It has long been recognised that greater price and income volatility would accompany the move to a more market-oriented Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Already in the run-up to the Fischler Mid-Term Review (MTR) in 2003 which led to the decoupling of direct payments, the Commission published a working document on risk management tools for agriculture, with a special focus on insurance, in 2001. The Council MTR agreement mandated the Commission to study specific measures to address risks, crises and natural disasters that agriculture may face. This led to a Communication from the Commission in 2005 on risk and crisis management in agriculture which discussed different instruments that could be implemented in the CAP. Some tentative steps were taken in the 2008 Health Check to encourage member states to give greater attention to this issue.

Yet farmers, processors and policy-makers have struggled to respond. Risk management instruments supported by the CAP up to 2013 were not very successful. Volatility was already an issue when the last CAP reform was being negotiated (the last trough in milk prices occurred in 2009, the year before the Commission launched its first ideas for the new CAP). In response, the Commission proposed to enlarge the scope for member state support for risk management tools by introducing a ‘risk management tool-kit’ as one of the possible options to be included in Rural Development Programmes funded under the CAP Pillar 2.

A new report coordinated by Isabel Bardají and Alberto Garrido of the Research Centre for the Management of Agricultural and Environmental Risks (CEIGRAM) at the Technical University of Madrid and commissioned by the European Parliament Policy Department on behalf of COMAGRI reviews the state of play of risk management in the 2014-2020 Rural Development Programmes submitted by member states/regions. However, although CAP support for agricultural risk management has increased, the share of CAP funds being spent on crisis and prevention measures continues to be very low, less than 2% of the Pillar II funds and 0.4% of the total 2014-2020 CAP budget. (Update 25 April 2016: This paragraph has been corrected to reflect the fact that the report was commissioned by the European Parliament Policy Department (which works for the EP Committees including COMAGRI and not the European Parliament Research Service (which works on behalf of EP members)).

The EP study acknowledges that few or no figures at all on risk management spending can be found in standard statistical sources, and that it is extremely difficult to collect information on the situation of risk management tools in the EU. One of the major contributions of the study is to collect information about government spending on the implementation of risk management tools in the agricultural sector in the 28 EU member states.

Given the low priority for this spending area, the study also examines possible future CAP developments related to risk management in order to deal more effectively with income uncertainties and market volatility. Here it updates the final report of the Income Stabilisation research project completed in 2008 which looked at the design and economic impact of risk management tools for European agriculture. In this post, I concentrate on the descriptive part, leaving the policy recommendations to another day.

What are risk management tools?

The EP study usefully begins with a typology of risk management tools.

Crop and livestock insurance, especially for single perils (hail, frost, illness) is the most widely developed because it is less susceptible to the plagues of any agricultural insurance system, namely, moral hazard, adverse selection and the systemic nature of many risks. Moral hazard refers to the fact that farmers may adopt more high-risk behaviour knowing that their losses are covered. Adverse selection refers to the possibility that only those farmers who are high-risk in the first place will seek insurance. Systemic risk is where the condition of independence of risks across individuals and risks no longer holds so that risk-pooling is no longer effective (for example, in the case of a drop in market prices which affects all farmers producing that commodity). Where these issues cannot be addressed, insurance will not be profitable. Even in situations where they are addressed, the cost of premiums may still be too high from a farmer’s point of view.

Income and revenue insurance has attracted increasing attention, particularly in the US and Canada. The advantage for the farmer is that it protects the whole farm income/revenue while crop/livestock insurance policies only hedge specific commodities and livestock. However, the data information needs of insurers if they are to adequately price such insurance policies are vastly greater.

Mutual funds combine the insurance idea of pooling risk across members with pooling risk over time through the long-term commitment of members. Mutual funds are based on the establishment of financial reserves, built up through participants’ contributions, which can be withdrawn by members in the event of severe income losses, according to predefined rules. Hence, a mutual fund can be seen as a form of organized, joint precautionary savings fund to be used to smooth incomes over time.

