The European Commission finally put forward the EU-Mercosur Partnership Agreement concluded in December 2024 for ratification on 3 September 2025. The Commission adopted proposals for Council decisions on the signature and conclusion of two parallel legal instruments: the EU-Mercosur Partnership Agreement (EMPA) and the interim Trade Agreement (iTA). The iTA will be repealed and replaced by the EMPA once the latter is fully ratified and enters into force.

Livestock farmers continue to protest and to mobilise against ratification of the Agreement, arguing that it will open the EU market to a flood of South American imports and decimate the EU beef sector. But for beef and poultry, the tariff concessions are limited to relatively small increases in tariff rate quotas. These additional imports will result in lower prices for EU farmers compared to what otherwise they might expect, but recent empirical research suggests that the effect will be very muted.

In a recently-published paper with Alex Gohin, we estimate that if the EU had fully liberalised its beef tariffs with Mercosur countries in 2017 (the latest year for which all the relevant data for the analysis was available), beef farmers would have suffered a significant negative impact on their income of more than -5%. Because the tariff concessions are limited to two tariff rate quotas (for fresh and frozen beef, respectively), we estimate that the negative impact effect would be reduced to -0.3%. This takes into account the fact that the (small) increase in overall EU household income due to implementation of the Agreement will have a (small) positive effect on beef consumption, which will offset the direct impact of additional imports on beef prices. Indeed, if we think that the Agreement might lead to additional employment in the EU, the overall impact on beef farmers’ prices and incomes would be close to zero.

This analysis is supported by further analytical work undertaken by DG TRADE and published at the same time as the announcement of the commencement of the ratification process. This paper uses a different modelling approach, using a dynamic framework incorporating international capital mobility and capital accumulation. It projects a baseline based on population and GDP projections up to 2040 and examines the potential impact of the Agreement in that year, whereas we use a comparative static model focused on 2017. The DG TRADE paper does not adjust the impact of the proposed TRQs for MFN imports (see below) and thus exaggerates the potential impact of the Agreement on the beef market. Still, its estimate that the Agreement might lead to an increase in beef imports equivalent to 0.3% of EU beef consumption in 2040 confirms that the impact is likely to be minimal.

Despite these empirical estimates, the Commission has responded to the fears of farmers by proposing an additional legal act to operationalise the bilateral safeguard elements of the Agreement in Union law. The Commission has made a series of political commitments on how it will make use of the rights that the Union has reserved in the EMPA bilateral safeguards chapter. These include a commitment to launch investigations when imports under preferential terms increase by at least 10% year-on-year or import prices decrease by more than 10% year-on-year, provided these TRQ imports are sold at prices at least 10% lower than domestic prices.

In assessing the impact of the EU beef offer, it is important to understand how much additional beef will enter the EU market from South America when the Agreement is fully implemented. The amount is limited by the size of the additional tariff quotas but even these quotas over-estimate the likely impact. As I outlined in a previous post on the beef offer in the Mercosur Agreement, “… opening (or increasing) a TRQ does not automatically lead to an equivalent increase in imports. It depends totally on the prevailing market situation…”.

Specifically, the impact of the EU’s TRQ offers for fresh and frozen beef depends on the TRQ offered relative to the existing level of MFN imports in these sectors (for the explanation of this, see the previous post and the references given there). Given that Mercosur exporters successfully export significant quantities of fresh beef to the EU while paying the full MFN duty, our estimate based on 2024 data was that the EU’s tariff quota offer might lead to an additional 50,000t of imports rather than the full size of the two tariff quotas of 99,000t.

