This post has been revised to take account of the important role that the proposed ‘flexibility amount’ will play in influencing the scope that Member States will have to top up their minimum CAP ring-fenced amounts when preparing the CAP chapter of their National Plans. Its significance is such that it changes the tenor and conclusions of the original post. I am particularly grateful to Elsa Régnier for drawing this issue to my attention.

IDDRI, the Institut du développement durable et des relations internationals, has published a policy brief on the European Financial Framework 2028-2034: Key issues for the agricultural sector written by Elsa Régnier, Aurélie Catallo, and Pierre-Marie Aubert. This policy brief provides an excellent summary of key issues facing the co-legislator negotiators with respect to the agricultural sector following publication of the Commission’s MFF and CAP proposals in July. It is organised around six themes: three cross-cutting issues covering (1) governance, (2) the budget, and (3) the performance model, while three issues are more specific to the operational functioning of the CAP covering (4) direct payments (5), the environmental architecture, and (6) crisis and risk management.

I would encourage everyone to read the policy brief in full. In this post, I provide some reflections on what for me were the main messages under the first two headings of CAP governance and budget.

New governance for the agricultural sector

New decision-making bodies. For the authors, governance covers both the way in which decisions on the regulations that affect the agricultural sector will be made as well as the CAP’s own governance model. They note that, traditionally, CAP reforms have involved two negotiating spaces: the European Council (where decisions on budget allocations as well as financial rules pertaining to the CAP are made by unanimity), while more operational details were thrashed out by the AGRIFISH Council supported by the Special Committee on Agriculture, on the one side, and COMAGRI and its agricultural rapporteurs representing the Parliament, on the other side.

According to IDDRI, the new arrangements proposed by the Commission open up a new negotiating space, given that the CAP would become part of the new Single Fund (the National and Regional Partnership Fund). Many important elements of the CAP will now be decided in the negotiations on the Single Fund. The IDDRI brief gives a non-exhaustive list that covers the possible CAP interventions, co-financing rates, the share of coupled payments, the minimum and maximum amounts for degressive income support, measures subject to environmental and social conditionality, rules for drafting the CAP chapter of NRPPs, and the establishment of a “Unity Safety Net” replacing the agricultural reserve as well as support measures in the event of extreme climate events.

The IDDRI authors assume that this non-exhaustive list of provisions will not be negotiated by traditional agricultural policy actors. The Single Fund Regulation (COM(2025) 565 will be the responsibility of the General Affairs Council, supported by a working subgroup tracking the Single Fund. Also on the Parliament side, they suggest that a Committee other than COMAGRI will take the lead. They conclude that the reduced centrality of decision-making bodies traditionally tied to the agricultural sector could ultimately diminish the influence of the farm unions close to these institutions.

The IDDRI brief is right to note that the new proposals will alter the institutional decision-making dynamic although I question how substantive the changes will be. The proposed Single Fund Regulation does contain some very specific CAP-related elements that would previously have been included in the CAP regulations. Examples include Art. 57 on CAP Networks (now included as part of Title 7 on the Governance of the National Plan), Art. 62 on the control system for farm stewardship and Art. 70 on the Integrated Administration and Control System (now included as part of Title 8 on Management and Financial Rules for the National Plan), as well as Art. 42-48 covering POSEI interventions. It will be up to the Council and Parliament to decide in what way the specialist agricultural bodies will be involved in deliberations on these Articles.

But the key Art. 10 which sets out the minimum ring-fenced budget for the CAP and Art. 35 on the types of CAP interventions mainly address financial issues which would anyway have been included in the Negotiating Box to be decided by the European Council (ring-fencing and maximum ceilings for specific interventions, minimum rates of national contributions, maximum support rates). The specific rules regarding the design of these interventions are set out in the proposed CAP Regulation which will continue to be decided by the AGRIFISH Council and COMAGRI on behalf of the Parliament. While the new institutional structure may give rise to disputes over which Council working group or Parliament committee is responsible for specific elements of the proposals, the substantive changes in who gets to decide on the design of the principal CAP interventions may be more limited.

