I have discussed previously on this blog (here and here) that Ireland faces particular challenges in meeting its EU reduction targets for the non-Emissions Trading Sector in 2030 under the EU’s Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) because of the high share of agricultural emissions covered by the ESR.

Ireland has an EU obligation to reduce ESR emissions by 20% compared to 2005 levels by 2020, and by 30% by 2030. The agricultural sector contributes 32% of national emissions, but 45% of the emissions regulated by EU legislation. The other regulated sectors include transport, heat, waste and small industry.

Emissions from all these sectors must be reduced if Ireland is to avoid contributing to global warming. Assessing the impact of Irish agriculture on global warming is complicated by the fact that methane, which is a short-lived greenhouse gas, makes up 60% of its total emissions. Nonetheless, net emissions from the agricultural and land sectors (including soils and forestry) must fall if Ireland is to meet its medium-run targets and if the combined sectors are to approach carbon neutrality by 2050.

In its recent Climate Action Plan, the Irish government spelled out detailed sectoral targets for 2030 for the first time. Agriculture has been assigned a reduction target of 10-15% relative to projected 2030 emissions with current policies in place (or a 10% reduction from 2017 levels). In absolute terms, the requirement will be to reduce annual agricultural emissions from 20 million tonnes (Mt) CO2eq in 2017 and 21 Mt CO2eq in 2030 to between 17.5 – 19 Mt CO2eq in 2030.

In terms of a carbon budget, the challenge for agriculture is to achieve 16.5-18.5 Mt CO2eq. cumulative methane and nitrous oxide emissions abatement between 2021 and 2030 with additional measures.

The Irish Government set up a Climate Change Advisory Council under the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Act in 2015 to recommend to government the most cost-effective manner of achieving reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in order to enable the achievement of the national transition objective as well as the international obligations of the State (Disclosure: I am appointed a member of this Council, but the opinions expressed in this post are my own and should not be attributed to the Council).

Climate Council Annual Review

Each year the Council produces an Annual Review that examines the country’s performance in reducing emissions and whether it is on target to meet its international obligations. In its latest Annual Review 2019, it examined the challenge of reducing agricultural and land sector emissions for the first time. It makes a number of recommendations.

First, the Council endorses immediate action to implement the mitigation measures identified by Teagasc, the Irish research and advisory agency, in its Climate Roadmap based on a detailed Marginal Abatement Cost Curve analysis (the Council has published a Working Paper that provides a further discussion of many of these mitigation measures). The measures proposed include extending the grazing season, substituting protected urea for calcium ammonium nitrate, liming to optimise soil pH, low-emissions slurry spreading, improved drainage on wet mineral soils, afforestation, managed rewetting of organic soils and peatlands, and reduced fossil fuel consumption.

Second, the Council calls for increased research into longer-term mitigation options where a high priority should be technologies to reduce methane emissions from ruminant livestock. There are promising options using either vaccines or feed additives under development but these may be more readily adopted in confinement systems. Research to ensure such technologies are also available for grazing livestock should have a high priority to maintain the competitive position of grass-based production systems.

Third, the Council sees an opportunity both to reduce emissions and to protect and enhance the income of beef producers by incentivising a reduction particularly in suckler cow numbers. The critical point is that many beef farmers consistently lose money on beef production and subsidise this activity from either off-farm income or their Basic Payment.

The Council recommends that restructuring CAP payments to link a portion of them to a commitment to reduce numbers, what it calls an extensification scheme, could be a win-win situation. It could maintain or even enhance the income of participating farmers while reducing livestock emissions.

Because of the ongoing situation of low cattle prices in Ireland with emotions running high, this recommendation was met with mixed reactions and has been widely misunderstood. According to the Irish Farmers’ Association, the main Irish farm union, the recommendation was based on a flawed logic of cutting production in a country with carbon efficient beef production and risked fuelling climate destruction. The president of the Irish Natura and Hill Farmers’ Association called for the suspension of the Council pending a review because it focused on reducing the suckler herd while alleging that it gave the dairy sector a free pass.

