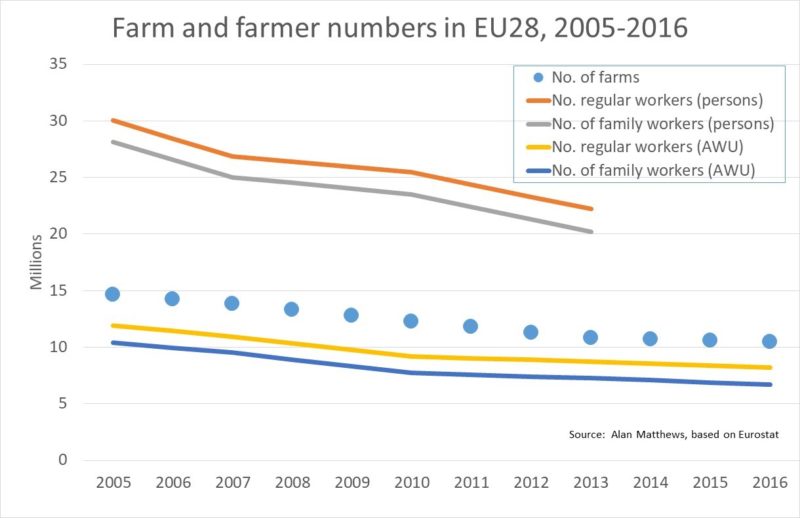

Commissioner-designate Wojciechowski highlighted what he called the “shocking information” on the decline in the number of European farms in his opening statement during his hearing in front of the AGRI Committee in the European Parliament earlier this week.

I presented the shocking information – shocking at least for some audiences – that during one decade, from 2005 to 2015, we lost four million farms in the European Union. The number of farms was almost 15 million, and after a decade there were fewer than 11 million farms. If we lose four million per decade, it is 400 000 per year. More than 30 000 per month. More than 1 000 per day. Our debate is scheduled to last three hours, which means that during this debate more than 100 European farmers will probably lose their farm and their job. For many of them it will be a tragic, shocking situation because it is not so easy to be a farmer today and then tomorrow to do something different – to be a taxi driver, for example. In many cases, this is a dramatic situation for European farmers.

Mr Wojciechowski did not propose specific ideas on how to slow down or reverse this trend but his statement implies that he would like to do so. This view is also shared in the amendment included by the previous AGRI Committee in its report on the Commission’s draft Strategic Plan Regulation which proposed to alter the first of the nine specific objectives of the CAP to read:

(a) ensure viable farm income and resilience of the agricultural sector across the Union to enhance long-term food security and agricultural diversity, while providing safe and high quality food at fair prices with the aim of reversing the decline in the number of farmers and ensuring the economic sustainability of agricultural production in the Union (bolding added).

Indeed, there has been a significant decline in both the number of farms and the size of the farm labour force in the EU as Mr Wojciechowski underlined (see next diagram). But for policy-makers to believe that this trend can be halted or reversed is simply nonsense.

The farm labour force decline is driven by differences in labour productivity between the farm and non-farm sectors. So long as these differences (adjusted for relative skill levels, differences in age distribution and differences in the cost-of-living in rural and urban areas) persist, young people will vote with their feet and move to higher-paying jobs. And farm consolidation (the converse of the out-migration of farm labour) is the principal way by which farmers can close the productivity gap with the non-farm sector. These basic structural dynamics are often ignored by those who look at farm policy with rose-tinted glasses.

The productivity gap between the farm and non-farm sectors

In a market economy, average living standards are determined by labour productivity (though the prevalence of rents as well as transfers can modify this relationship). Economic growth and rising living standards occur as workers move from lower-productivity to higher-productivity jobs. The main threat to farmers is not really cheaper imports under free trade agreements (which play a role), but advances in technology which raise the productivity of jobs in manufacturing and services sectors.

It is the competition from higher-paying jobs in these sectors that pulls labour out of farming. Economics students will recognise this statement as derived from the Harris-Todaro model developed in the 1970s and used in development economics to explain some of the issues around rural-urban migration.