Governance of the CAP. The IDDRI brief also sees changes in the CAP’s own governance in the Commission proposals. It highlights the much greater flexibility Member States will have, not only in terms of the size of their CAP budget (see next point) but also in how to allocate it across the various CAP interventions (fewer ring-fenced amounts, no longer any barrier to shifting resources between what are Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 interventions in the current CAP as the Pillar structure would no longer exist). This gives rise to a concern about the coherence of the national CAP plans across the EU.

The proposals do give the Commission some stronger powers to issue national recommendations to Member States (the steering mechanism outlined in Art. 2 CAP Regulation), as well as to check that the CAP chapters in the national Plans address the environment and climate priority areas set out in the CAP Regulation (Art. 4) as well as the requirements set out in Art. 22 of the NRPF Regulation. More generally, with respect to the Plan as a whole, the Commission can request the inclusion of measures or the modification of measures proposed by a Member State (Art. 23 NRPF Regulation). It can also request Member States to contribute a higher or lower percentage of the total Plan expenditure to environmental and climate objectives. Also, it will now be the Council and not the Commission that will sign off on the submitted Plans. The IDDRI brief notes the danger that some of these guardrails will be removed during the negotiations on the legislation between Parliament and Council.

A shrinking CAP budget?

Scope for topping up the minimum ring-fenced budget for CAP income support. The IDDRI brief is rightly cautious on drawing conclusions about the size of the CAP budget in the next programming period compared to the current one, based on the Commission proposal. They note that the ring-fenced amount for CAP income support interventions in the National and Regional Partnership Fund is a minimum amount which can be topped up by individual Member States from the unearmarked money in the Fund, and that overall public support (EU plus national budgets) will also be influenced by changes in the rules around national contributions (the mirror image of EAFRD co-financing in the current CAP). Drawing on work by Schreiber and Ferrer (2025) for the Conference of Peripheral Maritime Regions, the authors note that the non-ring-fenced amounts will vary significantly between Member States.

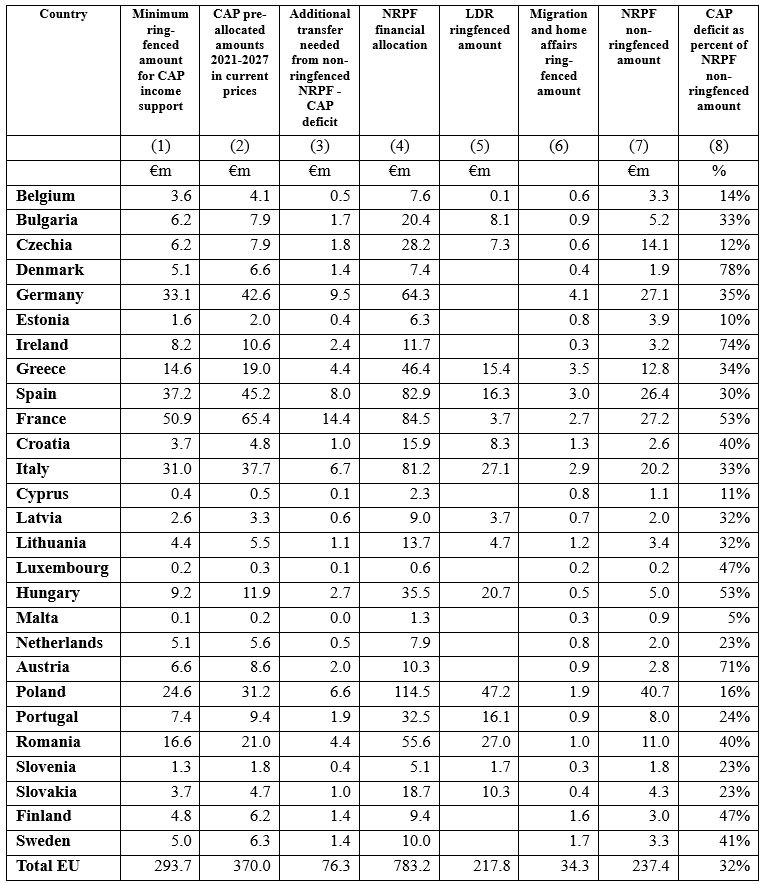

As the Commission has now published the national breakdown of the minimum ring-fenced CAP amounts, I have updated the Schreiber and Ferrer calculations in Table 1. The national minimum figures (column (1)) are calculated by the Commission by applying the national shares of CAP expenditure in 2027 to the overall ring-fenced amount of €293.7 billion in current prices for the CAP (there is a further €2 billion ring-fenced for fisheries income support in the NRPF Regulation but, as the Commission has not provided the national breakdown for this figure, it is not taken into consideration in the calculations in Table 1). Total CAP pre-allocated expenditure in current prices in the 2021-2027 programming period is €370.0 billion which is 26% greater.