Indeed, a lot of newspaper commentary suggested that the Council was ‘demonising the suckler sector’. An editorial in the main farming newspaper the Irish Farmers’ Journal admitted that “No one can defend maintaining unproductive cows within the national herd and a focus/policy aimed at removing these is logical in the context of reducing emissions. But a report that makes broad sweeping statements in relation to the future of a sector that has been shown to underpin over 50,000 jobs in rural Ireland needs to be challenged.”

Other farm groups were more positive in their evaluation. The President of the Irish Creamery Milk Suppliers’ Association welcomed the reasonable tone of the Council’s report but argued for more supports to be put in place for farmers. The Irish Cattle and Sheep Farmers’ Association who have long called for a voluntary beef cow reduction scheme to be introduced at European level support the idea of a Suckler Redirection Scheme seeing it as a way of increasing the profitability of the beef sector. In similar vein, a group of leading beef farmers has recognised that in the Irish context the number of suckler cows will have to be drastically reduced in order to rebalance the beef market.

In an opinion piece in the Farming Independent today, I set out to put flesh on the bones of the Council’s recommendation for an extensification scheme for livestock numbers. In this post, I elaborate on that article and take the opportunity to discuss some of the objections that have been raised following the Council’s report. The key take-home message to keep in mind is that the Council’s recommendation can potentially improve the income of suckler farmers while also assisting to reduce emissions.

Industry context

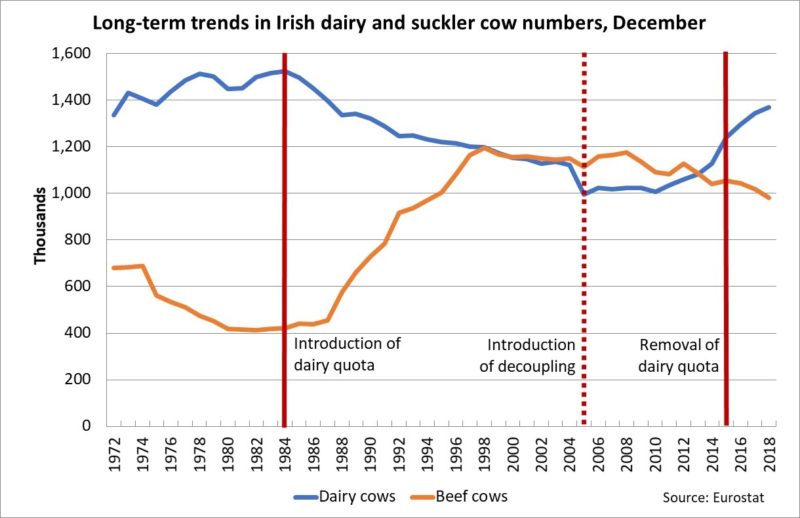

The context for this discussion is the removal of dairy quotas in 2015 which has allowed a rapid expansion in dairy cow numbers, an expansion that began some years previously (see figure below). The introduction of dairy quotas was associated with a rapid build-up in the suckler cow herd. Dairy farmers used their spare resources to finish their calves and beef farmers moved into suckling to provide replacements for the missing calves. Since the introduction of decoupling in 2005 there has been a slow decline in the beef suckler cow herd, though at a slower rate than what had been anticipated given the low profitability in the sector. Since the low point in total cow numbers in 2010, suckler cows have declined by a further 12% by 2018 while dairy cows have increased in number by 36%.

