Last week the European Parliament’s Environment Committee (COMENVI) narrowly voted to adopt a report on the Commission’s proposal for a revised National Emissions Ceiling Directive (NECD). The NECD is one of the main measures designed to achieve the EU’s air quality targets in 2020 and 2030 under the Thematic Strategy on Air Pollution. The Commission’s proposal would tighten limits on emissions of sulphur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOC) and ammonia (NH3) that each member state could emit for the period from 2020 to 2030 as well as introducing limits for the first time on the amount of methane (CH4) emissions after 2030. As agriculture is the single largest source of both ammonia and methane, this directive could potentially have an important impact on the agricultural sector.

The COMENVI opinion will now go forward to the full Parliament plenary at its first reading of the Commission proposal probably in October. Interestingly, the COMENVI rapporteur, Julie Girling MEP, took the unusual step of voting against her own report. She views the strengthened targets in the amended opinion as unrealistic (particularly as regards ammonia), and argues that the new targets have not been robustly impact assessed.

Although the proposed emission limits on ammonia after 2020 will probably have the greater impact on agriculture, in this post I want to focus on the proposed inclusion of methane ceilings in the NECD. Environmental organisations, such as AirClim and the European Environment Bureau, have strongly supported the Commission’s proposal to include methane in the revised Directive. Farm organisations, supported by COMAGRI in the Parliament, have argued against methane limits. Member states in the Council are also opposed to methane limits, and the most recent Presidency draft of the Council common position (from April 2015) has removed them from the proposal. At its June 2015 meeting, most countries at the Environment Council of Ministers objected to the inclusion of methane limits, thus setting the scene for a clash between the two institutions.

In this post, I examine the arguments for and against including methane emission ceilings in the NECD as part of the EU’s air quality package. I conclude, along with COMENVI, that separate methane ceilings in the NECD are warranted. However, there is a case for reviewing the reduction commitments and for increasing the flexibilities around these levels, given that the main argument for including methane ceilings is to encourage international action on this issue.

Air pollution is a problem

Air pollution is a major public health concern. Poor air quality contributes to premature death, to sickness absences from work, significant healthcare costs, productivity loss, crop yield loss and damage to buildings. In Europe, the total external health-related costs to society from air pollution are estimated to be in the range of €330-940 billion per year. Last week, a widely-publicised French Senate report calculated that the cost of air pollution to France alone every year was over €100 billion.

In addition to the impacts on human health, air pollution also has several environmental impacts, affecting the quality of fresh water and soil, and the ecosystem services they support. For example, ground-level ozone damages agricultural crops, forests, and plants by reducing their growth rates. The cost of the crop yield loss has been estimated at around €3 billion for 2010. Eutrophication due to air pollution has also led to biodiversity loss.

While work has been done to reduce air pollution across the Union, many member states are falling short of agreed standards. Moreover, the EU remains far from its long-term objective; to adhere to the recommended pollutant limits in the WHO’s 2005 air quality guidelines.

Focus on ozone and methane

Particulate matter (PM) and ground-level ozone are Europe’s most problematic pollutants in terms of harm to human health. In terms of damage to ecosystems, the most harmful air pollutants are ozone, ammonia and nitrogen oxides. Methane is better known as a greenhouse gas but it can also be considered a pollutant because it acts as a precursor, or contributor, to the formation of ozone.

Ozone occurs naturally at ground-level in low concentrations which are not considered a threat to the health of humans or the environment. Ground-level ozone is also called tropospheric ozone because it is found in the lowest region of the atmosphere extending from the earth’s surface up to a height of about 6-10 km which is the lower boundary of the stratosphere. Ozone in the stratosphere (stratospheric ozone) is vital for life because it absorbs most of the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. But at ground-level ozone has become an increasing problem and this is what we think of as ‘bad’ ozone.