Comparing the pre-allocated amounts in the EAGF and EAFRD to each country in 2021-2027 in column (2) of Table 1 with the minimum ring-fenced amounts, we obtain what each country would need to allocate to its CAP budget in 2028-2034 in order to maintain that budget at 2021-2027 levels in current prices. The additional transfer that would be required from the unearmarked part of the NRP Fund to hold the CAP budget constant in current prices in each Member State (column 3) we call the CAP deficit. This is also needed to cover the compulsory expenditure on CAP rural development interventions that are not included in the minimum ring-fenced amount.

The financial envelope set aside for each Member State in the NRP Fund is shown in column (4). This is the amount available to fund cohesion, agriculture, fisheries, social and defence mobility objectives, as well as the amounts allocated to migration and home affairs. It excludes the EU Facility and Interreg.

Of this amount, a total of €217.8 billion is reserved for cohesion spending in less developed regions, that is, those NUTS2 regions with a GDP per capita in purchasing power terms less than 75% of average EU-27 GDP per capita. Annex II of the NRPF Regulation sets out the allocation formula and the resulting national spending allocations for these regions (column (5)). As these amounts are ring-fenced, they are not available to transfer to the CAP. Not all countries contain less developed regions on this definition so the amounts are blank for those countries.

In addition, minimum spending amounts for migration and home affairs are required for each Member State according to the formula set out in Annex 1b to the NRPP Regulation. These are set out in Column 6.

By subtracting the minimum ring-fenced amount for the CAP, for less developed regions and for migration and home affaris from the NRPF financial allocation for each Member State, we can calculate the unearmarked amount which can be used to top up CAP spending, but which could also be allocated to any of the other Fund objectives (column (7). To provide a first assessment of the flexibility available to Member States, we can finally express the amount needed to transfer to the CAP budget to keep it constant at 2027 levels in current prices (column (3)) as a share of the non-ring-fenced amount (column (7). This percentage is shown in column (8).

Note: A further €2 billion will be ring-fenced for Fisheries support but the national allocations are not yet published so this ring-fencing is not considered in this table.

Sources: For explanation and sources, see text. LDR = Less developed region. The NRPF financial allocations are from the Commission, Fact Sheet on Member State Allocation. LRD minimum allocations from Annex II, NRPP Regulation. CAP amounts in 2021-2027 are taken from the Commission webpage on Budget Pre-allocations.

In interpreting the figures in column (8), we should recall that the CAP Regulation requires Member States to provide support to some interventions that are not included in the minimum ring-fenced amount which only covers CAP income support interventions. Support for AKIS, cooperation interventions (such as LEADER, EIP-AGRI or producer organisations), school schemes and POSEI will need to be provided in addition. I previously estimated that, on average for the EU, such interventions accounted for around 8% of CAP expenditure in the current programming period. These will require to be financed in any case from the unearmarked amounts.

Table 1 shows that the scope for CAP transfers varies greatly among Member States. The most constrained country is Denmark, which would need to allocate 78% of its unearmarked reserve to top up the CAP minimum ring-fenced amount to support its farmers at the 2021-2027 level. Ireland and Austria are also quite constrained as they would need to allocate between 71-74% of the unearmarked reserve to additional CAP spending. Doing so would squeeze the resources available for cohesion and social spending in transition and more developed regions not covered by the ring-fenced amount for less developed regions.

At the bottom of the rankings, countries like Malta, Cyprus, Estonia, Czechia and Poland would need to allocate less than 16% of their unearmarked amount as additional CAP transfers to ensure their farmers received at least the 2021-2027 level of support in the next period.