Savings accounts can be seen as a form of self-insurance, where a farmer pays into a special savings account in good years and withdraws deposits in case of need in later years. They provide a means of offsetting risk over time, but do not involve any risk pooling across farms or farmers.

Fiscal/tax measures can also provide some income stabilisation effect. If farmers are allowed to average out income across years, they can reduce their tax bills by compensating bad with good years.

Finally, ad hoc measures are ex-post measures where governments intervene usually following catastrophic losses such as flooding or a disease outbreak where animals must be culled.

Evolution of support for risk management under the CAP

The EP study draws a distinction between risk management measures supported under Pillar 1 of the CAP (fruit and vegetables, and wine), the Pillar 2 risk management toolkit, and state aids. An important finding highlighted in the study is that most member states focus their risk management on ex-post ad hoc payments devoted to crisis management funded through state aids. The CAP risk management toolkit is largely irrelevant for most member states.

The first possibility to support risk management under the CAP was the introduction of measures in the fruit and vegetables (F&V) and wine sectors in Pillar 1 under the reform of the regulations governing their support in 2007. This allowed the introduction of mechanisms of prevention and crisis management, including support to crop insurance or setting up mutual funds.

In 2008, the Health Check reform extended the possibility to support risk management instruments for all sectors through the use up to 10% of their national ceilings devoted to the single payment scheme in Pillar 1. According to Article 68 of the Regulation (EC) No 73/2009 this amount could be allocated to contributions to insurance premiums for crop and animal insurance or by way of mutual funds for animal and plant diseases and environmental incidents.

State aid is strictly controlled within the EU to avoid distortions of competition. Aid making good damage caused by natural disasters or exceptional circumstances has always been permitted. Other state aids could also be permitted provided they fulfilled the Community Guidelines for State Aids or fell within the Agricultural Block Exemption Regulation. Aids to make good damage caused by natural disasters as well as aids towards the payment of insurance premiums or contributions to mutual funds under conditions set out in the Guidelines were permitted under this Regulation.

In the 2013 CAP reform, the possibility to support risk management tools in the F&V and wine sectors was kept in the new Common Market Organisation. The Article 68 arrangements were moved out of Pillar 1 to become part of the risk management toolkit in Pillar 2, while a new income stabilisation tool was added.

Thus the risk management toolkit now has three tools:

• financial contributions to premiums for crop, animal and plant insurance against economic losses to farmers caused by adverse climatic events, animal or plant diseases, pest infestation, or an environmental incident;

• financial contributions to mutual funds to pay financial compensations to farmers, for economic losses caused by adverse climatic events or by the outbreak of an animal or plant disease or pest infestation or an environmental incident;

• an income stabilisation tool, in the form of financial contributions to mutual funds, providing compensation to farmers for a severe drop in their income.

In each case, the Regulation sets out conditions limiting the extent of support that can be provided. For example, in the case of the new income stabilisation tool, support can only be granted when the drop of income exceeds 30% of the average annual income of the individual farmer in the preceding three-year period (or an Olympic five year average) and payments shall compensate for less than 70% of the income lost in the year the producer becomes eligible to receive this assistance.

In addition, the Guidelines for State Aid to the agriculture and forestry sectors were updated. The new Guidelines maintain the exemptions for compensation for natural disasters, aid for the payment of insurance premiums and aid for financial contributions to mutual funds. The threshold for losses before farmers become eligible for support has been removed (incidentally, meaning that this state aid expenditure will have to be reported in the WTO Amber Box). The EP study also points out that, because all aids included in the CAP are compatible with the internal market by definition, it is now also open to a member state to provide support for the income stabilisation tool from its own funds if it wished to do so.

