In its most recent Farm Bill in 2014, the US eliminated its decoupled direct payments, in part because it was hard to justify making income support payments to farmers at a time when farm incomes were booming due to favourable prices. Instead, it substituted a new set of counter-cyclical payments as part of the US farm safety net. At the same time, it expanded the scope of its federal crop insurance programmes by introducing a new programme to cover ‘shallow losses’ not normally covered by these programmes.

These US developments have led some in Europe to argue that the CAP should move in the same direction. Direct payments should be reduced and the money used instead to support insurance products for farmers or to fund counter-cyclical payments. This blog post does not discuss the merits of these proposals (for discussion, see this report prepared for the European Parliament’s COMAGRI). The US programmes are not widely known. In this post, I summarise the main features of what can be very complex programmes at the farm and operational level.

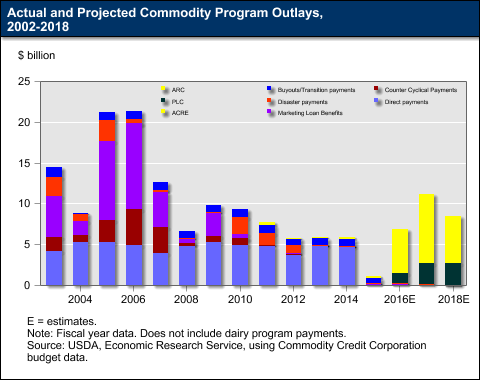

The US farm safety net has three pillars: federal crop insurance, farm commodity programmes, and disaster assistance. Under the 2014 Farm Bill, the projected annual cost of these three pillars is $8.8 billion, $4.2 billion and $0.5 billion, respectively (figures from Shields, 2015). Actual costs will differ because these are counter-cyclical programmes which cost more in bad years for farming than in good years.

Federal crop insurance

Federal crop insurance is now the centrepiece of the US farm safety net, having overtaken commodity programmes some years ago. It makes available subsidised crop insurance to producers who purchase a policy to protect against losses in yield, crop revenue, or whole farm revenue (including livestock producers to a limited extent). Federal crop insurance is managed by the US Department of Agriculture’s Risk Management Agency.

Yield policies protect against agricultural production losses due to unavoidable natural causes such as drought, flooding, hail, wind, hurricane, tornado, lightning, and insects. Revenue policies protect against revenue losses resulting from changes in prices and/or yields. Livestock policies protect either against a loss in gross margin (market value less feed costs) or against price declines but are much less utilised.

The producer selects a coverage level – for example, for revenue policies, coverage level choices range from 50 to 85% of market revenue. The producer absorbs the initial loss through the deductible. For example, a coverage level of 70% has a 30% deductible (for a total equal to 100% of the expected value prior to planting the crop). Policies pay a loss on an individual basis and an indemnity is triggered as a result of an individual farm loss in yield or revenue which must be determined by an insurance company loss adjuster.

Producers pay a portion of the premium which increases as the level of coverage rises. The federal government pays the rest of the premium (62%, on average, in 2014) and covers the cost to insurance companies of selling and servicing the policies. The government also absorbs some of the losses of insurance companies in years when payouts to farmers are particularly high.

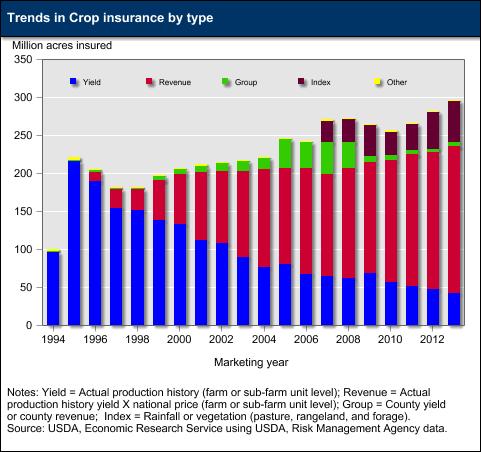

Around 1.2 million policies are purchased annually, providing nearly US$110 billion in insurance coverage. More than 120 commodities are insurable. For major crops, more than three-quarters of the US planted area is insured under this programme. Over time, revenue insurance has displaced yield insurance as the most popular type of insurance policy (see following figure).

