Reading the UK press over the past few weeks it appears that the UK dairy industry is on its last legs and that UK dairying will soon become an extinct species. The Daily Mail reports that “campaigners warned it was the worst crisis the industry has ever seen”. At the other end of the political spectrum, the Guardian headlines its story “No whey forward – future of Britain’s dairy industry hangs in the balance” and goes on to claim “Years of falling milk prices could spell an end to the fresh, safely produced dairy products we take for granted.”

According to Rob Harrison, the chairman of the NFU’s dairy board, in The Telegraph: “Being a dairy farmer at the moment is like being a boxer – on the ropes and taking body blow after body blow. There is only so much you can take before throwing in the towel.” The House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee has just published a report on dairy prices in response to the alarm.

The papers carry stories of individual dairy farmers and one can only admire their hard work and commitment to their animals. The Guardian interviewed Mark James, who looks after 320 cows in Hertfordshire.

I love the cows. You’ve got to love the cows to do this job. And I believe passionately in dairy farming. I’m proud to be involved in the production of milk – nature’s natural food. When my father first came here in 1968 and started farming the soil was dead, solid and furrowed. Now it’s crumbly and lovely. Yes, it’s hard work but it’s also very satisfying.

The Telegraph carried a piece by Noreen Wainwright who farms 60 cows in the Staffordshire Moorlands.

You keep on milking too because there is some affinity between yourself and the animals, and you can’t imagine the farmyard if the cows were no longer there. You want to keep on doing it as long as you are able to and without being greedy, you want a price that enables you to continue with the job and to live. Deep in the psyche of most farmers is the belief that they are doing a job that is fundamental – producing a basic foodstuff.

The Telegraph also interviewed farmer’s son and Great British Bake Off champion John Whaite:

Although these cows are a business, they have characters you come to know and – dare I say it – love But without a fair price for their milk, there’s no way to pay the business outgoings of a farm: the vet and feed bills, as well as rent, practically inhale money.

The background to these press reports is described by the Daily Mail:

More than 1,000 farmers were not paid for their milk yesterday after a crash in prices plunged the industry into crisis.

The biggest dairy co-operative First Milk delayed payments to its 1,300 farmer members by a fortnight – and cut the price it pays them.

Campaigners warned it was ‘the worst crisis the industry has ever seen’, with little sign of matters improving.

Global milk prices have plummeted in recent months, meaning some British farmers now receive as little as 11.4p a pint (20p a litre) – well below the average 15.9p a pint (28p per litre) it costs to produce it.

Just a year ago farmers could expect to receive 19.2p a pint (34p a litre).

The amount paid to farms is now at its lowest level for eight years, far lower than in 2012, when farmers blockaded milk processors in protest at the low prices they were paid.

Prices and margins in UK dairy farming

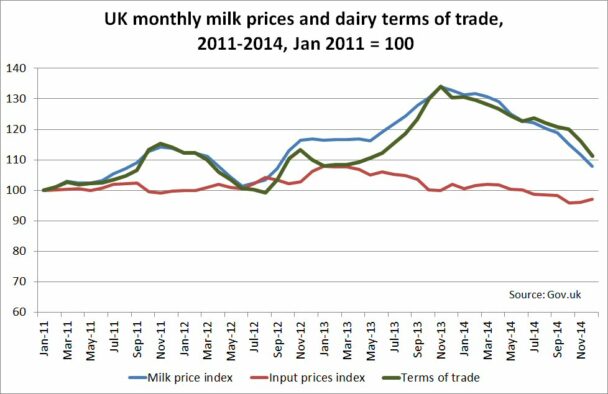

Indeed, milk prices have fallen significantly in the past 12 months, as shown by the official figures from the UK Department of the Environment and Rural Affairs (see chart below), although not as low as the Daily Mail reported. Milk prices have fallen mainly because of greater supply on world markets, compounded in Europe by the impact of the Russian ban on imports on EU dairy products, and in the UK by special factors including the difficulties of the farmers’ cooperative First Milk and, some believe, a supermarket price war on liquid milk.

However, comparing the milk price this month with the price received 12 months ago is a little disingenuous, given that the milk price reached a record high in November 2013. The average milk price in December 2014 of 27.84p per litre, although down 19% on the same month in 2013, still falls within the range of prices that UK farmers have received over the past four years. However, milk prices have continued to fall in January and this month although with the recent upturn on world markets it may be that the bottom has now been reached for this particular milk cycle.

Also, there has been no increase in input costs on average over this period (see next chart). There is no official index of inputs costs for dairy farms alone, so in this chart I have proxied this by the input price index for UK farming as a whole. Looking at UK dairy farmers’ terms of trade (the ratio between their milk price and the cost of inputs) shows that their terms of trade even in December 2014 was still 10% ahead of what it was 4 years ago.

A narrower view of dairy farmer margins (the margin over purchased feed costs) is shown in the next graphic. This chart is based on the average performance of UK dairy herds using Promar Milkminder data. It shows a steep decline in dairy farmers’ margins since the peak in November 2013, partly also due to an increase in average feed costs in recent months, but margins are still close to what they were in 2011-12.

