Last week, the DG AGRI Farm Accountancy Data Network, FADN, made available aggregated data in its public database for the 2012 accounting year. In addition, there is now a Farm Economy Focus, or country fact sheet, based on the 2012 data for each member state which presents key FADN results in a graphical form for a general audience.

The FADN database is a key tool both for policy-makers and researchers seeking to understand the behaviour of farmers and the agricultural economy. The survey does not cover the smallest farms, but it is representative for over 4.9 million holdings across the Union. It contains a wealth of information on the economics of farm businesses, and the FADN team makes it easy to access this information through a very friendly user interface to their public database.

While the FADN tool is a terrific resource, some of the data it contains tell a less-than-encouraging story about the economic condition of EU farming. In this post, I focus on the reliance of farms in each member state on public support and subsidies.

Farmers receive public support through different types of payments. At the outset, we need to acknowledge that there can be a difference between support and subsidy. While support covers all transfers to farmers, the idea of a subsidy implies that there is a benefit to farmers.

However, in some cases, it is possible to argue that, in transferring money to farmers, the public sector is purchasing a range of services of wider value to society. Thus, there is a non-market transaction rather than a subsidy in which farmers receive payment in return for providing non-monetary benefits to the public at large. This rationale is likely to be more important in well-designed agri-environment schemes, and to be virtually absent in untargeted general direct payments.

In what follows, I use the conventional definition of subsidies in the FADN database, but let us keep this distinction in the back of our minds as we examine what the FADN data show.

Importance of different subsidy payments

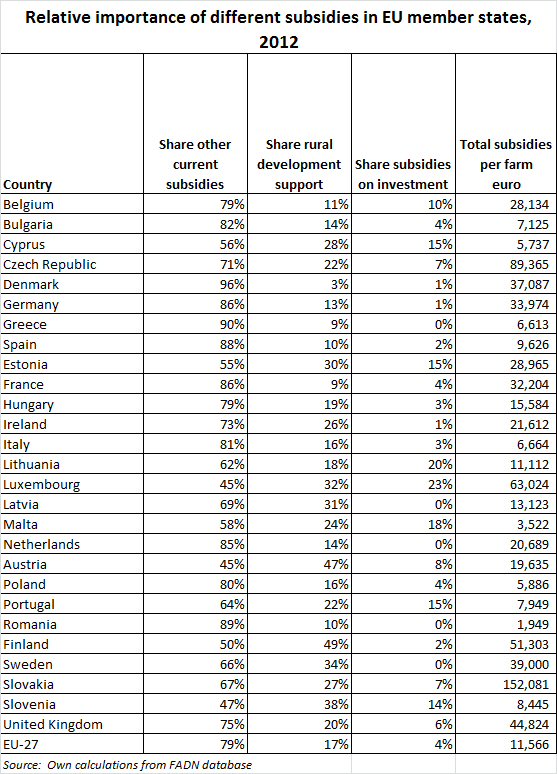

The FADN data allow us to examine the importance of support payments to farmers in each member state. The table below shows both total support per farm in 2012 as well as the relative importance of rural development payments (both EU and national), other current payments (mainly direct payments but also including input subsidy payments), and investment support. There are clear differences across the member states.

First, look at the absolute size of total payments per farm. It is no surprise to see that the largest payments per farm occur in Slovakia and the Czech Republic where large corporate farms play an important role. It is perhaps more surprising to see that each farm in Luxembourg received, on average, €63,000 in subsidies in 2012 (a relevant comparator may be neighbouring Belgium, where the figure per farm is a ‘mere’ €28,000).

The FADN payments include both EU and national payments, so it is not possible to say how much of the support to Luxembourg farmers comes from the EU budget and how much from the Luxembourg national budget (although given recent revelations about how the Luxembourg national budget seems to be financed by pocketing the proceeds of corporation taxes which should have been paid in other countries, it is probably safe to say that most of the support to Luxembourg farmers is paid for by EU taxpayers in one way or another).

The average subsidy received per farm in the EU-27 in 2012 was €11,500. Where countries receive lower payments per farm, this could be either because the total payment envelope per hectare is smaller in those countries, or because the average farm size is smaller.

Note that the three Baltic countries, which receive the lowest Pillar 1 direct payments per hectare, nonetheless all receive total payments per farm close to or above the EU average (in the case of Estonia, where the average farm payment in 2012 was €29,000, the difference is substantial; in the case of Lithuania, the average payment per farm is just below the EU-27 average at €11,100). In interpreting these figures, it is important again to remember that the very smallest farms are not included in the FADN database, so these figures refer loosely to what we can call more commercial farms.

