The European Council leaders at their meeting on 17-18 October 2019 failed to make progress in advancing discussions on the next Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF) due to start on 1 January 2021. The Council’s conclusions noted that: “Further to a presentation by the Presidency, the European Council exchanged views on key issues of the next Multiannual Financial Framework such as the overall level, the volumes of the main policy areas, the financing, including revenues and corrections, as well as the conditionalities and incentives. In the light of this discussion, it calls on the Presidency to submit a Negotiating Box with figures ahead of the European Council in December 2019”.

The European Council’s conclusions in June 2019 had anticipated a more ambitious timetable. At that meeting, it called on Finland’s Presidency “to pursue the work [done under the Romanian Presidency] and to develop the Negotiating Box. On that basis the European Council will hold an exchange of views in October 2019, aiming for an agreement before the end of the year.” It is now clear that this ambitious timetable will not be met.

Indeed, originally, the Commission had hoped that the MFF would be in place prior to the European Parliament elections in May 2019 (an ambition supported by the Parliament) in order to avoid delays in implementing EU programmes with potential to spur the European recovery.

The European Council had before them a two-page discussion paper prepared by the Finland Presidency, based on a questionnaire it circulated to Member States last July and bilateral consultations (thanks to Euractiv for making this paper available). The paper says Member States differ on the overall contribution to the future MFF, with the range between 1.00% of the EU27 GNI, and the Commission’s proposal of 1.11%. The paper also says that while the modernised approach proposed by the Commission has received broad support from Member States, many of them also highlighted the importance of continued support for Cohesion policy and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

In this post, I look at the implications of the Finland Presidency paper for what it tells us about the state of play of the MFF negotiations at this point in time, as well as what it might mean for the absolute size of the CAP budget in the next MFF programming period. It seems that the Presidency proposal could point to a small increase in the size of the CAP budget in nominal terms by between 0% and 6% in the next MFF period compared to the Commission’s draft proposal, but many uncertainties remain.

Why agreement on the MFF is difficult

For many reasons, the difficulties Member States have in progressing the MFF negotiations should not surprise. As summarised in the conclusions of the October 2019 Council quoted above, the issues to be addressed are enormous, complex and intertwined. They raise fundamental questions regarding what the EU budget is for and what the money should be spent on; how the EU budget should be financed and whether new sources of revenue should be introduced; whether and how the EU budget can play a stabilisation function particularly in the context of managing the single currency; as well as more recent debates around conditionalities and particularly whether a requirement to observe the rule of law should be made a condition for the receipt of EU funds.

Looming behind these discussions is the perennial division between net payers and net contributors to the EU budget which is played out particularly in the debate around the overall size of the EU budget.

This debate is further sharpened on this occasion by the withdrawal of the UK from the EU, given that it has been the second largest net contributor to the EU budget. Brexit not only leaves a financing gap which the remaining Member States have to decide how to cover, whether through expenditure cuts or increasing their budget contributions. It also calls into question the rationale for the system of rebates that has grown up as a way of securing unanimous agreement to the MFF in the past, but which has undermined the transparency and, some argue, the fairness of the resulting outcomes.

The Commission’s suggestion to remove all rebates in its draft MFF proposal exacerbates the impact on the remaining net payers of its concurrent proposal to increase the size of the MFF, whatever the individual merits of these proposals on their own.

At the end of the day every Member State has to walk away feeling that they have won something. The decision has to be unanimous (unless the European Council unanimously agrees that the Council can act by qualified majority in adopting the MFF Regulation). Furthermore, the European Parliament must approve the MFF Regulation (which sets the ceilings on particular headings of expenditure) and must be consulted on the Own Resources Decision (which sets the maximum limit for payment appropriations in any year). Not only that, but the Own Resources Decision has also to be approved unanimously by national parliamentary bodies as well (by one count, this requires 42 separate votes across the EU). It took two-and-a-half years before the Own Resources Regulation for the current MFF passed all of these hurdles.

