Trade data on trade between the EU and the UK for the first six months of this year confirm what economists had predicted would happen as a result of the additional trade barriers put in place once the transition period following Brexit came to an end on 31 December 2020. Even allowing for COVID-19 and temporary transitional effects, trade flows have reduced as companies have restructured their supply chains on either side of the English Channel.

What is less expected is that the impact on trade flows has not been symmetrical. According to an analysis by Jonathan Portes using UK trade statistics, UK exports of goods to the EU have now recovered roughly to their pre-COVID-19 levels. But imports from the EU are down substantially, by about 10% compared to two years ago, partly offset by an increase in imports from the rest of the world. Some of the fall in imports can be explained by an increase in imports before the end of the transition period as UK firms stockpiled goods in anticipation of Brexit-related disruption, but UK imports from the EU have yet to regain earlier levels.

Agri-food trade does not reflect this general trend. According to the latest July 2021 edition of Monitoring Agri-Food Trade, EU agri-food exports to the UK fell by 6% in the January-April 2021 period compared to the same period in 2020, but EU imports from the UK plummeted by 37%, both measured in value terms. Its worth noting that significant discrepancies between UK and EU trade figures for the same trade flows have emerged following Brexit, an issue which the Senior Statistician in the UK Office of National Statistics highlights in this blog post. However, I don’t think the issue highlighted in that blog post (differences in the way imports from non-EU countries subsequently exported to the EU are recorded) would be a significant factor in the livestock product trade statistics reported in this blog post.

In this post, I compare these trends for animal-source foods (or Products of Animal Origin, POAO as they are referred to in customs terminology). Amongst all food and drink products, POAO products were expected to be the most affected by Brexit because they face much higher non-tariff barrier trade costs. In addition to customs clearance costs that apply to all food and drink products, POAO products face additional trade requirements such as the need for health certificates, pre-notification of shipments, veterinary inspections on arrival, and the requirement that imports can only enter through approved Border Control Posts.

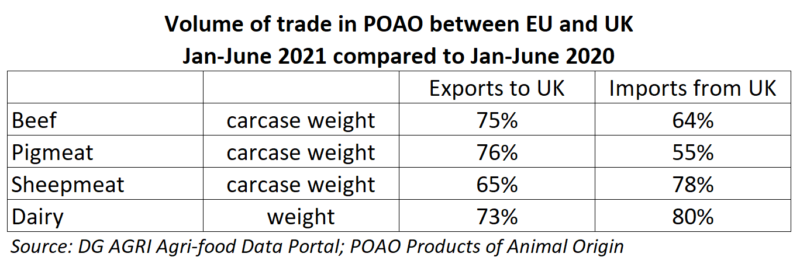

To eliminate impacts due to changes in price, in the following table I compare the volume of trade in both directions in the first six months of 2021 compared to the same period in 2020 for beef, pigmeat, sheepmeat and dairy products. In all cases there has been a dramatic reduction in trade. While the drop in imports from the UK has been roughly in line with the overall drop in the value of agri-food imports, especially for beef and pigmeat, the drop in exports to the UK has been much greater. Exports to the UK of POAO are running at only about 75% of their level last year (even lower in the case of sheepmeat).