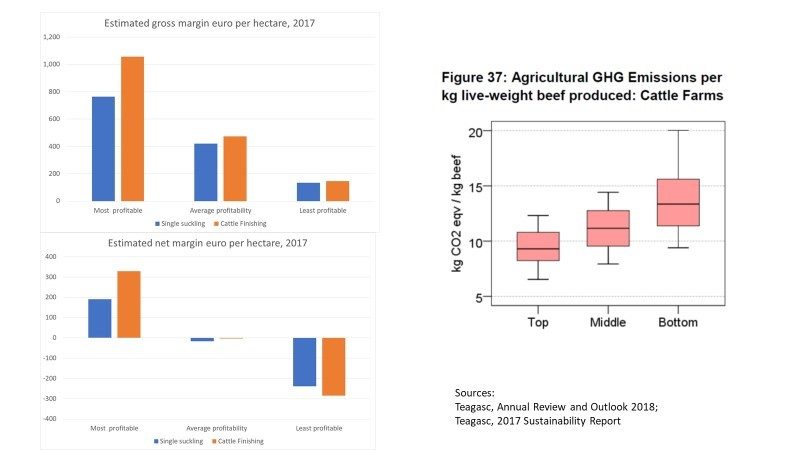

The low profitability in the sector is illustrated in the next figure. While both suckler cow (cattle rearing) and cattle finishing farms have a positive gross margin, when overhead costs are factored in they have a negative net margin on average (the figures are estimated for 2017 but this has been a consistent pattern over many years). The margins shown here include coupled payments but exclude decoupled direct payments. Nor do they make any allowance for the costs of family labour or family-owned land (for further details on how Teagasc calculates these margins, see this fact sheet on the cattle finishing enterprise as an example).

Equally significant is the variability within the sector. While the top third of beef farms by economic performance had a significantly positive net margin, the bottom performers have a significant negative net margin. As can be seen from the chart on the right, economic performance is positively correlated with emissions performance. Those beef farms that are losing money are also the farms that contribute the highest emissions per unit of beef produced.

Thus many Irish beef farmers are subsidising beef production either out of off-farm income or their decoupled direct payments or agri-environment payments. If the argument is made that direct payments should continue because they support the incomes of farmers in the sector, it makes sense to ask whether these payments might not be directed in a more effective fashion.

Furthermore, the sector faces serious downside risks, both from the gradual opening of the EU market to cheaper imports under free trade deals and, more immediately, from the likelihood of a no-deal Brexit. The tariffs that the UK has announced it would impose on beef imports in the event of a no-deal Brexit are almost halved compared to the level it currently levies as an EU Member State. In addition, it plans to open a zero-duty tariff rate quota of 230,000 tonnes on an erga omnes basis to all exporters. There is also the risk of a further sterling depreciation in the event of a no-deal Brexit. These changes in trade and exchange rate conditions will further undermine the profitability of Irish beef production.

A Livestock Emissions Reduction Scheme – how might it work?

Suppose that under the new CAP where the authorities have greater flexibility to design the payments to achieve national objectives, the government top-sliced some of the Basic Payment money to incentivise a reduction in livestock emissions as part of the proposed new eco-scheme. This might be called a Livestock Emissions Reduction Scheme. It would pay farmers for a reduction in their emissions compared to a base year, assume this is 2017.

Just to illustrate how the scheme might work, assume that the payment rate was €35 per tonne of CO2 equivalent abated. This is the rate that the Council has recommended the Irish carbon tax in the non-farm sector should be in the coming budget.

Total emissions from the average cattle farm in Ireland in 2017 amounted to just over 140 tonnes of CO2 equivalent. If a livestock farmer with total emissions of 140 tonnes CO2 equivalent in 2017 agreed to reduce his or her emissions to 100 tonnes by reducing numbers, this would trigger an additional carbon abatement payment of €1,400.

According to Teagasc, the average level of emissions across all cattle farms was 11.9 kg CO2 equivalent per kg beef of live-weight produced in 2017. Assuming a liveweight at slaughter of 600 kg, a payment at this level would be equivalent to €250 per animal.

Alternatively, the government could experiment with a reverse auction scheme. It could announce a desired level of emissions reduction (lower initially to avoid a flood of beef disrupting the market but slowly increasing) and invite bids for compensation to reduce emissions. The compensation level would then be set at the level of the lowest losing bid and all farmers who had offered a bid lower than this level would be admitted to the scheme.

Although the scheme would be open to any livestock farmer, including dairy farmers, those expected to enrol would be those farmers with negative income from beef farming at the moment.

Of course, many details would need further consideration. Would the scheme pay only for reductions in suckler cow numbers or total livestock numbers? Would a farmer be paid annually or be asked to enter a multi-year commitment? How would the payment level be decided? These details should be worked on by the Department together with the farm organisations.

It would also be desirable to link payments under a carbon abatement scheme to positive environmental action on the participating farms. Again, how best this might be done should be a matter for further discussion with farm and environmental groups.

