The U.S. has agreed on a $2 trillion stimulus package, the largest economic stimulus in its history, in response to the economic impacts of Covid-19. U.S. farm groups lobbied hard to be included in the package, and $23.5 billion was included in the final package for farm aid. This farm aid comes on top of the two trade aid packages of $12 billion and $16 billion introduced by the Trump Administration in 2018 and 2019, respectively, to provide relief to commodity producers hurt by the retaliatory tariffs introduced by various countries in response to tariffs on their exports to the U.S. introduced by President Trump.

Assuming no change in market prices and other farm income in 2020 compared to the February 2020 USDA farm income forecast, if all of this emergency aid were paid out in 2020, then 40% of U.S. farm income in 2020 will derive from government payments. While not all of the emergency aid may be paid out in calendar year 2020, it is also likely that counter-cyclical payments will increase and other farm income will also fall compared to the February 2020 forecast in response to falling export and home demand. This means the projection that around 40% of all U.S. farm income this year will derive from government support is probably not far off the mark. This would be unprecedented in recent U.S. history, but would still mean that the share of government support in the U.S. is below the level in the EU.

The CARES Act

President Trump signed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, also known as the CARES Act, into law on 30 March 2020. The original bill introduced by the Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell would have provided around $1 trillion in aid. By the time bipartisan negotiations had concluded, the amount of aid provided had increased to $2 trillion, around 10% of US GDP. The act is much larger than the $831 billion stimulus act passed in 2009 as part of the response to the Great Recession.

These proposals follow an initial $8.3 billion measure passed in early March to boost Covid-19-related emergency funding, as well as the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) that provided funding for free coronavirus testing (though treatment still came at a cost), 14-day paid leave for American workers affected by the pandemic, and increased funding for food stamps.

The main provisions of the CARES act have been widely reported though there are different estimates for some of the amounts in the package (see also here). The most innovative feature is around $250 billion in ‘helicopter money’ to American families below a specified income threshold who will receive checks of up to $1,200 per person (plus $500 for children under 16) through the tax system (it is estimated around 94% of Americans will be eligible). A further $250 billion will go to bolster unemployment insurance. There is $350 billion in loans for small businesses that may be forgiven if firms use them to keep workers on payroll. $500 billion in aid is made available for hard-hit large corporations and $50 billion for airlines. Hospitals get $130 billion in aid to cover the cost of treating uninsured workers, while there is $340 billion to help state and local governments cover budgetary shortfalls as tax income plummets.

Farm aid in the CARES Act

As late as February this year, in the wake of the partial trade deal between the U.S. and China under which China committed to increase purchases of U.S. agricultural exports, the Secretary for Agriculture Sonny Perdue was advising farmers not to count on receiving additional payments for trade disruption in 2020. He envisaged the end of the Market Facilitation Program that had provided farm income support in the two trade aid packages in 2018 and 2019.

Mind you, the very next day President Trump tweeted that if farmers needed more aid while waiting for the terms of various trade deals to kick in, that money would be made available from the tariff revenue generated on imports into the U.S.. As it has turned out, the stimulus for additional aid has not been trade on this occasion, but the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic.

There are two main elements in the farm aid package in the CARES Act. The first is $9.5 billion in emergency aid that is made available to the Secretary for Agriculture to provide “support for agricultural producers impacted by coronavirus, including producers of specialty crops, producers that supply local food systems, including farmers markets, restaurants, and schools, and livestock producers, including dairy producers”. The second element is $14 billion for the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) that can fund farm income, price support and conservation programmes. In addition, the USDA will also receive an additional $25.1 billion for food aid programmes for poor families under the stimulus bill.

The congressional legislation gives the Secretary for Agriculture broad discretion on how to distribute this aid to farmers. The precise way in which aid will be provided has yet to be decided, with Secretary for Agriculture Sonny Perdue saying further details will be given later this week. Under the Market Facilitation Programme, which was the principal way the trade aid was distributed in 2018 and 2019, most of the money went to row crop producers although there was a broader range of beneficiaries in the 2019 package. Commentators expect that the CCC funding tranche will probably follow similar guidelines, but the $9.5 billion emergency aid element specifically mentions producers of speciality crops, producers that supply local food systems as well as livestock and dairy farmers.