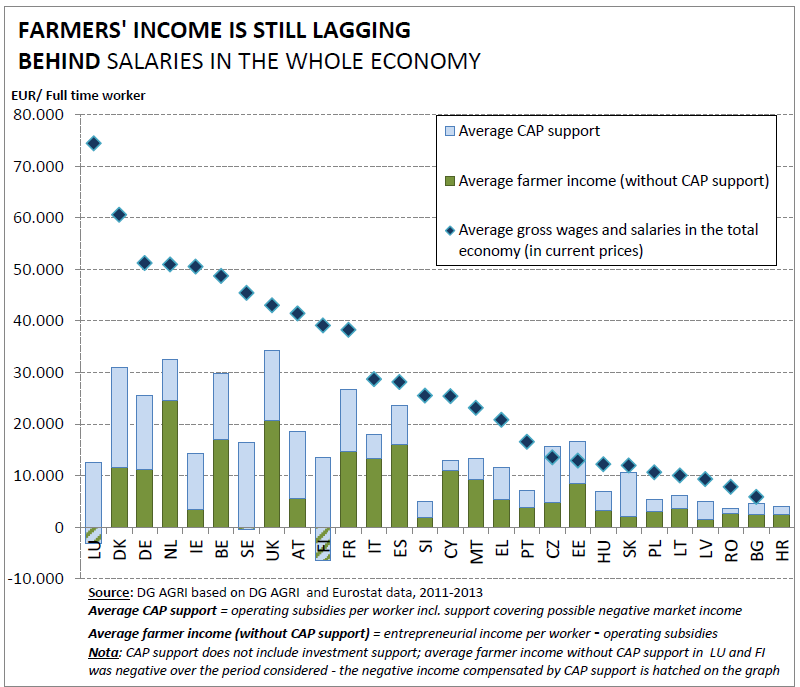

The inevitability of this process can be seen using a graph frequently used by DG AGRI to show that farmers’ incomes are lagging behind salaries in the whole economy. The graph below is taken from the Commission’s 2017 Communication The Future of Food and Farming which launched the post-2020 CAP proposals (there is another version in this DG AGRI brief on ensuring viable farm income).

Farm income in this graph is partitioned between market-related income and income from CAP support (the method used likely underestimates what market-related income would be in the absence of support because there would be a significant fall in certain input costs, notably land rents, if support were removed).

This graph cannot be taken to tell us anything about relative living standards in the two sectors because the comparison takes no account of the different sources of income that a household receives. However, the comparison does give us a good insight into the relative incentives to choose a farming versus a non-farming occupation. In particular, market-related income (which is better described as the value added by the family farm workforce) can be used to compare labour productivity in the farm and non-farm sectors. And it tells an unpalatable story.

In all countries the value added per family worker in agriculture is far lower than the value added per employee in the total economy (including agriculture). In one or two countries (e.g. Luxembourg and Finland) it is even negative.

CAP transfer payments help to make up some of the gap but in only a small handful of countries is average income from farming close to or above average employee income in the total economy. In general there are significant gaps, even with CAP support (note that support is calculated using the Eurostat agricultural accounts so CAP support includes national co-financing and other payments).

It is this productivity difference, even when mitigated by transfer payments through the CAP, that drives the out-migration from agriculture.

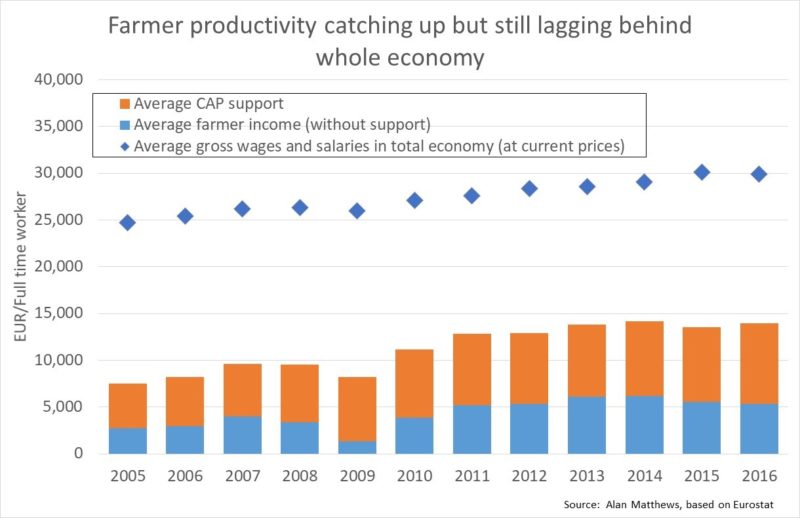

Farmer productivity is catching up

This productivity gap is closing over time. The next graph plots the same variables used in the DG AGRI graph for the EU28 since 2005 (the series ends in 2016 because this is the latest year for which Farm Structures Survey data are available).