Whether a country is required to ring-fence some of its NRPF allocation for less developed regions or not can influence its scope for CAP transfers, but these countries are also favoured by the formula used to allocate NRPF General Allocation resources in Annex 1a to the Regulation. This includes an additional premium for a ‘regional prosperity gap’, defined as the share of its population living in NUTS3 regions with a GDP per capita in purchasing power standard less than 75% of the EU average (see my previous post for an explanation of this allocation formula). So it is primarily the outcome of the NRPF General Allocation formula that determines the scope for transferring additional NRPF resources to the CAP.

Taking account of the flexibility amount

However, this is not the end of the story. An additional constraint on the ability of Member States to transfer unearmarked resources to the CAP budget is the requirement on Member States to maintain a ‘flexibility amount’ within their NRP Plan allocation (Art. 14 NRPF Regulation). This would oblige Member States to set aside 25% of their NRPF financial allocation (excluding most of the minimum CAP ring-fenced amount, investment aids are not included) at the outset of the Plan period to meet unforeseen expenditure needs arising from crisis situations due to natural disasters (two-fifths of the amount) and to create a Mid-term Reserve (three-fifths of the amount). Crisis funds would be used for actions to address urgent and specific needs as a response to a crisis situation such as a major or regional natural disaster, including those affecting farmers, and foster repair and recovery in view of increasing resilience following a crisis. In case there is no call or only a partial call on the flexibility amount for this purpose, the amount reserved in this way can gradually be released for programming with the final tranche released for programming after June 2033.

There are several ways this flexibility amount can influence the size of the CAP budget. First, and most important, at the beginning of the Plan period, this flexibility amount will not be available to transfer to the CAP budget as it cannot be programmed for this purpose. It thus cannot be considered as part of the unearmarked resource, at least at the outset of the programming period. At the Mid-tern Review in 2031, any funds outstanding from the first one-fifth of the flexibility amount to fund natural disaster crisis payments will be added to the Mid-term Review reserve and at that point these funds become part of the unearmarked resource. This money would then become available to be programmed, with the final fifth held in reserve for crisis payments until June 2033.

In principle, the amounts released in this way could be allocated either to the CAP or to the other objectives of the Fund. However, it may be easier to ramp up investment projects which are typical of cohesion spending than it would be to increase CAP spending such as enrolment in agri-environment-climate actions. Also, governments may find it more justified to allocate the funds to worthwhile regional investment projects than to simply provide an unexpected transfer to area-based income support payments half-way through the Plan period.

The flexibility amount does not rule out the possibility that funds frozen in this way in the early part of the Plan period could ultimately be allocated to the CAP budget. But, taking a political economy perspective, the cohesion fund constituencies will argue that the flexibility amount has been taken out of ‘their’ allocation (recall that the CAP income support funds are exempt) and will have a strong expectation that any funds that become available for programing later in the Plan period should be spent supporting their objectives. At a minimum, the introduction of the flexibility amount would seem to stack the cards against the CAP receiving as much of a bonus from the transfer of the unearmarked NRPF resource as Table 1 suggests would be needed to maintain a constant CAP budget in current prices.