In the troposphere, ozone damages crops and forests and injures or destroys living tissue. Smog due to ozone causes respiratory problems, worsens heart disease, bronchitis, and emphysema, and brings about premature death. Tropospheric ozone is also a significant greenhouse gas, and is the third most important contributor to greenhouse radiative forcing after CO2 and CH4.

Although the most important cause of premature death due to air pollution is attributable to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations, ozone is also directly implicated as a component of smog. According to the European Environment Agency’s (EEA) air quality report for 2014, PM2.5 was responsible for around 430,000 premature deaths in the EU-28 in 2011, originating from long-term exposure. The estimated impact of exposure to ozone concentrations in 2011 was about 16,160 premature deaths per year in the EU-28, originating from short-term exposure.

In addition, ozone is considered to be the most damaging air pollutant to vegetation, adversely affecting vegetation growth and crop yields, reducing plants’ uptake of carbon dioxide and resulting in serious damage and an increased economic burden for Europe. In 2011, about 18% of the agricultural area in the 33 EEA member countries was exposed to ozone levels above the target value for protecting crops, with the highest impacts felt in Italy and Spain. The long-term objective was exceeded in 87% of the agricultural area. In addition, the critical level for the protection of forests was exceeded in 67% of the total forest area in the EEA-33, and in 84 % of the EU Natura 2000 areas in 2011.

Unlike some other air pollutants which are directly emitted to the atmosphere, e g. from vehicle exhausts or chimneys, ozone is not directly emitted from any one source. Tropospheric ozone is formed by the interaction of sunlight, particularly ultraviolet light, with hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides, which are emitted by automobiles, gasoline vapours, fossil fuel power plants, refineries, and also agriculture. It is thus an example of a secondary air pollutant which is formed in the atmosphere from so-called precursor gases.

Methane is just one of the ozone precursors and plays a different role to other precursors such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from transportation, solvent use, industrial processes and gasoline evaporation. It is relatively long-lived in the atmosphere (around 12 years) and therefore leads to ozone formation on a regional/ hemispheric/global scale, contributing to the ‘background’ level of ozone formation upon which episodes formed by more reactive VOCs are superimposed. Once ozone has been produced it may persist for several days. In consequence, ozone measured at a particular location may have arisen from VOC and NOx emissions many hundreds or even thousands of kilometres away.

These background ozone levels have increased by about a factor of three over the last 50 years in the northern hemisphere and are currently close to levels that damage human health and the environment (mainly vegetation). Ozone levels in the future will be governed largely by changes in methane and nitrogen oxides NOx ; according to a recent scientific paper, methane induces an increase in tropospheric ozone that is approximately one-third of that caused by NOx. Control of methane and NOx emissions on a hemispheric scale would thus reduce the formation of ozone considerably.

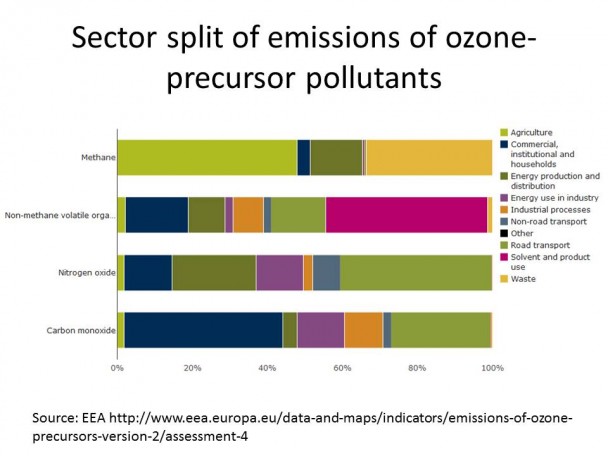

According to the latest EEA assessment, emissions of the main ground-level ozone precursor pollutants have decreased across the EEA-33 region between 1990 and 2011; nitrogen oxides by 44%, non-methane volatile organic compounds by 57%, carbon monoxide by 61%, and methane by 29%. This decrease was achieved mainly as a result of the introduction of catalytic converters for vehicles, which significantly reduced emissions of nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide from the road transport sector, the main source of ozone precursor emissions. Despite this progress, recommended ozone levels are often exceeded.