Thus, this evidence does not appear to support the view that there is a generalised dairy crisis in the UK although it may be that farmers supplying the troubled milk processor First Milk face particular problems. Indeed, UK DairyCo figures show that the difference between the highest and lowest milk price paid in the UK increased from 3.73 ppl (pence per litre) in December 2013 to a staggering 11.93 ppl in December 2014, so the average figures conceal much lower milk prices for some farmers.

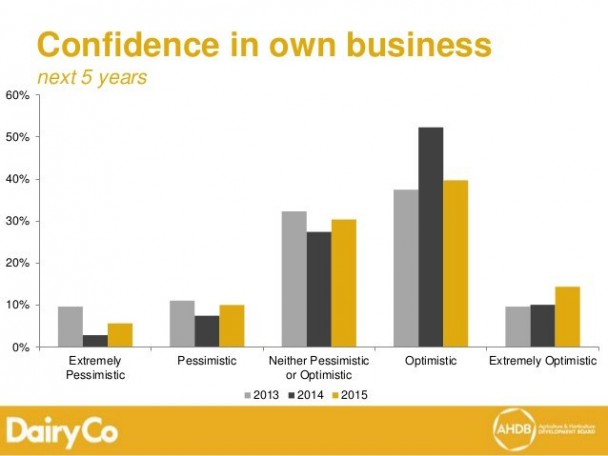

But don’t take my word for it, better to ask UK dairy farmers themselves. This is exactly what DairyCo does in December each year when it asks UK dairy farmers their future intentions. Its latest survey was conducted in December 2014, in other words, following the 19% fall in UK milk prices and with further short-term pressure on prices expected.

According to the survey, the long-term message for UK dairying was still positive, with slightly more farmers being optimistic rather than pessimistic about their own business over the next 12 months, and substantially more being optimistic about their own business over the next 5 years (see chart).

Based on their stated intentions, one-third of UK dairy farmers planned to expand milk production in the next two years. If those farmers do expand then the increase in production will amount to 6%. DairyCo warns that these intentions may be boosted by farmers’ experience of increased production in 2014 due to good weather, and that the further fall in prices in the first two months of 2015 could mean that more farmers may reconsider the future of their business. But, in spite of the talk of crisis, those intending to exit the industry have risen just two percentage points in 2014 to 6% (up from 4% in 2013).

How to explain these contrasting stories?

So, most UK dairy farmers are either optimistic or extremely optimistic about the future of their businesses in the medium-term, yet the press reports tell of an industry in crisis and some individual farmers tell of their difficulties in making ends meet. How are these stories consistent?

One part of the answer, as noted above, is that different farmers receive very different prices for their milk. In December 2014, the average milk price was 28 ppl but the difference between the highest and lowest prices received was 12 ppl. Thus some farmers were receiving 32 ppl and others only 20 ppl. Clearly, those receiving the lowest price for whatever reason are likely to face greater difficulties in making ends meet.

The other part of the answer is that different farmers have different costs of producing milk, and this in turn is driving structural changes in the industry. Dairy farmer costs were monitored in the DairyCo MilkBench+ programme until it ceased collecting data in March 2014. The most recent results thus pertain to the year 2012/013. The survey presents data on the financial results of the top 25% and bottom 25% of participating farmers. In that year, the top 25% of participating farmers received a slightly higher average milk price than the bottom 25% in terms of financial results (30.5 ppl vs 28.5 ppl). However, there was a much larger range of costs incurred (from 27.2 ppl for the top 25% to 39.2 ppl for the lowest 25% of participating farmers. These differences translated into positive net margins of 5.3 ppl for the top 25% group and negative net margins of 8.7 ppl for the lowest 25% group, a difference of 14.0 ppl or around half of the milk price received.

There can be many reasons why costs of production differ across farms. One of the most controversial is the existence of economies of scale. DairyCo have investigated whether larger farms have higher net margins than smaller ones using the 2012/13 Milkbench+ data (see chart). Average herd sizes in the four quartile groups are 85, 157, 205 and 339 cows, respectively.

According to DairyCo:

The analysis found there was a noticeable difference in the level of costs of production between the smaller and larger herds. This was due to the smallest herds having fixed costs 6.2ppl higher than the largest herds, which accounted for almost the entire difference in the total costs of production. Revenue levels (mainly derived from milk price) were virtually the same across all the size quartiles, indicating that fixed costs were the major driver.

The consequence of these figures is that there is pressure on smaller dairy farms to exit the industry. While milk production is increasing, the number of UK dairy farmers is falling. The Telegraph reports that there are now 9,960 dairy farmers left in England and Wales, half the number since 2002. That could fall to 5,000 in the next 10 years. Part of the sense of crisis is that this structural transformation is changing the nature of UK dairying, with the rise of super-dairies in which cows are kept indoors all year around replacing more traditional dairy farms on which cows are turned out to grass every spring and are brought indoors only for the winter months.

