In the past few years commentators have emphasised the growing integration between food and energy markets. Food prices were always influenced by energy prices on the cost side, but with the growth of markets for biofuels made from agricultural feedstocks, prices are also linked on the demand side. If oil prices rose, this would tend to pull up food prices as grains, sugarcane and vegetable oils were diverted to fuel production, and if oil prices fell, feedstocks would move back again to the food market also pushing down prices there. The crucial lever here was seen as the Brazilian sugar-ethanol complex and Brazil’s fleet of flex-fuel vehicles, which facilitated easy substitution between the two markets.

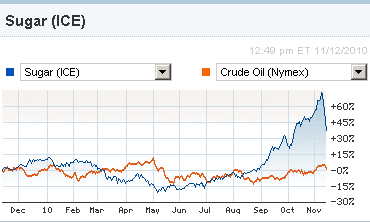

But agricultural markets are subject to their own shocks independent of the energy market, and the price integration is far from perfect as shown by a comparison of sugar and oil prices over the past twelve months. Sugar prices have risen on the back of low stocks, lower-than-expected harvests in key producers and India’s delay in authorising sugar exports until next spring.

What is curious is why the Brazilian ‘arbitrage’ mechanism has not worked. Why is Brazil not taking advantage of the high sugar prices relative to oil to move more of its cane harvest into the sugar market? I don’t know the answer, but possible candidates might include the following. Ethanol prices in Brazil are well below gasoline prices, so the incentive to switch may not yet exist. There may also be mandates in Brazil which prevent the switch. Brazil itself has reduced cane supplies in this harvest, although in itself that does not explain why it does not subsitute now-cheaper oil for ethanol in its cars. Perhaps it simply takes longer than three months for this arbitrage process to work – for the ethanol plants to close down and blend ratios to be reduced. Explanations would be welcomed in the comments section.

Some points to add to my own post above:

1. Czarnikow in a note do suggest that there has been some demand response in Brazil in response to high sugar prices. Also, the US is no longer importing ethanol from Brazil.

2. ERS analysts in an article in Amber Waves make two further points. First, they point out that, because Brazil is the marginal low-cost sugar exporter, the world price of sugar is set by Brazilian costs of production measured in dollar terms. But there is a close relationship between the exchange rate of the Brazilian real and the dollar and the world price of sugar. As the real appreciates relative to the dollar, so does the world price of sugar denominated in dollars.

3. A second point made in the ERS article is that the supply shocks to the world market have just been so big even relative to Brazilian exports that adjustments to the latter alone cannot be expected to compensate.