Even though the latest changes in the CAP regulations only came into force on 1 January this year, attention is already beginning to focus on potential further changes to the CAP after the end of the current programming period 2023-2027. The Commissioner for Agriculture Janusz Wojciechowski started the ball rolling back in June. In his contribution to the European Parliament debate on the Mortler Report on ensuring food security and long-term resilience of EU agriculture which, inter alia, called on the Commission to present a holistic plan to ensure food security for the EU, he commented:

I am in full agreement with this. We need a plan presented by the Commission to ensure food security in the European Union, a plan that also takes into account the role of the European Union in global food security. This will also be a plan for elements of the Common Agricultural Policy after 2027, and I intend to prepare and present such a plan in the coming months, certainly still in 2023. (bolding added)

The Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) together with several members of the Think Sustainable Europe network of think tanks recently published a vision paper written by David Baldock and Harriet Bradley which sought to flesh out some ideas on what the post-2027 CAP might look like. I participated in several workshops that preceded this publication and also in the launch event. In this post, I would like to reflect on several themes that are highlighted in this paper.

Setting the scene

The IEEP policy paper is clear that there are multiple dimensions to agricultural policy. It acknowledges the importance of food production and that farming, together with other land uses, supports rural livelihoods over a large area of Europe. At the same time, it emphasises the need for more rapid progress to a more sustainable and resilient agriculture and land use sector.

It highlights the way in which external drivers may impact these various dimensions, including future market conditions, the prospect of further EU enlargement to include Ukraine, geopolitical instability, accelerating technological change, socio-demographic change, and increased weather instability. The paper also recognises that already agreed legislative targets, such as the increased LULUCF sink by 2030, as well as forthcoming changes to EU legislation, including setting new climate targets for 2040 and enacting Farm to Fork Strategy targets into law, will need to be addressed as part of a future CAP. Furthermore, the growing demand for land for nature, for energy production, as a carbon sink, as well as for food production will provide both challenges and opportunities for farmers.

The paper thus sees “a critical need to provide incentives for farmers and land managers, to support them in implementing sustainable practices and systems and to compensate vulnerable groups from negative shocks as part of a just transition”. For this reason, the focus of the paper is on future funding mechanisms including the use of CAP funds by Member States and how they might be better allocated.

The IEEP vision

The paper goes on to identify several shortcomings in the CAP even after the most recent reform. These include the continued concentration of CAP funds on untargeted decoupled payments to provide income support, insufficient delivery on sustainability, and a lack of ambition among Member States to use the increased flexibility and autonomy they have under the new delivery model to prioritise ambitious environmental interventions given the competing priorities for this funding. Based on this analysis, the paper identifies three main needs:

- Repurposing direct payments in their present form to focus on paying for public goods and environmental services;

- A stronger priority for environment and climate goals, and removing tensions with competing or conflicting priorities;

- A stronger role for environmental and climate authorities, which are directly responsible for delivering climate and biodiversity goals and consequently motivated to deliver policies designed to deliver the required outcomes effectively.

The idea that CAP direct payments should be repurposed to payments for public goods and environmental services is of course not new. To some extent it has been reflected in changes introduced in the latest revision of the CAP. Where this paper breaks new ground, in my view, is that it recognises the need to accompany this repurposing by specific transition aid. It also foresees that financing both sustainable land management on an ongoing basis and a just transition will require additional funding beyond what is available for the current CAP.