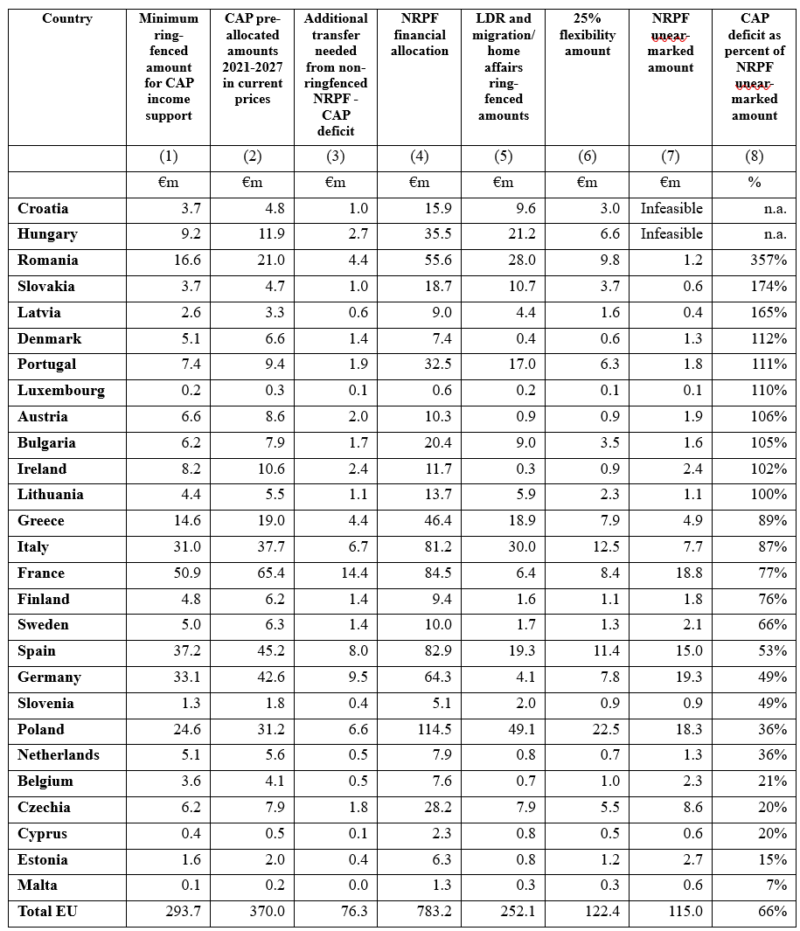

To assess the impact of the flexibility amount, we redo Table 1 assuming that this amount will not be available to programme as part of the CAP budget at the outset of the Plan. Table 2 gives the revised figures, where column (6) shows the calculated flexibility amount for each country. Note that this is slightly underestimated as I have subtracted the entire minimum CAP income support amount from a country’s NRPF financial allocation whereas investment supports to farmers and foresters should be excluded. What the allocation will be to investment supports will not be known until the National Plans are approved so we cannot take account of them here.

While the CAP income support amounts are specifically exempted from the 25% flexibility deduction this is not the case for the amounts ring-fenced for less developed regions and migration and home affairs. This might suggest it would be reasonable to reduce the LDR and migration/home affairs ring-fencing also by 25% to avoid double-counting these amounts when calculating the unearmarked resources potentially available to top up the CAP budget.

But there is an obligation on Member States to allocate at least these minimum LDR amounts and migration/home affairs amounts over the course of the Plan. If some of the flexibility amount is required to compensate for natural disasters, this does not let Member States off the hook and to reduce the amount they must allocate to these other ring-fenced amounts. Thus, de facto even if it is not explicit, the ring-fenced LDR and migration/home affairs amounts will have to be programmed sooner or later.

We thus define the revised estimate of unearmarked NRPF resources at the outset of the Plan as each country’s financial allocation, less the minimum CAP ring-fenced amount, less the minimum LDR ring-fenced amount, less the ring-fenced migration and home affairs amount (assuming all of these must be programmed in full at the outset), less the 25% that must be allocated to the flexibility amount (column (7). The required transfer to top up the minimum CAP ring-fenced budget to maintain CAP spending at 2021-2027 levels (column (3)) is then expressed as a percentage of the revised unearmarked NRPF allocation (column (7) in column (8).

Note: An additional €2 billion will be ring-fenced for Fisheries support but as the Member State allocations are not yet available, this Fisheries support is not considered in this table.

Source: See text and sources to Table 1. LDR = less developed region. The flexibility amount is calculated as 25% of the difference between a country’s NRPF financial allocation and its minimum CAP ring-fenced amount for income support. This slightly underestimates the flexibility amount as CAP investment aids to farmers and foresters should be excluded from the CAP income support amounts that are deducted, but these allocations will not be known until the approval of the CAP chapters in the National Plans.

Three groups of countries can be highlighted in Table 2. To more clearly identify these groups, I have ranked countries by the size of the percentage in the final column (8). The first group consists of two countries, Croatia and Hungary, for whom the maths of the legal requirements are infeasible. For both countries, it will not be possible to programme the minimum CAP ring-fenced amount, the minimum LDR ring-fenced amount, the minimum amount for migration/home affairs, and as well set aside 25% of their non-CAP NRPF financial allocation as a flexibility amount. The sum of these four amounts exceeds their total NRPF financial allocation. What they would have to do is to reduce their initial programming of their CAP, LDR or migration/home affairs amounts to below the minimum, hope that they do not suffer natural disasters that would eat up the flexibility amount, and then use the flexibility amount resources as they become available to reprogramme the missing amounts for either the CAP, their less developed regions, or migration/home affairs. But legal obligations should not depend on hope for an outcome.