The Council’s report sets out a number of illustrative scenarios relating a reduction in suckler cow numbers to the expected reduction in emissions. In the most ambitious scenario in which suckler cow numbers halved and returned to pre-milk quota levels and assuming a payment level of €35 per tonne of CO2 equivalent abated, the amount of Basic Payment required to fund this scheme would be €75 million. This represents just over 6% of the total Basic Payment.

This sum could easily be raised by capping the overall amount of Basic Payment that any farm could receive. This capping would mainly affect feedlot-type cattle rearing operations and some larger dairy farms.

Suckler farmers participating in the scheme would continue to receive their Basic Payment and would in addition receive an Emissions Reduction Payment. This is why these farmers would gain under the Council’s proposal as participation in the scheme would be on a voluntary basis. Farmers would only enrol if it made them better off.

What about the objections?

As previously observed, a number of criticisms were made of the Council’s recommendation when its report was launched. Let us consider these in turn.

Does it make sense to reduce production? Let’s think about this first from the point of view of economic theory. A private actor, such as a farmer, decides on the level of production in the light of his or her marginal private costs. No account is taken of negative externalities, such as the costs imposed on society due to pollution or climate emissions (or of positive externalities that may be provided, for that matter). As a result, the actual level of production in a market economy where no attempt is made to internalise these negative social costs (that is, require the farmer to take them into account in his or her decision-making through tax, subsidy or regulatory policies) will be greater than what is socially optimal and beneficial. So yes, taking account of a negative externality will correctly lead to lower production.

This standard argument from economic theory is reinforced in this instance by the fact that, even in private terms, production is not economic for many farmers. As we have seen, many beef farmers in Ireland are subsidising beef production out of their direct payments or off-farm income.

But what about carbon leakage? We can note that the Irish government’s objective is to eliminate the negative impact of Irish economic activity on climate warming by mid-century so it is emissions produced within Ireland that are relevant. Also, the state has EU legal obligations that it must achieve and should strive to do this in a least-cost manner.

However, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are global pollutants and the argument is made that production in Ireland, which is globally relatively GHG-efficient, may be replaced by production in other countries that is less GHG-efficient and thus global emissions may increase.

This is an empirical argument. Whether this outcome is likely to occur or not will depend on the alternative sources of beef supplies, their actual GHG-efficiency, the commitments taken by these countries to reduce their own GHG emissions, and on whether steps are taken to also limit beef consumption at the same time.

Regardless of the empirical evidence, the fallacy in the carbon leakage argument is that it takes a single productivity indicator (output per unit of emissions) as the sole basis for deciding on the optimal location of production. Other single productivity indicators include labour productivity (output per worker), energy productivity (output per unit of energy), and land productivity (output per hectare, or yield).

No one would suggest that a country should specialise in the production of a crop with high yields alone without taking account of the value or amount of the other inputs (fertiliser, labour, chemicals etc) that are needed to generate those high yields.

Similarly, it does not make sense to argue that beef production should continue at its current level in Ireland simply because the country is a producer of relatively low-emissions beef without taking into account the cost of the other inputs that are required. The economic data presented earlier show the flawed logic of using the carbon leakage argument to defend the current level of beef production in Ireland on this basis.

Is there not a danger of deadweight? Deadweight occurs when we are paying farmers to do something that they would be doing anyway. The industry discussion above shows that the number of suckler cows is anyway slowly declining. If there is a major adverse shock such as a no-deal Brexit, this decline would be expected to accelerate. So why not simply let natural economic forces do their work?

There are various responses to this argument. One is that Ireland is currently far from meeting its 2020 and 2030 ESR reduction targets. These targets are expressed as annual ceilings that must be met (taking into account the flexibilities that are set out in the relevant legislation). If the annual ceilings are exceeded, taking into account any allowances that have been banked from previous years, then the state must seek to purchase allowances from other Member States. This use of public expenditure represents a transfer of resources out of the country which could better be used to support the green transition in Ireland.

