After much lobbying the Council and Parliament finally agreed that sugar quotas (including quotas on isoglucose) would be extended until the end of the 2016/17 season but would be abolished with effect from October 2017. In January this year, the EU’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) Institute for Prospective Technological Studies published its assessment of what might happen to the EU sugar market as a result of the abolition of sugar quotas. It is worth examining this report in some detail both for its substantive conclusions but also for some insight into the factors likely to affect the EU sugar market balance in the years after 2017.

The JRC study was completed at end-2012. It compares two alternative scenarios in the year 2020 – one scenario assuming that sugar quotas continued (the reference scenario) and one scenario in which sugar quotas are assumed eliminated in 2015. In the latter scenario, three alternatives are simulated with different assumptions regarding the share of isoglucose in the EU sweetener market. The standard simulation assumes no substitution, while the two other simulations assume market shares of 10% and 20%, respectively.

The empirical modelling uses the CAPRI partial equilibrium model. This consists of regional agricultural supply models for each NUTS2 region in the EU27 which determine the level and structure of agricultural production using a mathematical programming approach, and which are linked to a spatial, global partial equilibrium market model covering about 58 commodities and around 60 countries. The version of the CAPRI model used has a 2004 base year, so both the 2006 sugar reform as well as the elimination of quotas must be modelled to derive a reference scenario for 2020.

The CAPRI reference scenario is calibrated to the expected DG AGRI market outlook for 2020 as published in 2011. The JRC report describes the reference scenario as follows:

The simulations show that sugar beet production in 2020, with quotas in force, would be as nearly as high as its 2004 level, despite both the 2006 reform of the sugar regime, which resulted in the net removal of more than 5 million tons of sugar quota, and the cessation of export refunds for sugar in 2008. This implies that other counterbalancing factors, like the increased demand for biofuels to fulfil the renewable energy target for 2020 in the transport sector, are assumed to exert a strong countervailing pressure, replacing virtually all of the renounced quotas for human consumption, much of which had to be exported.

The question the report addresses is what difference quota abolition in 2015 would make to this projection of beet production in 2020.

Reasoning behind JRC results on quota abolition

Under the quota regime, there are two markets for sugar in the EU. The white sugar market for food use is supplied by EU domestic production under quota and by imports. Because of the high MFN tariff on sugar imports, the only imports which are able to access the EU market come from preferential exporters, either exporters which have tariff rate quota (TRQ) access at a low in-quota tariff, or countries which have duty-free access under either the Everything but Arms (EBA) arrangement (all least developed countries) or under the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) with the African, Caribbean and Pacific countries. The price on this market is usually much higher than the world market price because of the high level of tariff protection.

Producers are allowed to produce out-of-quota sugar, but this sugar must be used for industrial purposes (either pharmaceutical uses or bioethanol production) or exported (within limits set by the EU’s WTO commitments). The price received for out-of-quota sugar tends to follow the world market price, as shown in the chart below.

When the sugar quota is eliminated, these two markets will be unified. As a result, the price for white sugar in the food market will fall and the price for industrial sugar will rise until they converge. The detailed mechanisms are described in the report as follows (see also the Technical Annex to this post for a simplified graphical analysis).

Beet (and hence, sugar) production will tend to increase in regions supplying out-of-quota sugar in the reference quota scenario while it will tend to fall in regions that previously produced only quota sugar. The net change in EU domestic production depends on the balance between the additional supply from regions that expand production, and the decline in supply from less productive EU regions, but overall EU production is expected to increase despite the lower price for white sugar. Also, sugar that was previously used for industrial production or for export is now diverted to supplying the food market, so overall EU sugar supply for the white sugar market increases significantly.

Domestic human consumption increases and the JRC report expects total EU domestic use of sugar to increase in the standard scenario (no quota but no isoglucose substitution), but this impact will be small. However, what happens to domestic consumption of sugar will depend greatly on the degree of substitution in the sweetener market with isoglucose.