Impact on direct budgetary support for U.S. farmers

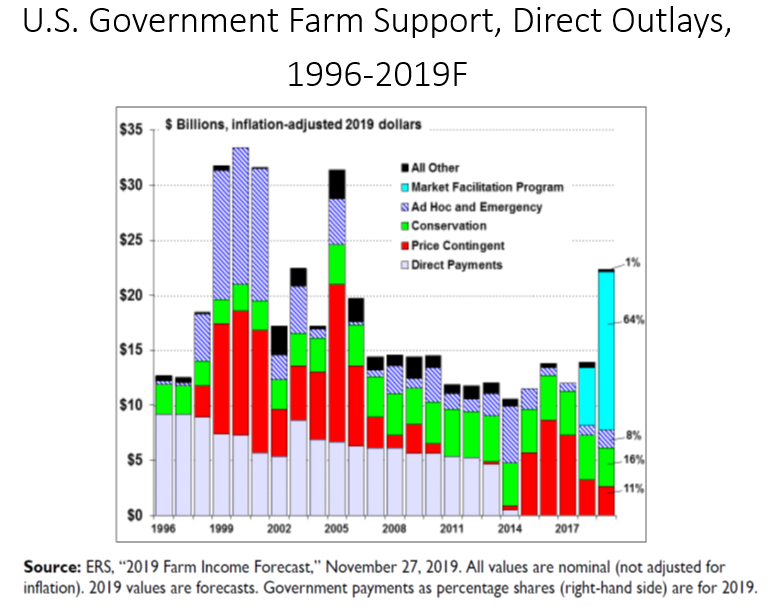

The pattern of U.S. government support in the form of direct payments to farmers in recent years is shown in the following chart. The figures are shown in nominal dollars, despite the misleading legend included in the chart, as is confirmed in the notes to the chart.

The U.S. ended decoupled direct payments in the 2014 Farm Bill and moved instead to counter-cyclical payments. In addition, conservation payments as well as ad hoc and emergency aid payments make up a significant chunk of farm support. For a description of the U.S. farm safety net after the 2014 Farm Bill, see my 2016 post, although further changes were introduced in the 2018 Farm Bill. The Market Facilitation Program is particularly important in 2019 where it includes a significant element of the 2018 Program payments that were paid in the 2019 calendar year. The chart does not include the subsidies paid by the government for crop insurance.

Notes: Data are on a calendar-year basis and reflect the timing of the actual payment. Although the chart states that the figures are in inflation-adjusted 2019 dollars, this is not the case and the source in the original notes that all values are in nominal terms. “Direct Payments” include production flexibility contract payments enacted under the 1996 farm bill and fixed direct payments of the 2002 and 2008 farm bills. “Price-Contingent” outlays include loan deficiency payments, marketing loan gains, counter-cyclical payments, Average Crop Revenue Election, Price Loss Coverage, and Agricultural Risk Coverage payments. “Conservation” outlays include Conservation Reserve Program payments along with other conservation program outlays. “Ad Hoc and Emergency” includes emergency supplemental crop and livestock disaster payments and market loss assistance payments for relief of low commodity prices. “All Other” outlays include cotton ginning cost-share, biomass crop assistance program, peanut quota buyout, milk income loss, tobacco transition, and other miscellaneous payments.

