Last week Dacian Ciolos welcomed the launch of the UN’s International Year of Family Farming 2014 and on Friday this week the Commission is holding a conference in Brussels on “Family farming: A dialogue towards more sustainable and resilient farming in Europe and in the world”.

The Commissioner emphasised that over 95% of farm holdings in the EU are family farms, and that “family farms are the foundations on which Europe’s Common agricultural policy was built. They continue to stay at the heart of European agriculture as robust generators of competitiveness, growth and jobs, of dynamic and sustainable rural economies.”

Others take a different view of structural developments in EU farming. The view taken by the Future Farmers in the Spotlight website run by a group of young Dutch agriculturalists would be shared by many NGOs:

The agricultural sector went in the last decades through an enormous structural transformation. Away from the small scale family farms towards large, capital intensive, fully mechanised and specialised industrialised farms. Corporate agricultural business thrive while small and middle sized agricultural companies vanish.

In this post, I try to understand the reasons for these different perceptions of the position of family farms and I discuss the role of policy in supporting family farms. The debates, in part, pivot around the distinction between family farms and small farms. As we will see, all small farms are family farms, but not all family farms are small farms.

Family farms and small farms in the EU

There are around 12 million farms/holdings in the European Union with an average size of 14.2 hectares. The vast majority of these farms are family farms which are operated as family-run businesses in which the farm is passed down from generation to generation (see diagram). One indication of the importance of family farming is that about three quarters (77.8 %) of the labour input in agriculture came from the holder or members of his/her family in 2010. For some countries, such as Ireland and Poland, the proportion is over 90%. There are only a few member states (France, Czech Republic, Slovakia) where non-family labour accounted for a majority of the labour force in 2010.

Large incorporated farms operated mainly using wage labour exist, especially in confined livestock enterprises and in the successors to the former state and collective farms in the countries of central and eastern Europe that previously had centrally-planned economies. Although few in numbers, they utilise around one-quarter of the agricultural area and account for somewhat less of agricultural output, although these shares are higher in specific countries.

Nonetheless, confusion arises because in political debate the term ‘family farms’ is used as a euphemism for small farms rather than as a description of the legal status of a farm. Family farms operate at very different scales within the EU. This perspective is underlined by the most recent structural data from Eurostat from the 2010 Agricultural Census.

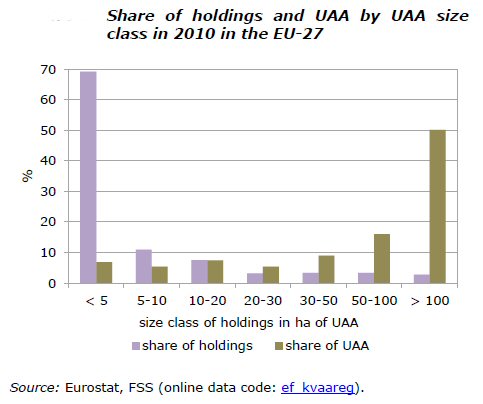

On the one hand, there were a large number (5.7 million or almost half of all holdings) of very small farms (less than 2 hectares in size) that farmed a small proportion (2.5%) of the total land area used for farming in 2010 and, on the other, a small number (2.7% of all holdings) of very large farms (over 100 hectares) that farmed one-half (50.2%) of the farmland in the EU-28.

The contrast is even more marked if the comparison is made in terms of the economic size of holdings. 5.5 million farms (44.6%) had a standard output below €2,000 in 2010 and were responsible for only 1.4% of total agricultural economic output. By contrast, the 1.9% of holdings that had a standard output in excess of €250,000 accounted for almost one half (47.8%) of all agricultural economic output.

There is strong political support for the maintenance of family farming in Europe, where family farming is interpreted to mean the sub-set of small family-owned farms contrasted with larger, more industrial units, whether family-owned or not. In practice, it is difficult to know where to draw the line, an issue discussed in this Agricultural Economic Brief from DG Agriculture and Rural Development. One plausible definition of what political campaigners mean by family farms is those farms where the family provides the bulk of the labour.

