland, the draft Partnership Agreement was circulated for comment in November.

The Common Provisions Regulation provides that each member state must submit its Partnership Agreement to the Commission within 4 months from the entry into force of the Regulation (this was 20 December 2013 as noted previously). The Commission then has 3 months from the date of submission of the Partnership Agreement to make observations and must adopt the Agreement no later than 4 months from its submission, provided that the member state has adequately taken into account its observations. This means that as a general rule, Partnership Agreements should be adopted by end of August 2014 at the latest.

Operational and rural development programmes

Operational Programmes and rural development programmes (RDPs) draw on these strategic documents and translate them into specific investment priorities with measurable targets. The Common Provisions Regulation provides that these programmes should be submitted by member states at the latest 3 months following the submission of the Partnership Agreement. The Commission then has another 3 months from the date of submission to make observations and must adopt the programme no later than 6 months from the date of its submission, provided that the member state has adequately taken into account the Commission observations.

This means that RDPs should be adopted by end of January 2015 at the latest. Member states will hope, of course, that the approval of the Partnership Agreements and subsequently the operational and rural development programmes will not take so long. There has already been a lot of contact between the Commission and member state officials in the course of 2013 both on the content of the Partnership Agreements and on the design of the programmes.

However, some time is needed to follow the processes required. In the case of rural development programmes, they must be accompanied by an an ex-ante evaluation by an independent contractor, undergo a public consultation, and include a SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) a needs assessment, a strategic environmental assessment (SEA) and an appropriate assessment (AA). While the first RDPs may be cleared by the early summer, there could still be some still awaiting approval by the end of this year.

The partnership process

In the co-decision process between the Council and the Parliament on the Common Provisions Regulation the partnership principle was strengthened. The provisions on Partnership Agreements were amended so as to give local and regional authorities and partners representing civil society the right of further scrutiny regarding planning and implementation.

It was also agreed that a code of conduct would be established to set out a framework within which Member States would support the implementation of partnership. Experience shows that member states implement the partnership principle in very different ways, depending on national institutional set-ups and traditions of stakeholder involvement. The effectiveness of partnership also depends on partners’ capacity to contribute substantively to the process.

This delegated regulation on the European code of conduct on partnership lays down the conditions for involvement of partners in the preparation and implementation of 2014-2020 partnership agreements and programmes and was adopted by the Commission on 7 January last.

The code of conduct sets out objectives and criteria to ensure that member states implement the partnership principle as envisaged in the Common Provisions Regulation. Member states are required to:

• ensure transparency in the selection of partners representing regional, local and other public authorities, social and economic partners and bodies representing the civil society, to be appointed as full members in the monitoring committees of the programmes;

• provide partners with adequate information and sufficient time as a prerequisite for a proper consultation process;

• ensure that partners must be effectively involved in all phases of the process, i.e. from the preparation and throughout the implementation, including monitoring and evaluation, of all programmes;

• support the capacity building of the partners for improving their competences and skills in view of their active involvement in the process

The delegated regulation on the code of conduct is accompanied by a Staff Working Document gathering examples of best practices as regards implementation of the partnership principle in the European Structural and Investment Funds’ programmes. It enters into force after a further two-month period during which the European Parliament and the Council can express objections.This new instrument should be particularly useful in countries where the tradition of stakeholder involvement is less embedded.

Photo credit: © Copyright John Chroston and licensed for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence.

Europe's common agricultural policy is broken – let's fix it!