Currently, the market share of isoglucose is thought to be about 5% of the total EU sweetener market, but this reflects the level of quota and trade restrictions rather than market preferences. In the US, the isoglucose share reaches almost 40% of the sweetener market, but this is not thought likely nor plausible in the EU. The most recent DG AGRI market outlook published in December 2013 projects that isoglusose will have around a 10% share of the overall sweetener market in the EU in 2021, but there is a lot of uncertainty around this figure (Zimmer provides a thorough analysis of the substitution issue here). The higher the isoglucose market share, the lower the expected level of sugar consumption.

With higher domestic supply availability for white sugar and potentially lower domestic consumption, imports fall mainly at the expense of imports from high-cost EPA/EBA countries. The EU’s marginal ton of imported sugar is sourced from this preferential market, and hence it is the marginal supply price of this sugar to EU users (inclusive of transport and marketing costs) that jointly determines the internal EU market price for sugar. The impact of quota abolition on the EU domestic price for white sugar is very influenced by the responsiveness of preferential suppliers to changes in the EU market price.

If preferential suppliers are very responsive, then there will be a rather limited fall in the EU white sugar price but a much larger squeeze on the volume of preferential imports. On the other hand, if preferential exporters are not very responsive to changes in the EU market price (in other words, they want to continue to supply the EU market even at a lower price), then the fall in the EU sugar price will be much more substantial and the reduction in preferential imports will be more limited. The JRC study notes that the supply responsiveness of imports is expected to increase with the narrowing of the price gap between EU and world triggered by the fall in the EU price.

This discussion of the mechanisms likely to determine EU sugar production and the sugar price following quota abolition, drawn from the JRC report, highlights three critical parameters: the overall supply response of EU production when quotas are removed; the likely share of isoglucose in the EU sweetener market when isoglucose quotas are removed; and the responsiveness of export supply from preferential exporters to changes in the EU market price.

What the JRC study concludes

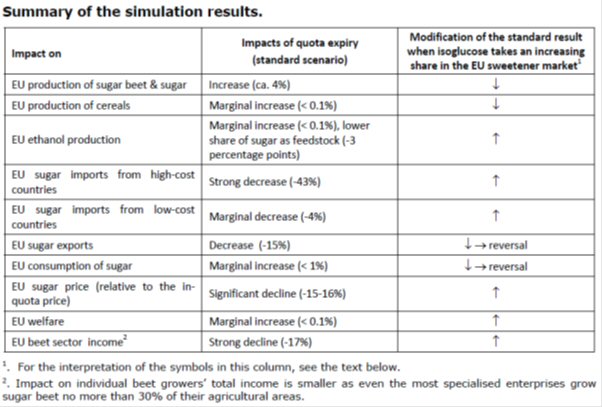

The JRC report summarises its conclusion in the table reproduced below. It focuses on the standard alternative scenario in which quotas are removed but no substitution of isoglucose in the sweetener market is assumed. Because the most recent DG AGRI market outlook estimates a 10% market share by 2021, I also highlight the results from that scenario.

Source: JRC report

Source: JRC report

In the standard scenario, EU sugar production is expected to increase by 4% (compared to the situation in which quotas continue) although with 10% isoglucose substitution this would be reduced to 2%. In the standard scenario, the EU sugar beet price relative to the in-quota price is projected to fall by 15-16%, but this increases to 22-23% in the more likely 10% isoglucose scenario.

In the reference quota scenario preferential sugar imports are estimated at 4 million tonnes. In the standard scenario they fall by 1.6 million tonnes and in the 10% isoglucose scenario preferential sugar imports fall by 2.1 million tonnes or by just over 50%.

There is a substantial negative impact on growers’ sugar beet income, with a projected fall of 17% in the standard no-quota scenario, which would be even higher in the 10% isoglucose scenario. However, the impact on sugar beet growers’ total income is much less, as sugar beet contributes only of a part of their income and there are offsetting positive changes in returns to competing crops. Indeed, in the standard scenario with no substitution of isoglucose, total agricultural income increases (by 0.05%) and this turns into a very small decrease (0.08%) in the scenario with 10% isoglucose.