Another response is that the proposal redirects money that is already allocated to the support of farm incomes. It is not proposed to increase public expenditure to achieve this reduction. My suggestion is to use the proceeds of capping large payments to individual farmers to fund this scheme. This would mean, for example, that large dairy units who benefit from the ‘emissions space’ freed up by a livestock emissions reduction scheme would also make a contribution. If the public expenditure is already allocated, no question of deadweight arises.

It is worth noting that the conditions attached to the €100 million aid package for Irish beef funded equally by the EU and the Irish government as a response to low market prices – the Beef Exceptional Aid Scheme – requires participants to reduce the production of bovine livestock manure nitrogen (total figure) per herd by 5% for a target period (1 July 2020 – 30 June 2021) compared to a reference period (1 July 2018 – 30 June 2019) in order to qualify for aid.

Does paying farmers to reduce emissions run counter to the polluter pays principle? Reductions in GHG emissions in other sectors are sought either through charging for tradable permits (as in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme) or through a carbon tax on energy use in other sectors. So it would be true that paying farmers to reduce emissions would be to use a different approach than in other sectors. Again, however, the argument is that farmers will receive these transfers in any case. The proposal seeks to make these payments more effective by linking a proportion of them to emissions reductions as well as income support.

The previous graph illustrating the industry context showed that, including coupled payments but putting zero value on the farmer’s labour and land, even the least profitable third of farmers generated a small positive gross margin from beef production. If some of these farmers were to participate in the Livestock Emissions Reduction Scheme, the payment they would receive would be partially offset by the loss of this gross margin (assuming they have no ability to vary their overhead costs in the short term). So the additional payment would not translate one-for-one into additional farm income.

Aggregating up to the farm sector level, redirecting a share of direct payments from pure income support to a Livestock Emissions Reduction Scheme where eligibility for this payment would be conditional on reducing livestock numbers (and thus involve some loss of gross margin) would result in a small drop in overall farm income. This is also likely to be the case for any other potential use of eco-schemes in Pillar 1 where farmers are asked to undertake agri-environmental-climate management commitments as a condition of receiving the payment.

On the other hand, a reduction in suckler cow numbers will affect the supply-demand market balance and would be likely to put upward pressure on market prices. It is for this reason that the ICSA have long argued for a voluntary compensation-based suckler cow reduction scheme. I am not aware of any estimates of what the price uplift might be. Given the small amount of direct payments that would be used for this scheme, I would find it plausible to suppose that the price uplift would be sufficient to offset the foregone gross margin by participating farmers at the aggregate farm income level.

Would extensification reduce soil carbon sequestration? The GHG budget on which the proposal for a Livestock Emissions Reduction Scheme is based only considers direct emissions captured in the inventory accounts submitted to the EU and to the UNFCCC. It is these direct livestock emissions that are included in the ceilings set by the Effort Sharing Regulation. Changes in soil carbon are reported in the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) account in the UNFCCC inventory but are included in a separate target, the ‘no debit’ rule, for the LULUCF sector.

There is some debate about whether more extensive grazing might result in a slower uptake of carbon in the soil compared to intensive grazing. To the extent that this is the case, it would dilute the benefits to the atmosphere of reducing emissions by reducing cattle numbers, but it would not affect the benefits to Ireland in terms of meeting its legal obligations.

However, accounting for changes in soil carbon in the Irish inventories remains a work in progress with a high degree of uncertainty. With the present state of knowledge, the evidence base does not yet exist to support making changes to the inventory based on the intensity of grazing. Further research to fill in this knowledge gap is clearly desirable.

Conclusions

The Irish Climate Change Advisory Council made a number of recommendations on how to reduce GHG emissions from the agricultural sector in its most recent Annual Review. These include implementing the mitigation options identified in the Teagasc Climate Roadmap, investing in longer-term research to identify methane inhibitors that will work in grazing systems, and an extensification scheme that would compensate primarily suckler farmers for reducing their herds.

The Council did not provide specific details of how such a scheme might work, that is not its function, but in this post I have sketched out some details of a possible model. Based on this model, we can address some of the most frequent objections to the Council’s recommendation, including that it represents an attack on suckler farmers. In fact, the opposite is the case and I show that farmers who participate in such a scheme would do so voluntarily because it would make them better off. I also suggest that the price gain to those farmers who remain in the beef business would ensure that overall farm income would not be adversely affected, but this conclusion would need to be supported by further research.