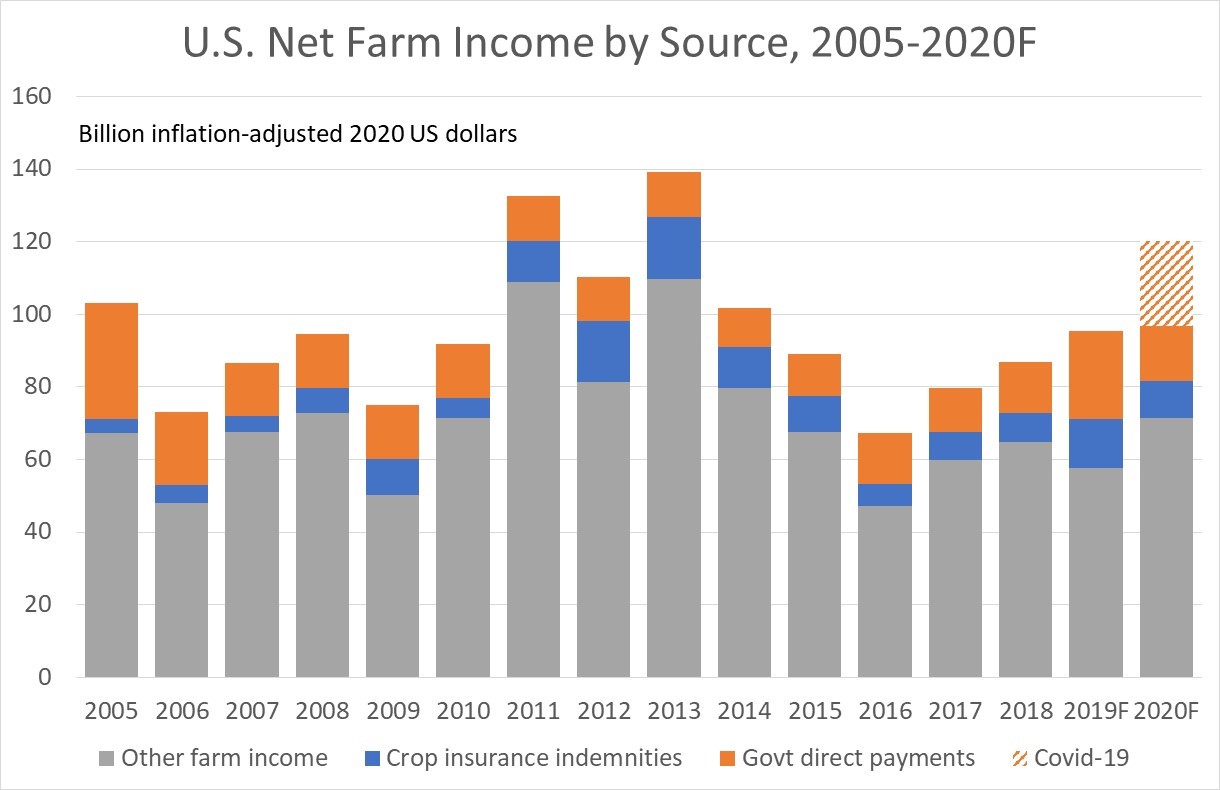

The next chart shows the importance of U.S. government support to farmers relative to net farm income. This chart is updated to 2020 based on the first USDA forecast of 2020 farm income made on 5 February 2020 (thus after the announcement of the U.S.-China partial trade deal and the outbreak of coronavirus in China and just after the first cases had been announced in Italy, but before the severity of the economic consequences of the measures needed to slow the spread of the disease had become apparent). This chart has been converted to inflation-adjusted 2020 US dollars and includes crop insurance subsidies as well as direct payments to farmers.

Note: Covid-19 emergency aid package of $23.5 billion has been added assuming no change in other government payments or other farm income.

For the purpose of illustrating the impact of the CARES Act farm aid package, I have simply added it to the farm aid and other farm income amounts as projected by the USDA in early February. If these projections remain valid, then total farm support would amount to about 40% of U.S. farm income this year. However, as for the 2018 and 2019 Market Facilitation Program payments, some of the 2020 payments would probably be made in the 2021 calendar year.

On the other hand, the aid package has been driven by concerns about falling prices and falling incomes as a result of the covid-19 outbreak. This would result in lower total farm income than shown in the chart. Lower prices and incomes would trigger higher payments also under the U.S. counter-cyclical programmes. The final outcome could thus be greater support and lower total farm income than shown in the chart, thus pushing the share of support even higher than the 40% estimated here.

