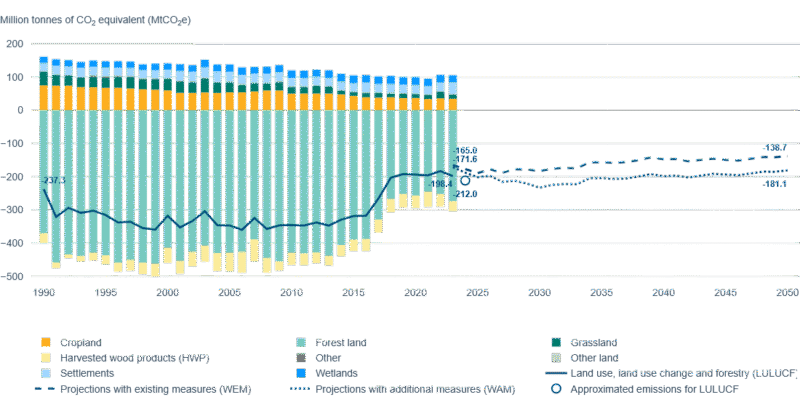

The EEA recently published updated projections for LULUCF emissions and removals by Member State to 2030 and 2050. It is not good news. Although the fall in the LULUCF sink appears to have been halted over the past six years, the EU27 net sink in 2023 was just 198MtCO2e and estimated at 212MtCO2e in 2024. This compares to the 2016-2018 average of 268MtCO2e and the 2030 target of 310MtCO2e set in the LULUCF Regulation (Figure 1).

Source: EEA, 2025.

The projections show that, with existing measures (the WEM scenario), the EU27 net sink is projected to be 183Mt CO2e in 2030 (all subsequent figures are in CO2e units). This does not necessarily imply a further fall in removals, as the base year removals for the projections in 2023 and 2024 are lower in the projections than in the inventory figures (165Mt and 172Mt, respectively). These differences reflect the frequent revisions in the LULUCF inventory as new information becomes available. With additional measures (the WAM scenario), net removals could reach 233Mt, but this figure would still be well below the 2030 LULUCF target.

The overall target in the European Climate Law is for a net 55% reduction in emissions compared to the 1990 baseline. To reach this target, the LULUCF contribution is capped at removals of 225Mt. If removals surpass this level in 2030, the result would be a slightly higher overall reduction than the net 55% target. The WAM scenario if fully implemented would allow this over-arching target in the Climate Law to be met.

Member State targets

Member States have a ‘no debit’ commitment for the five-year period 2021-2025, requiring that cumulative ‘accounted’ emissions from land use are compensated for by at least an equivalent amount of cumulative ‘accounted’ removals. Accounted emissions and removals for forest land are measured against Forest Management Reference Levels. The intention was to avoid crediting removals that are simply due to age-class dynamics or past management decisions, ensuring that only additional mitigation efforts count. Other deviations from simple net accounting include baseline accounting for cropland/grassland (relative to average emissions in the period 2005-2009), the voluntary accounting for wetlands also using baseline accounting if included, and the exclusion of natural disturbance emissions above a background level.

From 2026 onwards, the Regulation shifts from ‘no debit’ to binding national targets based on reported net removals. Each Member State has a binding national target for 2030, derived from the EU-wide target for a sink of 310Mt. These national targets are translated into a five-year carbon budget for the period 2026-2030 with annual ceilings, representing a cumulative net removals budget for the period. The Commission will check whether the cumulative net removals reported by each Member State meet or exceed their allocated budget.

To avoid back-loading increased removals into the final year, any exceedances above the annual ceilings in the period 2026-2029, after taking flexibilities into account, will be added to the 2030 inventory emissions figure, multiplied by a factor of 1.08. The Commission will assess compliance with the no-debit commitment for 2025 in 2027 and with the 2030 target in 2032.

The Commission will assess the progress of Member States towards their 2030 target in the second compliance period annually. If it finds that progress is insufficient, Member States must submit a corrective action plan. The Commission will assess the robustness of that plan and can issue an opinion. The Member State must publicly justify any decision not to address that opinion or a substantial part thereof.

Flexibilities

The revised LULUCF Regulation provides for several flexibilities to help Member States meet their targets, in addition to the exclusion of excessive natural disturbance emissions under certain conditions. There is a cross-sectoral ‘general flexibility’ whereby Member States can compensate deficits in their LULUCF accounts with surpluses in the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) sector, and vice versa.