The second group of countries in Table 2 consists of 10 of the 27 countries that now have a percentage greater than 100% in column (8). These are countries where the amounts required to top up their minimum CAP ring-fenced amounts exceed what might be available as unearmarked resources in their NRP Plans. These countries, when they present their Plans, will inevitably have a smaller CAP budget from EU resources to programme for the 2028-2034 period than what they will have in 2021-2027. It is possible that, over the course of the Plan, some of the frozen flexibility amount could be redirected towards the CAP (see later paragraph). In other words, we would move back towards a situation as characterised by Table 1. However, I have given reasons why this might not happen. In any case, it would continue a situation of uncertainty for farmers in these countries as to what they can expect in the form of CAP support for several years into the programming period, which is unlikely to be politically acceptable.

The third group of countries are those that will still have the possibility to transfer sufficient amounts from the unearmarked resource to ensure that their CAP budgets remain constant in current prices at 2027 levels. However, the percentages are all higher than in Table 1. For example, France needs to find €14.4 billion to add to its minimum ring-fenced amount of €50.9 billion to enable it to maintain the EU CAP budget at the same level as in 2021-2027. Without considering the flexibility amount, this would require a transfer of 53% of its unearmarked amount to the CAP (Table 1) which might be seen as feasible. But taking account of the need to set aside the unprogrammed flexibility amount, this percentage increases to 77%. This would leave very little for the Plan to allocate to cohesion funding in transition and more developed regions and other objectives in the initial programming, even if all of the frozen flexibility amount were subsequently to be redirected back to these other objectives later in the programming period in the absence of major natural disasters.

In a further development, Commission President von der Leyen in a letter to the Council and Parliament Presidents confirmed that the Commission intends to open the possibility for Member States to use up to two-thirds of the flexibility amount reserved for the Mid-term Review for programming either for CAP income support or for measures dedicated to rural areas. This will make it easier for Member States to transfer funding to the CAP. I estimate the potential increase in CAP funding in this post.

National contribution rates. It is one thing to identify the scope for transferring additional resources to the CAP budget within the NRPF allocation; it is another thing whether Member States will have an incentive to do this. From this perspective, the rules on national contribution rates can influence both the incentive to make these transfers as well as the total size of public (both EU and national) support to farmers in the next programming period.

The IDDRI brief notes that the rules for national co-financing rates have become stricter in the new proposals. On the one hand, this could attract additional national resources in addition to the allocation from the Union budget to support farmers. On the other hand, because the national contribution rates are highly differentiated across CAP interventions, this is likely to distort the choice that Member States make about which CAP interventions to include in their CAP Plans.

The general rates for national co-financing contributions for any intervention in the NRP Plan are differentiated by type of region. The rates are (a) 15% for less developed regions; (b) 40% for transition regions; (c) 60% for more developed regions (Art. 20(1) NRPF Regulation).

For CAP interventions, there are three layers of national contribution rates:

- No national contribution is required for four CAP interventions (a) degressive area-based income support (b) coupled income support, (c) crop-specific payment for cotton, and (g) support for small farmers (Art. 20(4) NRPF Regulation). No additional national financing can be provided for these interventions.

- For all other CAP interventions, the minimum national contribution rate shall be at least 30% of the estimated cost (Art. 35 (4)). Higher national contribution rates are allowed.

- However, these 0% and 30% minimum rates only apply to expenditure up to the minimum ring-fenced for CAP income support for each Member State. If a Member State wishes to top up this minimum amount by transferring unearmarked resources from the NRP Fund, the general regional rates apply. For CAP expenditure in NUTS2 less developed regions, this will be a minimum of 15%, in more developed NUTS2 regions it will be 60% (Art. 20(4)).

The incentive for Member States with limited fiscal resources will be, as the IDDRI authors point out, to prioritise the CAP interventions with no requirement for national co-financing, which are the area-based income payments and coupled payments (though it both cases there are maximum expenditure ceilings established in the proposed NRPF Regulation which will limit the extent to which this can happen).