Update 17 April 2020: The U.S. Secretary for Agriculture today announced details of the immediate emergency package. This will amount to $19 billion direct assistance to farmers, made up of the $9.5 billion emergency aid package under the CARES Act plus a further $6.5 billion in CCC funding using its existing credit line authority. The further $14 billion made available in the CARES Act for the CCC will not become available until July and is thus held in reserve. Secretary Purdue has indicated that there will almost certainly be more aid announced in the coming months which the CCC funding can be used to finance. Additional details on how the package will be divided are included in this press release from the Chair of the Senate Agricultural Appropriations Committee John Hoeven. For further background, see this briefing from agricultural economists at the University of Illinois.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Photo credit: Monterey County irrigation by Richard Masoner, used under (CC BY-SA 2.0) licence

Small scale independents make up a considerable portion of the farming sector and these look likely to miss out i both the UK and USA. Farm businesses with PAYE taxable employees will be in the $2 trillion US farm stimulus package, as they might be under DEFRA measures. There are thousands of local operators where the owner is the employee which provide an essential service. Their small pay reflects their profits, and many will spend on new machinery rather than a family holiday. They are not good at book-keeping, tax planning and use so-called accountants who provide no advice. They have been affected by Corvid19 as much as any other. Small business losses are relatively similar to those of larger companies, but less well calculated and presented. Small businesses need to be recognised in this crisis.

Comment edited –

Small scale independent farm related businesses make up a considerable portion of the farming sector in both the UK and USA and it looks likely that they will both miss out. Larger operators in the sector with well kept accounts and a knowledge and skill to apply for funds will be the ones to benefit from the $23.5 billion package in the US and its UK counterpart. Payment will be based on PAYE taxable employees and other measures.

There are thousands of rural operators (and also outside farming) where the owner is also the employee. Many provide an essential service – they are a part of the ‘gig’ economy. Their small pay of the owner reflects the variability and uncertainty of their profits than any clever tax avoidance, and many of these in farm services, contractors and custom operators will spend on new machinery rather than a family holiday. Generally speaking they are not good at book-keeping, tax planning and their accountants provide little advice. Small operators have been affected by Corvid19 as much as larger businesses and their losses are similar to those of larger companies, but less well calculated and presented. Small businesses need to be recognised in this crisis.

Alan, thanks for the analysis. According to my calculations, based on FAPRI’s recent update for the U.S. farm economy, and assuming that Govt. payments under the CARES Act in 2020 will amount to 16 billion $ as suggested by Trump (another part may be distributed in 2021), U.S. net farm income could remain about stable in 2020. Total Govt. payments would then exceed 33 billion $, roughly 35% of net farm income. My question: is there a lesson for the next CAP reform and the need to strengthen the risk management system for European agriculture?

@Jean-Christophe

Many thanks for your additions. Indeed, if the USDA only pays out a proportion of the allocated CARES Act funds in 2020, the impact on farm income and the relative importance of government support payments would be reduced. It will be important to see the details when the USDA gets to announce them.

You raise the interesting question whether there are lessons for an increased role for risk management in the future CAP. At this early stage in the coronavirus lockdown (up to end March) there has been relatively limited adverse impact on EU agricultural markets, the exceptions being beef and lamb which have been hit by the loss of restaurant demand which was the main consumer of high-value cuts, and some speciality sectors like the ornamental sector. Greater disruption is possible in the coming months especially if there is a fall in export demand or the availability of seasonal workers in certain sectors is restricted.

I would say that the CAP has the policy flexibility to respond to market disruption but not necessarily the budget. This reflects the relatively inflexible structure of the EU budget more than any ceiling on available funds per se. For an EU-wide crisis that affects all agricultural sectors, the EU budget will never be able to cope on its own.

This rationale holds true also for other sectors, and is the rationale behind the Temporary Framework for State Aid Measures introduced by the Commission in response to the COVID-19 outbreak in March. “Given the limited size of the EU budget, the main response will come from Member States’ national budgets”. Under the Temporary Framework, Member States have the possibliity to provide up to €100,000 per farm in state aid following rapid approval by the Commission, provided the aid is not fixed on the basis of the price or quantity of products put on the market. In addition, Member States can top up this amount by de minimis aid with a ceiling of €20,000 per farm which does not require Commission approval.

If we multiply €120,000 per farm by the approximately 6.5 million beneficiaries of EU direct payments, then the theoretical total pot of money available in the EU for farm support is €780 billion if Member States decide there is a need to activate it. Clearly, we will never come anywhere near this theoretical maximum but it is helpful to be reminded of the firepower that is available.