Supplemental Cover insurance

The 2014 Farm Act authorised the Supplementary Coverage Option (SCO) to help producers to cover the deductible loss on farm crop insurance policies (hence the description of this scheme as a ‘shallow loss’ programme). Farmers can now purchase a second policy on the same acreage, with the amount of coverage related to the liability level and approved yield for the underlying policy.

For example, for a revenue insurance policy, the SCO option begins to pay when county average revenue falls below 86% of its expected level.

The full amount of the SCO coverage is paid out when the county average revenue falls to the coverage level of the underlying policy (assume this is 70%). In this case, this supplementary option provides protection for up to 16% of the value of the crop. The premium for this policy is covered by a 65% subsidy.

Unlike the underlying policy which is triggered where there is an individual farm loss in either yield or revenue, the SCO is triggered when there is a county-level loss in yield or revenue (not an individual farm loss). So it is possible for a farmer to receive an SCO payment even where he or she has not made a claim under the underlying policy, and vice versa. Producers who elect to participate in the Agriculture Risk Coverage programme are not eligible to purchase SCO coverage.

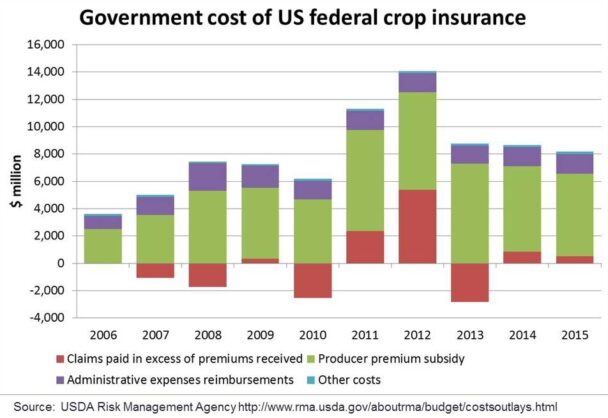

The annual cost to the government of US federal crop insurance in recent years and how this is made up is shown in the following figure.

Farm commodity programmes

Minimum price supports

Farm commodity programmes provide minimum price support to producers of a narrower range of crops (called programme crops) through a system of non-recourse marketing assistance loans and loan deficiency payments. Loan rates, or minimum prices, are set for each programme crop.

The system works as follows. Farmers take out a loan with the USDA Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) to finance their planted crops, with those crops as collateral. They have two options to repay this loan. If the market price for the crop is above the loan rate, the producer repays the loan and keeps the balance. If the market price falls below the loan rate, they can forfeit the crop to the CCC as repayment of the loan (hence the term “non-recourse loan”). Effectively, this is equivalent to selling the crop at a price equal to the loan rate.

However, to avoid the build-up of government stocks, the CCC offers producers the choice to repay the loan at a lower rate effectively equal to the going market price. In this case, the producer has received a marketing loan gain equal to the amount by which the applicable loan rate exceeds the loan repayment rate.

Loan deficiency payments (which are basically equal to marketing loan gains) are available to eligible producers who choose not to take out a crop loan. Loan rates were increased significantly in the 2014 Farm Bill.

For dairy producers, minimum prices are assured through a system of Milk Marketing Orders which, for specific geographical regions, require milk processors to pay a minimum blended price reflecting the product composition of output in that region.

Counter-cyclical payments

Counter-cyclical payments now play a much more important role than minimum price support. The 2014 US farm bill introduced two types of counter-cyclical payments for crop producers which replaced an earlier programme. Producers have a choice between a Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and an Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) programme, depending on their preference for protection against a decline in either (a) crop prices or (b) crop revenue.