During this period, gross wages and salaries per employee rose, in nominal terms, by 1.8% p.a. This was also the rate of inflation over the period, so it implies there was no real improvement in employee living standards in the EU. This is undoubtedly a contributory factor to the political fragmentation that we observe across the continent.

On the contrary, value added per family worker grew by a whopping 8.5% p.a. over the period. CAP support per family worker also grew by 5.1% p.a., so farmer income grew by 6.3% p.a., considerably faster than average wages and salaries.

This resulted in a narrowing of the percentage gap between average farmer income and average employee wages and salaries of 1.7 percentage points per annum, or by 19 percentage points over these eleven years.

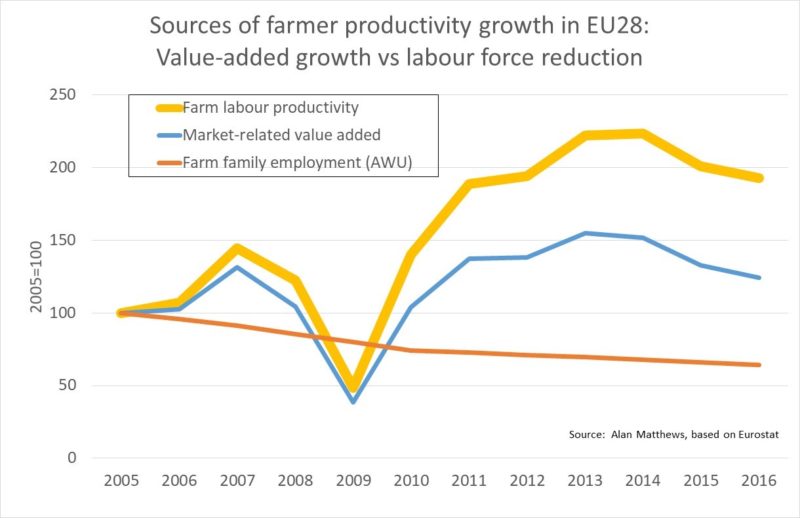

Partitioning labour productivity growth in agriculture

The problem is that around half of this impressive labour productivity growth in the agricultural sector has come from the drop in the number of farms and labour-saving technological change. The next diagram partitions agricultural productivity growth between growth in market value added and the reduction in the family farm labour force.

There is considerable volatility in the trend in farm labour productivity because of the market collapse at the time of the financial crisis in 2008-2009. However, concentrating on the end years, the overall doubling in the farm productivity index (from 100 to around 200) is accounted equally by an increase in market value added and a decrease in the family farm labour force. Specifically, the growth in farm productivity (8.5% p.a.) was due to a 4.2% p.a. increase in market value added and a 4.0% p.a. decrease in the family farm labour force, with the residual accounted for by interactions between the two. As shown in the very first graph above, the decline in the farm family labour force is very closely linked to the decline in the number of farms.

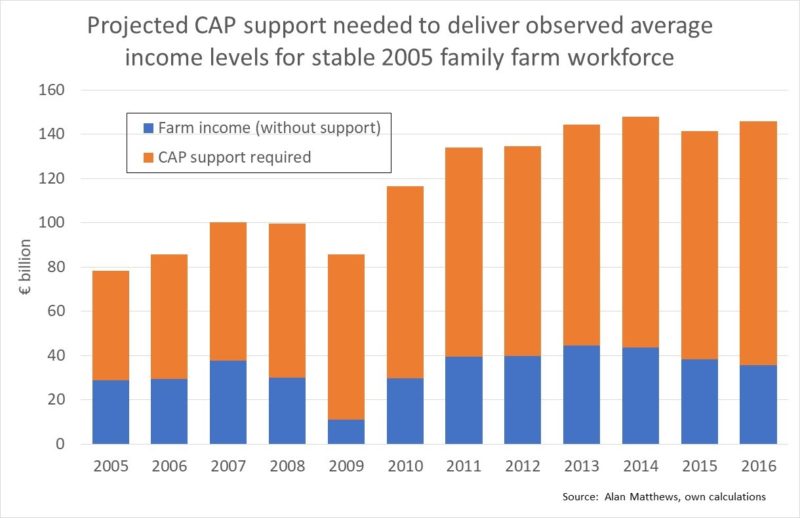

We can undertake a thought experiment to ask, by how much would CAP support have had to increase during this period to ensure the same increase in average farm income but maintaining the same level of family farm employment in 2016 as in 2005. The results are shown in the next figure.

