On Thursday 27 November 2014 last, the WTO General Council approved three decisions related to public stockholding for food security purposes, the Trade Facilitation Agreement and the post-Bali work programme. With these agreements the hiatus in the WTO’s post-Bali work caused by India’s position on the 2013 Bali Ministerial Council decisions has been unblocked. India had demanded a commitment to faster progress on finding a permanent solution to the treatment of official procurement prices for food security stocks under domestic support disciplines, as well as the copper-fastening of the terms of the interim peace clause, in return for its willingness to approve the Protocol of Amendment to allow the Trade Facilitation Agreement to come into effect.

The drama leading up to these decisions and their significance is well described in this Bridges article. Addressing the General Council , the WTO Director-General Robert Azevêdo said:

By agreeing these three decisions we have put ourselves back in the game. We have put our negotiating work back on track — that means all the Bali decisions: trade facilitation, public stockholding, the LDC issues, the decisions on agriculture, development, and all of the other elements. And we have given ourselves the chance to prepare the post-Bali work program.

It remains to be seen if this optimism is justified or whether WTO members will allow this latest opportunity to conclude the Doha Round to fizzle out. From the agricultural perspective, there are now two issues to be resolved.

One is to agree on the permanent solution to the issue India has raised of how official procurement prices for public stock-holding for food security purposes should be treated under domestic support disciplines. The decision this week suggests that members will make a concerted effort to agree and adopt a permanent solution by 31 December 2015.

The other is to decide how best to pursue the further liberalisation of agricultural trade in the context of the Doha Round mandate with a view to concluding this Doha Round. WTO members have given themselves an extended deadline, to July 2015, to complete a work programme on the outstanding issues. A key question in this context is what role the most recent version of the draft agricultural modalities (called Rev. 4 in WTO parlance) which dates back to December 2008 can play in this process.

A permanent solution for public stockholding

The decision on public stockholding for food security purposes makes one clarification and one amendment to the Bali Decision adopted in December 2013. The clarification concerns the duration of the peace clause, under which WTO Members commit not to challenge another Member’s compliance with its domestic support obligations under the Agreement on Agriculture in relation to support provided for traditional staple food crops in pursuance of public stockholding programmes for food security purposes existing as of the date of that Decision, provided the conditions set out in the Decision are met.

Whereas the original Decision had stated that the interim mechanism (the peace clause) would continue until a permanent solution ‘is found’, the new Decision strengthens this slightly by stating that the peace clause will continue until a permanent solution ‘is agreed and adopted’. It also makes explicit what I suspect all other Members thought they had signed up to in Bali last December, namely, that if a permanent solution to the public stock-holding issue is not agreed and adopted by the 11th Ministerial Conference, then the peace clause continues in place until a permanent solution is agreed and adopted.

The amendment to the 2013 Bali Decision is that Members commit to pursue negotiations on the issue of public stock-holding as a priority and will make a concerted effort to agree and adopt a permanent solution by 31 December 2015. Provision is made for these negotiations to take place in a separate Special Session of the Committee on Agriculture, parallel to the agricultural negotiations under the Doha Round. The Trade Negotiations Committee / General Council will regularly review the progress of these dedicated sessions.

So this leaves just over one year to find, agree and adopt a permanent solution. Possible elements have been put forward by the G-33 group of developing countries and by academic observers. I have reviewed the solutions proposed to date in this paper and summarised them in this presentation.

Front-runners as elements of a permanent solution are some clarification of what is meant by the volume of eligible production in the formula for calculating a product’s Aggregate Measurement of Support, some clarification of how Members can make adjustment for excessive rates of domestic inflation, and the possibility of exempting a price gap when a product’s administered price is less than the tariff-inclusive world market price.

India and the G-33 have also pointed out the absurdity of continuing to use 1986-88 world market prices as the fixed external reference price to measure the market price support element of a product’s AMS. It would certainly make more economic sense to compare a country’s administered prices with the current level of world market prices.

However, I find it difficult to imagine that such a fundamental change in the way of calculating domestic support could be agreed as part of stand-alone negotiations on public-stockholding for food security purposes. For one thing, it would be hard to argue that such a change should be confined to developing countries (and the only guidance in the Bali Decision on the nature of a permanent solution is that it would apply to all developing countries).

And if the basis for calculating domestic support was changed, this would completely alter the significance of the disciplines on domestic support that were provisionally reached in the 2008 draft agricultural modalities and would require their renegotiation. Thus, it appears most likely that any move to change the fixed external reference price would have to be negotiated as part of an extended work programme to conclude the Doha Round.

Future role of the 2008 modalities

The role that the December 2008 draft modalities (Rev. 4 in WTO terms) should play in developing the post-Bali work programme in agriculture remains disputed. This is partly because the draft modalities, although representing very substantial progress in negotiating further liberalisation commitments to that date, were very far from being agreed. Substantial differences remained over the use of the Special Safeguard Mechanism, over the number of Special Products, over the number of sensitive products (mainly an issue for the more highly protected OECD countries), and over the accelerated treatment of cotton.

