EU policy on genetically-modified organisms (GMOs) for use in food and agriculture has been deadlocked for a number of years as member states, industry stakeholders and non-governmental organisations remain conflicted about the use of agricultural biotechnology. Three examples of the policy differences and contradictions that characterise this dossier include the following.

Indeed, France’s lower house of parliament (National Assembly) passed a law on 15 April prohibiting any GM plant that is approved at EU level from being grown, citing environmental concerns. The law follows a decree last month, which halted the planting of MON810 maize despite previous French bans being overturned by the French courts. The law now adopted by the National Assembly is similar to one rejected by the upper house (Senate) in February, which was seen as unconstitutional. The French ban on GM maize will now have to go to the Senate for approval. However, even if it is rejected again, the National Assembly will have the final say.

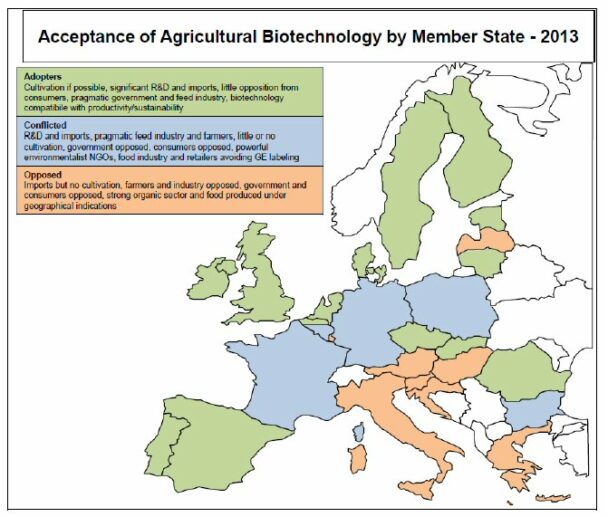

The USDA Foreign Agricultural Service characterises the position of EU member states into the following three groups (see also the map below showing Member State positions taken from this publication).

First, the “Adopters” include countries producing GE corn and MS who could be producers of GE crops, if the scope of crops approved for cultivation in the EU were wider and included crops with traits of interest for their farmers, industry, and/or consumers. Governments and industries in this group are generally pragmatic. Second, the “Conflicted” group includes countries where forces willing to adopt the technology (mainly the science community, farmers and the feed industry), are counterbalanced and usually out matched by forces rejecting it (consumers and governments, under the influence of active green parties and NGOs). Third, the “Opposed” group consists of MS where most stakeholders and policy makers reject the technology. Organic and products with geographical indications represent a significant part of food production in these countries. Market acceptance of animal biotechnology is low in the EU among policy makers, industry, and consumers, mainly due to ethical and animal welfare concerns.

The Commission’s 2010 ‘Cultivation package’ – coexistence

Given these divisions, in July 2010 the Commission proposed a package of two measures aiming to provide more possibilities for Member States to decide on GMO cultivation.

The first element of this package was the adoption on 10 July 2010 of a new Recommendation on guidelines for the development of national coexistence measures, replacing a previous Recommendation from 2003. The new Recommendation provides a more flexible interpretation of Article 26a of Directive 2001/18/EC (the Deliberate Release directive which governs the authorisation of GM plants for cultivation purposes) which allows Member States to adopt measures to avoid the unintended presence of GMOs in other crops. The new Recommendation recognises that the potential loss of income for producers of particular products, such as organic products, is not necessarily limited to the exceeding of the labelling threshold set at 0.9% in the EU legislation.

In certain cases, and depending on market demand and on the respective provisions of national legislation (e.g. some Member States have developed national standards of ‘GM-free’ labelling), the presence of traces of GMOs in particular food crops – even at a level below 0.9% – may cause economic harm to operators who would wish to market them as not containing GMOs. In those cases, Member States would be able to define measures going beyond the provisions of Directive 2001/18/EC, e.g. measures that aim to reach levels of GMO presence in other crops lower than 0.9%.

Some argue that Member States are constrained in deciding on isolation distances to ensure coexistence between GM and conventional crops because, as an exception to the requirement in the legislation that Member States must not prohibit, restrict or impeded the placing on the market of GMOs, they need to show that their measures are effective, necessary and proportionate to achieve the coexistence objective. However, for GM proponents the new Recommendation means that those Member States that do not wish to cultivate GM crops are, in practice, able to use the new guidance to impose isolation distances which would effectively preclude the possibility of GM crop cultivation.

