This post first appeared on LinkedIn on June 11, 2023 and is reproduced here without amendment. Since that date there have been national parliamentary elections in Greece and Spain which in many respects confirm the analysis presented here. Furthermore, it is now agreed to increase the number of seats in the European Parliament by 15, with additional seats going to France, Spain and the Netherlands (2 each) and 1 additional seat to Austria, Belgium, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Latvia, Ireland and Denmark.

A couple of weeks ago the Council of the EU confirmed that the next elections to the European Parliament (EP) will take place from 6 to 9 June 2024. So in exactly one year’s time we will know the outcome of the election and the political composition of the next Parliament.

It seems as if political change is on the way. Right-wing parties have kept power or made gains in recent elections in Greece, Finland, the Netherlands, Hungary, Sweden, and Italy. In upcoming elections in Spain the balance may also shift. Recent opinion polls in Germany have shown an upsurge in support for the right-wing AfD which is now the third-strongest political force, only slightly behind Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrats at second and the centre-right CDU/CSU main opposition bloc first. In France, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National is now polling ahead of Macron’s LREM.

A relevant question is what this shift in political sentiment in Europe might mean for the political composition of the next European Parliament and what this, in turn, might mean for the EU’s political project. Most immediately after the election, the political composition of the Parliament will influence the choice of Commission President. This will be the case regardless whether EU leaders agree to follow the spitzenkandidaten process or not. While Commission President von der Leyen comes from the center-right EPP political family and the presumption is that she would be re-confirmed should she decide to stand again, it is worth recalling that her appointment was approved by the Parliament on the last occasion by only a bare majority (she received 383 votes when 374 votes were needed). The context for another vote would be very different. She would be standing on her record for four years as Commission President and not as a former German Minister for Defence. But whether she would receive the same level of support for her flagship Green Deal project remains an open question.

The political composition of the Parliament will also be reflected in the apportionment of committee chairs, in the appointment of rapporteurs, as well as in the outcome of votes on legislative files. Although there is still one year to go, we can follow the trend by looking at seat projections for the different political groups. This post summarises the information available as of the end of May 2023.

Seat projections in the European Parliament

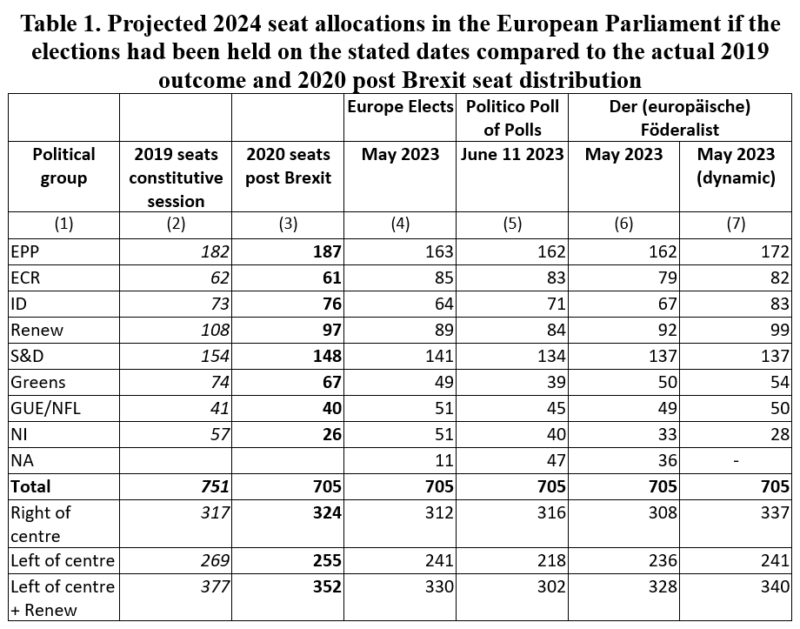

Table 1 below shows the actual number of seats held by each political group as officially announced by the newly-elected European Parliament 2019-2024 at its constitutive session (Column 2). The 2019 EP elections were held when the UK was still an EU Member State and the Parliament had a larger number of seats than it has now. Following Brexit on 31 January 2020, of the 73 seats vacated by UK MEPs, 27 were redistributed among 14 Member States, while 46 remain available for potential EU enlargements and/or the possible creation of a transnational constituency in the future.