Ozone levels typically become particularly high in regions where considerable emissions of these precursor gases combine with stagnant meteorological conditions, high levels of solar radiation and high temperatures during the summer. Ozone is regulated under the 2008 Air Quality Directive which sets non-binding thresholds for ozone concentrations.

Concentrations of ground-level ozone significantly exceeded these standards during summer 2014, according to the EEA’s latest analysis. However, the number of exceedances was lower than in many previous years, in line with the long-term downward trend observed over the last 25 years. A report last year by ECORYS discusses in detail the reasons for non-compliance with ozone target values. It highlights the influence of hemispheric background ozone and the transboundary nature of ozone and its precursors. In short, reducing ozone levels in Europe requires international action to reduce levels of background ozone, and full mitigation may be beyond the control of member states alone.

EU air quality policy framework

European air policy has made progress in past decades in reducing air pollution. The air is cleaner today than two decades ago. However, despite improvements, substantial impacts remain: Europe is still far from achieving its long-term goal to attain ‘levels of air quality that do not give rise to significant negative impacts on, and risks to human health and the environment’.

In 2005 the EU launched its Thematic Strategy on Air Pollution to achieve improvements in 2020 relative to the situation in 2000, with concrete objectives concerning impacts on human health and the environment. EU air pollution legislation follows a twin-track approach of implementing both air quality standards and emission mitigation controls. Air quality standards are set out in the ambient air quality directive which was revised in 2008. Emissions of pollutants to air, including precursors to key air pollutants such as ozone and particulate matter, are controlled under the 2001 National Emissions Ceiling Directive (NECD). There is also EU-wide legislation on some source-specific emissions such as the industrial emissions directive, the directive on large combustion plants, directives on petrol storage and distribution, etc.

The Commission commenced a review of its air quality policy in 2011. In December 2013, it published its European Clean Air Package, backed by a substantial impact assessment. The package outlines measures to ensure that existing targets are met in the short-term and sets new air quality objectives for the period up to 2030. It consists of four elements: a Clean Air Programme for Europe; a proposal for a Decision to ratify the 2012 amendment to the Gothenburg Protocol to the UNECC Convention on Long Range Trans-boundary Air Pollution on behalf of the EU; a proposal for a new Directive to reduce pollution from medium-sized combustion installations, such as energy plants for large buildings, and small industry installations; and lastly, the legislative proposal revising the 2001 NECD on which the Council and Parliament look set to disagree.

The 2013 Commission proposal to revise the NECD

The 2013 Commission proposal revising the NEC Directive repeals and replaces the current Union regime on the annual capping of national emissions of air pollutants so as to integrate the EU’s international commitments for 2020 under the 2012 amendment to the Gothenburg Protocol. The current targets in the 2001 NECD for national emissions of sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, non-methane volatile organic compounds and ammonia are maintained until 2020 and a new 2020 ceiling for PM2.5 is added.

The controversial elements concern the new targets for 2030. New reduction commitments for all of those pollutants and for particulate matter (PM2.5) are set for the period from 2030 to deliver further reductions in background pollution to enable levels of air quality that are closer to those recommended by the WHO. The proposal also sets out reduction commitments for methane for the period starting from 2030.

The 2030 targets under the Commission’s proposal could begin to bite earlier. The proposal defines intermediate emission targets for the same pollutants for 2025 determined by a linear reduction trajectory established between their emission levels for 2020 and the emission levels defined by the emission reduction commitments for 2030. Member States are required to take all the necessary measures, unless they entail disproportionate costs, to keep their 2025 anthropogenic emissions of all the pollutants, including methane, within these ceilings. However, the 2025 ceilings are non-binding and take the nature of ‘best endeavour’ commitments. In the COMENVI report, intermediate targets for methane in 2025 were removed.