Intra-EU trading of LULUCF credits is also possible, whereby countries with strong sinks can support those with deficits by transferring surplus credits. It is also possible for the deficit country to finance a greenhouse gas mitigation project in another country and to claim the credit, provided that double counting is avoided and traceability is ensured.

Finally, there are conditional flexibilities that can only be used if the EU as a whole meets its LULUCF target in each compliance period. There is a forest flexibility available in the period 2021-2025 that would allow Member States with structurally declining forest sinks (e.g. due to age-class dynamics) to generate limited additional credits. Member States can compensate excess accounted emissions from forest land provided they include measures to ensure conservation or the increase in forest sinks in their long-term strategies under the Governance Regulation, or they provide evidence of natural disturbances and plan measures to prevent or mitigate similar events in the future.

There is also a managed land flexibility for the 2026-2030 period that applies to cropland/grassland accounting to address excess net emissions due to natural disturbances, long-term impacts of climate change or an exceptionally high proportion of organic soils.

These flexibilities will be applied for the first time during the compliance check in 2027 against Member States’ commitments, based on the GHG inventory data for the period 2021-2025.

Towards a cliff edge in 2021-2025?

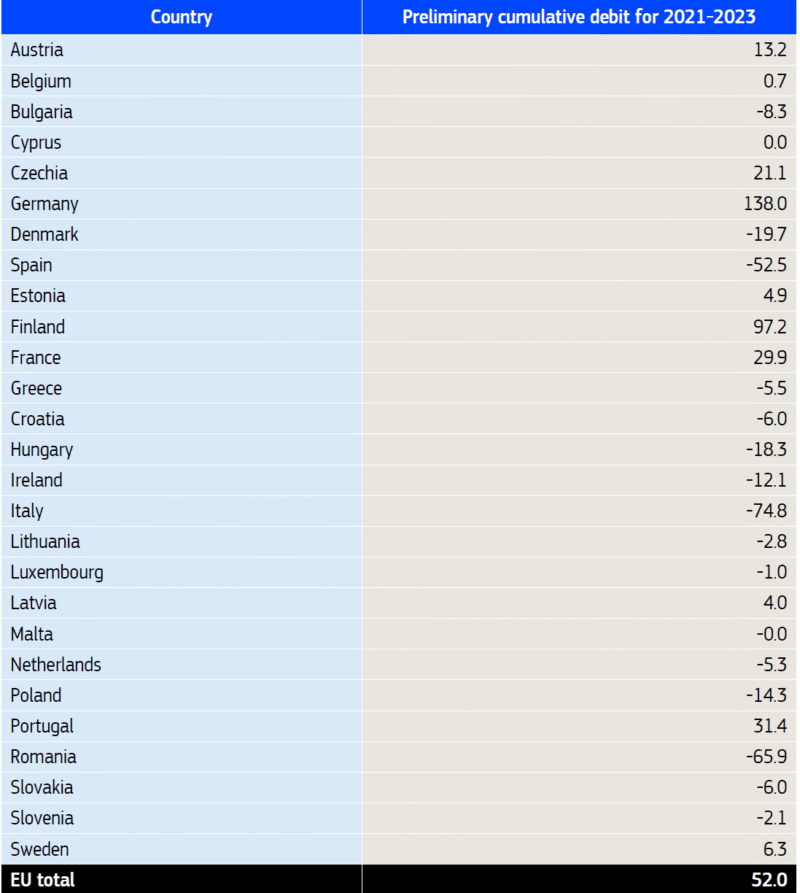

The Commission made an assessment in its 2025 Climate Action Progress Report of the status of each Member State with respect to the ‘no debit’ rule for the first three years of the first compliance period 2021-2023 (Table 1). It notes that this is an approximate estimate of the status of a Member State’s trend towards compliance with its ‘no debit’ commitment. The table shows a preliminary cumulative debit for the EU for the three-year period of 52Mt (note that the positive numbers in the table refer to accounting debits, and the negative numbers to accounting credits). Countries should have a zero or negative balance for the whole period to meet the ‘no debit’ target.

Source: Commission, Climate Action Progress Report 2025.

The table shows that 16 countries are on track to meet their ‘no debit’ commitment in the 2021-2025 compliance period while 11 countries are not likely to do so on current trends. This does not necessarily mean that these countries will be in breach of their target commitment as this will depend on the extent to which they make use of flexibilities.

