An announcement last week by Karel de Gucht, the EU Trade Commissioner, that the EU and Russia had struck a deal on remaining outstanding bilateral issues in negotiating Russia’s accession to WTO membership raises the prospect that this economic giant could become a WTO member by the end of this year.

Russia and the WTO

Russia first made its application in 1993 so has been negotiating its accession now for 18 years, by far the longest of any accession process by a WTO applicant. This reflects in part the country’s economic size (it is the sixth largest economy in the world on a PPP basis). Whereas normally 6-10 countries might seek to open bilateral negotiations with an acceding country because they had special trade interests at stake, in Russia’s case more than 60 countries made such requests.

But also China was a large economy whose WTO accession affected many countries, but despite the greater legacy of a command-and-control economy than in Russia’s case, China has now been a WTO member for a decade.

In Russia’s case, wavering within the political elite about the priority to be given to WTO membership played an important role in delaying progress. The twists and turns of the process are described in a brilliant essay by Anders Aaslund entitled Why Doesn’t Russia Join the WTO? in the April 2010 edition of the Washington Quarterly. The sudden and unexpected announcement in July 2010 that Russian intended to form a customs union with Belarus and Kazakhstan further complicated matters because it required the renegotiation of much of the report of the WTO Working Party on Russian accession.

EU’s agrifood sector and Russian WTO accession

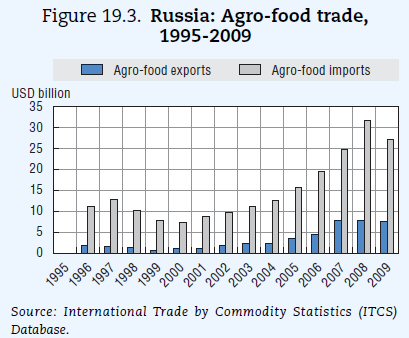

Russia is the EU’s second largest export market for agri-food products after the US, and the EU is Russia’s largest supplier, accounting for 38% of its imports in 2010. 80% of the EU’s exports to Russia are final goods, mainly fresh fruits and vegetables, cheese, frozen pigmeat and drinks. Russia has seen its agricultural imports explode in recent years, apart from the downturn in 2009. However, Russia is also a major exporter of grain, particularly wheat, and its policies towards grain exports helped to destabilise world grain markets in recent years.

Russia’s agricultural policy has become steadily more protectionist over time. Its percentage PSE increased from 18% in 1995-97 to 22% in 2008-10, thus exceeding the OECD average of 20%. Around two-thirds of this support derives from market price support, largely due to border protection. In addition, producers benefit from budget transfers in the form of subsidies on variable inputs and investments, while livestock producers have benefited given that domestic grain prices have been held below world prices.

WTO membership for Russia will bring important benefits for the EU’s agri-food industry through creating greater security of market access and possibly opening some additional markets. Market access issues include Russia’s somewhat arbitrary use of SPS measures, the future of Russia’s TRQs especially for meat imports, and the overall level of its trade-distorting support for its agriculture in future.

Russia’s use of SPS measures to restrict imports was seen most recently this summer when it restricted all imports of fresh vegetables from the EU27 countries because of the e.coli outbreak in Germany. The EU protested that the measures were excessive and disproportionate and not based on the SPS procedures that would apply under WTO rules.

The WTO Working Party wants to make sure that Russia’s SPS regime is transparent and non-protectionist. A difficulty is that the customs union (RU, BY and KZ) now has formal control of the SPS conditions regarding imports and in many cases the SPS regime is not yet defined as the authorities of the three countries must agree on this.

In two other key areas of import tariffs and domestic support, Liefert and colleagues report that Russia in its accession negotiations has been asking for bound commitments above the existing levels (a bound tariff or support amount is a maximum allowable level in the future). Russia’s current average agricultural import tariff is about 18%, up from 10% in 2000. However, Russia is negotiating for bound agricultural tariffs above actual applied tariffs. On domestic support, Russia has been asking for annual bound support of $9.5 billion, which compares to its 2007 actual support level of $5.7 billion,

The OECD reports that in late 2010, Russia’s position is to accede with a commitment on Total Aggregate Measurement of Support corresponding to $9 billion and maintain this level until 2012 (the end year of the current State Programme for Development of Agriculture). The commitment level would then decline to $4.4 billion between 2013 and 2017. Some negotiating parties want to see lower commitment levels from the beginning of Russia’s membership, based on the average level of trade-distorting support in recent years. Russia no longer proposes to schedule entitlements to export subsidies in agriculture.

Prospects

While accession terms such as those indicated might not do much to liberalise Russian trade and support policies immediately, EU suppliers would still benefit because bound levels would provide a cap on any future rises in tariffs and support. Also, there would be a forum where potentially troublesome SPS restrictions might be challenged if they were imposed.

However, even if bilateral negotiations have been successfully concluded with its major partners, there still remain a number of potential stumbling blocks in the way of Russia’s WTO accession. One is the continuing border dispute with Georgia which is already a WTO member. The other is the future of the Jackson-Vanik amendment in the US which denies MFN status to a country with a non-market economy deemed to restrict emigration. If these hurdles can be overcome and Russia does become a WTO member this year, it would be a major boost for a body sorely needing some good news given the Doha Round deadlock. .

This post has been authored by Alan Matthews