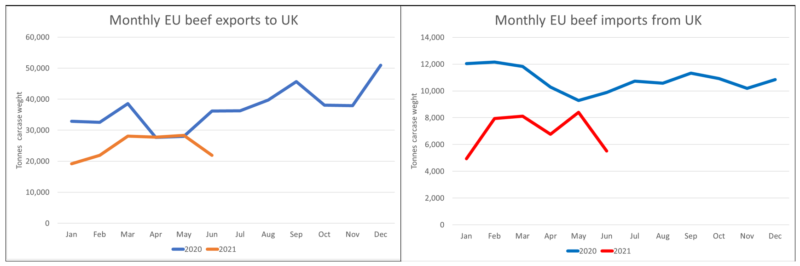

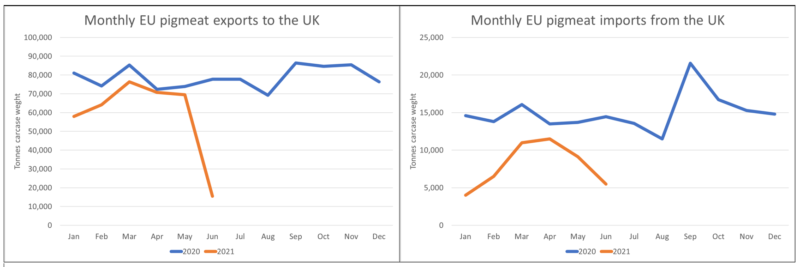

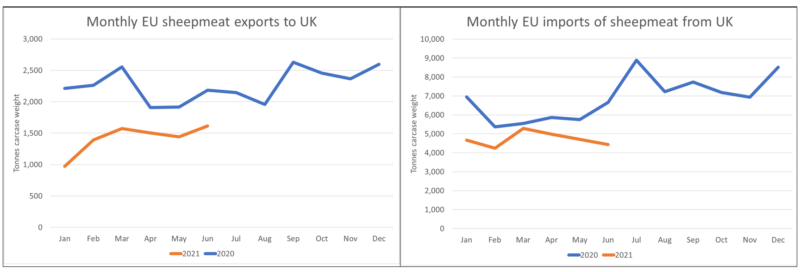

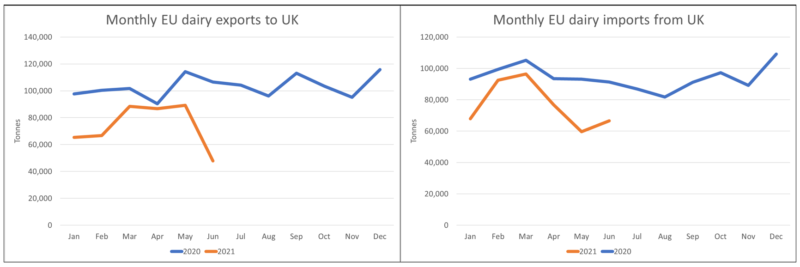

Looking at the monthly data shows considerable month-to-month volatility, suggesting that trade flows may still be influenced by temporary factors. In interpreting the following charts, take care to notice that the amounts traded, as reflected in the scale of the vertical axis, are very different between exports and imports for the same product and across products. The collapse in beef exports to the UK between December 2020 and January 2021 is quite remarkable and may reflect the influence of stockpiling mentioned previously. More recently, the dramatic falls in pigmeat and dairy exports to the UK in June are also highly unusual.

What makes these figures even more puzzling is that, while EU imports from Great Britain (note that different rules apply to Northern Ireland) have been subject to the full rigour of EU import controls since the beginning of the year, this is not the case for EU exports to Great Britain. The UK postponed the requirement that imports into Great Britain from the EU must be accompanied by the appropriate health certificate until 1 October 2021, except where the EU region of import is subject to safeguard measures (generally where there is an outbreak of some animal disease). POAO from EU under safeguard measures must already be accompanied by a health certificate and pre-notified on the UK’s Import of products, animals, food and feed system (IPAFFS).

In addition, until January 2022, imports from the EU do not need to enter Great Britain via a Border Control Post and are not subject to veterinary checks at the border.

Furthermore, the entry into force of measures that will prohibit the export of certain meat products and preparations from the EU to Great Britain has also been delayed until 1 October 2021. This covers products such as chilled mince meat and chilled meat preparations (including sausages, hamburgers and meatballs).

When these measures are introduced later and at the end of this year, a further hit to EU exports to Great Britain can be expected.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Update 24 August 2021. The reference to the blog post highlighting growing discrepancies between UK and EU trade statistics after Brexit was added.

Photo credit: PxFuel under a Creative Commons licence.

I don’t know whether this comment from Eurostat helps:

“As of January 2021 onwards, data on trade with the United Kingdom is based on a mixed concept. In application of the Withdrawal Agreement Protocol on Ireland / Northern Ireland, for trade with Northern Ireland the statistical concepts applicable are the same as those for trade between Member States while for trade with the United Kingdom (excluding Northern Ireland) the same statistical concepts are applicable as for trade with any other extra-EU partner country.

For these reasons data on trade with the United Kingdom are not fully comparable with data on trade with other extra-EU trade partners, and for reference periods before and after the end of 2020.”

https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2013/december/tradoc_151969.pdf

Thanks for this very helpful comment, Alan. As you highlight, the 2020 trade statistics between EU and UK are based on the Intrastat reporting system. From 1 Jan 2021, trade with Great Britain has been based on customs data while trade with Northern Ireland continues to be estimated based on Intrastat, hence the reference to the mixed concept in the quotation you cite. Customs data information would generally be considered more reliable, Eurostat itself recognises there are issues with the quality of the Intrastat data. Undoubtedly, the change in the way in which trade statistics are collected between 2020 and 2021 will have an impact on the comparison between the two years. Interestingly, we would expect with the end of the Brexit transition period that the quality of EU-UK trade statistics should improve. If this were to account for some of the observed decline in trade, it would suggest that trade with the UK under the Intrastat system was overestimated when we would normally expect that system to underestimate trade. There are definitely some puzzling features in the data which would require interviewing those in the trade to get to the bottom of.