Last week the Irish government launched the latest in a series of rolling ten-year strategies for the Irish agri-food sector called Food Wise 2025 (FW2025). The report follows in the footsteps of Agri Food 2010 (published in 2000), Agri Vision 2015, Food Harvest 2020 (full disclosure: I was a member of the committees that drafted those two reports) and now Food Wise 2025. In this post, I review the latest strategy and comment, in particular, on its environmental implications.

While Food Harvest 2020 (FH2020) contained a number of detailed sectoral targets, Food Wise 2025 avoids this level of quantification and contains just four headline aspirations:

• increase the value of agri food exports by 85% to €19 billion,

• increase value added to the sector by 70% to €13 billion,

• increase the value of primary production by 65% to €10 billion.

• In turn, achieving these targets is expected to deliver a further 23,000 jobs in the agri food sector by 2025.

The draft Environmental Report of the Strategic Environmental Assessment accompanying the publication of the strategy explains that “given that the focus of the Strategy has been to increase value rather than production, the Agri-Food Strategy 2025 committee sub-groups did not attempt to translate the ambitions for each sector into specific headline quantitative production targets numbers when framing the Strategy.”

When asked about the absence of specific sectoral targets for primary agriculture in FW2025 compared to FH2020, John Moloney, the former Group Managing Director for Glanbia plc who chaired the group, stated that “Food Wise 2025 is more scientific in its approach which allows for just one singular target”.

More likely is that trying to agree on targets is always a fraught process in a committee which is selected to be representative of the major sectors and stakeholders. While high targets can be seen as hostages to fortune, some want high targets because they give a lever to press for advantageous policy changes if performance is not on track, and no sector wants to accept a target which foresees a contraction in their output.

Specific targets can also act to crystallise opposition from those who are less enthusiastic about high growth targets, in the way that the 50% target for increased milk output in FH2020 drew the ire of environmental NGOs worried about the environmental impact of increased dairy cow numbers. So, on this occasion, there are fewer targets and, importantly, these are formulated only in value terms.

Growth and sustainability

Whatever the reasons, FW 2025 talks about ‘growth opportunities’ rather than growth targets. The heart of the report is over 350 specific recommendations which are put forward to enable the agri-food sector to take advantage of these growth opportunities.

These growth opportunities are seen as arising mainly from three changes in the economic environment for the agri-food sector, namely the abolition of milk quotas from 1 April this year, strong demand for protein (livestock products and seafood) arising from growing economic prosperity in emerging markets and Africa, and more differentiated consumer demand opening up high value added opportunities in consumer markets.

At farm level, the game changer is the abolition of milk quotas. Taking just the first two months after quota abolition, milk production has grown from 1.47 billion to 1.65 billion litres between April and May 2014 and April and May 2015. This represents an increase of 12.2% in the volume of milk collected during these periods, which if sustained represents a good step to the 2020 target of a 50% increase in milk deliveries in 2020 compared to 2007-2009.

At food industry level, the opportunities are seen in meeting demand at the high end of the market. “Irish food and drink exporters will find their greatest opportunities where they provide offerings that target different life-stage requirements, fit into the lifestyle choices associated with convenience and well being, and provide products with clear nutritional and health benefits.” One role model is Glanbia which now has a 12% market share in the global sports nutrition market based on whey protein isolate which is a by-product of the manufacture of cheese.

The report is at pains to emphasise that the growth potential of the sector “must be realised in an environmentally efficient and sustainable manner”. The strategy emphasises that “‘The appropriate nurturing and strengthening of [the agri-food sector’s] sustainability credentials in parallel with increases in production levels will ensure that the comparative advantages of the sector are maximised for the Irish economy and environment into the future.”

The 2025 strategy is focussed on developing technologies and processes which support a vision of sustainable intensification. This strategy will support continued investment in environmentally sustainable approaches to agriculture, food and forestry production based on the latest scientific evidence and targeted at delivering public goods, economic growth and supporting the development of sustainable rural and coastal local communities.

The report concludes that “A guiding principle to meet these sustainability goals will be that environmental protection and economic competiveness will be considered as equal and complementary, one will not be achieved at the expense of the other.”

To assess the environmental consequences of the strategy, it was subject to a Strategic Environmental Assessment which has resulted in a draft Environmental Report. This is in some ways a curious document, but more of that later. Let us first examine the headline targets in the strategy and then the key recommendations before turning to an assessment of the environmental impacts.