This fixation on net budget balances – the ‘juste retour’ principle – as the criterion for declaring ‘success’ in the MFF negotiations is repeatedly criticised for ignoring the wider benefits of EU membership (the Commission makes this case in this factsheet for the single market) as well as, more narrowly, the European value added of the budget expenditure on its own.

The problem is that even accepting the validity of these arguments leaves unclear what is a fair distribution of the costs of obtaining these benefits. It is thus not surprising that Member States fall back on the calculation of net budget transfers as a proxy measure and that this is the criterion used by national parliaments and national taxpayers to evaluate the reasonableness of the MFF outcome when finally agreed.

On this occasion, a group of net payers known as the ‘Frugal Four’ – Austria, Denmark, Netherlands, and Sweden – have rejected the Commission’s draft MFF proposal to raise the level of commitment appropriations from 1.0% of GNI to 1.08% of GNI (from 1.03% to 1.11% if the European Development Fund is included as the Commission has proposed) and have insisted on retaining the ‘political ceiling’ of 1.0% of GNI.

This group has now been joined by Germany to become the ‘Frugal Five’. Germany’s hard line on the overall size of the EU budget was communicated to the Finnish Presidency in response to a series of questions in July designed to elicit Member State positions. According to Politico Europe’s account of the German response, the government replied that “We will conduct the MFF negotiations on the basis of 1% of the EU27 GNI”. The German Finance Ministry has calculated that, even on this basis, the German contribution to the EU budget would increase by €10 billion annually. The German Chancellor, in an address to the Bundestag just prior to the European Council meeting, said even this increase was unacceptable and demanded that the rebate that limits Germany’s net contribution to the EU budget as a result of the UK rebate should be kept in place.

This hard-line position appears to contrast with the forward-looking, historically-aware speech by the former German Foreign Minister, Sigmar Gabriel, at the EU budget conference Shaping our Future: Designing the Next Multiannual Financial Framework in January 2018 which lambasted the obsession with net budget balances also in Germany and called on the Commission to put forward an ambitious MFF proposal. I was present to hear that speech and remember how much it impressed me at that time (the video of the speech is available here). This was not the first time that Gabriel had made this argument, but it seems with his departure Germany has reverted to a more traditional accounting perspective to the budget negotiations.

The Finland Presidency proposal

According to the Finland Presidency paper, the majority of Member State views on the overall level of the MFF differs between 1.00% and the Commission’s proposal of 1.11% (EU27 GNI). “In taking the negotiations forward, the Presidency sees that the overall level range is to be symmetrically narrowed from both ends”.

What this implies is that the Commission proposal for an MFF based on 1.11% EU27 GNI is seen as the high-water mark. No Member State is proposing to go beyond this ceiling, and many want to stay below it, with the Frugal Five presumably being the Member States advocating that the MFF should be limited to a ceiling of 1.00% EU27 GNI. In these discussions, the net payers tend to have the whip hand (as shown by the success of the UK in the last MFF negotiations in getting agreement on the political ceiling of 1.0% of EU28 GNI). One might surmise, therefore, that the ultimate compromise will be towards the lower end of this range.

The Presidency’s approach to allocating the budget between traditional and new priorities is based on the following principles:

1) Keeping the modernised division between the policy shares (approx. 1/3rd to Cohesion, 1/3rd to CAP and 1/3rd to other policy areas, excluding administration.

2) Balancing the proposed decrease between Cohesion and CAP, so that both policies would face a similar level of decrease compared to the current MFF.

3) Increasing funding for other policy areas, but limiting the level of increase proposed by the Commission.

Under the Commission proposal, the traditional spending areas of CAP and Cohesion would be reduced to 60% of the overall MFF. The Presidency proposal therefore implies some shift of the MFF budget back to agriculture and cohesion (with a combined share of 62.2%) . However, the overall budget ceiling is also reduced, so what this means for the absolute level of CAP and Cohesion spending remains to be determined. In any case, it is clear that the Presidency proposal implies the largest cuts fall on other policy priorities, both because the overall size of the budget is reduced and because their share of that budget is also reduced.

What does the Finland Presidency paper mean for the CAP budget?