Overall, the JRC study finds that there is a small positive impact on EU welfare (largely due to an improvement in consumer welfare resulting from lower sugar prices). Most of this welfare increase for consumers is due to their greater purchasing power (because they need to spend less money on sugar or sugar-containing products, they have more money available for other things).

But some of it comes because of a small increase in overall sugar consumption. Whether this should be construed as a welfare increase or not depends on whether we think sugar consumption at the levels currently observed in the EU gives rise to negative health effects which would be exacerbated if consumption were to increase further.

Evaluation

The first thing to be clear about is that the JRC results refer to a comparative static simulation for the year 2020. In other words, the results compare a world without sugar quotas to the world as if sugar quotas had continued to exist in 2020. They tell us nothing about how the sugar price or sugar beet price in 2020 without quotas compares to the current 2014 price with quotas. The fact that beet prices in 2020 might be 22% below the price in a counterfactual reference scenario does not mean that they will be 22% below beet prices as of today; this percentage change could be higher or lower.

The CAPRI model simulates that the average EU in-quota beet price with quotas in 2020 will be €34.2/tonne (although whether this is in 2004 prices which is the base year of the model, in 2012 prices when the simulations were made, or in 2020 nominal prices is not stated). The report steers clear of giving any indication of the likely white sugar price either with or without quotas in that year. Thus, it is not possible to project what the projected 2020 price might be relative to current prices (even allowing for the fact that the simulation removes quotas two years earlier than what will now happen).

Future prices are affected both by the assumptions made in constructing the reference quota scenario and in estimating the impact of removing quotas. As highlighted earlier, the reference scenario is calibrated to the DG AGRI market outlook projections in 2011 which assumed oil prices at USD118/barrel and that the EU 2020 targets for the share of biofuels in transport fuel would be met. Unfortunately, the published DG AGRI market outlook in that year did not include the projections for the sugar market so further information on the implicit reference scenario is not available.

The factors influencing the impact of removing quotas include the net supply response of EU domestic production, the share that isoglucose takes in the overall sweetener market, and the supply responsiveness of the preferential sugar exporters to changes in the EU price.

In order to estimate the net supply response, the JRC modellers need to know the position and shape of the without-quota sugar supply curve. Because sugar quotas have existed since 1968, it is difficult to find empirical data on which to estimate this unobserved supply curve.

The modelling team tried to account for the production of out-of-quota C sugar (whose marginal production cost is generally higher than that of competing crops) by assuming that planned out-of-quota production is an insurance against yield uncertainty (companies want to ensure that they have at least their quota production to process, so in the face of yield uncertainty they contract for more sugar beet hectares than they need to fill their quota with normal yields). However, this could not fully explain quota over-production in some member states, so the JRC team ended up calibrating the marginal cost function to historical beet production data.

Arguably, this approach may underestimate the likely supply response when quotas are abolished. Quotas not only introduced rigidity in production as between member states, but also within member states, as farms traditionally awarded a sugar quota would not easily give it away in the absence of an informal ‘market for quotas’ and financial compensation for the quota transfer. Thus, the production increase following quota abolition could be higher than that estimated in the JRC model.

It is also not clear what assumptions are made about how the price linkage between the white sugar price and the beet price might change after quota abolition. Processing companies are likely to be better able to optimise production and achieve greater economies of scale and this could allow them to absorb some of the likely reduction in the white sugar price. This would also point to higher EU production levels than projected if the study has not taken this effect into account.

Previous modelling exercises of the abolition of quotas underlined the importance of the world sugar price in influencing post-quota EU production and prices. The JRC team in their theoretical analysis argue, in my view correctly, that the main impact of changes in the world sugar price is indirect. The high MFN tariff on sugar means that price formation on the EU sugar market is largely insulated from direct changes in the world market price. Instead, the EU white sugar price is determined by the interaction of the import demand of the EU and the export supply of the preferential sugar exporters (see the Technical Annex for more details).