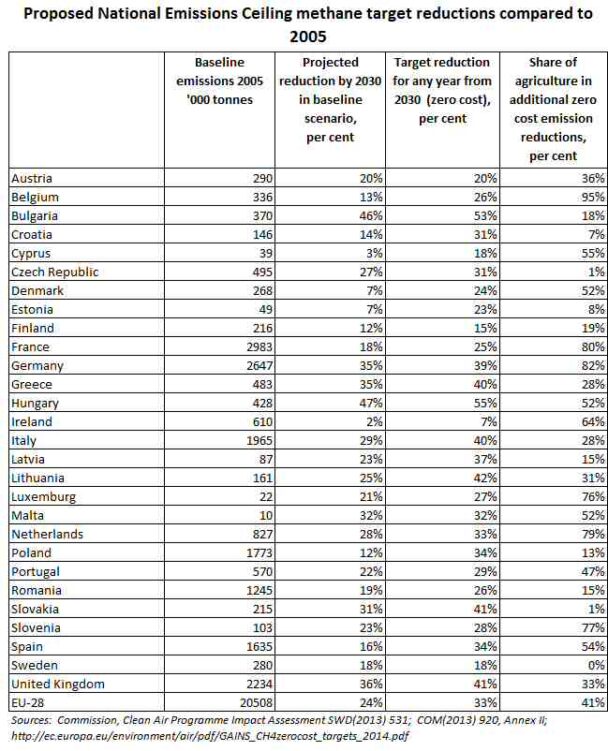

Another reason for the controversy around the 2030 targets is that they are allocated as national ceilings by member state for each pollutant. The Commission has established the limits for individual member states based on where it has assessed the most cost-effective measures can be taken. The Commission uses the Greenhouse Gas and Air Pollution Interactions and Synergies (GAINS) model for this purpose. This is an integrated assessment model developed by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) for the purpose of describing policy-relevant pathways of atmospheric pollution from anthropogenic sources. The resulting reduction commitments for methane which are set out in the draft proposal are shown in the following table.

The approach taken in setting these targets is set out in the Impact Assessment of the Commission’s Communication on a Clean Air Programme for Europe (Annex 10). The baseline reference projections assume that existing measures will lead to a reduction in methane emissions in any case by 24% in the EU-28 by 2030. This baseline reference is the same as that used for the EU’s Climate and Energy Package agreed in 2014, and assumes that the EU’s renewable energy targets as well as climate targets will be met. The reductions are due to lower methane emissions from waste treatment (driven by EU legislation on solid waste disposal and waste water management) as well as from the energy sector (due to improved gas distribution networks as well as reduced use and production of coal and gas). In contrast, methane emissions from the agricultural sector are expected to fall only by 2% in the reference scenario.

There are large differences between member states in the baseline scenario, ranging from a 46% reduction in Bulgaria to a 2% reduction in Ireland. Larger reductions are expected in the new member states and smaller reductions in the old member states because the latter have already implemented much of the waste management legislation and emissions from agriculture are a larger share of their total emissions.

Based on estimates by the IIASA model, a further 8 percentage point reduction could be delivered at zero cost with measures that are either cost neutral or pay for themselves through energy recovery, bringing the 2030 emission reductions at EU level to 33% compared to 2005 based on a conservative assumption of using only currently available technologies. The last column in the table above shows the expected contribution of zero cost measures in agriculture in contributing to this extra effort.

The further emission reductions expected from agriculture come largely from anaerobic digesters installed on large pig units as well as on some dairy and cattle farms in some countries, a ban on agricultural waste burning, and the use of intermittent aeration and alternative hybrids on rice farms.

Overall, for the EU-28, around 41% of the additional zero cost measures for methane reduction are found in agriculture, which coincidentally is the same as agriculture’s share in total methane emissions (see diagram below). However, the role of reductions in agricultural emissions is expected to vary greatly across countries. In some countries, such as Sweden, Slovakia, Czech Republic and Croatia, agriculture hardly features, but in others, such as Belgium, France and Germany, the great bulk of their additional effort will take place in agriculture.