The Commission’s 2010 ‘Cultivation package’ – the ‘opt-out’ clause

The second element of this package is a legislative proposal aiming to increase the possibility for Member States to restrict or prohibit the cultivation of authorised GMOs in their territory (the ‘opt-out’ proposal). The existing legislation allows Member States to use a safeguard clause to prevent cultivation, but safeguard measures must only be based on new or additional scientific evidence with regards to the health and environment safety of the GMO, and to date EFSA has found that no country can provide such evidence.

Thus the Commission proposal would allow Member States adopt measures restricting or prohibiting the cultivation of all or particular GMOs in all or part of their territory on the basis of grounds relating to the public interest other than those already addressed by the EU harmonised authorisation procedure. This proposal takes the form of the inclusion of a new Article 26b in Directive 2001/18/EC13 which would allow Member States to invoke grounds which are not related to the existence of adverse effects to health or environment to restrict or prohibit GMO cultivation.

The European Parliament adopted amendments to this proposal at first reading. The Parliament’s demands included new guidelines on GMO risk assessment which should not be based primarily on the principle of substantial equivalence or on the concept of a comparative safety assessment, and which should make it possible to clearly identify direct and indirect longterm effects, as well as scientific uncertainties. It wanted the long-term environmental effects of GM crops as well as their potential effects on non-target organisms to be rigorously assessed; the characteristics of the receiving environments and the geographical areas in which GM plants may be cultivated to be duly taken into account; and the potential environmental consequences brought about by changes in the use of herbicides linked to herbicide-tolerant GM crops to be assessed. It declared that no new GMO variety should be authorised until the risk assessment procedures were updated along these lines.

Concerning the new ‘opt-out’ clause, the Commission proposal was that Member States could restrict the cultivation of approved GMOs on their territory only on grounds relating to the public interest other than those already addressed by the harmonised set of EU rules which provide for procedures to take into account the risks that a GMO for cultivation may pose on health and the environment.

This was too limited for the Parliament, which proposed that Member States could justify restrictive measures based on grounds relating to environmental or other legitimate factors such as socio-economic impacts, which might arise from the deliberate release or the placing on the market of GMOs where those factors have not been addressed as part of the harmonised EU procedure, or in the event of persisting scientific uncertainty. Possible grounds were spelled out in detail, including environmental impacts which are complementary to the environmental impacts examined during the EU approval process, or grounds relating to risk management.

These scientifically-justified grounds may include:

– the prevention of the development of pesticide resistance amongst weeds and pests;

– the invasiveness or persistence of a GM variety, or the possibility of interbreeding with domestic cultivated or wild plants;

– the prevention of negative impacts on the local environment caused by changes in agricultural practices linked to the cultivation of GMOs;

– the maintenance and development of agricultural practices which offer a better potential to reconcile production with ecosystem sustainability;

– the maintenance of local biodiversity, including certain habitats and ecosystems, or certain types of natural and landscape features;

– the absence of adequate data or the existence of contradictory data or persisting scientific uncertainty concerning the potential negative impacts of the release of GMOs on the environment of a Member State or region, including on biodiversity;

In addition, the Parliament amendment would allow grounds relating to socio-economic impacts as the basis for cultivation restrictions by Member States. Those grounds may include:

– the impracticability or the high costs of coexistence measures or the impossibility of implementing coexistence measures due to specific geographical conditions such as small islands or mountain zones;

– the need to protect the diversity of agricultural production;

– the need to ensure seed purity;

Finally, other grounds may include land use, town and country planning, or other legitimate factors.

The Commission’s response to these amendments can be found here.

The Council position

Member States were unhappy with both the Commission proposal (feeling that the ‘public interest’ criterion to justify restrictive measures was too vague) and the Parliament’s amendment (believing that it threatened the integrity of the EU approval process). The Danish Presidency in March 2012 put forward an innovative proposal to try to break the deadlock. This allowed for two options:

– during the GMO authorisation procedure: upon request of a member state, the notifier/applicant has the possibility to adjust the geographical scope of the authorisation, thus excluding part or all of the territory of that member state from cultivation (ex ante intervention);

– after the authorisation procedure: the member state has the possibility to restrict or prohibit the cultivation of an authorised GMO, provided that the national measure does not conflict with the environmental risk assessment carried out at EU level (ex post intervention).