Recalling the debate on external convergence in the recent CAP 2013 reform, these figures show how misleading it can be just to focus on one source of payments to farmers without taking into account the whole picture, as well as the importance of defining what we mean by the farm population.

There are interesting patterns when we examine the breakdown of total subsidies into the three categories. Around 4% of total subsidies are paid as investment subsidies in the EU-27. But in Luxembourg the share is as high as 23%. Why Luxembourg farmers, living in a country with a surfeit of banking capacity, should require such high levels of investment subsidy amounting on average to €14,500 each in 2012 is a mystery.

Other countries with high shares of investment subsidies in total subsidies include some but not all of the new member states, including Lithuania, Malta, Cyprus, Estonia and Slovenia. One surprise is Latvia, where farms appear to receive no investment support at all. Other countries where farms received virtually no investment subsidies include Netherlands, Greece, Romania and Sweden.

There is similar variation in the importance of rural development payments. Rural development payments include less favoured area payments, agri-environment payments and other rural development payments paid directly to farmers. Around one-sixth (17%) of all subsidy transfers are rural development payments in the EU-27, but the shares are highest in Finland (49%) and Austria (47%). Farms in three countries, including France, Greece and Denmark, receive less than 10% of their total subsidies through rural development payments.

The variation in the shares of investment subsidies and rural development payments means that there is also variation in the importance of the remaining current payments. The share is highest in Denmark (96%), followed by Greece, Romania and Spain. The countries with the lowest shares of non-RD current payments include Austria and Luxemboug (with shares of 45%) as well as Slovenia (47%) and Finland (50%).

Importance of subsidies in farm net value added

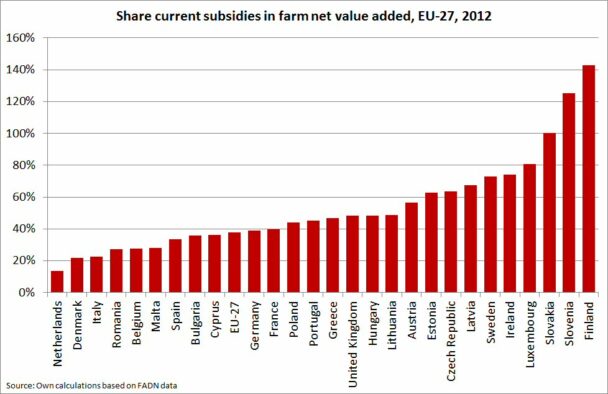

DG AGRI maintains a graph showing the relative importance of both direct payments and total subsidies in farm net value added (what it calls agricultural factor income) on its website. The graph is based on Eurostat agricultural account statistics and shows that total subsidies (which, in this context, includes just rural development and direct payments, but not investment support and some other current subsidies such as input subsidies and disaster payments) as a share of EU agricultural value added was 24% in the period 2010-2012.

The FADN figures, however, suggest that this may be an underestimate. In 2012, the average share of current subsidies (excluding investment subsidies) in farm net value added was much higher, at 38%. As in the DG AGRI graph, there is wide variation between member states, as shown in the figure below.

In three countries, Finland, Slovakia and Slovenia, total subsidies were equal to or greater than agricultural value added. In these countries, the agricultural sector adds nothing to their GDP (except if the subsidy leads to a net transfer from the EU budget which is likely to be the case in Slovakia and Slovenia but not in Finland).

In these countries, farming is a pure consumer good financed by the taxpayer in return for, presumably, the non-economic values it provides. (In the interests of full disclosure, I should mention that I spent some days in Slovenia earlier this summer and greatly enjoyed some of its wines, sausages and cheese).

On the other hand, farms in some other EU countries were much less dependent on current subsidies. The figure for the Netherlands was 14%, and for Denmark and Italy 22%.

Importance of subsidies in farm income

As noted by DG AGRI, agricultural value added:

represents the income generated by farming which is used to remunerate (1) borrowed/rented factors of production (capital, wages and land rents), and (2) own production factors (own labour, capital and land). This concept of income is appropriate for evaluating the impact of changes in the level of public support (i.e. direct payments) on the capacity of farmers to reimburse capital, pay wages and rents as well as to reward its own production factors. This income indicator allows comparison between Member States, because the share of own and external production factors often differs significantly between Member States.