Sources: 2019 seats at the constitutive session European Parliament; 2020 seats post Brexit Clifford Chance LLP; Europe Elects; Politico Poll of Polls accessed 11 June 2023, Der (europäische) Föderalist

Column (3) shows the composition of the political groups immediately after Brexit took place. The biggest change occurred in independent members (referred to as NI Non-Inscrits) given that the Brexit party had emerged as the single largest party in the UK with 29 out of 73 seats but it did not affiliate with any of the existing political groups. The S&D, Greens and Renew also lost seats, while the EPP made a gain of five.

The remaining columns (4-7) in the table show the projected seat distribution among the political groups in the 2024-2029 Parliament if the election were held on the dates mentioned as projected by three different organisations. As there is no EU-wide polling, these organisations extrapolate their projections from the support at Member State level for the political parties aligned with the EP political groups, while taking account of factors such as specific electoral system rules. The differences in the projections reflect the choice of national polls used on which to base the extrapolations, the different methodologies used by the organisations in making their extrapolations, and not least the different timing when the projections are made. The Politico Poll of Polls is updated daily, while projections by Europe Elects and Der (europäische) Föderalist are updated monthly.

Each of the three poll projections includes a group referred to as NA Non-Affiliated. This is different to NI Non-Inscrits which refers to MEPs who make a deliberate choice not to affiliate with a political group. The NA group refers to potential MEPs elected for political parties at the national level – usually newly formed parties or parties that were not previously successful in EP elections – and who have not yet declared which political group they will seek to join.

The seat projections are influenced by the different treatment of the NA group by the different organisations. The Politico projections automatically assign new parties to the NA group, as does the primary Der (europäische) Föderalist projection. Europe Elects attempts to align new parties with existing political groups based on public statements or direct communication with the parties, hence its figure for NA MEPs is lower than for the other two organisations. However, Der (europäische) Föderalist also prepares a dynamic projection (Column 7), in which it takes the NA group of MEPs elected for political parties at the national level that have not yet indicated a preference for a political group and assigns those MEPs to a political group based on their stated political platforms. Thus, column (7) differs from column (6) in that all MEPs reported in the NA group in column (6) are distributed among the political groups in column (7) according to this assessment.

Keeping in mind these differences in how to interpret the seat projections, there are strong similarities in the projections between the three organisations. The relevant comparison to make is with the seat distribution in 2020 post Brexit which has the same number of total seats. The story is of a fall in the number of seats of the traditionally more pro-Europe centre parties and a rise in support for both extremes. However, on the right, the gains are made not by ID but by the ECR, while on the left the gains are made by the Left GUE/NFL.

However, we must be cautious in translating these figures into a projection of the overall balance in the Parliament because of the high number of MEPs reported as NI or NA in the projections. As noted above, Europe Elects attempts to assign MEPs from new parties already to a political group and has a relatively small number of NA MEPs, but on the other hand it has the highest number of non-affiliated NI MEPs. Much of the change in seats reported for the individual political groups reflects the big jump in the number of MEPs reported in these two categories (for example, in the case of the Politico poll of polls, it reports 87 MEPs as either NI or NA compared to just 26 MEPs in the post-Brexit 2020 distribution. The increase of 61 MEPs in these two groups drives the fall in seats for the identified political groups).

Against this background, the fact that both the ECR and the Left political groups show an increase in the projected number of seats is even more striking. For this reason, the dynamic projections by Der (europäische) Föderalist in Column (7) are particularly relevant. These show that a significant number of seats gained by new parties are aligned with the far-right and will affiliate with the ID. In the dynamic projections, both the ECR and the ID gain seats at the expense of the centre-right EPP but also from the centre-left S&D. The Left group gains seats at the expense of the Greens, while the liberal Renew group would maintain its seat position.

Overall, comparing the Der (europäische) Föderalist dynamic projections in Column (7) with the immediate post-Brexit seat distribution in February 2020 in Column (3) probably provides the cleanest comparison of the likely balance of power in the new Parliament based on voting intentions today. Looking at the broad centre-right and centre-left groupings, we see an increase in projected seat numbers for the centre-right of 13 and a decrease in projected seat numbers for the centre-left of 14. While this swing is consistent with the media reports of a swing towards the populist right, it is not the dramatic swing that might be inferred from these reports. Further, with one year to go until voting, there are many factors that could either strengthen or reverse this trend.