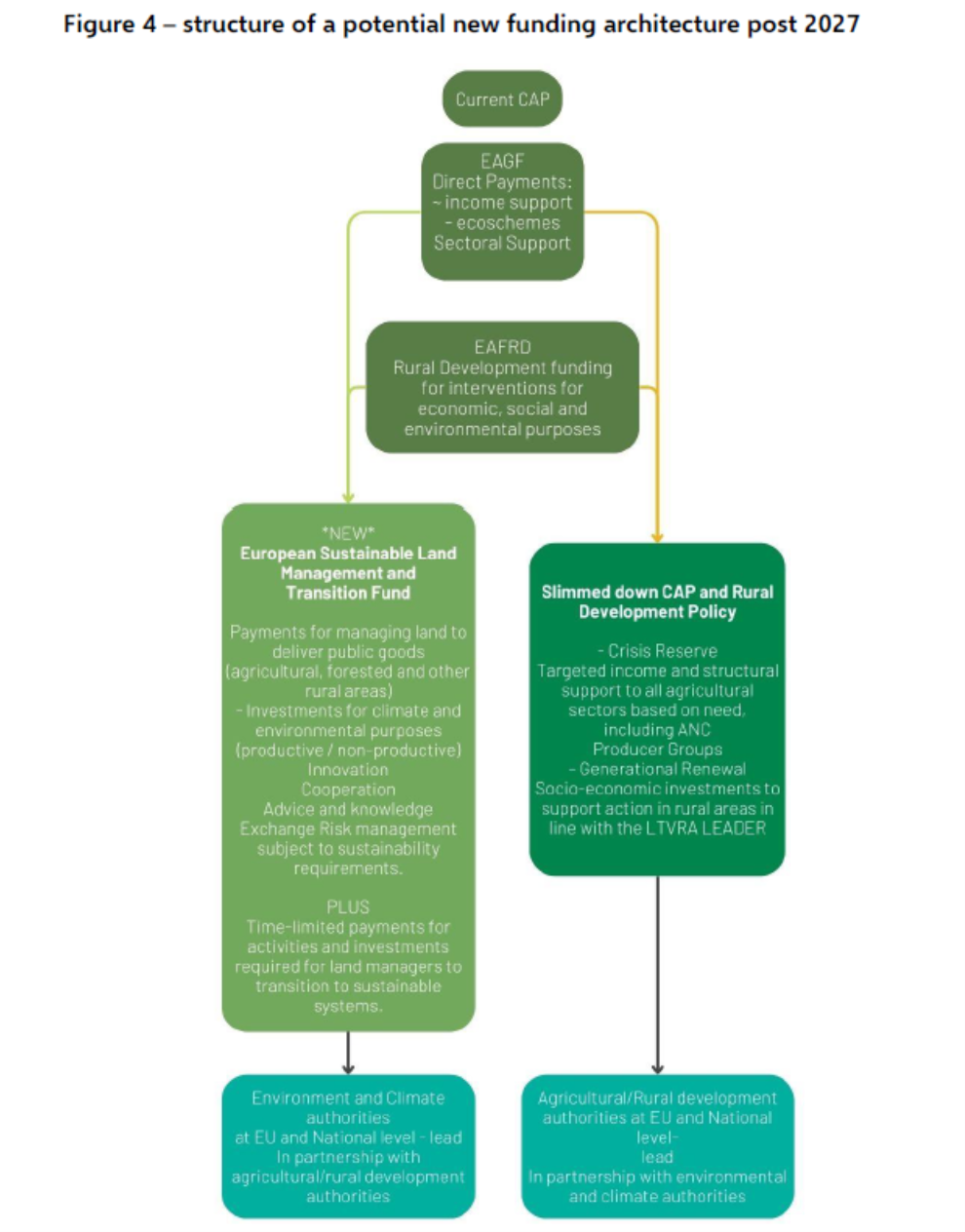

However, it is sceptical that this shift can be undertaken in a sectoral policy that is dominated by agricultural interests in the Council, Parliament and Member States. It therefore calls for a new funding architecture to carve out a new fund from the existing CAP, to be called the European Sustainable Land Management and Fair Transition Fund, while a slimmed down CAP would continue to fund remaining agricultural policy priorities including rural development, crisis aid, and residual targeted income support. The critical change with the new Fund would be that the authorities responsible for meeting environmental and climate targets would have a central role in managing the spending assigned to support this goal. The authors are careful to point out that the proposal is not designed as a blueprint but as a basis for further discussion.

We now examine these three central elements in the proposed vision in greater detail.

An explicit role for transition aid

The policy paper proposes a role for transition aid to support farmers for a limited time period to adjust to new sustainability requirements arising from both legislation and changing market expectations. Some of this may be investment aid, but it also includes ‘de-risking aid’ and ‘cessation/diversification aid’. The idea with de-risking aid is that “switching to more sustainable forms of agriculture, such as regenerative systems, can involve a period in which yields may drop, trial and error experiments may be needed, the right equipment identified and acquired, and new skills developed. There may be a higher risk adjustment period of several years which can deter farmers from making management changes but could be addressed by targeted aid”.