The headline growth targets

As noted, there are three headline targets, or aspirations, which if achieved are expected to lead to the creation of an additional 23,000 jobs directly in the agri-food sector plus further jobs outside it.

The first point to note is that the targets are set out in value terms. In principle, therefore, they could be met either through higher prices or increased output. The second point to note is that the first two targets will be driven largely by developments in the food industry sector, while the third target relates specifically to primary agriculture, forestry and fisheries.

The scale of the anticipated growth underlying the three targets is highly ambitious, though not unprecedented. For example, during the ‘golden age’ for the agri-food sector following EU membership in the period 1973-84, agri-food sector value added increased by 330% and the volume of primary agricultural output alone increased by 50%.

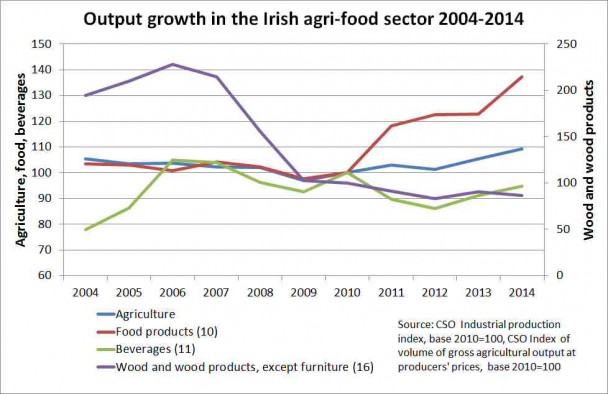

The new targets should be seen in the context of recent trends. While only one of the targets (that for the primary sector) refers specifically to output growth (and that in value terms), the recent output growth performance of the different sectors provides some relevant context. Indices of the volume of output growth in primary agriculture, food, beverages and the wood sector are shown in the chart below.

If we focus on the period since 2009 (the low point following the 2008 financial crisis), output in the food industry has increased remarkably and, to a much smaller extent, so has output in primary agriculture. The 40% increase in the volume of food industry output between 2009 and 2014 is really impressive; it was driven by increases in meat processing, bakery and other processed foods, while dairy processing output was static over this period. The contrast with the period of stable, even falling, output between 2004 and 2009 is particularly noteworthy.

However, output in the beverages sector, despite the hype about new Irish whiskies and craft beers, has steadily declined since the peak in 2006; it is too early to say if the upward trend since 2012 will be sustained. Output in the relatively small wood sector showed exceptional increases in the period 2004 through 2007 and the fall since then is a reversion to its more ‘normal’ level.

Agricultural output is up 13% in 2014 on the bad year in 2009. Over a long period between 1990 and 2010 the volume of agricultural output was totally stagnant (to base 2000=100 the index was 97 in both years), so the upward trend since then is significant. But maintaining the 2% annual growth rate implicit in this rate of expansion would still only increase agricultural output by 27% in 2025 over the base period 2012-2014.

A 50% growth over 12 years (as projected for milk output in FH2020) implies an annual growth rate of 3.5%. But milk accounts for just over a quarter of the value of gross agricultural output, Unless we assume that other sectors will grow at the same rate as milk, the overall growth rate for primary agriculture even optimistically would seem to lie closer to 2% than 3.5% per annum. This is a long way from the targeted 65% growth in the value of primary output (the latter also includes fish and forestry).

The future outlook for farm prices

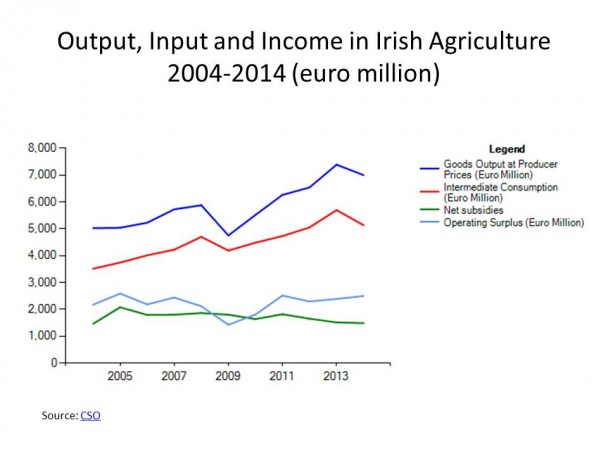

To what extent might higher prices help to fill the gap? The recent performance of primary agriculture in nominal terms is shown in the next diagram. In the years since 2010 (which is a better base year to take as 2009 was clearly an abnormal year) nominal output has increased by almost 27%, of which 9% was volume and the remaining 16% was price. Clearly, if the same relativity prevailed into the future, the FW2025 target could be easily met given the assumed rate of growth in output volume.