Trends since 2020 in seat projections

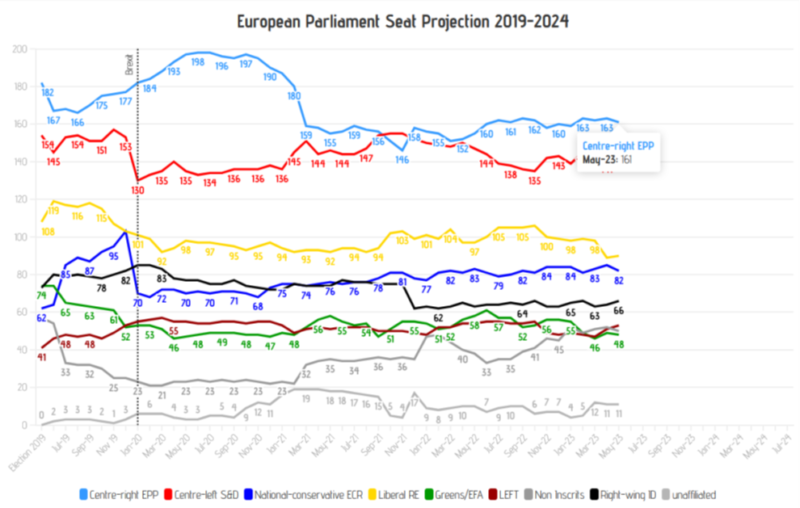

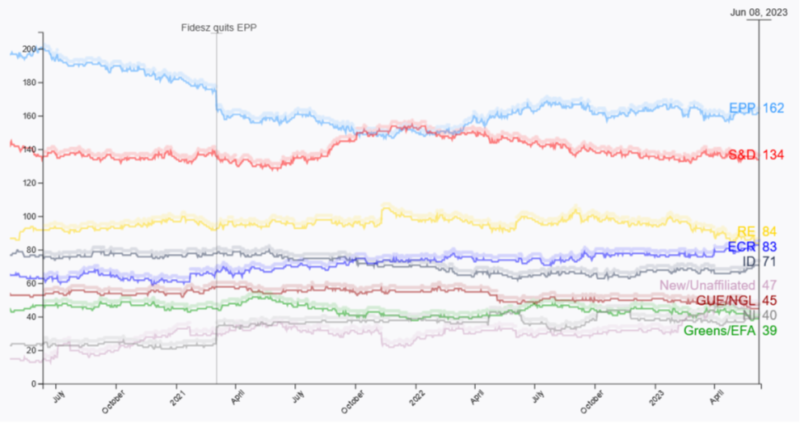

Table 1 shows a comparison of seat projections at a point in time. It is also possible to track the changes in political support through time. The following chart shows the seat composition as projected by Europe Elects over time. One immediate point to note is that the post-Brexit starting point in terms of seats projected for the political groups shown in the figure is rather different to the seat distribution shown in Table 1, and this influences the reported trend over time. The years 2020 and 2021 were dominated by governments’ handling of the COVID-19 crisis, while the period since February 2022 has been dominated by responses to the Ukraine war, the cost of living crisis marked by high inflation, and awareness of the growing number of asylum seekers.

The major dynamic in the Europe Elects poll figures is the large increase in the number of NI MEPs which occurred during 2021and which, other things equal, will put downward pressure on the seat numbers for the identified political groups. Against that background, the EPP appears to be recovering support since the beginning of 2022 while the S&D has lost support. There is also a significant loss in projected seats for the Greens and Renew, while support for the ECR is growing. The picture for ID is more mixed given it was projected to lose a significant number of seats around December 2021, but it has recovered some of that lost ground since then.

The trends in the Politico projections are very similar, again taking account of the significant increase in the number of MEPs reported as NI or NA. The one difference is that Politico does not show increasing support for the Left group in the past 18 months but, as noted above, some support for the Left may be reflected in the growth of protest parties not previously represented in the Parliament. Politico assigns these automatically to NA while Europe Elects uses additional information to assign them to the political groups they will most likely align with in the Parliament.