On the other hand, for a Member State that wanted to give additional support to its farmers, a Member State can make a larger national co-financing contribution to the minimum CAP ring-fenced amount. Take Ireland as an example where the minimum ring-fenced allocation for CAP income support measures is €8.2 billion over the programming period. We assume that all of Ireland would be designated as a more developed region with a minimum national contribution rate of 60%, even if it is likely that one of its two NUTS2 regions would be in the transition category with a minimum national contribution rate of 40%, but let us leave this additional wrinkle to one side in this discussion.

Suppose for the sake of illustration that Ireland divides its minimum ring-fenced amount equally between the 0% national co-financing interventions and the remaining CAP income support interventions where a minimum of 30% national co-financing is required. But this is a minimum. Ireland could well decide to co-finance these remaining interventions at, say, a 50% rate if it wished to provide additional support to its farmers from its national resources.

Alternatively, Ireland might decide to transfer some of its unearmarked NRPF resources to increase its CAP budget. In this case it would have to accompany these resources with the mandatory 60% national co-financing contribution. This is not in itself a disincentive to making the transfer to the CAP. If Ireland decided to use these NRPF resources for other NRPF objectives such as cohesion or social spending, it would also have to contribute this additional 60% from national resources. But the example illustrates that the allocation problem for the CAP budget has become more complex under the proposed new arrangements.

There are, in any case, the mandatory CAP interventions (AKIS, cooperation, POSEI, school schemes) which are outside the CAP income support category and which must be funded from the non-ring-fenced NRPF amount, together with the appropriate regional national co-financing contribution.

Countries that wish to increase their support to farmers beyond the ring-fenced minimum, but are net contributors at the margin to the NRPF budget (that is, pay in a higher amount based on the GNI contribution key to this Fund than the resources they are allocated from the Fund), have a big incentive to cut the size of the NRPF budget and to pay their support to farmers through an increased national contribution. In this way, they can support their own farmers without at the same time having to contribute to the support of farmers in other EU countries. The Netherlands, where the Minister for Agriculture is a member of the Farmer-Citizen (BBB) party and keen to increase support to farmers, might be one country expected to make this argument.

Environmental, climate and social tracking indicators. There are other constraints on shifting resources within the NRP Fund which should be kept in mind arising from the requirements for environment and climate tracking and a minimum amount for social objectives. The proposed Budget Performance and Tracking Regulation would introduce climate and environmental tracking as a horizontal obligation for EU expenditure. It would establish an overall target that at least 35% of the overall MFF budget should be spent on climate and environmental objectives. Annex III sets a minimum allocation of 43% of the financial envelope of NRP Plans for combined climate and environmental goals (Art. 4). As the EU coefficients used to track the environment and climate significance of CAP interventions are generous, this could incentivise Member States to prioritise CAP interventions if they have difficulty otherwise in demonstrating that they have met this target.

The NRPF Regulation sets the objective that at least 14% of the NRPF financial envelope as well as the amount of loan support for Member States for implementation of their Plans should be dedicated to meeting the Union’s social objectives, again using EU coefficients attached to each intervention (Art. 10(5) NRPF Regulation). However, the minimum ring-fenced amount for CAP income support interventions is excluded from this requirement so it will not have any influence on how Member States allocate their NRPF resources between the CAP and other objectives.

Longer uncertainty about overall size of the CAP budget. An issue underplayed in the IDDRI brief is that the proposed new arrangements imply there will be uncertainty about the future size of the CAP budget for farmers for a much longer time than in previous CAP reforms. In the current programming period, negotiations on the CAP regulations did not seriously begin until the CAP budget in the MFF was known. But the CAP budget was known already in July 2020 when the European Council MFF conclusions were agreed, even if it was not until December 2020 after further negotiations that the Parliament also gave its consent to the MFF as a whole.

Under the new arrangements, the CAP budget will no longer be decided when the MFF negotiations are concluded. This will simply be the start signal for the finalisation of the NRP Plans, although one assumes that a lot of preparatory work will have been done prior to that. But as the IDDRI paper recognises, until the national Plans are finally submitted and approved, including commitments to transfers within the NRP Fund as well as associated national co-financing contributions, the overall CAP budget will remain uncertain. This is one of the undesirable consequences of the proposed new arrangements from a farmer’s perspective.

Conclusions

In this post, I have reflected on two of the six issues – governance and budget – that the IDDRI authors raise in their thoughtful policy brief. Their discussion of the other topics such as the performance framework, direct payments, the green architecture and crisis payments is also well worth reading.