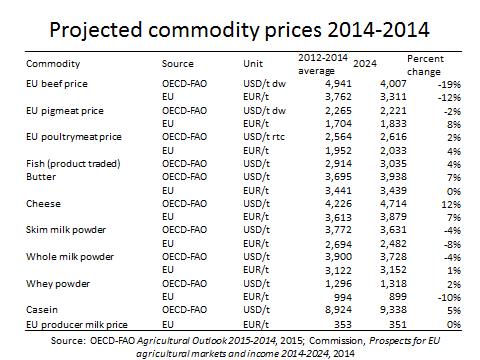

But relying on continued price increases of this scale may be imprudent. Coincidentally, just a few days before the launch of FW205 the OECD and FAO published their annual long-range forecasts of agricultural commodity market developments to 2024. While price forecasts over a decade should be taken with a healthy dose of scepticism, it is nonetheless of interest to see what these international forecasters predict. These forecasts are made on the basis of specific assumptions about future oil prices, exchange rates as well as supply and demand developments and trade agreements.

Last December the Commission also published its annual update of its price forecasts for EU and global markets forward to 2024. Both the OECD-FAO and Commission forecasts use the same underlying economic model (the AGLINK-COSIMO model) but not necessarily the same assumptions. Also the Commission forecasts in the table below refer to projected EU market prices (in euro), while the OECD-FAO forecasts are sometimes for global market prices (in US dollars).

Despite these differences, the underlying message from the two projection studies is the same. Neither expects much further uplift in nominal prices for the main commodities produced by the Irish agricultural sector. While cheese prices are expected to strengthen slightly, this is more than offset by the anticipated fall in the nominal price of beef. Despite the hype around buoyant dairy markets in the future, the EU Commission projects that the EU-wide nominal milk price, at 36.3c/litre, will be exactly the same in 2024 as in 2012-2014.

It therefore seems unlikely that increases in commodity market prices will be of much help to the primary sector in meeting its aspirational target of a 65% increase in the value of primary output over the twelve years to 2025. In practice, static nominal prices mean that real farm prices are likely to fall over the coming decade. Energy and fertiliser prices are expected to increase from their current low levels, so the overall economic environment may not be as benign for farm production as it has been in recent years.

CAP payments are also fixed in nominal terms, and will decline in real terms, to 2020. The outlook for these payments beyond 2020 is uncertain as the report acknowledges. Thus, while the primary production sector includes, in addition, both seafood and forestry, I conclude that the primary sector headline target seems far out of reach.

Nominal prices for processed agricultural commodities, such as prepared consumer foods and drinks, will increase at a faster rate than commodity prices because the drivers of the value-added margin between commodity and wholesale prices differ from the drivers of commodity prices. There is also the expectation that the focus on high-end products backed up by strong environmental and sustainability credentials will help to raise unit value returns at a faster rate than for food prices in general. Higher nominal prices as well as increased throughout will thus help the agri-food sector as a whole to meet its aspirational targets for growth in the value of exports and value added.

A lot will depend on whether the recent remarkable growth in food industry output is due to one-off factors (such as the sharp decline in the value of the euro relative to sterling as well as the US dollar since 2010 which has greatly helped food industry competitiveness on the important UK and US markets) or whether it can be sustained over time. However, I would be more confident that these targets can be met than I would be for the target for the output of primary production.

The key recommendations

Whether the targets are met or not depends not only on growth opportunities but also on the actions taken by farmers, processors and government. As noted, more than 350 recommendations directed to these groups are included in the FW2025 strategy, although many are exhortatory in nature.

There is a refreshing focus on ‘real’ drivers of sustained competitiveness, such as innovation, improved breeding and marketing, and less emphasis on calls for additional subsidies or public expenditure to drive growth, even if the latter are not entirely absent. It would be desirable if the report had added a price tag to the various proposals which would require increased public expenditure, and even more desirable if the committee had been able to identify sources of funding from within the agriculture budget.