The importance of turnout figures

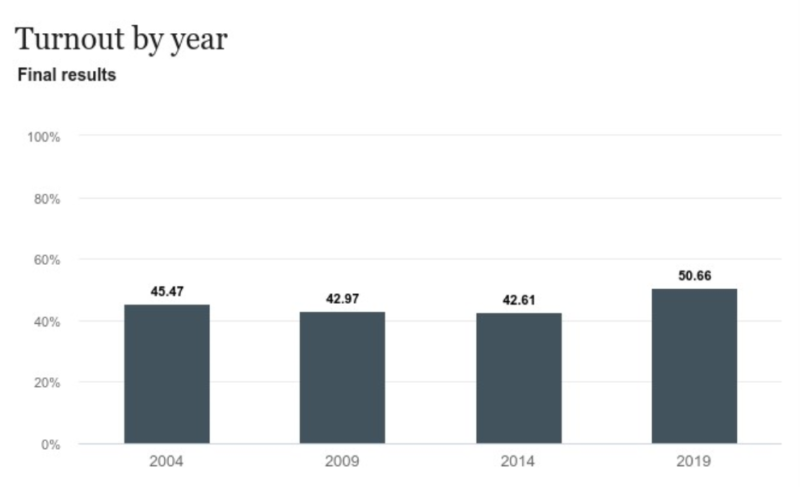

One issue to keep in mind in interpreting seat projections in the European Parliament based on support for national political parties is that turnout percentages (the proportion of the electorate who actually vote) is usually much lower for EP elections. The 2019 election was the first since 1979 where voting rates for the EP elections increased compared to previous elections, but still only just over half of the electorate turned out to vote (see figure below). According to the European Parliament’s post-election Eurobarometer survey, a significant increase in young people with a pro-European mind-set cast a vote in the 2019 European elections, which boosted the Greens and liberals and resulted in ambitious laws to curb climate change. Interestingly, the European Parliament’s latest Eurobarometer survey finds that interest in the next European elections is at 56% among citizens, six percentage points higher than one year before the last European elections. What is more: two-thirds of citizens (67%) say they are likely to vote, when 58% said so in 2018. While a positive sign, how this might affect the political composition of the next Parliament obviously depends on the political attitudes of those who decide to vote.

Conclusions

This post examines the possible political composition of the next European Parliament based on polling intentions at national level extrapolated to the EP elections if the election were held today (more accurately, in the past month). The recent trend towards greater support for right-wing parties in national elections is confirmed in the seat projections. More specifically, the new European Parliament based on voting intentions today would see larger numbers of far-right and far-left MEPs and a reduction in the number of MEPs in the more centrist parties.

While there is an evident and significant shift in the projected political balance in the Parliament, it is rather less dramatic than might be inferred by media reaction to the string of successes by right-wing parties in national elections. One possible explanation is that these parties also performed well in the 2019 European Parliament elections. In France, the right-wing party of Marine Le Pen Rassemblement National was the largest party in 2019 with 22 seats (ID) followed by Macron’s liberal coalition led by LREM (Renew). In Italy, the right-wing Lega Salvini Premier (LN) won the largest number of seats with 28 (ID) followed by the centre-left Democratic Party (PD) with 19 seats (S&D) and the populist M5S with 14 seats (NA). In Poland, the right wing PiS was the single largest party and won 26 seats (ECR) followed by the European Coalition which split 17 seats for the EPP and 5 seats for the S&D. In Hungary the right-wing coalition around FIDESZ won the largest number of 13 seats (EPP) with 4 seats for the centre-left Democratic Coalition (S&D). Given this starting point, the fact that we observe a further incremental increase in projected seats rather than a landslide is easier to understand.

Of course, terms such as right-wing and left-wing are a very limited form of shorthand that conceal very significant political differences within these groups on particular issues. It would be completely wrong to see these as monolithic blocs that vote in uniform ways. How specific attitudes in the Parliament to issues such as trade policy, the war in Ukraine, climate policy, the Green Deal and migration might evolve will require a more detailed analysis of the political programmes of the various groups when they are published closer to the election. The next twelve months will also be marked by greater political positioning by the different groups as they attempt to sharpen their political profiles prior to the elections next June.

This article was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit. European Parliament used under a CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2019 – Source: EP licence.