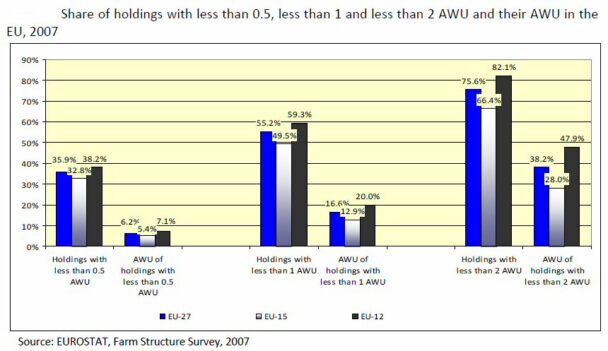

The figure below looks at the shares in the numbers of holdings and in the total agricultural workforce of holdings with less than 0.5 Agricultural Work Unit (AWU), less than 1 AWU and less than 2 AWU, respectively (this time, using 2007 data because the graph is more easily available). Taking the most expansive definition of family farms as those with up to 2 AWUs (which could be farmer and spouse, or father and son, or farmer and one hired worker), we see they account for about 75% of the total number of holdings in the EU-27, but less than 40% of the total agricultural workforce measured in AWU. My claim is that it is this group of farms that campaigners describe as family farms when campaigning to save the family farm.

SWOT analysis of (small) family farms

Family farms in this sense are seen as being better custodians of the countryside, ensuring more varied landscapes, more sustainable use of natural resources and better provision of public goods than larger farms. Larger farms are seen as more prone to specialisation and monocultures, to the removal of hedgerows and to unsustainable intensification. Smaller farms are also seen as playing an important role in supporting rural employment and maintaining the social fabric of rural areas and thus contributing to the objective of balanced territorial development (see this statement prepared by the Lithuanian Presidency for the informal Agricultural Council in September this year). While some of these claims are undoubtedly valid, others take the form of family farm ‘myths’ that are not necessarily supported by empirical evidence (see this OECD publication for more details).

However, the number of farms is steadily declining as labour moves out of the agricultural sector making land available for consolidation. This land tends to be acquired by larger farms which benefit from economies of scale and where the farmer often has a higher level of education and skills. Thus, over time, the concentration of land use and more particularly production has been increasing. As noted earlier, some voices within the EU would like to halt or slow down this process, even while others seek to encourage it as the basis for creating more viable and competitive holdings.

A second challenge in a predominantly family farming structure is access to land. Where land is mainly passed on within the family, younger farmers must wait until the older generation are willing to relinquish management control and pass on the farm before they can become farmers in their own right. With older farmers living longer, and with significant inducements for them to remain in farming and few incentives to leave, Europe’s farm workforce is gradually ageing creating substantial barriers for new entrants. With the growing capital needs of agriculture, another issue for young farmers is access to capital which must all be supplied through credit. These two problems are exacerbated by the relatively very high land prices in Europe, in part due to the density of population and the demand from alternative land uses.

A third particular structural challenge for the European Union concerns the future of the very large number of very small farms, the half of all farms smaller than 2 hectares; 2.7 million of these farms are in Romania alone. Many of these farms may be characterised as semi-subsistence farms, meaning that more than 50% of their output is self-consumed; Eurostat has estimated that there were around 6 million such semi-subsistence farms in 2007. Their problems are low cash incomes and a high incidence of poverty. Frequently, these semi-subsistence farms are run by older farmers with low levels of general and agricultural education who are not generally innovative. From a production point of view, they represent a sub-optimal use of land and labour and make a poor contribution to rural growth. However, they can be important from a welfare point of view in reducing the risk of rural poverty by providing a basic minimum of household food security in countries which otherwise have relatively low levels of social safety net (Sophia Davidova has a good discussion of semi-subsistence farming in Europe on which I have drawn for this paragraph; see also this recent European Parliament report).

Policy interventions to support family farming

Many of the interventions to support family farms have been adopted by the member states, although policy instruments at European level under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy are also important.

The measures adopted by member states to influence structural change/support family farming include land consolidation schemes to reduce farm fragmentation by land re-parcelling and amalgamation; land market regulations to regulate land sale and price; special agricultural taxation arrangements that favour family-owned businesses such as partial or total exemption from property or inheritance taxes or social security taxes; and measures to facilitate access to farm credit or insurance.

For much of its history, farm support under the CAP was provided through market price support which does not discriminate between farms on the basis of size but arguably benefits larger farmers more. The substitution of direct payments for market price support allows the targeting of support to smaller farmers. However, there has been very limited targeting of support payments in the EU.