The arguments for methane limits

The first mention of including methane limits in air quality legislation goes back to 2005 when the impact assessment for the Commission’s Thematic Strategy on Air Pollution (though not the Strategy itself) noted that control of methane and NOx emissions on a hemispheric scale would reduce the formation of ozone considerably. In that year, the consulting company ENTEC UK was commissioned to undertake work in support of a review of the emissions targets in the 2001 NECD. As part of this work, it was asked to consider the feasibility of an emission ceiling for methane.

The ENTEC report concluded that “an emission ceiling could provide ‘added value’, if implemented with the primary objective of reducing hemispheric background concentrations of tropospheric ozone”. This was based on the view that “The inclusion of methane within the NEC Directive would focus Member State attention on methane and could therefore be a means by which Europe can move towards the maximum technically feasible reduction (MTFR) scenario”. It noted that “further investigations will be required … to understand the implications of modelling methane within the integrated assessment modelling framework, in order to establish cost-effective emission ceilings”.

The report also emphasised that “a decision for the inclusion of methane within the NECD should be made on the basis of further research, to understand the absolute and relative significance of European methane emissions to ozone formation.” In its view, the relatively small contribution made by member states to the total global emissions of methane, coupled with the projected reductions under climate change policies, underlined that a global response was required.

In putting forward methane limits in the Clean Air Package, the Commission advanced two arguments. First, methane limits would provide direct climate co-benefits whilst also preparing the ground for international action. Second, a methane ceiling would exploit the substantial potential for low- or zero-cost reduction, thus complementing the VOC and NOx reductions required to reduce the concentrations of ozone both in the EU and internationally.

The first argument puts emphasis less on the direct benefits in terms of ozone reduction for the EU and more on the impetus it might give for international action. This reflects the nature of methane as an ozone precursor that its consequences are long-range and trans-boundary. As the impact assessment summarises: “Such targets would have a small but significant effect on ozone concentrations across the northern hemisphere, but more importantly could provide a negotiating platform to pursue comparable methane emission reductions internationally”.

Or, as the Commission methane non-paper circulated to member states in 2014 states:

The objective of the methane NERC is to provide a first step towards international work on methane emission reductions…. A specific commitment for the EU and its MSs on methane emissions would be a stepping stone for the EU to address global methane emissions and hence background ozone levels as well as short-lived climate pollutants at the international level.

The second argument can be summarised by saying that, given there are lots of opportunities to reduce methane either at no cost or even at ‘negative’ cost (that is, by adopting measures where the benefits of methane recovery outweigh the cost), then why not do it? We noted above that the 2030 ceilings by member state were derived using the GAINS model on the basis that the required reductions in methane emissions could be implemented by measures which, while requiring up-front investment, would have a positive return.

This argument was further elaborated in the Commission’s 2014 non-paper on methane emissions:

The tabled NERCs include only measures that are at zero or negative costs assuming a commercial discount rate on revenue of 10%. The principal measures are farm scale anaerobic digestion (mainly pig farms), anaerobic digestion of waste in the food industry, improved biogas recovery from solid waste and wastewater plants, improved control of gas leaks in gas distribution and gas recovery during oil and coal production. The overall effects of implementing these measures are cost saving in the range of €2.4 to 4 billion, depending on the level of technological progress up to 2030.

Criticisms of including methane ceilings

Opponents of including methane ceilings in the revised NECD also make two arguments. The first is that the specific targets included in the draft directive are not cost-effective. In other words, they simply don’t believe the GAINS model and its promise of costless reductions. For those interested, DG ENVI has made available the marginal abatement cost curves for methane emissions that result from the GAINS model for each member state showing the amount of emissions that can be reduced at zero cost. I used these estimates to calculate the share of agricultural reductions in the total in the table above.