If the cumulative debit persists for the full compliance period, the conditional flexibility mechanisms would not be accessible. But individual countries could still achieve compliance making use of the general flexibility (reallocating surplus ESR credits), through trading by purchasing from surplus countries, or through claiming natural disturbance exceptions. Member States who transfer surplus credits to another Member State are obliged to inform the Commission and to make the information public in an easily accessible form. They should also use the revenue to tackle climate change in the Union or in third countries.

To date, I am not aware that any trades in LULUCF credits have been reported. But with the compliance year 2027 fast approaching, and a likely overall shortage of surplus credits, Member States likely to be in trouble may want to start thinking about bilateral deals. But such bilateral deals are politically sensitive. They are open to the criticism that they outsource responsibility for reducing net emissions and that the money paid to the supplier country could have been used to strengthen the incentives for domestic action at home.

What happens if a Member State fails to reach its LULUCF targets?

The LULUCF Regulation does not prescribe any penalties or sanctions if a Member State fails to achieve its targets in either compliance period. However, Article 9(2) of the revised Effort Sharing Regulation (‘Compliance check’) requires that, if a Member State fails to meet its LULUCF ‘no debit’ target in the 2021-2025 period, then the excess will be deducted from that Member State’s annual emission allocations under the ESR for the relevant years (alternatively, we can interpret this as a compulsory transfer of ESR allocations to the LULUCF sector). This will make it more difficult for that Member State to show that it has met its annual national ESR targets in that period, and is thus an indirect sanction for failure to meet its ‘no debit’ obligation.

Recall that, unlike the LULUCF Regulation where compliance is determined over five-year periods, the ESR Regulation sets annual ceilings for each country’s emission allocations. The ESR Regulation Article 9(1) determines that compliance will be assessed in 2027 and 2032, as for the LULUCF Regulation. The ESR assessment in 2027 will determine for each year in the 2021-2025 period whether a country’s reviewed greenhouse gas emissions exceeded its annual emissions allocation, taking into account any deduction from its allocation due to LULUCF exceedances in that year under Article 9(2).

Furthermore, there is a penalty in the ESR Regulation whereby, if a Member State (taking into account the flexibilities that are available in the ESR Regulation) nonetheless still exceeds its annual allocation in any year between 2021 and 2030, then its greenhouse gas emission figures for the following year will be increased by 1.08 times the excess. Note that this can lead to a cumulative penalty in that, if this additional excess in turn leads to non-compliance in the following year, then the excess in the following year will also be penalised by multiplying by 1.08 when added to the following year’s GHG emissions.

This means that, for the 2021-2025 period assessed in 2027, there is an indirect penalty for countries that fail to meet their ‘no debit’ LULUCF target in this period. Although there are no annual LULUCF targets during this period, it seems that the Central Administrator will adjust the ESR annual emission allocation for each year in which there is a LULUCF deficit, but only for those countries that are in deficit for the entire period 2021-2025. If this then results in that country failing to meet its ESR target in that year, the penalty mechanism will apply in the ESR sector.

Neither the LULUCF nor the ESR Regulations provide for a similar mechanism for the 2026-2030 period. As noted previously, the governance mechanism in the LULUCF Regulation (Article 13c) seeks to prevent back-loading in this budget period by penalising the 2030 LULUCF accounts by adding 1.08 times the excess of the reported LULUCF net emissions over the annual limits to be set by the Commission for each country for the 2026-2029 years. But there is no automatic transfer of any excess over a country’s budget for the 2026-2030 period to the ESR account, nor is there provision to carry that excess forward into the following budget period. However, it is possible these issues may be addressed in the negotiations on the next revision of the LULUCF Regulation in connection with allocating national responsibilities to meet the 2040 climate target.

The infringement procedure

Failure to meet the LULUCF targets would, however, be a breach of EU obligations. The absence of a specific penalty clause in the LULUCF Regulation does not mean there are no consequences; it simply means the general enforcement mechanism of the EU legal order applies. The primary enforcement route is the general infringement procedure under the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which is not automatic and involves a political and legal process.

It is probable that the first preference of the Commission would be to request the non-compliant Member State to submit a detailed and credible corrective action plan (as we have seen, such plans are specifically provided for in the second compliance period even earlier in the compliance period if it is clear that the annual targets in the 2026-2029 period are being missed). If the Member State is non-cooperative, fails to submit a satisfactory plan, or fails to implement its own plan, then the Commission may initiate formal proceedings.