However, the Danes could not gather a qualified majority in favour of this proposal in 2012, with even some countries (such as France) who were using national restrictions opposing the opt-out.

This deadlock has continued until earlier this year when the Greek Presidency got the agreement of the Environment Council to re-open the discussion on the Commission’s opt-out proposal on the basis of a new Presidency compromise text. This incorporates those elements of the Parliament’s first reading amendments that the Commission has accepted. The change of heart was stimulated by the fact that the Commission was required to request approval of the Pioneer 1507 maize, following a ruling of the General Court of the European Union in September last year, given that it has already received six positive opinions from EFSA. In parallel, the Commission requested a fresh debate in the Council of Ministers on its opt-out proposal.

At the March Environment Council meeting, a large majority of Member States supported the compromise text, with both Germany and the UK indicating their position had changed compared to two years previously. Germany indicated it still needed to undertake further domestic consultations, but at the beginning of April its federal states voted to urge the national government to support the opt-out clause for individual EU states. The Greek Presidency now hopes to reach agreement on a Council first reading position before the summer.

Key changes in the Greek Presidency compromise proposal as compared to the Commission’s original proposal include the recognition that Member States can restrict or prohibit cultivation of an authorised GMO on grounds related to environmental policy objectives or other legitimate objectives such as land use, town and country planning, socio-economic impacts, and coexistence, provided that the arguments are distinct from those considered in the EU harmonised authorisation process.

In other words, a Member State should only use grounds related to environmental policy objectives which do not conflict with the assessment of risks to health and the environment which are assessed in the context of the authorisation procedures provided in the two above mentioned pieces of EU legislation, such as the maintenance of certain type of natural and landscape features, certain habitats and ecosystems as well as specific ecosystem functions and services.

Member States would also be able to base restrictions or a prohibition on GM cultivation on grounds of socio-economic impacts which might arise from coexistence concerns. These grounds could be related to the impracticability or the impossibility of implementing coexistence measures due to specific geographical conditions or the need to avoid GMO presence in other products such as specific or particular products or the need to protect the diversity of agricultural production or the need to ensure seed and plant propagating material purity.

A final change affects the ability of Member States to take ex ante and ex post interventions with respect to the EU harmonised authorisation process. Whereas the Commission proposal would have allowed Member States to opt for either ex ante or ex post interventions or both, the Greek Presidency proposal requires Member States to first seek to negotiate a voluntary opt-out with the GM applicant company. Only if the company refuses will the Member State be allowed to proceed ex post to adopt reasoned measures to restrict or prohibit that GMO once authorised on their territory.

GMO plans still face mix of criticisms

Negotiations continue in the Council working group on the compromise text, so further changes in the Council’s position could appear before the June Environment Council meeting. Not surprisingly, the Greek Presidency’s compromise proposal has attracted different reactions from different groups.

Biotech firms fear the opt-outs could undermine EFSA’s credibility, the integrity of the internal market and science-based decision-making. For environmental NGOs, the plans do not go far enough to allow countries to ban crops on environmental and health concerns not already assessed by EFSA. The rapporteur for the European Parliament’s amendments, the Liberal MEP Corinne Lepage, has been reported as saying that the Council also looks set to run into conflict with MEPs. She argues that the Greek Presidency compromise does not take into account any of the amendments proposed by the Parliament on the need to address the flaws of the EU authorisation system in the first place as well as the need to grant solid legal rights to ban GMOs to Member States, She predicts that if this text is adopted, it would trigger difficult negotiations with Parliament.

The Commission’s hope, in promoting the legislation, is that Member States would be more willing to base their decisions on the authorisation of new GM crops on the scientific evidence about their effects on health and the environment, knowing that they would now have greater autonomy to restrict or prohibit cultivation on their own territory if they so wished on other grounds including socio-economic grounds where coexistence measures (where Member States already have the ability to impose conditions which, de facto, make GM crop cultivation impractical) might not be effective.

The Commission’s hope is that this might then allow the authorisation process to work more expeditiously, and with less recourse to the Commission as the final arbiter. Whether the Member States would work the new legislation in this way remains unknown, of course, at this stage. In any event, the cultivation of GM crops within the EU looks set to remain more restricted than would be warranted by the lack of evidence of any adverse health or environmental effects of GM crop varieties released to date.

Ministers will hold a second round of talks at the Environment Council meeting on June 13, with the aim of an agreement before the summer.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit: Agriculture and Rural Convention