The other reason why taking up the negotiations where the 2008 modalities left off is opposed by some members is that the world has changed in significant ways since those modalities were constructed. Four issues are pertinent to the agricultural negotiations.

Impact of changes in the world market price level. First, the 2008 draft modalities were constructed just before the 2008 price spike and the realisation that the world market had changed from a situation of low prices and structural over-supply to a situation where world food prices are likely to remain high for a period of years. This structural break in world market conditions has conflicting implications for the negotiations.

On the one hand, it can be argued that, because of high world market prices, it should be easier for countries to accept tariff reductions under the market access pillar and the elimination of export subsidies in the export competition pillar. After all, many countries, including many developing countries, have already lowered their applied tariffs on food imports in response to the changed situation, and export subsidies have virtually disappeared.

The converse of this argument is, however, that the additional benefits of a Doha round for exporting countries have been eroded as they have already received much of the additional market access they sought. This may make them even less willing to accept the corresponding disciplines on their own support policies. Nonetheless, tariff barriers remain important even in the light of the higher world market prices, and a reduction in bound tariffs does have a value in itself even if it does not result immediately in lower applied tariffs.

However, the structural shift in world food markets has exactly the opposite consequence for the negotiations in the domestic support pillar. Here, it makes the existing commitments under the Agreement on Agriculture even more binding, and it makes it more difficult for countries to agree to further reductions. This is the anomalous result of measuring market price support with respect to the 1986-1988 fixed external reference price, even if when measured against the higher world market prices domestic support may actually have fallen.

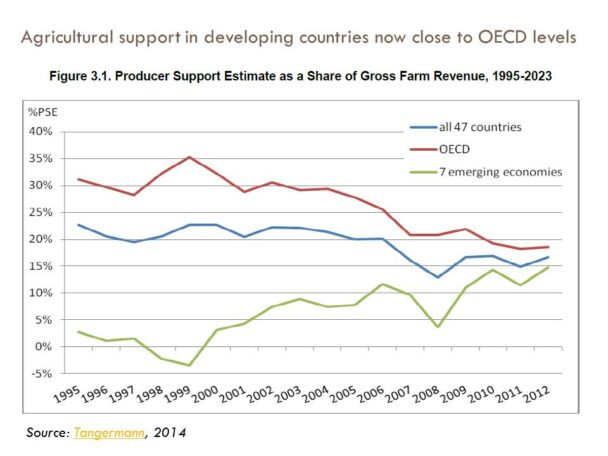

Impact of changes in the trade and agricultural policy context. The second structural change since 2008 is the dramatic increase in trade-distorting policy support in many (but not all) of the emerging economies. The graph below, taken from a recent paper by Tangermann, shows that, measured using the OECD percentage PSE indicator, the average level of support in seven emerging economies is now very close to the average level of support in OECD countries (the OECD includes some high-support developing countries such as Turkey and South Korea as well as low-support developing countries such as Chile and Mexico, so the OECD /emerging economy averages may be even closer today than the graph shows).

The growing weight of policy support in the emerging countries, taken together with their growing role in global agri-food trade as both exporters and importers, has changed the dynamic of the negotiations, in two ways. First, it makes developed countries more reluctant to make commitments to reduce their support when they see support growing so rapidly in the emerging economies.

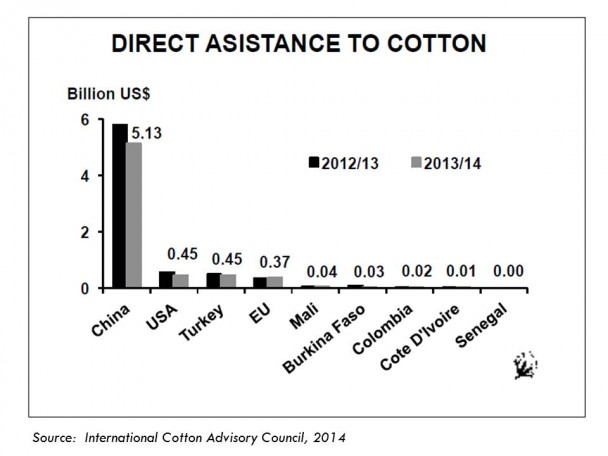

Second, it undermines the narrative that the agricultural component of the Doha Round negotiations is solely a North-South issue. For many developing countries, the real gains from concluding a Doha Round will come as much from disciplining the trade-distorting support of other developing countries. If we take the iconic issue of cotton as an example, the following graph shows just how much the landscape of cotton subsidies has changed since the Doha Round was launched and US subsidies were then the main target of developing country criticism.

Impact of mega-regionals. The third change in the policy landscape which affects the continued relevance of the 2008 draft modalities is the launch of preferential trade negotiations between some of the world’s largest economies, the so-called mega-regionals. These include the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). At this point, the success of these negotiations is not assured.