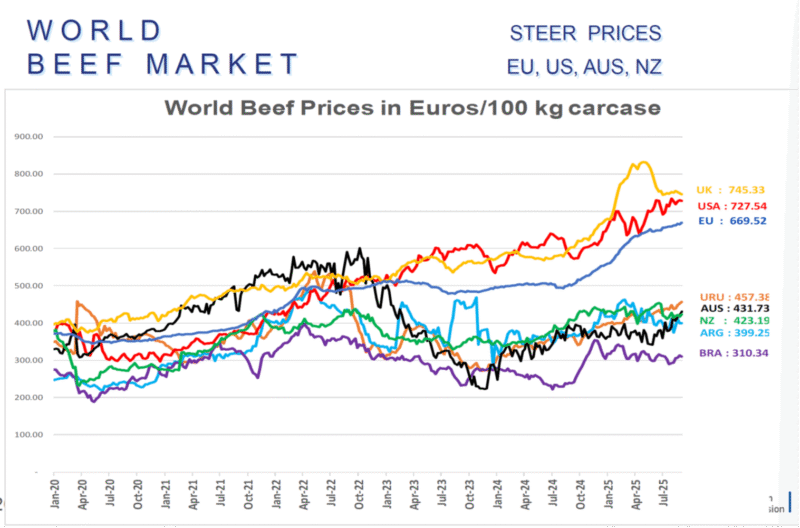

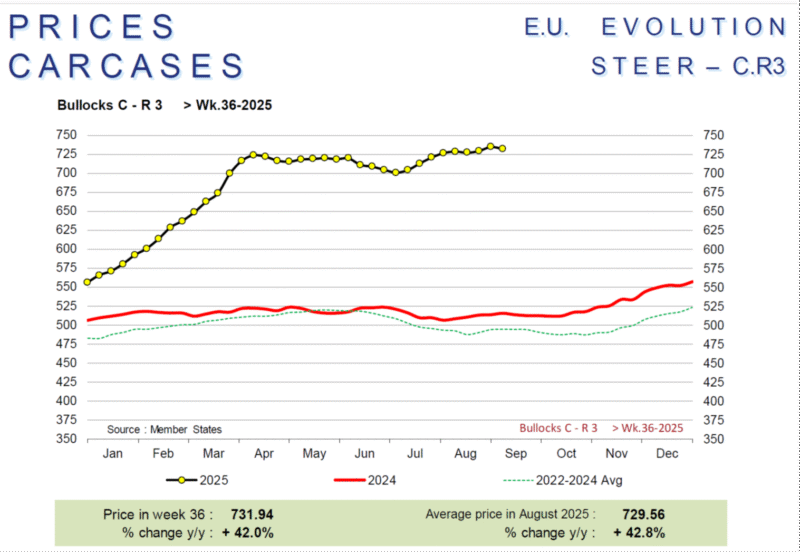

The beef market in 2025 has been flying. In August 2025, the FAO global price index for beef reached its highest level ever. Supply shortages in major exporting countries due to drought and high feed costs have combined with continued strong import demand from countries like China to push global beef prices to extraordinary levels (Figure 1). EU beef prices have followed (Figure 2), in part pulled up by the increase in global prices, but also due to a decline in EU output (estimated at -1.3% in the DG AGRI Summer Short-term Outlook 2025). The Outlook, perhaps surprisingly given the increase in retail prices for beef, expects EU beef demand to remain robust. The Outlook therefore projects a decrease in EU beef exports and an increase in imports in 2025.

Source: DG AGRI, Meat Market Observatory, 18 Sept 2025

Source: DG AGRI, Meat Market Observatory, 18 Sept 2025

In this post, I present data tracking beef imports from Mercosur countries to date in 2025 which show a further increase from these countries. Paradoxically, if the projected level of 2025 imports were to continue into the future, this would mean that EU beef farmers would have even less reason to be concerned with the impact of the EU-Mercosur Agreement beef quotas as their impact on EU market prices would be even smaller than hitherto estimated. This is because the increased imports, which are (mostly) paying the full MFN tariff, will substitute into the Mercosur tariff quotas as they are implemented, meaning that the incremental exports from Mercosur will be even less than feared.