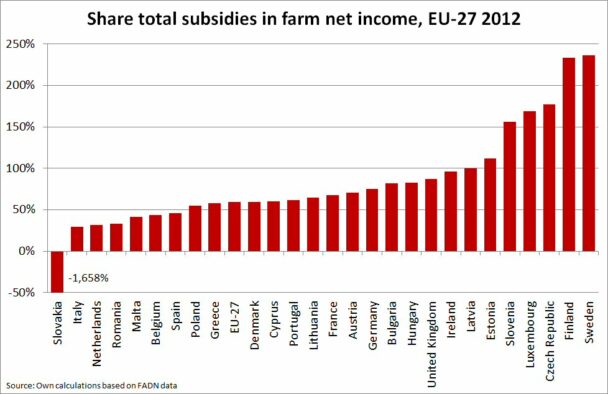

However, it is also possible to express the importance of subsidies in farm net income rather than farm net value added. The relationship between these different accounting concepts is shown in the table below. Farm net income is a better indicator of the income remaining with the farm family after paying for its external factors of production. As shown in the table, investment subsidies are added to agricultural value added to arrive at the farm net income concept. So in comparing the importance of subsidies in supporting farm family income, we must also include investment subsidies as well as current subsidies.

The graph below shows a somewhat different, and even more worrying, picture of the dependence of EU farms on subsidies. The average dependence of farm income in the EU on subsidies is now 58%, and not 38% as in the previous calculation.

Also, note that the Slovakian figure is hugely negative (it is truncated in the graph) as farm net income after paying external factors was negative in that year (recall that corporate farming is much more important in this country than elsewhere in the EU, and the corporate farms were, on average, loss-making in that year).

Apart from Slovakia, other countries where total subsidies were close to or greater than family farm income include Ireland (96%), Latvia (100%), Estonia (112%), Slovenia (156%), Luxemboug (169%), Czech Republic (177%), Finland (234%) and Sweden (236%).

Conclusion

As noted at the outset, support and subsidy may not be the same thing. Farmers can be paid to provide a set of non-market services, such as open landscapes, or maintaining a population in remote regions, or to protect and conserve habitats and biodiversity.

But these figures highlight, yet again, the question whether taxpayers get value for money in the way this money is spent. Can a system in which taxpayers transfer €63,000 each year to each farmer in Luxembourg be justified?

Technical note: The spreadsheet with the raw data and calculations can be downloaded from this link.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

.

Yet again this is a narrow focus on a few figures selected to make some personal point or other. The figures that have been left out include the population of each country. The migration of population. Food security in each country. The political stability or otherwise of each country. Food fraud and the implications of that fraud. The Elliott Review makes some excellent reading. However would all countries in the EU actually be so bothered about such issues? If not then where does this leave us here in England, Wales,Scotland, and N Ireland and Channel Islands? I note you are from the Irish Republic. Given that what do you know about the ABP located in Ireland? Apart from the horse meat incident which also mocks EU regulation and its policing What do you know about Argentinian beef coming into Shannon passed around the markets and then relabelled as Irish or British? (you are closer to Shannon than myself and you say you have been working in agricultural economics for a while – so why the silence on these closely related matters. all of which makes distorts if not mocks the figures you have quoted) When all the evidence is considered where exactly does the EU figures leave us. This is why people in all parts of Great Britain are now thinking local. At least then perhaps the chain of responsibility can be shortened and tracking of food production be better policed. People have been failed by complex government and organisation politics. Control over securing good quality food for a huge population must be a priority for this country. The best control and hence the best food security will come from local sources.

Yet again this is a narrow focus on a few figures selected to make some personal point or other. The figures that have been left out include the population of each country. The migration of population. Food security in each country. The political stability or otherwise of each country. Food fraud and the implications of that fraud. The Elliott Review makes some excellent reading. However would all countries in the EU actually be so bothered about such issues? If not then where does this leave us here in England, Wales,Scotland, and N Ireland and Channel Islands? I note you are from the Irish Republic. Given that what do you know about the ABP located in Ireland? Apart from the horse meat incident which also mocks EU regulation and its policing What do you know about Argentinian beef coming into Shannon passed around the markets and then relabelled as Irish or British? (you are closer to Shannon than myself and you say you have been working in agricultural economics for a while – so why the silence on these closely related matters. all of which makes distorts if not mocks the figures you have quoted) When all the evidence is considered where exactly does the EU figures leave us. This is why people in all parts of Great Britain are now thinking local. At least then perhaps the chain of responsibility can be shortened and tracking of food production be better policed. People have been failed by complex government and organisation politics. Control over securing good quality food for a huge population must be a priority for this country. The best control and hence the best food security will come from local sources.