Total CAP support in 2005 amounted to €50 billion and had increased to €58 billion in 2016. Under this hypothetical scenario where we want to maintain the same average farm income for a much larger labour force in 2016, CAP support would have had to increase to €104 billion. And this support would only increase year after year if no further reduction in the family farm labour force were to occur.

Conclusions

The evidence shows there has been some slowing in the rate of decline in the number of farms (the number decreased by 3.5% p.a. 2005-2010 but by 2.6% p.a. 2010-2016). This reflects the narrowing of the income gap between average farm incomes and average gross wages and salaries between these two periods. The Harris-Todaro model also emphasises the role played by the rate of unemployment in driving rates of rural-urban migration. Higher unemployment rates after the financial crisis may also have played a role in the slower rate of decline as unemployed families returned to subsistence holdings.

One question is whether policy can do anything to slow the rate of decline. One option would be to continually increase the level of CAP support to bring average farm income into line with average wages and salaries. I hope no one, even in COMAGRI, would support this idea. I have shown above that to achieve even the narrowing of the gap that occurred between 2005 and 2016 without loss of farms would have required an increase in the CAP budget (including national co-financing) of around a further €50 billion (on top of the existing €58 billion).

Furthermore, the evidence on whether CAP payments contribute to maintaining jobs in agriculture is very mixed and inconclusive (see Olper et al., 2014 for a review). Their study found that CAP subsidies did play a role in maintaining agricultural employment but the magnitude of the overall effect was not very high. Specifically, they calculated that the flow of out-farm migration prevented by the existing level of CAP support amounted to around 27,000 agricultural workers per year (compared to an average stock of 6.4 million workers in their study). This would imply a reduction in the annual rate of out-migration from 2.95% p.a. in the absence of the CAP to the observed 2.55% p.a. in the presence of CAP subsidies.

A more recent paper by Garrone et al (2019) also confirmed that CAP subsidies reduced the outflow of labour from agriculture (see here for the earlier non-paywalled working paper version). They estimated that an increase of 10% in the CAP budget would prevent an extra 16,000 people from leaving the EU agricultural sector each year but at a large budgetary cost. They concluded that the annual cost per job saved would amount to more than €300,000 (or around €25,000 per month). This would amount to far more than my back-of-the-envelope calculation above. As an employment policy, the CAP is simply terrible value for money.

A more effective role for policy would be to focus on increasing the market value added of those working in agriculture. One approach to increasing the market value added is to get consumers to pay more for their food. Giving producers greater powers to organise and set prices and strengthening their position in the food chain, or restricting competition from cheaper imports, would raise market value added though at the expense of consumers. Producing farm produce with higher quality attributes (pesticide free, animal welfare friendly, organic) can also attract a premium price from consumers, but the downside here is the additional costs involved to produce these quality foods.

I wrote a more extended discussion of how the CAP could support rural jobs in this Eurochoices Point de Vue (free to read). One of my arguments there was that measures to increase agricultural labour productivity will often accelerate the decline in the farm labour force but may lead to an increase in the number of non-farm jobs in rural areas.

There are other examples of policy trade-offs that are often overlooked. Some policy advocates call simultaneously for support for small farms as a way of maintaining agricultural employment (because they are more labour-intensive) while also opposing intensive farming and calling for more extensive farming. Unfortunately, these are incompatible goals though the advocates rarely recognise this.

The higher labour intensity on smaller farms means lower labour productivity which is exacerbated if farming is carried out more extensively. It is no surprise that the most successful small farms are those engaged in intensive enterprises with high value added per hectare such as vineyards or horticulture. Nor is it surprising that more extensive farming, such as organic farming, predominantly takes place on larger farmers in order to compensate for lower labour productivity. In 2017, the average size of utilised agricultural area of a non-organic holding was 16 hectares, while the average of a fully organic holding was 40 hectares. Of course, to debate this issue properly requires a precise definition of what is meant by extensive and intensive farming (is it use of chemical inputs, or knowledge more generally?) but value added per hectare together with labour intensity are the key determining variables.

If, as I argue, the large productivity gap evident in the previous graphs implies that farm numbers will continue to decline for some decades to come, the other role for policy is to facilitate and manage this process. For example, fewer farms implies farm consolidation, but not necessarily mega-farms, this is a policy choice (though for national governments rather than the EU).