Interestingly, there are no proposed growth actions in the chapter on growth opportunities. Instead, emphasis is placed on improving the efficiency of production as an important element in the drive for sustainable intensification. ‘

The focus at farm level is on more extensive measurement (further rollout of the Carbon Navigator initiative, more farmers undertaking grass measurement, more farmers making use of profit monitors), knowledge transfer leading to more sustainable farm management practices (more use of the Pasture Base Ireland tool to help improve soil fertility, more farmers enrolled in knowledge transfer programmes), actions to improve animal productivity, health and welfare (more use of genomics to improve the rate of genetic improvement, greater participation in the Beef Healthcheck programme) and greater environmental awareness (increased participation in the Beef and Lamb Quality Assurance Scheme).

At the food industry level, the focus is on added value through R&D (target for increased industry expenditure on R&D), actions to improve the reputation of Irish produce in the international marketplace, (development and enhancement of the Origin Green programme, better links between food and tourism), measures to enhance stability in the supply chain (greater use of fixed price contracts and contractual supply arrangements, better communication on marketplace developments along the supply chain) and attracting more private investment into the prepared consumer foods sector.

These are all sensible measures, although many of them are not new suggestions. To understand FW2025, we need to recognise that it builds on a series of ongoing government programmes and public expenditure commitments where much of the real action in terms of incentives takes place.

At primary sector level, these include the delivery of direct payments under CAP Pillar 1, various measures under the Rural Development Programme 2014-2020 under CAP Pillar 2, the Seafood Development Programme 2014-2020 part-funded by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund, the Bioenergy Action Plan and the revised Forest Policy adopted in 2014. For the food industry, there are also a range of incentive schemes in place run by the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment. An important missing element in this architecture is the National GHG Mitigation Plan for the agricultural sector which is still under development.

FW2025 does not address the most important obstacles to growth in the primary and food sectors. Last year, Professor Alan Renwick with colleagues in UCD and Teagasc published a report on innovation in the agri-food sector. They concluded that the strongest barriers to innovation were at the farm level and related to the structure of farm businesses, the age structure and the related issue of lack of land mobility. None of these issues are explicitly addressed in this report. At food industry level, the role of structural change as a driver of competitiveness is underplayed, possibly because of the representative nature of the group and the competing interests at play.

For this reason, it is hard to position the FW2025 report. It describes itself as having been conceived “as providing both vision and strategy for the future development of the sector”. Nonetheless, its recommendations, while valuable in and of themselves, address only a small sub-set of the issues and challenges affecting the sector. It takes for granted, and builds on without explicitly making reference to, a whole range of other programmes, initiatives and schemes which will determine how the sector responds to the growth opportunities that emerge.

My take to explain this paradox is that this report is food industry-driven. It is not really concerned with the messy details of how to increase primary production in agriculture, fisheries and forestry. In this respect, the over-blown target for increased primary sector output seems thrown in as an afterthought – the real targets are the increases in food industry exports and value added.

Where the report does discuss primary production, it is mainly through the lens of ensuring farmers, fishermen and foresters live up to the processing industry’s requirement to be able to demonstrate its environmental and sustainability credentials. Increasing the numbers of farmers measuring their grass growth, or participating in the Carbon Navigator or improved breeding programmes, is recommended not because it will increase production (though this may be a consequential side-effect) but because by improving efficiency it helps to build the sustainability claims of the food industry. And this is no bad thing.

The environmental assessment

This ambiguous nature of FW2025 does not make it easy to perform a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). On the one hand, the strategy has been defined with the expectation of substantial growth in output, both at primary production and processing levels. On the other hand, the report itself is more about positioning the food industry to take advantage of this growth by focusing on high added value products, emphasising its environmental and sustainability credentials. So what should be the focus of the Strategic Environmental Assessment – on the environmental implications of the underlying growth, or on the measures proposed in the report to underpin and make more credible the industry’s claim to environmental sustainability?

The published draft Environmental Report comes down firmly on the side of the second alternative. Its approach is to take each of the individual recommendations, or ‘actions’, grouped into categories and then to assess the potential impact of each group of actions on 17 Strategic Environmental Objectives in the form of a matrix.

As an example, the actions related to the dairy sector are divided into 6 categories and sub-categories which, mapped against the 17 Strategic Environmental Objectives, gives a matrix with 102 potential environmental impacts. Of these, only 5 are judged to be slightly negative, all related to actions grouped in the category ‘grassland and soil management’. Some potentially negative consequences are foreseen for water quality, habitats and species, as well as higher GHG emissions because increasing soil fertility is likely to involve increased use of fertilisers.