The overall evolution of beef imports

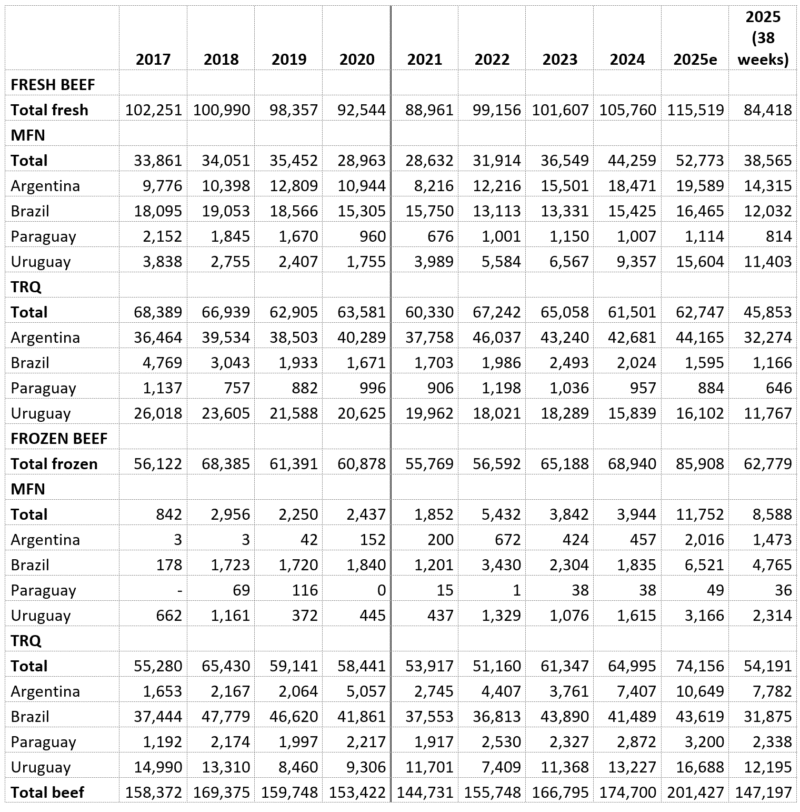

Table 1 shows imports for fresh and frozen beef from all sources into the EU over the period 2017 to the latest week in 2025 at the time of writing. These data are based on DG TAXUD weekly import statistics of agricultural products based on the “Surveillance” System of the Taxation and Customs Union DG. This is a different data source to the Eurostat COMEXT trade statistics (see my previous post for a discussion). One advantage is that they are almost instantaneous. They also provide a breakdown of imports by trade regime – either Most Favoured Nation (MFN) imports that pay the full tariff, Tariff Rate Quota (TRQ) imports where a limited quantity of imports benefit from preferential access, and other Preferential imports where imports benefit from preferential tariffs under free trade agreements.

DG TAXUD data are based on customs statistics. The UK is no longer a Member State of the European Union, however until the end of the transition period on December 2020 it was still part of the EU Customs Union. The DG TAXUD trade data therefore also include the UK as long as it was part of the Customs Union. This impact of Brexit needs to be kept in mind in comparing import statistics up to 2020 and those after 2020.

I described the various Tariff Rate Quotas and the beneficiary countries in the previous post. Preferential imports since 2021 come largely from the UK under the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement. There are also traditional imports from Southern African countries (Namibia, Botswana, South Africa) and some imports from Chile under the EU FTA with that country.

Table 1 shows imports of fresh and chilled beef, and frozen beef, as these are the products for which Mercosur tariff quotas will be opened. The other major category of beef imports is beef preparations (such as corned beef) as well as minor imports of live animals, beef offals, beef fats and salted and dried beef. The figures for 2025 cover the period up to Week 39 (end of September). I have projected total 2025 imports on the assumption that the average weekly rate in the first nine months will continue for the remaining three months of the year, thus ignoring any possible seasonal effects.

Source: DG TAXUD, Weekly imports, on the DG AGRI Agri-food data portal.

There are four main messages from Table 1:

- There has been a steady increase in beef imports between 2021, the first post-Brexit year, and 2024 and this continues into 2025 though at a slower rate. This confirms the projection in the DG AGRI Summer short-term outlook for 2025 that, despite the fall in EU production and the very high prices, EU consumption has remained rather robust and imports have somewhat increased to fill the gap.

- This increase is entirely due to increased imports of frozen beef. Total imports of fresh beef dropped in 2020 due to Covid when restaurants were closed, but recovered again in 2021 even though the UK is no longer included in the figures. For the three years 2022-2024 total fresh beef imports have stabilised at just over 180,000t cwe. 2025 imports of fresh and chilled beef are projected to be slightly lower than in 2024, which would reflect some consumer response to higher beef prices.