The authors suggest that the proposed MFF architecture will open up new negotiating spaces which could diminish the role of the farm unions close to the traditional negotiating partners of the AGRIFISH Council and COMAGRI and its rapporteurs. While the inclusion of CAP-related issues in the main NRPF Regulation is challenging the traditional negotiating structures, I am less persuaded that this will result in substantive changes. Many of the CAP-related issues in the NRPF Regulation are finance-related which we would expect would be addressed in the European Council’s MFF conclusions. Here they are included in a legislative act which will be decided under the ordinary legislative procedure (co-decision).

We must wait to see how far the first iteration of the Negotiating Box for the MFF conclusions which will be presented by the Danish Presidency at the December 2025 meeting of the European Council will go in making decisions on these issues. For the more technical Articles dealing with the CAP, I would not be surprised if the main Council and Parliament bodies that will be responsible for the various Regulations will defer to the traditional agricultural bodies who will in any case be responsible for the CAP and Amending CMO Regulations.

The IDDRI brief gives a very clear exposition of the controversies that have erupted around the likely CAP budget. My contribution in this blog post has been to show that Member States have very different scope for making additional transfers from the unearmarked component of the NRP Fund to top up the minimum ring-fenced budget for CAP income support interventions. This is particularly the case if we allow for the impact of reserving the flexibility amount when drawing up the National Plans. The flexibility amount cannot immediately be programmed for either CAP or other objectives of the NRPF, but must be reserved to address potential natural disasters at least until well into the programming period. It means that around half of all Member States will have less EU CAP money to programme at the beginning of the programming period than they will have in 2027. It is possible that their CAP budgets could be increased over the Plan period if the flexibility amount is not used and becomes available for reprogramming but I cannot see that being an acceptable outcome for the countries involved.

This finding qualifies the conclusion in my previous post that there is a good chance that the level of CAP support would be maintained in current prices if the Commission’s MFF proposal were approved as it stands. This assessment may still stand for the EU as whole, but not necessarily for each Member State. Based on the results shown in Table 1 and particularly Table 2, some will see a fall in their CAP support from the EU budget, while others could well see an increase.

As a partial alternative to transferring funds from within the NRP Fund, Member States are at liberty to increase their minimum national co-financing contributions to provide additional support to their farmers. For many Member States with limited fiscal space, this may not be feasible, but for those Member States that would be net contributors to the NRP Fund, a smaller Fund but higher national co-financing contributions would be an attractive option.

The overall size of the Commission’s MFF proposal is ambitious. We already hear rumblings that several Member States consider it is far too big. But as I have emphasised in a previous post, the Commission proposal maintains the spending allocation for traditional priorities in current prices, with all of the increase going to non-traditional priorities and repayment of the NGEU loan.

If the overall amount is reduced, for farmers the important issue will be whether the reductions are made in the non-traditional priorities (mainly financed from the European Competitiveness Fund) or in the traditional priorities (mainly financed from the NRP Fund).

The agricultural stakeholders insist that there should be a stand-alone CAP in the MFF with its own budget. But I would see the prospects of increasing that budget beyond the amount set aside as ring-fenced for CAP income support as limited. If that hypothesis is correct, then insisting on a stand-alone budget for farmers would mean foregoing the possibility of making transfers from the unearmarked element of the NRP Fund. A stand-alone CAP budget could end up leading to a smaller CAP budget than is possible with the MFF architecture proposed by the Commission.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit: Cattle grazing, Hornsherred, Denmark, own photo.

Update 15 October 2025. I added Table 2 and the accompanying text illustrating how taking into account the impact of the flexibility amount will reduce the scope for transferring additional resources from within the NRP Fund to the CAP.

Update 27 January 2026. I recalculated Tables 1 and 2 to make the comparison more specifically between the minimum ring-fenced amount for CAP income support for 2028-2034 and the actual pre-allocated amounts to countries under the two CAP funds for 2021-2027 in order to calculate the so-called CAP deficit. I have corrected the flexibility amounts to include migration and home affairs as well as the general allocation in the 25% calculation. I have also highlighted the relaxation in the use of the flexibility amount proposed by the Commission in January 2026.