The process of farm structural adjustment can also ‘trap’ low income farms in a poverty trap. Farmers who entered the industry many decades ago are not in a position to up sticks and find another job when their life experience has to do with looking after crops or animals. These farmers need and deserve income support until they come to retire from farming. This is far better given as a means-tested direct income support rather than support through the CAP which is linked to the area farmed. The Irish Farm Assist Scheme is an excellent exemplar of the approach that is needed (a somewhat dated audit review of the scheme also gives a good description). Ireland also administers a Rural Social Scheme which provides income support to underemployed farmers through participation for 19½ hours per week to provide certain services of benefit to rural communities.

The decline in the number of farmers is an inevitable part of economic growth. It reflects differences in productivity between the farm and non-farm sectors. As long as these differences (adjusted for age, skill and cost of living differentials) persist, out-migration of labour from the farm sector will continue. Neither Commission-designate Wojciechowski nor AGRI Committee amendments to the Strategic Plan Regulation can prevent this. It largely reflects the aspirations and choices young people make when choosing a career.

With all the attention on disappearing farms and family farm workers, I would like to conclude by quoting the final paragraph in my Eurochoices Point de Vue which highlighted the paradoxical evidence that, despite the drop in the number of farms, it is increasingly difficult to find farm workers even though there are jobs available.

While many observers regret the decline in the agricultural labour force, farmers themselves find it increasingly difficult to find people willing to work on farms. Little attention is given in farm policy discussions to improving the conditions of employment for farm workers, many of whom are increasingly migrant workers. While legislation in this area is a national responsibility, we should consider whether the CAP could not do more to encourage better apprentice arrangements, upskilling and career development, and, ultimately, higher wages for those who do much of the actual work of food production.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Photo credit: © Copyright Vieve Forward and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

Hi,

I am interested in biodiversity conservation and the “land sharing/land sparing” question – eg one form of the question could be: is it better to have extensive agricultural landscapes that are managed in a way that provides much space for wildlife (implying perhaps lower agricultural productivity because of set-aside conservation areas and devotion of some effort to managing farms for wildlife) or to have highly intensive (but sustainable) agriculture concentrated in areas of high agro-economic potential, meeting production needs and leaving unused large areas of the landscape which can return to a semi-natural state with enhanced biodiversity value? Does this trend in the number of European farms have any relation to the question – eg is the trend for farms to be consolidated into larger and more intensively managed units, meaning that there is probably less space for wildlife in these landscapes, or does the trend of decline in farm numbers represent the abandonment of small farms that will revert to “nature”? or both?!! The CAP is often criticised for its effect as a subsidy for habitat conversion and high-input farming and but if it is now being maintained at a level that is forcing inefficient small farmers off the land and this is providing a large area of land that can “re-wild” perhaps CAP could be said to be having , if inadvertently, a more positive impact on the fortunes of wildlife. ?

@Simon

This is a great question and I hope others will take the opportunity to respond because I am not really competent to address the broader issues of the land sharing/land sparing debate. However, I can make a few observations on the other parts of your comment.

My basic point is that the underlying forces shaping agricultural structures and farm numbers are structural in nature. These underlying trends can be modified but not reversed by policy and often with difficulty and at great expense. Although the evidence is mixed (because there are conflicting mechanisms at work), it seems more plausible that the CAP has maintained more small farms in existence than otherwise. My basic point contrasts with the position held by many critics of current agricultural trends that these are largely due to policy and the CAP in particular, as you note in your comment. This leads to the conclusion that changing the CAP can change these trends. This is the conclusion I challenge in this post.

It may be helpful to distinguish between land abandonment (land going out of managed agricultural production) and farm consolidation. Areas with unsuitable biophysical conditions are most likely at risk of abandonment and often these may be characterised by small farm structures, but which is the primary driver may be difficult to disentangle.

Finally, it is clear that without intervention more intensive agricultural production crowds out biodiversity and that this adverse trend is now reaching dangerous proportions. Regulatory interventions as well as financial incentives to address the way land is managed are therefore necessary.

Hello Alan

I am not sure that it is clear that without intervention more intensive agricultural production crowds out biodiversity, but no doubt you have some evidence/experience. The current trend in New Zealand is to set aside/protect land with lower fertility/excess slope or other production limiting aspects, in favour of using resource on land where there is a better return, i.e. instead of fertiliser all over, use it on the area where the response is greatest. This has meant that there are increasing areas on farms suitable for wildlife – increasing biodiversity.