However, the preferential exporters’ supply curve is partly determined by the world market price, so the latter has an indirect influence on EU market prices. The higher the world market price, the less willing preferential exporters are to supply the EU market at any given EU price, and thus the higher the EU white sugar price. The JRC study does not tell us what world market price is assumed for 2020, so it is not possible to evaluate how their estimated price impact of quota abolition might be affected in the light of updated projections of world sugar market prices in 2020.

Regional impacts

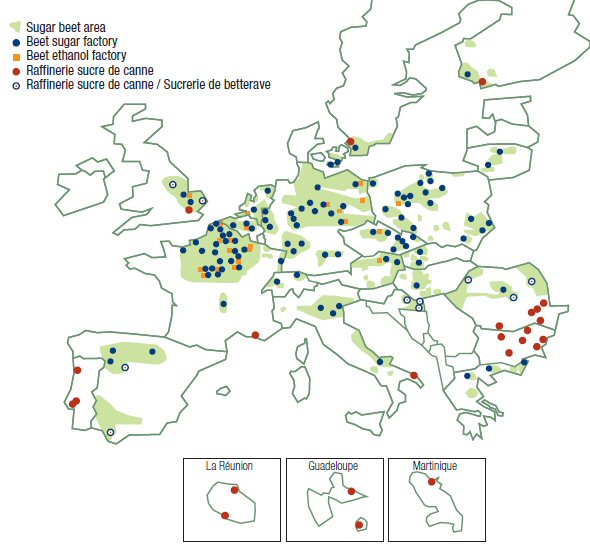

Sugar beet production is highly concentrated in north-western Europe particularly after the 2006 sugar reform. The map below shows the location of sugar beet areas as well as both beet factories and cane refineries. After the elimination of quotas, there is expected to be a restructuring of beet production across Europe. Sugar beet production will expand in the more competitive regions while, in less competitive regions, existing sugar beet farmers will exit the sector.

Source: CEFS,2014

Source: CEFS,2014

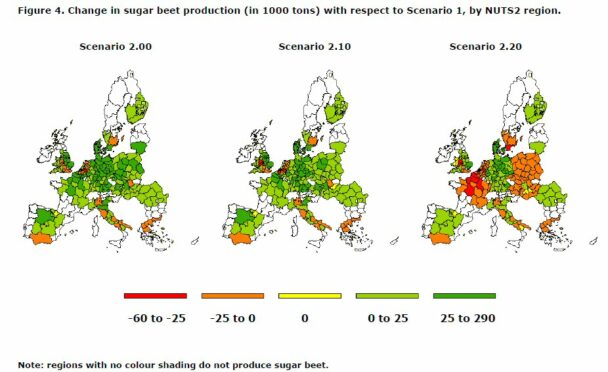

The JRC study indeed finds that impacts at member state level are not uniform. It reports that all member states except Greece and the Netherlands increase sugar beet production, even though beet revenue per hectare falls in all member states except Romania, where it is unchanged. There is even greater variability in production and income impacts at NUTS2 level. In all cases, the consequences at member state and sub-member state level become more negative as an increasing market share for isoglucose is assumed. The projected changes by NUTS2 region are shown in the graphic below for the three no-quota scenarios (2.0 no isoglucose substitution, 2.10 10% isoglucose substitution and 2.20 20% isoglucose substitution).

Conclusions

Under what I consider the most likely scenario, with 10% isoglucose substitution on the sweetener market, the JRC study expects EU sugar beet production to increase by a relatively small 2% compared to its level under the reference quota situation of 20.1 million tonnes (for comparison, production in 2013/14 was 16.9 million tonnes and estimated production in 2014/15 according to DG AGRI is forecast to be 19.6 million tonnes).

Production holds steady despite an expected decrease of 22-23% in the sugar beet price due to quota removal. Because a higher share of the sugar beet previously used for industrial purposes and exports is now sold for white sugar, there is a sharp reduction of around 50% in the volume of preferential imports. This is likely to affect mainly the high-cost EPA producers which may well cease production as they are not competitive on world markets.