Ultimately, we should be using public money to assist farmers to make the transition to less GHG-intensive uses of land. Funding a livestock reduction scheme is not a long-term solution, but it could provide the necessary breathing space to allow time for the development of viable alternative land uses. It would also be a better use of public money than purchasing allowances from other Member States to ensure compliance with our legal obligations.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Photo credit: A large herd of Limousin cattle © Copyright Eirian Evans and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Dear Mr. Matthews,

A very interesting analysis of some of the options for Irish agriculture.

A small note concerning the use of mineral fertilizer; to my knowledge, the Irish government proposes to substitute the currently widely used calcium ammonium nitrate (CAN) by “protected urea”, and not the other way around as stated in the article.

@Willem, Thanks, you are correct and that was the intention of my statement (which probably should read “substituting protected urea for calcium ammonium nitrate currently used”), so good to clarify.

Dear Alan,

reading your post two questions came to my mind.

a) what is the logic behind improved drainage of mineral soils? OK. N2O emissions would decline, however, at least empirical data from Germany shows, that even for soils with a C-content of just 6% (typically gleysols) this N2O-effect is outweight by an increased decomposition of the soil C-stock.

b) Is there not the clear and present risk that such a scheme would sacrifice agriculturally related biodiversity (if I remember right the farmland biodiversity indicator do not look too good in Ireland, like in the rest of the EU) for the sake of climate mitigation. At least from the cattle farming systems I know, the ones with the highest biodiversity output are frequently the ones with the highest GHG-emissions and the worst profitability. And the problem is that this due to some causal reasons, these farms operate under more problematic conditions ==> manage their land less intensive ==> have a lower forage quality ==> lower weight gains.

While the 1st two are positively linked to the biodiversity output, the later two lead to higher GHG emissions per kg.

Best

Norbert

@Norbert

Thanks for queries. On your first question, this is an issue for the soil scientists so I can only refer you to the Teagasc Climate Roadmap (link above) which discusses this issue (It is Measure 10 in the Roadmap). It emphasises the potential for reduced nitrous oxide emissions but does not discuss possible CO2 leakages for mineral soils (while warning that the latter would dwarf the gains from lower N2O emissions from drainage of humic (gleysols and podsols) and histic (peat) soils). The following reference in the bibliography may provide further clarification.

Paul, C., Fealy R., Fenton O., Lanigan G., O’Sullivan L., Schulte R.P.O. (2018) Assessing the role of artificially drained agricultural land for climate change mitigation in Ireland. Journal of Land Use Policy 80: 95-104.

Your second point on potential trade-offs between economic efficiency, climate mitigation and biodiversity is well taken. I think I would prefer to introduce more targeted measures to protect diversity where specific management practices are rewarded rather than simply supporting ‘unproductive’ (in the market economic sense) farming per se in the hope that this gives biodiversity benefits. But this is certainly an open question.

This is a most welcome contribution to the debate, many thanks!

Lots of things to mull over, and some good remarks already made here. Hence I confine my tuppence worth of ideas to my field, the WTO rules.

Your proposal – whatever its merits for Ireland’s contribution to reducing GHGs, in absolute and relative terms (e.g. feed tech alternatives) – looks like a new Blue Box type of farm support: pay to reduce production. This would undoubtedly raise attention in the WTO – but perhaps show a way forward without the need to resuscitate the dead Doha Round, or to enlarge the Green Box definitions for non-trade distorting support to a public good (!?). The present definitions are largely insufficient for accommodating the Paris commitments (of the EU and other Members, first of all Norway) – and we don’t want “Paris” to give a carte blanche to all sorts of GHG reduction schemes with a competition impact, or a violation of the national treatment obligation.

I am not saying this would work easily. But a closer look at your proposal is definitely worth looking at under a “WTO-cum-UNFCCC” perspective!