Cessation or diversification aid is intended to contribute towards a just transition in cases where production needs to be significantly reduced or stopped entirely, or where land use change is required, for example, where livestock numbers need to be reduced, or where organic soils need to be rewetted. There will also be cases where the elimination of untargeted direct payments may cause individual hardship cases, given the way direct payments support land prices and underpin bank lending, and where public good payments may not be sufficient to provide a satisfactory alternative. Experience in the UK (England) with the phasing out of direct payments will provide valuable lessons in this regard.

Member States can already use CAP funds to support some elements of this proposed transition aid. However, CAP funds cannot be used to pay farmers for practices that are required by law, or as a condition for receiving CAP payments, which could limit the provision of de-risking payments. However, specific derogations can be foreseen, as for example in the draft Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation (SUR), where in the Commission proposal Member States could use CAP funding to cover costs of any obligation for farmers and other users stemming from the proposed regulation, including compulsory farming practices imposed under the crop-specific rules for IPM, for a transition period of 5 years (Article 43 of the draft SUR proposal).

What is proposed here is something akin to the arrangements in place to support organic farming, where in addition to ongoing support there is also a conversion payment to cover the loss of income in the initial period when a farmer is converting to organic production but is not yet able to benefit from a price premium by selling the produce as organic. Presumably, a list of desirable eligible practices where there is a potential income risk for farmers engaging in the transition could be established in legislation, which would allow Member States to support these farmers through a de-risking payment for a time-limited period before payments for the provision of environmental services ramped up.

An explicit role for environmental authorities

There is a strong political economy rationale for removing funding for the green transition from the agri-centric CAP to a new fund that would be more under the control of environmental authorities. It reflects lessons learned from the gap between rhetoric and agenda-setting, on the one hand, and implementation, on the other hand, with respect to the food system transformation generally in the EU. I and co-authors have explored the reasons for this gap in this chapter in a recent book published by Oxford University Press entitled The Political Economy of Food System Transformation. We found that the success in creating a more ambitious agenda for food system transformation in the EU was due to the involvement of a wider range of actors in shaping agricultural policy priorities than in the past. Implementation, however, has been much more contested, in part, because of the more prominent role of established interests, for example, when allocating resources under the national CAP Strategic Plans.

The main justification put forward for creating a new sustainable land management and fair transition fund is that the authorities responsible for meeting climate and environmental targets would be primarily responsible for the design of interventions and the use made of these resources. In practice, however, it is not clear how this new governance structure could be implemented.

At EU level, governance would change only if the management of the legislation establishing the fund were the responsibility of the Environment Council in the Council of Ministers (rather than the Agriculture and Fisheries Council) and the responsibility of the Environment Committee in the European Parliament (rather than the Agriculture Committee). As the focus of the new fund would be on sustainable and resilient land management, there would be a strong territorial tussle between these various formations as to who should lead on the legislative file. The governance dilemma would be even more pertinent at the national level as the EU is not able to dictate which government ministry should be responsible for administering the fund. Also, as the policy paper itself admits, the focus on land management means the environmental authorities would anyway need to involve agricultural, regional and established delivery agencies in Member States and regions as appropriate.

Member States were required to follow certain procedural requirements (Article 106 of the 2021 Strategic Plan Regulation) when drawing up their national CAP Strategic Plans. One of the requirements was to ensure that “the public competent authorities for the environment and climate are effectively involved in the preparation of the environmental and climate-related aspects of the CAP Strategic Plan”. It would be valuable to commission a research project to assess the extent to which this happened in practice. How were the environment and climate authorities involved? What time was given for them to prepare their contributions? What evidence is there that these contributions made a difference to the final outcome? The views of the authorities themselves on these questions would be very illuminating.

An adequate budget to support the transition

The IEEP paper is explicit that “a shortage of funding for a transition is impeding progress, with the successor to the current CAP a major opportunity to address this. The setting and implementing of new regulatory requirements and targets that will put new demands on the sector needs to be matched by an adequate level of external funding as well as adjustments in the market”.