As in all modelling work, the results depend on the parameter values used for key variables. The important variables in this simulation are the shift in the EU supply curve in response to quota removal, the supply responsiveness of preferential exporters to changes in the EU price, the level of world market prices, and the share of the sweetener market taken by isoglucose.

Changes in the assumptions made about these parameter values could change the projected outcomes in either an upward or downward direction. There are some reasons to believe that the production response in the EU to the removal of quotas may be even stronger than the JRC team has assumed, implying that the white sugar price and preferential imports could fall by more than what is reported here.

Technical annex

The JRC report contains a very helpful theoretical chapter which uses a graphical presentation to illustrate the various factors which can influence the impact of abolishing sugar quotas. A somewhat simplified and slightly modified version of this analysis can be found in this technical annex to this post.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Photo credit: Wikipedia

This is a very interesting and accurate summary of the common wisdom regarding the consequences of the suppression of quota. At the same time, I cannot share these conclusions, because they are founded on an equilibrium model which, by its construction, avoid taking account of the major determinants of sugar supply, demand and price.

As can be seen from the graph published by Allan, the sugar free price is extreemely volatile. This is not a consequence of meteorological or similar events (the cultuvation of sugar is widely spread over the globe, and the “law of large numbers” should eliminate most of the drawbacks of this source of supply shocks), but the effect of a cobweb-like dynamics.

As a result of this price volatility, risk considerations will become more important than average prices in shaping sugar supply . Such phenomenons will probably decrease supply significantly as soon as quotas will be eliminated. This low supply will trigger prices upsurge, itself leading to optimistic producers reactions, oversupply, and so on…. The resulting price series cannot be periodic (otherwise, large benefits could be derived from countercyclical production, wipping cycle out) . It is thus chaotic (in the mathematical sens of the word), like weather series. It is logically impossible to make long run predictions regarding chaotic series… . The only sound prediction is that, in average, domestic european prices “without” will be significantly higher than “with” quotas. This is not what was expected by the proponents of the quota suppession policy.

See The future of the European sugar market : A case for quotas

(Revised, from the paper presented in the EAAE congress in Ghent, Aug 26-28, 2008)

http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/handle/44069

@Jean-Marc

Thank you for this contribution to the debate, and for highlighting the importance of risk which I agree is not taken into account in the analysis above. There are two issues in your comment.

One is to underline that EU sugar beet prices will be more volatile in future, leading risk-averse farmers to discount somewhat returns from sugar beet production and thus make it less attractive compared to other crops. I agree that, other things being equal, this will tend to dampen the supply response to the removal of quotas. On the other hand, the industry is aware of this and is planning to react.

As one example, Nordzucker in its shareholder magazine Akzente in July 2013 following the political agreement on the CAP reform noted that the end of sugar quotas would mean that Nordzucker and its beet farmers would lose a certain degree of planning security. However, the Chairman went on to note that “new systems of contracts for beet cultivation will be required to be able to manage the two-year period between crop planning and sugar sales without the market regime instruments which had previously applied. Nordzucker will continue to negotiate beet cultivation and delivery terms with the agricultural associations. A key issue will be what forms of price hedging for sugar will be in place in four years. Under consideration are systems such as those commonly used for rapeseed and wheat, for instance.”

If such risk-shifting mechanisms are introduced, then it would help to ameliorate the impact of greater price volatility at least over short-term periods up to two years.

However, your second issue, that we are likely to see the emergence of longer-term cobweb-type cycles would still be valid. In this context, it is worth remembering that the EU sugar market will still be a very managed one, because of the high degree of tariff protection and the possiblity to alter import access conditions in a counter-cyclical way. I would find it hard to believe that the risk issues alone would reverse the conclusions of the static partial equilibrium analysis that prices will fall as a result of quota abolition, but you are right to draw attention to them in this debate. However, as I make clear in the post, saying that prices will fall as a result of the abolition of quotas is not the same as projecting that prices will be lower in 2020 than today – there are indeed many other factors which will influence the sugar market over that period.