@Christian

Thanks for comment. In general I am not in favour of paying farmers to reduce production, if production in an area is causing environmental damage the polluter pays principle suggests the better instrument to address this is a levy or regulation. So I am not convinced the Blue Box would make up for any possible shortcomings in WTO rules that might seem to restrict environmental payments (I note that the US initially notified its Conservation Reserve Program under the Blue Box but now notifies it as an agri-environment programme in the Green Box). In this case I make an exception due to particular circumstances in Ireland (a) a legally binding emissions reduction obligation where agricultural emissions contribute almost one half of the total (b) an enterprise which both contributes significantly to emissions but which is also unprofitable for many farmers and which faces severe downside risks (c) an existing system of subsidies that provides all the income for these farmers. Thus why not make a more rational use of these subsidies? This is very much decision-making in a second-best world.

Dear Mr Matthews,

Thank you for this analyses. One question :

Direct payments have been created in the 90’s to compensate the loss of income induce by the WTO AoA. Am I right? If so, it is not the farmers who subsidised their production with their direct payment but the EU. And was those subsidies designed for that purpose ?

Another interesting point in your paper. You state that the less economically efficient beef producers have the highest GHG emissions. Could you give the references of this affirmation? Is this specific to Ireland or the same constatation can be extrapolated to all EU member states?

@desfilhes

You are right that direct payments were first introduced in the 1990s to compensate farmers for the reduction in minimum intervention prices as part of a policy adjustment to enable a successful outcome to the Uruguay Round which led to the creation of the WTO. These payments were later largely decoupled in the 2003 CAP reform. With the (partially) coupled payments in the 1990s, the EU required farmers to produce in order to receive the payments but with decoupling after the 22003 reform this is no longer the case. A farmer receives a payment per hectare of eligible land but is not required to produce or to continue unprofitable production. The idea was to allow production decisions to be taken in the light of market returns while ensuring a basic income support to the farmer. If a farmer decides to continue with unprofitable production and to cover his or her losses out of the direct payment, that is their choice and not something that is required by the EU.

The source for the inverse relationship between economic performance and emissions intensity is the work done by Teagasc and reported in its Sustainability Report 2017 and is shown as Chart 37 in the second figure in the post. You can download the report here https://www.teagasc.ie/publications/2019/national-farm-survey-2017-sustainability-report.php

You are promoting a reduction in one of the least environmentally sectors we have whilst suggesting dairy stays as it is. Nitrogen use, exportation of slurry on paper only, Fawac concerns, zero grazing are all the norm for a dairy herd now. That sector owes Irish Banks 100m plus so we need to keep them going. Our emissions have gone up due the excessive expansion of this sector. You should if you are part of the climate advisory committee be promoting an actually greener future not one for balance sheet. Also this post makes no reference to the possible carbon sequestering capabilities of hedgerows small woodlands and soil or the lack of research into same. Farmers are the keepers of the green around you and all our present forestry stock privately or state owned is used to offset current national emission calculations. Personally, I think people need to get up from their desks, take a look around at whats actually going on and see what Agriculture does do for the environment. Its simple why not stop intensive farming and encourage extensive farming. We re not making any money anyway so why line the pockets of everyone else paying for feed fertiliser machinery methane inhibitors etc etc. Oh but maybe thats exactly why not.

@Sarah

Thanks for taking the time to comment on the post. Indeed, you are absolutely right that emissions from the dairy sector cannot be ignored (and not only emissions, but also nitrogen surpluses and ammonia and impacts on biodiversity should be taken into account). You are also right to point out that this post only addresses emissions from the suckler herd which because of its more extensive nature has a smaller environmental footprint per hectare than dairy farming.

There is no one silver bullet to addressing agricultural emissions. Bending the curve and reducing absolute emissions will require a broad range of initiatives. The reason for highlighting the suckler herd issue in this post is that, while emissions per hectare are higher in the dairy sector, emissions per unit of output are higher in the cattle sector according to the Teagasc Sustainability Report 2017 (this comparison is done according to the official weighting of methane and nitrous oxide emissions; the figures would differ if another weighting metric such as GWP* were used but my expectation is that this would not alter the ranking, especially if emissions per euro of value added were used).

Essentially, the value added in cattle production is so low that it would make sense to seek a targeted reduction in suckler cow numbers and to use CAP payments to incentivise farmers to do this. But in addition, measures to reduce emissions on dairy farms will also be required.