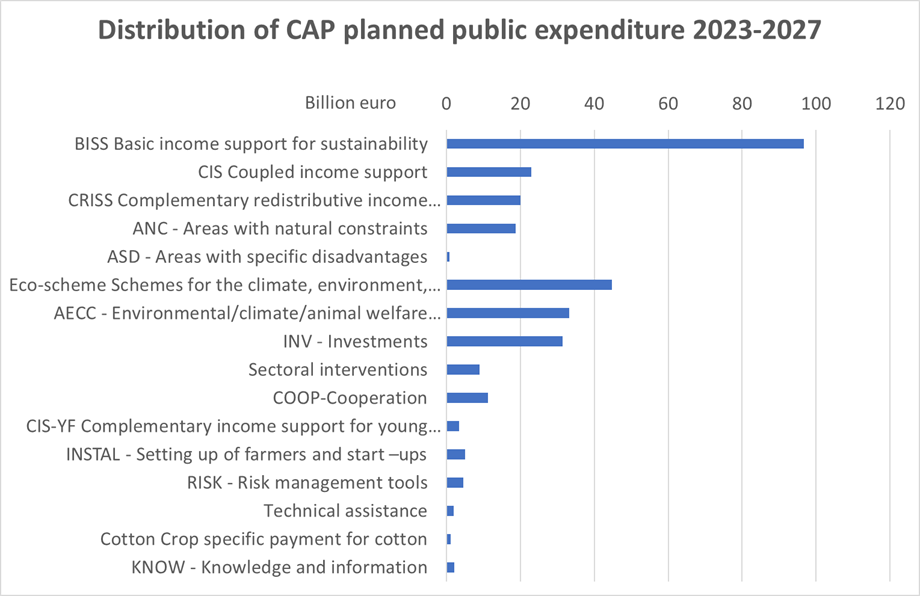

Total planned public expenditure under the CSPs is made up of €264 billion of CAP funds and €43 billion of national co-financing for a total of €307 billion in public financing over the five-year period. The breakdown of CAP public spending is shown in the following figure. Under half of the CAP budget is now allocated to income support, defined as the sum of BISS, CIS and CRISS. This amounts to planned expenditure of €140 billion, or 45% of the total. This compares to €76 billion for eco-schemes and agri-environment-climate interventions together.

Income support payments increase to €158.5 billion if ANC payments are included as income support, bringing the share to 52% of CAP public spending. While ANC payments are indeed income support, they are a voluntary payment intended to compensate farmers for disadvantages due to natural or other specific constraints with the payments calculated as the difference in incomes and costs between constrained and non-constrained areas. Although 59% of the EU’s Utilised Agricultural Area (UAA) is designed as ANC, payments are only made of 29% of UAA in the national Strategic Plans (Commission, 2023). The paper assumes that these payments would largely be continued under any restructuring of funding arrangements in a new CAP.

The IEEP policy paper does a back-of-the envelope calculation to estimate how much additional funding could be made available by repurposing CAP spending. It includes 85% of basic income support (the paper accepts there may well be a case for maintaining some limited direct income support for smaller farms) and 100% of coupled support, investment aids and risk management. Together with existing environmental spending, it estimates that €38 billion could be available annually as funding for the new sustainable land management and fair transition fund. This may already be an overestimate as it makes no allowance for the loss of enhanced conditionality when income support payments are phased out. While some of the GAEC conditions might become statutory requirements, as they already are in some Member States, for others it will be necessary to pay farmers for compliance either through eco-schemes or AECMs, which will diminish the amount of money available for ‘new’ measures to support the green transition.

The paper quotes some estimates of what sustainable land management might cost. Given that a repurposing from untargeted direct payments to payments for environmental services and a fair transition would be phased in over a period of years, it concludes that “such a phased transfer would not generate a sufficient flow of funding in the early years in particular. This would be the period during which demands for transition funding would be especially acute given the scale of change needed in the late 2020s and early 2030s.”

This is clearly a controversial issue. Commissioner Wojciechowski is on record arguing that the current CAP budget is insufficient to guarantee food security, focusing particularly on the need to increase the agricultural reserve. Former Vice-President Timmermans, on the other hand, just prior to his return to Dutch politics, argued that there is no need to increase the CAP budget to smooth the green transition, provided that the existing money is spent in the right way. He also felt it was unrealistic to expect Member States to be willing to provide additional money for farmers given the other, and increasing, demands on the EU budget in the next MFF period.