However, to the extent that, for example, the United States can achieve additional market access for agricultural products through these mega-regionals, its incentive to negotiate a conclusion to the Doha Round is further weakened. It has also been suggested that, because some of those involved in the mega-regionals are aiming at much more ambitious results in these FTAs, they may not be satisfied with the more moderate ambitions of the Doha Round (Singh in this ICTSD book). Again, this suggests that the market access gains envisaged in the 2008 draft modalities may not be sufficient to persuade some countries to accept offsetting disciplines on their own agricultural policies.

For example, a recent review of the impact on the US of the Doha Round draft agricultural modalities by the US Congressional Research Service noted that “a concern of U.S. trade negotiators, Congress, and commodity groups is whether the draft modalities include too many exceptions for foreign importers (in terms of their ability to restrict imports) to ensure that an adequate balance will be achieved between U.S. domestic policy concessions and potential U.S. export gains.”

Disciplines on export restrictions. The final way in which the structural change in global food markets has affected the negotiations is that it highlighted the vulnerability of net-food-importing developing countries to the lack of effective disciplines on export taxes and export restrictions. The 2008 draft modalities did very little to strengthen effective disciplines in this area.

Since the 2008 and 2011 price spikes, in which export restrictions played an important role in driving up global food prices, discussions on how to discipline the use of these instruments have taken place partly in the WTO but also under G-20 auspices.

Prior to the December 2011 WTO Ministerial Conference a group of net food-importing developing countries and least developed countries put forward a proposal which would, inter alia, exempt purchases by these countries from export restrictions. The G-20 Action Plan put forward in June 2011 also addressed the issue of food export restrictions, specifically in the context of food aid. However, a proposal to exempt food purchased for humanitarian purposes by the World Food Programme based on the G-20 initiative failed to win support prior to the 2011 WTO Ministerial Conference. This issue, therefore, remains unfinished business to be tackled as part of the broader Doha Round agenda.

Post-Bali work programme: two views

A huge amount of effort went into developing the Rev. 4 draft agricultural modalities in 2008. There is much that is still relevant and that must be part of any eventual settlement – the harmonising approach to reductions in bound tariffs and domestic support, the elimination of export subsidies, a special safeguard mechanism for developing countries, some role for Special Products, the more ambitious treatment of cotton, flexibilities for sensitive products. I have reviewed the state of play following the Rev. 4 draft modalities in this discussion paper.

However, it did not prove possible to resolve the remaining differences in 2008, so one might legitimately ask, why should it be possible today? Two approaches might be canvassed. One is to narrow the agenda in the hope that agreement might be easier to find on a narrower set of issues, ‘low-hanging fruit’ in WTO jargon. The other approach takes the opposite tack by adding some new issues and widening the agenda. Despite the danger that this latter approach may lead to greater complexity and overload in the negotiations, paradoxically, it also holds out greater hope of success (see also the recent ICTSD e-book Tackling Agriculture in the post-Bali Context and, in particular, the essay by Singh for further discussion of these issues).

The approach of narrowing the agenda was tried in the run-up to Bali, but the experience there showed that it is very difficult to identify a smaller set of issues which all Members can accept as a balanced package. Indeed, the agricultural elements in the Bali package represented a rather meagre result and, given the prominent role of the issue of public stock-holding, arguably overall it represented a step backward rather than forward in terms of trade liberalisation. In particular, Members could not agree to eliminate export subsidies, even though it has long been accepted that this will be part of the overall Doha Round conclusions.

The alternative is to add those issues raised by the changed global market context to the issues covered by the Doha Round modalities. Including additional issues can facilitate an agreement by increasing the scope for bargaining across issues, such that all Members have a greater opportunity to achieve a positive outcome.

In this approach, the emerging countries would accept some narrowing of the scope of their demands for Special Products and the Special Safeguard Mechanism. In return for tighter disciplines on market access (which, as noted above, are now easier to accept because of the higher level of world market prices), they could seek a rebalancing of domestic support disciplines which are increasingly beginning to bite (including a rebasing of the fixed external reference price) as well as some disciplines on the use of export restrictions.

Although a certain amount of work has gone into thinking about the way to approach disciplines on export restrictions, almost no thinking has gone into the rebalancing of domestic support disciplines and the implications of rebasing the fixed external reference price. For different reasons, both the US and emerging economies might welcome a chance to revisit this pillar. This work is now urgently needed if it is to make a contribution to the design of the post-Bali work programme by July 2015.

Without extending the draft agricultural modalities in this way, it is hard to see a successful outcome to the Doha Round agricultural negotiations.

Of course, even if negotiators could conclude a Doha deal on agriculture, this is no guarantee for the overall success of the Round. Difficult negotiations must also take place in the NAMA (non-agricultural market access) and services areas. Also, a Doha deal on agriculture will still leave a host of new trade issues untouched which will need to be addressed in a following round. But without a deal on agriculture, the Doha Round is dead.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.