A rather specific feature of the EU’s agricultural policy has been its use of export subsidies to maintain market prices on its domestic market in the past. While the EU was not the only country to make use of this policy mechanism, it accounted for around 90% of global expenditure on formal export subsidies (while arguing that other countries provide export support through more indirect means, such as through state monopoly marketing boards or through food aid).

EU use of export subsidies has fallen dramatically although they still have not disappeared. Total expenditure on export refunds fell from €3.8 billion in 2003 to a projected €139 million set aside in the EU’s draft 2012 budget (at their peak in the late 1980s and early 1990s, they amounted to €10 billion per year). Pigmeat, poultrymeat, eggs, beef and some non-Annex 1 (that is, processed) food products are now the only beneficiaries.

It is surely time for the EU to renounce the use of this policy instrument in the new CAP after 2013. Ideally, the provision for export subsidies should be eliminated from the single common market organisation regulation. A less satisfactory outcome would be a self-denying ordinance by the Council and the Parliament not to make use of the instrument after 2013.

The Commission argues that export subsidies are part of the WTO multilateral negotiations and are not under discussion in the current CAP review. It has offered to abolish export subsidies as part of an overall Doha Round agreement which would also eliminate other similar forms of export support.

It takes the view that it would be wrong to weaken its bargaining position in those negotiations by unilaterally disarming and foregoing the use of export subsidies before a final agreement is reached. This argument does not hold water: export subsidies are a very expensive and costly way to provide support to farmers regardless of the outcome of the Doha Round.

The cost of export subsidies…to the EU itself

Export subsidies are not only damaging to producers in other countries and to the EU’s trade partners, but a study by the Scottish Agricultural College (SAC) last year shows just how costly they are for the EU itself. This study used the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) model to examine two alternative situations (the model is modified to better take account of some specific features of agricultural markets including adding a flexible land supply).

Simulation 1 (S1) looked at the implications of abolishing export subsidies. Simulation 2 (S2) examined what might happen if the EU made full use of its export subsidy entitlements under the current WTO Agreement on Agriculture (called the ‘maximum damage’ scenario in the report). In both cases, the results were compared to a baseline scenario (S0) assuming a continuation of the status quo. (In fact, the study examines a broader range of scenarios but to keep the summary simple I focus here on some key results).

Because of the time and resources required to put together the database for a global model such as GTAP, it is inevitable that the data in such a model is always behind the curve. In the case of the GTAP model, the SAC study uses Version 7 of the database which is based on the 2004 year. In the baseline scenario (S0), the model database is projected forward from 2004 to 2013.

In the version used in the study, the 2013 year differs from the 2004 year mainly by taking account of known EU policy changes (enlargement, decoupling, lower intervention prices, new preferential trade agreements); economic growth over the period either in the EU or its trading partners is not taken into account. Apart from these known policy changes, in the baseline, tariff rates and, importantly, export refund rates, are assumed to be the same in 2013 as they were in 2004. Thus, the simulations S1 and S2 are compared to a situation where the EU is assumed to apply the 2004 export subsidy rates in the policy environment projected to prevail in 2013.

Export subsidy expenditures can vary, but are required to remain within the EU’s WTO Agreement on Agriculture ceilings. For example, because of the agreed expansion in dairy quotas up to 2013 (‘soft landing’), the model projects that the EU raw milk price and dairy product prices fall in the baseline S0 scenario compared to 2004, resulting in significant purchases of dairy stocks and accompanying dairy export refund increases.

Figure 1 shows the use made by the EU of its allowed export refund ceilings in 2004 and the refund rate as calibrated in the GTAP database. Export refund rates were between 25-30% for a range of products – other grains, red meat, dairy, rice and sugar. High utilisation figures for the EU’s WTO ceilings are shown for other food products, dairy, sugar and, to a smaller extent, rice and white meat. Very low use was made of export refund entitlements in the wheat, other grains and oilseed sectors.

In the S1 (‘elimination’) scenario, these export subsidies are eliminated entirely. In the S2 (‘maximum damage’) scenario, refund rates are increased to ensure that the WTO ceilings are fully exploited. This has a big effect on support for wheat and other grains, particularly.