- Although frozen beef imports also fell in 2020 due to Covid, there has been a steady increase since then, with 2025 projected to show the largest annual increase. Looking at the classification by trade regime, these increases reflect increases in both MFN and TRQ imports. The increase in MFN imports reflects the high world market prices and the fact that most EU protection consists of a specific tariff. At the world prices prevailing in the early 2020s, EU protection amounted to a prohibitive ad valorem tariff equivalent of 60% (see previous post). The result was almost no MFN imports of frozen beef (see Table 1). With higher world market prices, these tariffs are less prohibitive and MFN imports have increased. For TRQ imports, there has been no increase in TRQ ceilings in 2025 so the explanation for higher TRQ imports must be that the tariff quotas have been better utilised.

- For fresh and chilled beef imports, the breakdown by trade regime is especially interesting. While projected total 2025 imports are projected to fall slightly, this reflects entirely a fall in preferential imports, which in turn is due to a fall in imports from the UK where the beef herd has been declining. Fresh beef imports under TRQs, which unlike frozen beef TRQs are generally well used, do not show any change. However, projected MFN fresh beef imports in 2025 show a further increase compared to 2024. Again, it is likely that the lower effective protection due to higher world market prices has contributed to this increase.

Beef imports from Mercosur countries

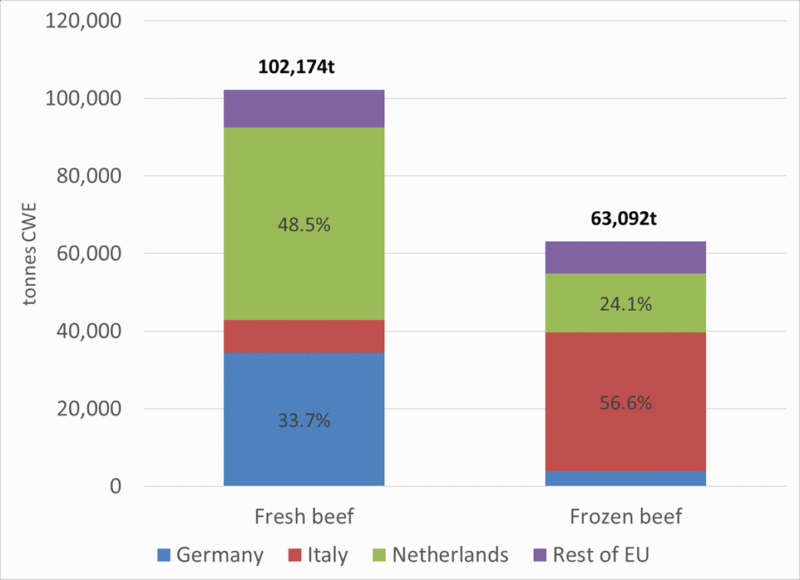

Before looking at the trends in beef imports from Mercosur countries, the destination of these imports tells an important story (Figure 3). For fresh and chilled beef, almost half is imported into the Netherlands and a further one-third into Germany. Imports into the Netherlands may be an example of the ‘Antwerp-Rotterdam’ effect where imports are consigned to importers based in the Netherlands but are subsequently distributed to other EU countries.

The destinations for frozen beef are quite different. Here, Italy alone accounts for nearly 60% of such imports, with the Netherlands accounting for a further one-quarter. Italy’s famed bresaola della Valtellina (PGI) is made from air-dried, salted beef. It requires lean, high-quality cuts, which is mostly sourced from zebu cattle raised in South America. Italian and EU beef production cannot meet the volume or price point needed for industrial bresaola production. Some sources suggest that 90% of the beef used for this production comes from South American zebu cattle, mostly from Brazil and Uruguay. The bresaola della Valtellina PGI designation requires strict adherence to quality standards, but it does not mandate a specific origin for the meat itself, allowing for the use of meat from South American zebu. Imported beef is also used in salami, carpaccio, and other cured or cooked beef products. Brazilian meat firms such as JBS have invested heavily in Italy for the manufacture of these products in order to have a smooth supply chain and consistent quality.

Source: DG TAXUD, Weekly imports, on the DG AGRI Agri-food data portal.

Against this background, we now present the figures for beef imports from Mercosur countries in Table 2, using the same distinction between MFN and TRQ imports (there are no preferential imports from these countries as no FTA is in place). Overall, there is projected to be a significant further increase in beef imports from Mercosur in 2025 even compared to 2024, from around 175,000t to just over 200,000t. What is interesting is the breakdown of these projected imports.

Source: DG TAXUD, Weekly imports, on the DG AGRI Agri-food data portal.