Infringement proceedings are lengthy with considerable Commission discretion along the way. First, the Commission sends a formal letter to the Member State, outlining the legal basis for the breach and giving it a deadline (usually two months) to respond and rectify the situation. If the Commission is not satisfied with the response, it issues a “reasoned opinion,” which is a formal legal analysis confirming the breach and setting a final deadline for compliance (e.g., by taking the necessary domestic measures to make up for the shortfall). If the Member State still does not comply, the Commission can refer the case to the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU).

The CJEU will rule on whether the Member State has failed to fulfil its obligations under the LULUCF Regulation. A ruling against the Member State is highly likely if the facts of non-compliance are clear. If the Member State still does not comply with the CJEU’s initial ruling, the Commission can bring a second case before the Court, this time requesting financial penalties.

These are not specified in the LULUCF Regulation but are calculated by the Commission based on the seriousness, duration, and “nudge” effect needed. They can take the form either of a lump sum (a one-off fine for the period of non-compliance up to the point of the second judgment) or a recurring fine (e.g., daily or semi-annual) that continues to be paid until the Member State achieves compliance. This process mirrors enforcement in other environmental sectors (e.g., air quality directives, habitats directive) where specific penalties are not written into the law but are imposed via the TFEU infringement route.

Conclusions

Overall in the EU, removals in the LULUCF sector have decreased in the past 10 years, as a result of climate change and natural disturbance impacts on forests, increased harvest of wood, as well as lower sequestration of carbon by ageing forests. More recent data suggest some stabilisation in the net LULUCF sink albeit at a lower level than in the past. Nonetheless, recent data and projections released by the Commission and the EEA suggest that the targets in the LULUCF Regulation for the two compliance periods 2021-2025 and 2026-2030 including the 2030 target will not be met. The EEA projections show that much stronger measures to expand and protect sinks will be needed if the EU is to reach the 310Mt target by 2030.

The Commission, in its 2024 review of the operation of the LULUCF Regulation, noted that very few Member States had set out a concrete pathway to meet their national net removal targets in their updated National Energy and Climate Plans, nor had they identified sufficient action to assist farmers, foresters and other stakeholders in building sustainable business models in line with these targets.

The lack of detailed pathways in Member States’ updated National Energy and Climate Plans to address the gaps to target suggests they are sleepwalking towards a cliff edge that may lead to unpleasant consequences. The Commission assessed the LULUCF actions in the final submitted NECPs as follows:

“…several Member States have stepped up their ambition and have provided more concrete pathways to meet their 2030 target with additional policies in the land sector. 9 Member States (up from 5 in the draft plans) now project to reach their LULUCF targets… However, most of the plans lack sufficient details on the actions needed to reach the targets, and a quantification of their impacts.”

The day of reckoning will occur in 2027, when the Commission will undertake its assessment of compliance with both the LULUCF and ESR Regulations for the 2021-2025 period. The ESR Regulation links compliance with the LULUCF ‘no debit’ target with compliance with the annual emission allocations under the ESR for this period. Member States in deficit on their LULUCF account will find their ESR allowances sharply curtailed, increasing the likelihood that they will enter the second 2026-2030 period with a heavy penalty on their GHG accounts in the ESR sector.

What happens if the LULUCF budget in the 2026-2030 period is not met is not determined in current legislation. It is possible this will be part of the discussions of a further revision of the LULUCF Regulation needed to allocate national targets in the context of meeting the 2040 climate target when that is agreed. Alternatively, the general infringement procedure could be used by the Commission to require Member States not in compliance to increase their ambition.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit: Photo of a beech forest was taken by Peter Prokosch and appears in the World Forest Ecosystems series, used under Creative Commons Licence CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Update 29 November 2025. The post has been revised to reflect that the ESR Regulation provides a mechanism for addressing the situation where Member States are in breach of their ‘no debit’ LULUCF obligation in the 2021-2025 period.

Humans respond to to proposals which they understand, and climate change is one issue where the communication has been poor. What makes trees and hedges so important fir carbon sequestration? What’s the big deal? It’s only when you stand in a wood, in a field, in the shelter of a hedge on a breezy day that you appreciate the way leaves clean the air passing through them. The mature woodland with trees of 70+ ft is doing so much more than a green crop that’s a ft high at best. The process can be put through a complexity machine which leaves the managers and owners of the woodland perplexed. If we want woodland for ecological reasons, they need explaining so the message is understood.