Very informative

Alan Mathews’ clear exposition of the basic economics at work behind structural change should be compulsory reading for candidates to be any public servant with responsibility, direct or, tangential, for agriculture. Preferably there should be a test at the end to ensure they understand the material before they are let loose on actual decision-taking. It is frightening to reveal a major gap in knowledge as is implied by the statements by Commissioner-designate Wojciechowski.

Of course, the analysis could be taken further. In particular, structural change appears to lead to numerical growth among both the largest farms, whose size is associated with higher productivity and higher incomes, and the smallest that are operated on a pluriactive basis, where non-farm income provides sufficient resources to enable the household to continue to operate and live on the farm. The fastest declines in numbers are those in the middle, farms too small to reap advantages from size but too big to be operated part-time.

However, helping smaller farms to grow using public funds is no guarantee that they will assume the characteristics of the farms that are currently large; the existing cohort of smaller farmers may not have the management potential or may be limited by other barriers. The factors that have limited their ability to grow so far may be too strong.

While there is often broad support for interventions that attempt to raise productivity at the level of the individual farm, a case could be made that, from society’s viewpoint, it would be preferable to abandon such interventions and let market pressures in time drive out the unproductive units, only providing a short-term transitional agricultural support where the general social safety-net is incapable of coping with poverty. Of course, farm operators must be given sufficient time to adjust, but there is evidence that, as a group, they have in the past proved remarkably able to adapt in ways that protect their household incomes.

Dear Alan,

Thank you so much for this. Should indeed be required reading for policy-makers.

Dear Alan Matthews,

Have you heard something about the treadmill effect of the Farm Problem Theory, the mainstream ag economics in the US until 1990 ? One cannot explain low prices only by the decreasing cost and better productivity.

– Pesticides are labor-saving. More environmentally friendly agriculture needs more arms and brains, not less.

– European prices are dumping prices and not equilibrium prices because of the real nature of international prices, european agriculture is driven into a corner.

– Applying this reasoning to Africa, what could happen ? Oops, sorry that’s what we do yet !

– Better wages in other sector ? Or consequences of land market deregulations and capitalisation effects ?

Discussing it,

Best regards

Thanks for joining the discussion, Frederic. Let me reiterate my thesis that farm out-migration is driven primarily by differences in labour productivity in the farm and non-farm sectors and that, because of the major gaps in labour productivity that currently exist, a further fall in farm numbers can be expected.

Pesticides. Indeed, IPM methods are often more labour- intensive though they may be more profitable for some farmers if the extra costs are offset by lower expenditure on chemical pesticides, better quality produce or higher yields. If this is not the case, requiring more ‘arms’ implies lower labour productivity and reduces the survival prospects of the farm unless compensation is made available for the higher costs.

Dumping prices. I make the point in the blog post that higher market value added due to higher prices will tend to slow the rate of out-migration so on this we can agree. But even if international prices were to increase by, say, 20%, in response to moves to eliminate subsidies, this is a once-off effect while the contribution of labour outflow to increasing labour productivity is ongoing.

Capitalisation of payments. I agree and mention in the post that some share of direct payments intended to support farm income leak out to non-farmers, though I have doubts that this can be prevented by regulation of the land market.

Alan, Agriculture is one of the sector where productivity (in volume) has (and still) increased the more for decades. But prices go down and value go out the farms, so productivity (in value) is decreasing. Have a look on the “efficient but poor” hypothesis by T. Schultz the father of “human capital” and the only Nobel price that deeply works on ag economics !

It is always a usefull conceptual framework to balance views on structural issues.

Best regards,

Frederic

Hi Alan

That’s really interesting and clearly argued, thank you. Just a minor question: with respect to your first graphs demonstrating the difference between farming and non-farming incomes, I presume that you use mean incomes, and I was just curious to know what might happen if one were to consider median incomes.

Many thanks

@Kerry

Interesting question. Yes, the first graph is based on comparison of means in the two sectors. Income distributions are generally right-skewed with a long right tail, so the median income is lower than the mean income. This implies that median labour productivity in agriculture would be even lower than shown in the graph, but then so would median wages and salaries, so it is an empirical question whether the ratio of median productivities would be that different.

A more important caveat is likely to be that entrepreneurial income (the income accruing to family-owned factors from farming) also remunerates family-owned land and capital as well as labour. The comparisons made effectively assume that all of the value added in farming accrues to labour. If we assume capital and land should also be remunerated, then agricultural labour productivity is even lower than shown in the diagrams in the post.