Mahé and Bureau in their European Parliament report describe these programmes as follows:

Under the PLC, participating producers receive a payment when national season average farm prices fall below fixed reference prices. Under the ARC, payments make up the difference between a county revenue guarantee (based on five-year average crop prices or statutory minimums) and actual crop revenue.

Producers can choose PLC or the county version of ARC on a crop-by-crop and farm-by-farm basis, or they can choose an individual version of ARC for all the crops on a farm. ARC payments are capped at 10% of crop benchmark per acre revenue, while PLC payments can cover the difference between the crop reference price and the loan rate.

Unlike federal crop insurance, producers do not pay to participate in these programs. Payment recipients can plant any combination of crops on their land, but conservation rules must be followed. Maximum payment limitations apply.

Dairy Margin Protection Programme

This commodity support programme makes payments to participating milk producers when the national margin (average farm price of milk minus an average feed cost ration) falls below a producer-selected margin. Producers elect how much of their historic production will be covered and at what margin, between $4 and $8 per hundredweight.

Enrolling the milk margin at the lowest level only requires payment of a nominal administrative fee. Elections above $4 per hundredweight require payment of an additional premium above the nominal base fee. To date, only dairy producers who enrolled at the $6 through $8 margin trigger coverage level have received payments.

The annual and projected costs of US farm commodity support programmes (including disaster programmes but not including the government cost of farm insurance) is shown in the following figure.

Disaster assistance

Farm commodities not well covered by farm insurance programmes are eligible for agricultural disaster assistance. The 2014 farm bill permanently authorised three disaster programs for livestock and one for orchards and vineyards. The livestock programmes, for example, compensate farmers for livestock deaths above average due to adverse weather, or farmers who have suffered grazing losses due to drought, or compensate losses due to adverse weather, disease, or feed or water shortages. Low-interest emergency loans can be authorised when a natural disaster is declared, while the US Department of Agriculture has the discretion to make ad hoc payments to producers in case of extraordinary losses. Up to 30% of US customs receipts can be used to fund a crisis reserve for these purposes.

Conclusions

The US farm safety net has evolved very differently to farm support in the EU, particularly after the 2014 Farm Bill. The 2008 CAP Health Check did permit member states to use up to 10% of their direct payment ceilings to support crop and livestock insurances, but there was little interest in this facility.

The 2013 CAP reform moved support for insurance products into the revamped rural development regulation. It also extended the toolbox to include support for mutual funds which set up income stabilisation insurance for their members.

Again, the uptake of this measure in the 2014-2020 rural development programmes submitted by member states was very limited. The Commission in its recent proposal in the so-called Omnibus Regulation to revise the CAP basic acts has suggested that the rules on operating conditions for these income stabilisation funds could be relaxed in an effort to stimulate their uptake.

One of the questions for the discussion on the next CAP reform which is now beginning is whether it would make sense to move further in this direction. It seems to me the jury is still out on this question.

Most people insure against the very occasional risk of an emergency and are willing to pay a small premium to cover this eventuality. Insuring farmers against market price risk would be a challenge for insurance providers.

Market price variability could mean much more frequent pay-outs and thus correspondingly much larger premiums. Administrative costs could be high. The cost efficiency of the US insurance programme is poor. It has been estimated that every time an American farmer receives one net dollar through the insurance system, it costs two dollars to the American taxpayer.

Unless insurance products are very heavily subsidised as in the US, most farmers would probably continue to prefer to self-insure against market risks, through building up savings in good years and drawing these down in bad years. Such savings behaviour can be encouraged through provisions in national tax systems which permit the spreading of income flows across years.

Nonetheless, there is growing interest across Europe in the provision of revenue and income-linked insurance products to farmers. The use of index-linked insurance may hold promise in reducing administrative costs, although at the expense of increasing basis risk for farmers (this is the difference between what a farmer actually experiences on his or her own farm and what the index used to predict this outcome says is happening).