The second is the danger of ‘over-regulation’. Here the argument is made that, because methane is a greenhouse gas and is thus already controlled by the national emissions ceilings in the Effort Sharing Decision (ESD), there is no need for a separate methane target in the air quality legislation. As COPA-COGECA put it in its position paper on the proposed NECD revisions (the same argument has also been made by the COMAGRI rapporteur on the legislation and by the UK government):

Copa-Cogeca recognises that there are some environmental effects of methane as it affects the formation of ground-level ozone. However, methane remains predominantly a GHG gas and hence part of the EU Effort Sharing Decision. Therefore, methane should be regulated by EU climate policy and be excluded from the NEC directive. Otherwise, it would limit the flexibility offered in the Effort Sharing Decision to meet GHG reduction targets.

The Commission responses to this second criticism in its methane non-paper were not convincing. It argued that, although methane is a part of the Kyoto basket of gases, there was no significant risk of double regulation or limitation on future climate change policy. In support of this argument, it made two procedural points. First, it noted that the current Effort Sharing Decision aims at 2020 and that there is currently no legislation in force/proposed for 2030, thus opening for separate methane reductions for 2030. While factually correct, this is a rather devious argument given that the Commission has announced that it will bring forward such legislation in 2016.

Its second point was that any future climate policy is likely to go significantly beyond the current ESD, in practice also entailing methane reductions beyond the zero cost measures proposed in the NECD. Thus, it argued that the setting of methane ceilings now will therefore be an important stepping stone also for climate change action, including for short-lived climate pollutants. Again, as the methane targets in the draft NECD do not come formally into force before 2030 (albeit member states should also strive to meet a 2025 target provided it does not entail disproportionate costs) while the ESD greenhouse gas emission ceilings will apply from 2020, neither is this argument likely to convince many waverers.

The case for retaining methane ceilings

However, there is a perfectly good argument that the Commission could have made to retain a separate methane ceiling in the air quality legislation. Not all greenhouse gases controlled under the ESD play the same role as an ozone precursor. We have two separate objectives, and to meet these objectives requires two separate instruments.

The argument that setting national ceilings for methane may limit the flexibility offered in the ESD to meet the Union’s greenhouse gas reduction targets does not hold water. Provided that the separate methane ceilings are determined by the relative costs and benefits that reducing methane would have in lowering ozone levels, it is justified to implement these ceilings on their own terms. Climate change policy can then be determined on the basis that the air quality legislation is already in place.

Put another way, the ESD directive does not specify which greenhouse gases a country should reduce. It could, in theory, focus all its attention on reducing carbon dioxide, but leave methane emissions untouched. Separate methane ceilings in the NECD would ensure this does not happen.

A more sophisticated objection to the Commission’s proposal is that, if the Commission calculations and the GAINS model are correct, there is no need to fear that this would happen. Why would a country forego the opportunities to meet its ESD targets by reducing methane emissions at zero or negative cost? Hence, according to those wishing to scrap the separate methane ceilings in the NECD, they are redundant under the Commission’s own analysis that methane reductions represent ‘low-hanging fruit’ that can be reduced at zero cost.

However, as we have seen, there is debate over whether methane emissions can be reduced at zero cost. Further, it is justified to reduce methane emissions even when this is costly provided that the benefits to health and environment exceed these costs. Finally, those arguing for scrapping the methane ceiling give no weight to the Commission’s main argument that it is necessary in order to galvanise international action to reduce emissions of this ozone precursor.

This argument was accepted by the COMENVI’s rapporteur for the NECD dossier, Julie Girling, in her draft report:

There are important interactions between climate and air quality policies. With this in mind, your rapporteur has chosen to maintain methane within the scope of this Directive. Methane emissions are already regulated directly under existing EU legislation, for example under the Landfill of Waste Directive, and indirectly through the Effort Sharing Decision, as it is a powerful greenhouse gas. However, methane is also a significant ozone precursor and it is therefore important to tackle it specifically in this legislation.