As noted, the Presidency paper does not give specific figures to show how these principles would translate into actual budget numbers. But by making certain assumptions, the potential range of outcomes for CAP spending can be explored.

First, the Presidency proposes the principle that the range for the overall MFF level should be symmetrically narrowed from both ends. According to Euractiv reporting, the Presidency is proposing a range of between 1.03%-1.08% EU27 GNI compared to the range 1.00%-1.11% EU27 GNI supported in the bilateral discussions. This range does represent a symmetrical narrowing although these figures do not appear in its two-page discussion paper for the European Council summit itself. A similar range is used in an excellent post by Nicolas Wallace on the Science|Business blog on the Presidency budget proposal, although there are some minor divergences in my figures compared to those he presents.

Second, the Presidency paper is not specific in what it means by the MFF ceiling. There are three uncertainties: a) whether it refers to commitment or payment appropriations; b) whether it refers to an MFF total including the European Development Fund (EDF), as proposed by the Commission; c) whether it takes account of EU expenditure outside the MFF ceilings which has become an increasingly important element in the current MFF period (examples include the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund, the European Union Solidarity Fund, the European Investment Stabilisation Function, the European Peace Facility and the Facility for Refugees in Turkey).

For the purpose of the indicative calculations below, I have assumed that the Presidency principles a) apply to commitment appropriations; b) include the EDF in the ‘other priorities’; c) refer only to expenditure inside the MFF.

In parenthesis, the range identified by the Presidency of between 1.00% and 1.11% of EU27 GNI appears to conflate two well-known positions. The 1.11% figure is the Commission’s proposal for the overall MFF ceiling but this includes the EDF. The 1.0% figure is the current MFF ‘political ceiling’ but this refers to an MFF without the EDF. If the ‘Frugal Five’ want to be consistent, the corresponding GNI share including the EDF is 1.03%. In this context, calling for a 1.0% ceiling for an MFF including the EDF represents a further tightening of the ceiling compared to the current programming period. The 1.03% ceiling used for the lower bound in my calculations actually corresponds to maintaining the 1.0% ‘political ceiling’ from the current MFF.

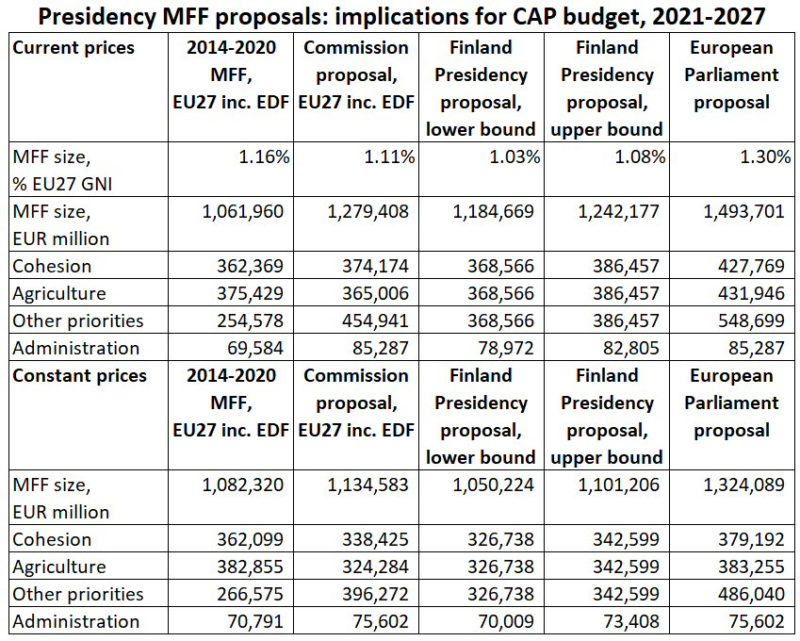

On the basis of these assumptions plus others set out in notes to the table, indicative spending levels for the CAP are shown in the following table in both current and constant prices. The conclusion is that, with the overall MFF pegged at the lower GNI percentage of 1.03%, the budget for the CAP is broadly maintained in current prices compared to the Commission proposal because it gets a higher share of this budget despite the reduction in the MFF size (in fact, a small increase is shown but given the inherent uncertainty in the way the calculations are done, I would not put too much weight on this).