The fact that dairy cow numbers might expand by up to 30% (which is suggested as a possible outcome under the high expansion strategy) is not deemed relevant to the SEA and is therefore not assessed. The expected negative increase of GHG emissions is put down to increased use of lime, and not increased dairy cow numbers. For the dairy sector, 97 of the 102 potential environmental impacts of the strategy will be either non-existent or positive.

Why agricultural expansion is ignored

It will be hard for environmental NGOs to understand that an environmental assessment of a strategy which is predicated on the biggest acceleration of agricultural growth for thirty years sidesteps this issue entirely, even if strictly it does adhere to its brief of assessing the environmental impact solely of the actions proposed in the strategy itself. How was this achieved?

In preparing any Strategic Environmental Assessment, a requirement is that it should normally involve comparisons between alternative plan or programme scenarios. In this case, three scenarios were considered:

-

A Base Case Scenario or ‘business as usual’ scenario which involved continuation of the rate of changes in production levels seen over recent years to generate a moderate increase in output through improvements in technology and management techniques:

-

A Base Case + Scenario which takes account of the elimination of milk quotas and the projected expansion in dairy cow numbers planned by farmers and the processing industry, “leveraged by substantial increases in the use of best technology facilitated by enhanced knowledge transfer programmes”-

-

A Sustainable Growth Scenario (essentially that adopted in FW2025) which incorporates a set of “guiding strategies” on top of the Base Case + Scenario to mitigate potential environmental impacts. These include:

• Investment in environmental monitoring systems;

• Investment in science based research which demonstrates that Irish production systems are environmentally sustainable;

• The rollout of new technologies and production processes;

• The transfer of knowledge to all actors in the supply chain so that necessary productivity efficiencies are achieved.

Effectively, the Sustainable Growth Scenario is compared to the Base Case + Scenario and not to the Base Case scenario. Thus, the expansion of agricultural, fisheries and forestry output is assumed to be already underway, leaving the SEA to concentrate only on evaluating the environmental impact of these guiding strategies.

This approach may be technically in compliance with the terms of reference of the SEA, but it is hardly adequate as a guide to policy. Indeed, many will see it as a sleight-of-hand to obscure an important debate over the extent to which increased agricultural output can be achieved within the country’s environmental boundaries and targets.

What should be done?

My view is that it makes full sense to pursue the expansion of agricultural and food industry output provided this takes place on the basis of the true competitive advantages of the sector (and not on the basis of public subsidy) and provided that the environmental consequences are addressed and fully internalised into decision-making at farm and industry levels. The FW2025 recommendations are sensible and should be pursued, but as we have seen they leave out much of the picture.

The draft Environmental Report recommends a programme of monitoring the environmental performance of the FW2025 strategy. It further recommends that an environmental sub group be convened during the duration of the plan to review the ongoing environmental performance of the plan. This subgroup would have the capacity to reconsider new and additional mitigation and monitoring if considered appropriate during the duration of the plan.

Monitoring only makes sense if the full environmental consequences of the agricultural expansion are taken into account, and not just those associated with the recommended actions contained in the FW2025 strategy. In other words, the fiction underlying the draft Environmental Report that agricultural expansion is something that was pre-existing and should not therefore be considered in the evaluation should be dropped.

To assist the monitoring a full environmental evaluation of the likely consequences of agricultural expansion should be commissioned, together with the preparation of appropriate mitigation strategies. For this purpose, the environmental sub-group should be formed now rather than later. Its first task should be to commission a proper overview of the likely environmental challenges inherent in the expansion strategy behind FW2025.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

You say:

“by improving efficiency it helps to build the sustainability claims of the food industry. And this is no bad thing.”

Surely you realise that this is a deeply questionable statement buying into the highly misleading rhetoric of Ireland’s Dept of Agriculture, the agri science body Teagasc and the livestock dominated Irish agri-food industry. Impacts on the environment depend on the total quantity of pollutants released, the environment does not ‘care’ how ‘efficiently’ we produce that quantity. Efficiency means the amount of something used or produced per unit of product. The footprint quantity of what is used or produced is the product of the ‘efficiency’ and ‘units produced’. It really is that simple.

How can this nonsense of equating efficiency with footprint and ignoring production continue to be perpetuated? The Carbon Navigator would be useful if Irish agriculture was operating within an enforced and annually decreasing cap on GHG emissions. But it is not. Agriculture and transport are responsible for Ireland’s missing the 2020 non-ETS target. Transport users are paying a carbon tax (which clearly is not high enough) and consumers of high GHG food (ie beef and dairy) are paying nothing for using the atmosphere as a waste dump.