Of course, because the two policies are jointly implemented, there is an interaction between them. The impact assessment of the Clean Air Programme notes that its analysis confirms that a more ambitious climate policy could make reaching the new air quality objectives cheaper by removing highly polluting sources such as coal plants or reducing fuel consumption. But that does not necessarily justify more stringent methane targets, because the likely benefits of further methane reductions will also be reduced.

Are the proposed methane ceilings right?

While the principle of separate methane ceilings can be easily justified, it is a separate question whether the Commission’s proposed national ceilings based on the GAINS model make sense or not. The modellers themselves and the Commission have noted the large margin of uncertainty around their figures. As the impact assessment for the Clean Air Programme noted: “… uncertainties in the projections are substantial (covering e.g. the impact of abolishing milk quotas), and may significantly change national methane emissions and the affordability of possible emission reduction targets”.

Following complaints from member states about the reliability of the GAINS model projections, revised scenarios for the reduction of emissions were presented to member states by the Commission in January 2015. While these revised figures for pollutants other than methane appear in the most recent version of the Presidency’s compromise text from April 2015, there are no new methane figures as the Presidency instead proposed to delete the methane ceilings altogether. Thus, we do not know whether the Commission proposed changes to the methane reduction commitments set out in the 2013 NECD proposal and, if so, what they might be.

The existence of negative-cost or even zero-cost measures to reduce methane begs the question why these measures have not already been implemented. It may be that there are social, institutional or financial constraints to adoption which cannot be represented in the GAINS model. If this were the case, then remaining within the methane ceilings could imply additional costs for national economies, including agriculture.

In this connection, COMENVI made the suggestion in its adopted report that the CAP, at its mid-term review in 2017, should be amended to include Air Quality as a “public good” with particular reference to ammonia or methane, or both, so as to offer Member States and relevant regional and local authorities there under the opportunity to contribute to emission reductions with specific measures, and for assistance to do so.

The fact that measures to improve human health or the environment might have a direct economic cost in terms of lower GDP (but higher welfare) is not, in itself, a decisive argument not to proceed. The proper metric is whether the additional health and environmental benefits are sufficient to justify these costs. While there may be uncertainty around the costs of methane reductions to meet proposed 2030 ceilings, it is also necessary to look at the potential benefits.

The health and environmental benefits of reduced tropospheric ozone were enumerated earlier. But the nature of background ozone as a hemispheric or global problem also plays a role.

Measures taken by the EU alone to reduce methane as an ozone precursor will have a limited impact on ozone levels over Europe unless similar steps are taken internationally. Hence the Commission’s justification to introduce methane NERCs to provide a first step towards international work on methane emission reductions.

But, it must be admitted, the subsequent steps to reaching such an international agreement are not clearly spelled out. The Commission has not laid out a strategy how it intends to achieve this goal. Given this void, there is a case for reviewing the reduction commitments and for increasing the flexibilities around these levels, given that the main argument for including methane ceilings is to encourage international action on this issue. As the ECORYS report notes: “Evidence from literature and discovered during this study also indicates that ozone target values and long-term objectives are not technically attainable without disproportionate cost at the Member State level due both to the transboundary nature of the ozone pollution and the increasing global background concentrations.”

To be crystal clear, this conclusion only relates to the methane ceilings in the proposed NECD. I leave discussion of the ammonia ceilings to another post.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit: Alberto Hernández/Flickr used under a Creative Commons licence

Dear Mr Mathews,

thank you for your article. I do believe that an important part of the answer to the logic question about the reason there has not been implemented the admittedly ‘low or negative cost’ reduction of methane is that agriculture is not like other economic sectors.

If you look at the report from the JRC, which uses the same database GAINS and the same model with the Commission’s Impact Assesment ‘an Economic Assessement of GHG Mitigation Policy Options for EU Agriculture’ EcAMPA, you will see that a methane reduction would entail huge structural changes that come at prohibitive costs. In addition, the report goes on, argueing that if we reduce production here in Europe where we have those high environmental standards, then we would simply increase the production elsewhere in places with much less efficient production and lax environemental regimes and by doing that we would risk offseting any positive effect.