If the MFF size is towards the upper end of the anticipated range, then the CAP budget increases in current prices relative to the Commission proposal by up to 6%. Conversely, if the overall MFF ceiling were to fall below 1.03% of GNI, then CAP expenditure would be cut relative to the Commission proposal.

In real terms (constant prices), the Presidency proposal would still represent a significant cut in the amount of CAP expenditure in the 2021-2027 period compared to the current MFF. With an MFF ceiling of 1.03%, the value of CAP expenditure in real terms is very similar to what is proposed in the Commission’s draft MFF proposal. The closer the MFF ceiling moves to 1.08%, the larger the amount available for CAP spending becomes.

Source: Alan Matthews calculations based on MFF figures in European Parliament’s MFF Resolution adopted 14 November 2018

Conclusions

The Finland Presidency discussion paper represents a first attempt to try to arrive at a landing ground on the size and composition of the next MFF. The Presidency has been asked by the European Council to submit a Negotiating Box with figures ahead of the European Council meeting in December. That leaves the Finns with about six weeks to narrow the range from that implied in this discussion paper! To arrive at a single figure within this short timescale would seem impossible, so one assumes that the best that can be hoped for in December is a narrower range.

What we learn from the exercise so far is that the Commission proposal for the overall MFF level has already been dismissed as too high. The question is whether the numbers converge to the mid-point of 1.055% or whether the net payers pull the ultimate landing point closer to the lower bound of the range identified in the Presidency discussion paper. Recall that a ceiling of 1.03% of GNI actually corresponds to the ‘political ceiling’ of 1.00% in the current MFF due to the inclusion of the EDF in the MFF figures.

It appears that even with a smaller MFF than that proposed by the Commission, the rebalancing proposed by the Finnish Presidency between the traditional and new spending priorities would at least maintain the level of CAP spending proposed by the Commission and could result in a small increase of between 0-6%. These are indicative figures at this point in time and can easily change as the negotiations proceed.

However, it is hard to see what might change the dynamics of this negotiation and bring the Commission’s ceiling level of 1.11% back into play.

In her Political Guidelines for the incoming Commission entitled “A Union that Strives for More”, the Commission President-elect von der Leyen included a number of additional spending commitments, including a new Just Transition Fund, a Sustainable Europe Investment Plan, a European Child Guarantee, tripling and not just doubling the ERASMUS+ budget and higher spending on external action investment. These commitments are not reflected in the Presidency’s discussion document and it remains an open question whether they will be in the Negotiating Box presented to the European Council next December. Many of these commitments will require legislative proposals to establish new instruments in order for their financing to be included in the next MFF. Even with further delays in agreeing the MFF it must be doubtful whether such legislation could be passed in time.

Another possible trigger that would change the dynamics of the negotiations, not entirely far-fetched, would be a referendum in the UK between Prime Minister Johnson’s Brexit deal and a Remain option in which the UK electorate votes to Remain. If the UK were to remain an EU Member State, it would alter dramatically both the political and economic context for the MFF negotiations.

Ultimately, the Parliament must also give its consent. The newly-elected Parliament passed a resolution setting out its views on the 2021-2027 MFF and own resources on 10 October 2019. The resolution confirms the Parliament’s position that the ceiling for the next MFF should be set at 1.30% of EU27 GNI and that spending on traditional EU policies such as agriculture and cohesion should be maintained in real terms. It also reaffirmed other elements in its negotiating position including reform of the own resources system and a rule of law mechanism where the ultimate European Council conclusions may disappoint. The Parliament declared “its readiness to reject any Council position that does not respect Parliament’s prerogatives or take due account of its positions”.

The Finns must now make a heroic effort to translate the principles set out in their discussion document for this October European Council into a Negotiating Box with figures for the December European Council. There will be another opportunity to take stock at that stage to see how far the negotiations have progressed.

This post was written by Alan Matthews