It makes sense for the CAP to continue to encourage this experimentation at member state level. How best to do this, and what the appropriate level of public support for such initiatives should be, we leave for another post.

Sources of information

I used the following sources of information on the US farm safety net among others in preparing this post.

USDA Risk Management Agency home page

USDA Crop and Livestock Insurance home page

USDA Farm Services Agency home page

USDA Agricultural Act of 2014: Highlights and Implications

Shields, D., 2015. Farm safety net programs: background and issues

Mahé, L-P. and Bureau, J.C., 2016. The future of market measures and risk management schemes, Chapter 1.3 European Parliament.

This post was written by Alan Matthews. Updated 4 November 2016 to reflect use made of material in the Mahé and Bureau report and to revise description of marketing assistance loans.

Photo credit: Iowa dairy farm, US Department of Agriculture Flickr used under CC licence

What appears to be missing if from the debate is the philosophical objective. The USA system is not a beacon.

Income volatility from multiple causes is relatively cheap to manage through multi year tax averaging. Profit averaging is farm specific and does not relate to variability in any single component of profit. This allows adjustment to the trend rather than knee jerk reaction. It also reduces the investment that can be justified in to additional measures which consequently providing a smaller marginal gain.

However, it provides insufficient help to manage the truly abnormal event such as disease or flooding. There are already insurance policies that cover these elements providing cover at generally modest cost. A compulsory scheme EU wide would lower the cost per farmer quite significantly but there is also merit in self insuring. Should those living on a mountain contribute to covering others’ flood risk? In the UK hail is a risk to oilseed rape and can wipe out 80% of the crop yield but relatively few farmers insure recognising that the damage is unlikely to lead to collapse of the business and that on average the cost is greater than the return – as it has to be to cover the administration of an insurance scheme.

In my experience the damage from volatility is greatest for those sectors that are not used to the volatility of market prices (e.g. in their halcyon youth were protected by high intervention/export refunds or in the UK milk sector by a monopoly buyer). In fact price stability has only ever occurred for a short period of time. Annual UK wheat prices (once corrected for inflation) shows a static level of volatility for nearly 1000 years.

The philosophical element centres on 1) what risks should government take responsibility for. Maybe just those that it has responsibility for such as trade sanctions? 2) the level of resource that can be legitimately transferred from other parts of the economy.While food is vital for most people it is not the ability to find food but the ability to pay for it that causes suffering.

Having tried not to be political I do sometimes feel that there is a desire amongst politicians to introduce more complex schemes than absolutely necessary.

A very interesting article which I enjoyed reading. Studies in the United States about American agricultural policy have revealed that a significant part of the subsidies go to wealthy organizations and persons rather than the poorer farmer. On the web site, http://www.openthebooks.com which displays United States federal, state and local government expenditure there is an analysis of all such expenditure concerning the agricultural sector and other sectors too. This openness about American governmental financial support for the agricultural sector contracts greatly with that of the European Union where since 2010 information about the private recipiants of Common Agricultural Policy funds is not allowed to be displayed on the internet following a European Court of Justice ruling. The case was brought by three German farms.

One study revealed that many of the recipiants of the American subsidies were resident in the better parts of New York and Chicago. I believe, that about 30 % of CAP subsidies still go to the European landed nobility.

In the UK the largest recipients are certainly not the aristocracy. Other farms are bigger and traditional landed estates are largely let. Larger businesses obtain more subsidy and employ more people. Employees are the most threatened part of the system, not farmers who have capital (land, stock, machinery).

As it happens some of the most environmentally friendly farmers in the UK are the larger ones – although there are good examples of all sizes. In practice smaller land owners often receive most of their income off farm – but large, small or aristocratic the contribution is the same.

There is nothing inappropriate about arguing for the removal of subsidy. There is a lot wrong with discrimination on the grounds of age, race, sex or being a member of the aristocracy.