Result: the Carbon Navigator enables efficiency improvements resulting in more cost savings for farmers, allowing more investment in increasing production resulting in greater carbon emissions. You don’t have to look hard to find examples of this, in the Irish Farmers Journal for example.

Increasing efficiency will not decrease the footprint unless the efficiency improvement is great enough to outweigh any increase in production level. This should be obvious to an eight year old yet our government and our leading agricultural science body Teagasc continue to espouse the indefensible. Origin Green is similarly compromised – also allowing self-assessment of baselines and leaving out any inconvenient categories such as total emissions or total pollution. You pointed this out in your IIEA presentation yet you pass over it in this article.

Focusing on efficiency and forgetting to multiply by production to show actual impact is unacceptable in any sustainability assessment. It is total impacts that count and reductions in these are what the agri industry has to demonstrate in expanding production, unless we are simply accepting that ‘sustainable’ is just another word for profitable.

Paul Price @swimsure

@Paul

Thanks for your comment. The ultimate goal is that the price of everything that consumers buy, whether energy, food, transport or clothes, reflects the full cost of production, which includes the cost of negative effects on health and environment. This also applies to milk and meat production. Meat and milk production are important in Ireland because they exploit a natural resource (grass) for food production. The experience of fifty years of subsidies mean that we don’t do this very effectively at the moment, so I welcome any moves which would result in greater efficiency in this production.

Meat and milk production also play an important role in generating incomes (even though much drystock production does not currently cover its costs, and many farmers could increase their income by switching to biomass production including afforestation, as I argued in the presentation to which you refer http://capreform.eu/levelling-the-playing-field-for-land-based-enterprises-in-ireland/). My view is that support for climate policy rises when people are better off and falls when incomes are falling. Therefore, greater production efficiency feeding into higher farm incomes is also fully consistent with a more active climate policy.

This post did not address climate policy specifically, I had discussed that in the earlier post. But I agree with you that it is total impacts that count. But that is not a reason for not improving efficiency where it makes sense.

@Alan

Thanks for taking time to reply to my comment. I was reacting (critically) to that one line and should also have positively said that that your summary of the environmental assessment problems is very detailed and very helpful. It will indeed “be hard for environmental NGOs” [or anyone with analytical sense] “to understand that an environmental assessment of a strategy which is predicated on the biggest acceleration of agricultural growth for thirty years sidesteps this issue entirely”:

To reply to your response.

I too welcome greater efficiency but not if it comes at the cost of yet greater environmental damage that is clearly decreasing the much-vaunted level of sustainability being claimed by the agri-industry and promoted by government. I pointed to climate costs as one indicator, much increased fertiliser use (up 19% in one year from 2012 to 2013) would be another concern from Food Harvest 2020 that is causing both increased climate and water pollution impacts.

If these costs were internalised so that the consumer paid for them then as you say that would be good. But there is no sign from Government or industry that this will occur. Origin Green could be a start in the right direction but the unjustifiably overblown claims being made (for example at the Milan Expo happening now) suggest that greenwash is more important than substance. If they did pass on the costs to the consumer then the revenue raised through pollution levies could then fund the very transitions you described so well in your presentation. Would this makes sense in every way for the farmers and for the environment?

You are no doubt correct that “support for climate policy rises when people are better off and falls when incomes are falling”. (Global warming though continues whether incomes fall or not, sadly the atmosphere of course does not ‘care’ about our incomes and in the long run will likely unsustainably damage incomes itself.) However, your argument that, “Therefore, greater production efficiency feeding into higher farm incomes is also fully consistent with a more active climate policy”, does not make sense unless you mean an ‘apparently’ active climate policy. An active climate policy is not the same as an effective one.

You agree that it is total impacts that count and therefore one cannot and must not detach ‘efficiency’ from ‘production’ when the one multiplied by the other gives the total impact. And as you know many of these impacts are cumulative because they exceed natural absorption.

Yes, improving efficiency makes sense but, once again, by repeating this in your reply without immediately stressing the critical need to include the production units that make the efficiency (in footprint per unit production) add up to total impacts I think you are repeating the misleading focus I am commenting on. It would be very good if this elementary point was made more clear by everyone who has real concerns about sustainability, especially government departments and agencies who have a responsibility to give impartial advice and evidence for public decision-making.