Scenario S1 (‘elimination’) considers the effect of eliminating all export subsidies in the GTAP database (but the EU accounts for 90% of the total), as well as suppressing intervention prices and stock purchases. Thus it measures the impact of the ‘business as usual’ scenario (S0) on world markets.

EU27 production would contract in the subsidised agrofood sector, with the largest percentage falls occurring in the dairy sector (5.1 per cent) and consequently, upstream raw milk production (3.6 per cent). In the EU27 ‘red meat’ and ‘other food’ sectors, production would also decline by 1.8 per cent and 0.5 per cent, respectively, whilst falls in cereals and sugar production are relatively modest.

World prices would rise for agro-food commodities, although aside from dairy (where EU export refunds are considerably more pervasive), these increases are relatively moderate since in some commodities, export trade volumes are small (i.e., rice), or because the export refund rate is low (i.e., cereals).

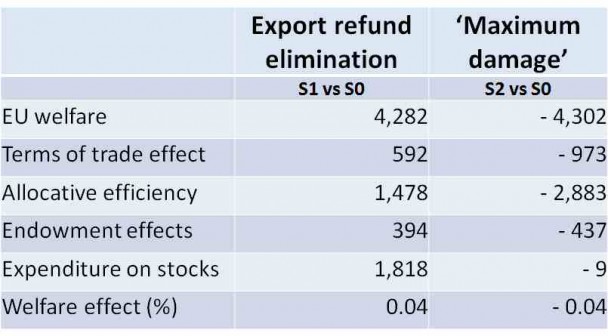

However, it is the impact on the EU itself to which I want to draw attention (Figure 2). Overall, the study estimates a gain in EU welfare of €4.2 billion from elimination of the 2004 level of export refunds. This includes savings compared to the baseline in dairy intervention stock expenditure of around €1.8 billion. Arguably, these dairy intervention stocks in 2013 do not have a zero value so the expected EU welfare gain from eliminating export refunds as they were in 2004 is over-stated somewhat in the study.

Even more significant are the additional welfare losses in the S2 ‘maximum damage’ scenario compared to the baseline. This shows the additional costs to the EU of actually making use of its allowed export refund ceilings under the WTO agriculture agreement. We might envisage this scenario in a situation where world market prices collapsed. The overall cost would be a fall in welfare of a further €4.3 billion, or a total loss of welfare compared to the elimination of export refunds of €6.7 billion (ignoring the cost of stocks).

These figures clearly bring out the high cost of this policy to the EU itself. In the ‘maximum damage’ scenario, export refund expenditure would rise to the allowed WTO ceiling of €7.4 billion. Making full use of this option would cost the EU in lost welfare at least €6.7 billion (depending on how dairy stocks are valued in the baseline scenario in 2013). While the study does not report the change in EU real income between farmers, consumers and taxpayers in the two simulations, and so it is not possible to compare the cost of the export subsidy expenditure to the gain in farm income, it is obvious that overall this is a really expensive way of trying to support farm income.

Political responses

Not all agricultural commodities are eligible for export subsidies. The proposed single CMO regulation would cover cereals, rice, sugar, beef and veal, milk and milk products, pigmeat, eggs and poultrymeat. Products such as wine and fruits and vegetables which were eligible for export refunds in the past are no longer eligible following the reforms of these market regimes.

There is now a growing consensus within the EU in favour of eliminating the remaining use of export subsidies. The European Parliament in its resolution on Investing in the future: a new Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for a competitive, sustainable and inclusive Europe is in favour. The Parliament

Supports food autonomy of developing countries; recalls the commitment made by the WTO members during the 2005 Hong Kong Ministerial Conference to achieving the elimination of all forms of export subsidies; considers that the new CAP must be in line with the EU concept of policy coherence for development; underlines that the Union must no longer use export subsidies for agricultural products and must continue to coordinate efforts with the world’s major agriculture producers to cut trade distortion subsidies;

Quite a number of Agriculture Ministers in the discussion of the CAP reform proposals at the Agricultural Council meeting in January earlier this year unprompted also called for their elimination.

Even COPA-COGECA, while calling for the retention of the export subsidy mechanism until the parallel elimination of export subsidies and all other similar forms of public support to exports by all members of WTO, has accepted that the EU should not use export subsidies on exports to LDCs or ACP countries.

Now is the time to act!

This post was written by Alan Matthews.