You can find the report here. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/default/files/jrc90788_ecampa_final.pdf

Thank you

Best wishes,

Evangelos

@ Evangelos

Thank you for this response and for drawing attention to this JRC report. It does indeed provide relevant information although there are important differences between the scenarios examined in that report and the scenarios examined for the purposes of the NECD emissions ceilings. Thus, there is no contradiction between the significant mitigation costs for non-CO2 emissions from agriculture identified in the JRC report and the potential for zero-cost mitigation in the NECD impact assessment.

Both studies, as far as I can judge, use the same reference scenario for the growth in methane emissions to 2030. The reference scenario is based on projections for livestock numbers and other agricultural activity, and only assumes methane mitigation on a voluntary basis where it is profitable for the farmer to undertake it. In addition, as you point out, both reports use the same underlying mitigation technologies and their associated cost structures as included in the GAINS model database.

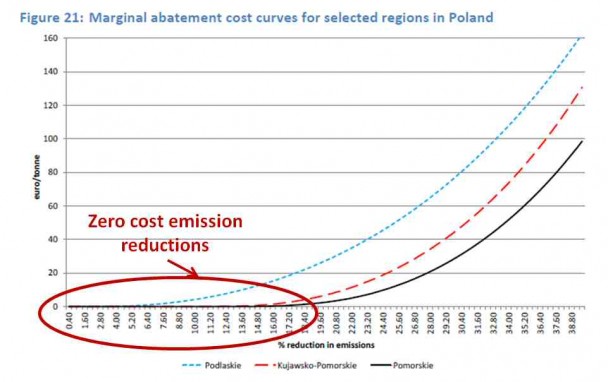

On this basis, the JRC report calculates marginal abatement cost (MAC) curves for each EU NUTS2 region for reductions in GHG emissions (which includes both nitrous oxide as well as methane) ranging between 0 and 40% in 100-step intervals, relative to the reference scenario levels in 2030. Some example MAC curves are given in the report, and I reproduce the one for some Polish regions below. Note the potential (depending on the region) for zero cost emission reductions in all regions of between 5% and 17%.

The difference between the two reports relates mainly to the scale of the emission reductions sought to be achieved from the agricultural sector (another difference is that the JRC report also takes nitrous oxide emissions and measures for their abatement into account, but it is the scale issue which is crucial). The JRC scenarios assumed that the objective was to meet a climate change target which would require non-CO2e emission reductions of either -19% or -28%, respectively. It estimates that, because the contribution from changes in livestock management and production technology would be rather limited by 2030, this would require a substantial contraction of the beef herd. Note that it also concludes that farm income would be higher in this scenario because imports would not fully compensate for the lower production and beef prices would be substantially higher !

However, the NECD impact assessment specifically only takes into account the zero-cost options which are covered by the eclipse in the diagram above. Its estimate of the reduction in agricultural emissions is thus not based on meeting some exogenous target, as is the case with the JRC report. Rather, it derives its estimate by looking solely at the quantitative contribution of the zero-cost options for methane reduction in the agricultural sector. It thus arrives at much lower targets for methane reductions than used in the JRC report.

As I pointed out in the post, the NECD impact assessment calculates that these methane reductions would occur predominantly due to AD plants on pig farms and large dairy and cattle units, a ban on agricultural waste burning and some adjustment in rice cultivation techniques. The NECD targets, based on the GAINS methodology, do not assume any quantitative adjustment in agricultural production, and thus do not give rise to the carbon leakage worries that you refer to in your comment.

Of course, as I mentioned in the post, it seems the realism of the GAINS model estimates are disputed by member states. Also, the immediate benefits for the EU in terms of improved air quality from reduced methane emissions are quite limited; the main benefit is the potential stimulus it would give for international action to reduce methane emissions. For this reason, although I support the inclusion of methane ceilings in the NECD, I also agree considerable flexibilities should be built in to whatever targets are agreed.