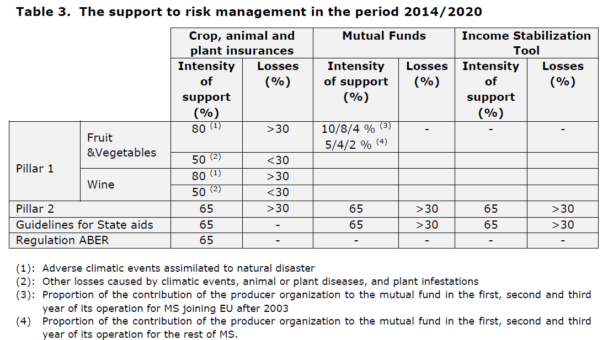

The table below, taken from the EP study, is a useful summary of the conditions attached to the various instruments in the period 2014-2020.

Source: Bardají and Garrido (2016)

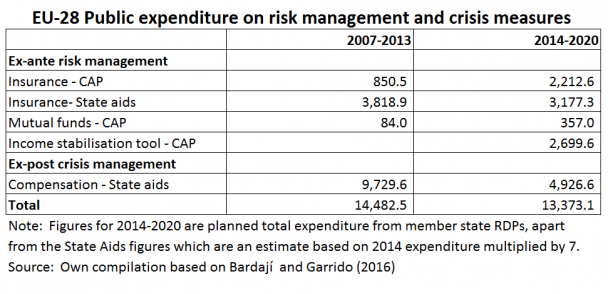

Source: Bardají and Garrido (2016)

Risk management in the CAP 2014-2020

According to the study, the risk management instruments supported by the CAP during 2007-2013 were not very successful. The use of risk management measures under Pillar 1 in the F&V and wine sectors has been very low. Provisions under Article 68 did get more attention, but only in a few member states and in connection mainly with crop/animal/plant insurance. In general, the implementation of mutual funds has been very limited.

The table below provides a summary of public expenditure both by the EU (under the CAP) and member states (largely under state aid rules, although the 2014-2020 data include member state co-financing of CAP RDP measures). The figures for state aids are speculative and are based on assuming that the level of 2014 expenditure will continue for the full programming period. Ex-post compensation payments, in particular, will be subject to the vagaries of natural and other disasters over the period.

Planned amounts reveal that Pillar 2 expenditure on risk management measures will be higher than previous Pillar 1 expenditure under Article 68. However, the take-up of the new income stabilisation tool is foreseen to be very limited, with only two EU member states and one region having decided to use it. As noted earlier, the share of CAP funds being spent on risk management remains negligible even if there has been a significant increase in percentage terms in the current programming period.

Conclusions

The EP study concludes that the new EU regulatory framework for public support for risk management tools provides a set of options, either through the CAP or State aid framework, with the potential to be adapted to specific conditions of each member state. However, it highlights two potential weaknesses.

One is that the inclusion of the risk management toolkit in Pillar 2 means that it is optional for member states/regions whether to make use of it or not, giving rise to an uneven implementation across the EU. I am not sure I see this necessarily as a weakness, as exposure to risk and attitudes to risk differ greatly across the member states.

The other is that the CAP measures in the RDPs are required to follow the strict criteria for eligibility for the WTO Green Box (which essentially means that only catastrophic (<30%) losses can be covered. However, member states can provide the same support as state aid without this restriction (implying that their expenditure will be classified as Amber Box support under WTO rules).

Three findings stand out from the careful data collection by the team behind the EP report.

• In the current MFF programming period, there has been a greater move to allocating public support to ex-ante risk management rather than ex-post crisis management, although arguably (as the EP report suggests) the balance should move even further in the former direction.

• The importance of state aid spending compared to CAP expenditure, something which may be encouraged by the laxer rules if spending is done under state aid rules rather than CAP rules.

• The low overall level of spending on risk management in the CAP budget as a whole.

It is, of course, argued that direct payments play a stabilising role in farm income and this is indeed the case. However, whether the current balance of instruments is the optimal one or not can be discussed. Whether the CAP should have a greater emphasis on risk management instruments in the future and, if so, how, is discussed at length in the second half of the EP study, and deserves another post.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit. Cumbria England flooding