The IEEP policy paper makes the case that there could be a willingness to find additional resources to support farming in the green transition, provided that there is a clear commitment to spend the money differently, and that this would be best demonstrated by setting up new funding and governance structures. However, it is also realistic that additional funding will also have to come from outside the MFF. It calls for prompt examination of options to raise supplementary funding particularly for the period of adjustment.

Conclusions

The debate on the shape of the CAP in the next programming period is already underway, even though the ink is hardly dry on the CAP Strategic Plans that started implementation on 1 January this year. According to this policy brief prepared by the SHERPA Horizon 2020 project in April 2023, the Commission will formally launch the official public debate during the DG AGRI Outlook Conference in December 2023, followed by an official public consultation on the next proposal in Q1 of 2024 and with a planned publication of a legislative proposal in July 2025.

At the same time, the CAP Strategic Plans Regulation itself contains important dates in its multiannual evaluation plan (Article 141). By end of this year (31 December 2023), the Commission should prepare a summary report of Member States’ CAP Strategic Plans which shall include an analysis of the joint effort and collective ambition of Member States to address the specific objectives set out for the CAP and specifically the three environmental objectives.

By 31 December 2025, the Commission should submit a report assessing “the operation of the new delivery model by the Member States and consistency and combined contribution of the interventions in the Member States’ CAP Strategic Plans to achieving environmental and climate-related commitments of the Union”. When necessary, the Commission shall issue recommendations to the Member States to facilitate the achievement of those commitments.

By 31 December 2026, the Commission should undertake an interim evaluation to examine the effectiveness, efficiency, relevance, coherence and Union added value of the EAGF and the EAFRD, taking into account the indicators set out in Annex I of the CAP Strategic Plans Regulation.

Member States are also expected to carry out their own independent evaluations of their CAP Strategic Plans during implementation and ex post to improve the quality of the design and implementation of the Plans. Their evaluation plans should be submitted to the monitoring committee no later than one year after the adoption of the Plans.

Based on evidence in these evaluations as well as on other information sources, the Commission should present a report on its interim evaluation, including first results on the performance of the CAP, to the colegislators by 31 December 2027.

The Commission should also carry out an ex-post evaluation to examine the effectiveness, efficiency, relevance, coherence and Union added value of the EAGF and the EAFRD. While no date is specified for this ex-post evaluation, it would feed into the second report including an assessment of the performance of the CAP to be presented to the colegislators by 31 December 2031.

Based on these timelines, the Commission will present its legislative proposal for the next CAP without the benefit of the evaluations that are programmed for later. The Commission will only have available its own summary report of how Member States have used the flexibility of the new delivery model to allocate CAP resources and the level of ambition they have set for the three environmental objectives to be completed by 31 December 2023. On this basis it may well feel inhibited in proposing radical changes to the current CAP. We might even see a recommendation that the current CAP rules should be extended for a transitional period into the next MFF programming period.

The question for DG AGRI inside the Commission and for agricultural interests outside the Commission is whether a proposal more focused on supporting farmers who embark on the green transition has more potential to safeguard or increase the CAP budget in the MFF proposal than a status quo proposal. Overshadowing this debate will be the question whether the CAP budget structure needs anyway to be overhauled in view of prospective accession of Western Balkan countries including Ukraine.

Ultimately, these are political decisions that will be taken by the European Council (when agreeing on the size and distribution of the next MFF) and the European Parliament. Here the outcome of the European Parliament elections in June 2024 and any changes to the political composition of the Parliament will be critical, as the next Commission President and his or her political guidelines must be approved by the Parliament by an absolute majority. Food and agriculture will certainly figure in those guidelines, so already at this point we will have a fair idea of which way the wind is blowing and what the Commission proposal is likely to be.

The focus on the shape of the CAP in the next programming period should not distract from the fact that there is plenty of scope for Member States to adjust their CAP Strategic Plans in this programming period. Member States can amend these plans once a year. Specifically, where there is an amendment to one of the pieces of environmental and climate legislation listed in Annex XIII of the CAP Strategic Plans Regulation, they are required to assess whether an amendment to their Plan is necessary and to submit a reasoned explanation for their decision to the Commission (Article 120). There is thus scope at national level to introduce the changes envisaged in this IEEP policy paper, but unilateral national moves will always be met by the criticism that they put farmers in the implementing country at a disadvantage relative to farmers in neighbouring countries with less ambitious policies.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Picture credit: Wikipedia, used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 generic license.