In the recent political agreement which set the shape of the CAP for the next seven years 2014-2020, a new option to target support on smaller farms (a ‘redistributive’ payment) has been introduced but it is optional for member states to use. Also, the possibility to reduce payments above a (rather high) threshold has been introduced but again, apart from a small mandatory reduction, any further degressivity is at the discretion of individual member states.

Additional funding is targeted in Pillar 1 to younger farmers (defined as those under 40 years old) in an attempt to loosen up the inter-generational transfer of holdings. As the problem lies more in the unwillingness of the older generation to exit farming and hand over their farm to their heir, the efficiency of this new measure in encouraging earlier transfers is doubtful, and there is likely to be a high degree of deadweight loss.

A ‘transitional’ measure to support semi-subsistence agricultural holdings undergoing restructuring was introduced in the rural development regulation following the accession of the central and eastern European member states in 2004. Essentially, these farmers could be granted a flat-rate aid for a maximum period of five years provided they submitted a business plan. The purpose of the scheme was to encourage semi-subsistence farms to increase their engagement in commercial agriculture.

Uptake of the scheme was below expectations in those member states that introduced it. In part, this may reflect the nature of the scheme which might not have been well suited to the target population and to the restrictive rules surrounding eligibility. A more general critique is that the measure focused solely on support to agricultural production when the ultimate objective should have been to assist the household to improve its income no matter whether it comes from agricultural or non-agricultural activities.

This measure has not been renewed in the latest CAP reform; instead, a simplified scheme of lump-sum payments to small farmers funded under Pillar 1 has been introduced, although again this is optional for member states to implement.

A controversial issue will be the setting of the minimum farm size for payment. In the current programming period, for example, Bulgaria set a minimum farm size of 1 ha, thereby eliminating over 1 million very small farms from support (although the amount of funding each holding less than 1 ha would have received would have been miniscule and probably less than the administrative cost of providing this support).

In fact, the new rural development regulation in this political agreement does not explicitly mention family farms although family farms will benefit from many of its measures, including investment grant aid, aid to farmers in areas of natural constraints, funding of agri-environment measures and aid to form producer groups and to take part in other forms of co-operation, including the development of short supply chains and local food systems. It is possible that the design of these measures in member states’ rural development plans, including eligibility conditions, could favour smaller farms (for example, through upper limits on the amount of agri-environment aid per farm). But it is equally possible that member states may want to concentrate support on ‘viable’ holdings or holdings above a specified size threshold, both of which would exclude many smaller farms from participating.

What seems clear from this account is that the concept of ‘family farming’ has different meanings for different speakers, which in itself should make for an interesting debate at the conference next Friday. In political discourse, many view family farms as synonymous with smaller farms which make up about three-quarters of all holdings but account for only two-fifths of overall labour input. Whether there is a political desire to privilege support for this particular group of farms is far from clear; one answer will be provided by the use made by member states of the optional measures to cap farm support per farm and to introduce the redistributive aid in Pillar 1, and by the design of rural development measures in Pillar 2.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Picture credit: Irish Independent

Dear Alan,

Thank you for raising this important topic. You mentioned some very important points. Possibly, you have left out two other points.

First, many of the small farms are part-time farmers. Here are some facts on income from Germany. These part-time farmers earn only 17 percent of total income from agricultural activities. Moreover, there total income is higher than the income per labor unit of full-time farms. Total net income of part- time farmers is also higher than the average household income in Germany. There is hardly any justification for supporting part-time farrmers in all EU countries due to low income. If support is needed due to low income in some countries it is a social problem and the states are responsible and not the EU.

Second, I thinkt it is also important to mention the governance problem. It might be costly to control whether some old part-time farmers are still cultivating their land or whether they have leased it out. You may need even more inspectors in countries like Romania and Bulgaria. The system may have an additional effect on corruption.

Kind regards,

Ulrich

@Ulrich

You are absolutely right to emphasise the importance of off-farm income and pluri-activity in maintaining the viability of many small farms. To your German experience I can add the Irish figures. In 2008 (i.e. just before the Great Recession hit Ireland), around 40% of all Irish farm households had an off-farm job and off-farm income (often this is the spouse rather than farmer) and this income accounted for 80% of their total household income. So this is an aspect which should be more emphasised in explaining the future viability of (small) family farms. .Unfortunately, as a result of the Great Recession many of these jobs in rural areas have disappeared, particularly those related to construction, so it is important to look at the trend in multiple income sources when evaluating changes in farm living standards over time.