Looking first at fresh beef, projected 2025 imports show a significant increase. As there is only a minor increase in their exports under the fresh beef TRQs, virtually all of this increase represents an increase in MFN imports which are projected to increase from just over 44,000t in 2024 to almost 53,000t in 2025. While imports from Argentina and Brazil are projected to increase by around 1,000t each, the big increase is in fresh beef imports from Uruguay, which are projected to increase by more than 7,000t.

Turning to frozen beef, an even greater increase in imports is projected, from 68,000t to 89,000t. This time, most of this increase will come from an increase in imports under existing TRQs, reflecting higher utilisation rates. But a significant increase in MFN imports is also projected, reflecting the easier access to the EU market when world beef prices are high.

When assessing the likely impact of the EU offer to Mercosur in the Partnership Agreement, it is the MFN imports we need to keep an eye on. The theory of tariff quotas demonstrates that opening a TRQ only increases imports to the extent that the TRQ is greater than the level of imports that enter under MFN tariffs. In our empirical analysis quoted earlier, we assumed a level of MFN imports when the TRQs were phased in of around 45,000t. We also noted that some Argentinian exports currently entering under the Hilton beef quota would be reallocated to the Mercosur quota as that quota was redirected to US imports. This was the basis for our assumption that the opening of the two TRQs would lead to additional imports of around 50,000t.

Projected 2025 MFN imports of fresh and chilled beef already exceed the fresh beef TRQ of 54,500t offered to Mercosur countries. If the Mercosur countries were to maintain this level of fresh beef exports up to the time when the TRQ is fully phased in five years after ratification, it means there will be no additional beef imports from Mercosur under this TRQ.

The frozen beef TRQ offered to Mercosur is 44,500t. Projected MFN frozen beef imports from Mercosur exporters in 2025, despite the increase, will still be quite limited, at around 11,500t. Assuming no further increase between now and five years after ratification when the TRQ is fully open, we might expect this TRQ to lead to an increase of around 33,000t of beef. Taking the fresh and frozen beef quotas together, the likely additional imports of 33,000t from Mercosur countries is only one-third of the size of the quotas that are opened.

Conclusions

Fears have been fanned, not least in France, that the EU-Mercosur Agreement will open the floodgates to South American beef imports and lead to a collapse in the EU beef market. On September 26, 2025, farmers from Île-de-France gathered in front of the Château de Versailles with tractors and banners reading “The peasant revolt resumes in Versailles,” echoing the revolutionary spirit of 1789. On October 14, the Confédération Paysanne is organising a large-scale demonstration with tractors in the capital, coinciding with the trial of two union members arrested during a previous protest, adding symbolic weight to the event.

The purpose of this blog post is to highlight that these fears are greatly over-estimated and exaggerated. The EU offer is not for full liberalisation of beef imports, but is limited to specific tariff quotas for fresh beef and frozen beef together amounting to 99,000t compared to EU consumption of 6 million tonnes. When compared with existing imports of beef from Mercosur countries which pay the full MFN duty, and which would switch into the TRQ category when the Agreement is ratified, the expected increase in imports could be as little as one-third of this amount, or 33,000t. Further, all of this increase will be in the form of frozen beef imports which does not compete with European beef in supermarkets and restaurants, but is mainly destined for manufacture into meat products like bresaola or sausages in Italy and other countries.

The analysis in this blog post has some caveats. It is based on trade figures up to the end of September, so the figures for 2025 are projections and actual imports could turn out to be different. High world beef prices have lowered the effective protection for EU beef producers and encouraged additional MFN imports. These high prices will not last, but on the other hand prices are unlikely to fall back to the ‘normal’ levels of recent years as grazing lands around the globe become increasingly exposed to droughts and other climate extremes. European farmers may well experience increased competition from Mercosur exporters. But this will be due to changes in relative competitiveness arising from issues such as changes in real exchange rates (what value will the Argentinian peso have in seven years’ time?) and the removal of export taxes on beef exports in Argentina.

In this context, the likely impacts of the Mercosur Agreement for beef farmers will be hardly noticeable, but the gains for the European Union from ratification in an increasingly turbulent goe-political world will be significant. The EU-Mercosur Partnership Agreement should and must be ratified.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit: Own photo, Copenhagen.