As Noreen Wainwright in her Telegraph article wrote:

We do not want to be involved in zero-grazing or mega-dairies. We like it when the cows go out for the summer and literally kick their heels as they run about, taste the grass, and feel the freedom. This is not a romantic view – the cows do appear to love going outside to graze. This means smaller farms where there is enough ground and grazing for medium sized herds; not an intensive, factory approach.

This is clearly an important, and emotional, debate. Do mega-dairies lead to greater environmental problems, greater damage to water quality, greater likelihood of smells, as well as greater stress for the dairy cows themselves? Or, as the proponents argue, are cows actually better off in well-managed barns with round-the-clock care (for an excellent presentation of these arguments, it is hard to beat this terrific piece of journalism by Jon Henley entitled ‘The battle for the soul of British milk’ which appeared in The Guardian last October; the animal welfare arguments are set out by Compassion in World Farming here).

Is milk sold too cheaply?

Whatever the merits of either side of this debate, it is hard to understand the logic of campaigners who want to see higher prices for milk in supermarkets as a way to safeguard farmers’ incomes and to prevent this structural change. Note, this is a separate issue to whether the full costs of milk production, including impacts on water quality and greenhouse gas emissions, are fully factored into farmers’ costs and thus the current milk price; that is a different argument.

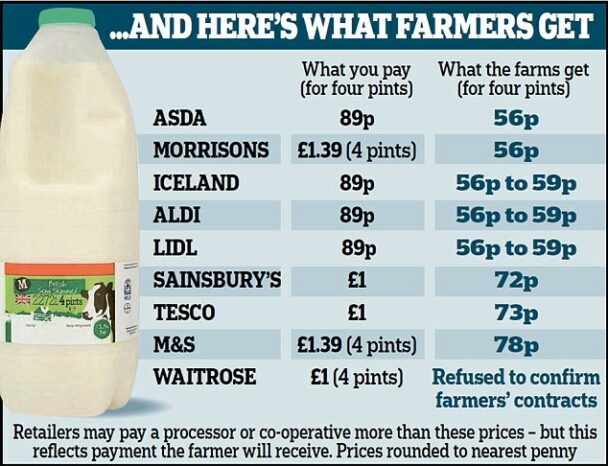

The argument in the UK is that supermarkets are selling milk ‘too cheaply’ and should pay higher prices to farmers (current prices are shown in the Daily Mail graphic below where Tesco. M&S and Sainsbury’s pay cost-related prices to farmers while other supermarkets pay market-related prices, and M&S also make animal welfare-related payments).

I always get a funny feeling when I hear the relatively well-off demand that low-income households should pay more for their food to satisfy the preferences of the better-off (this is, of course, a generalisation and exceptions exist, not least dairy farmers just breaking even, but it is broadly true). For households trying to make their grocery bills stretch, low milk prices allow them to purchase a nutritious product in quantities that they otherwise could not afford. The solution to this dilemma is to encourage the marketing of milk products which reflect the preferences of the better-off and thus command a premium price.

This can be done either by a supermarket chain branding its own products as a premium brand (as M&S does in the UK) or through certifying that a product meets certain production process standards through labelling (for example, organic), allowing households to balance their preferences against their budget constraints. In Denmark, 30% of all liquid milk sales now consist of organic milk, indicating that a substantial proportion of households are prepared to pay a premium for the qualities involved in organic milk production which includes the maximum use of grazing.

Another option open to those who feel more strongly about the non-price attributes of milk and are willing to pay more for these is to support alternative distribution channels, such as direct sales or deliveries.

The injustice of taxing the poor to pay for the preferences of the better-off is compounded by the ineffectiveness of price increases in stemming the structural change. Raising the price of milk to farmers will make a small difference to the smaller dairy farmer, while creating super-profits for the larger farms which already produce competitively at existing prices. The very farmers which campaigners seek to thwart will be the main beneficiaries if supermarkets are required to pay a higher milk price by whatever means.

Dairy farmers certainly face challenges. Milk price volatility is a new problem and one which is here to stay, so farmers must be encouraged to develop risk management strategies to deal with this. UK dairy farming, as in other EU countries, is likely to become increasingly diversified between larger-scale farmers competing on cost and smaller-scale farmers developing premium products sold on short supply chains.

However, contrary to recent press speculation, the future for UK dairying seems secure. Commissioner Phil Hogan’s remarks at January’s EU Agricultural Council that the EU’s dairy sector “is not in a state of crisis” applies equally well to the UK.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Sorry can’t resist it:

1. Problem one. In the UK it is not liquid milk that is the main issue

but the value for processing and thus the impact of the world market.

Contract range increases in these circumstances.

2.Our big supermarkets are under threat form the the discounters who are not so interested in the complexities of say fair trade or choice. Our major supermarkets in general pay the most for liquid milk.

3. Our most important product Cheddar cheese is so universal that we

can’t even associate it with the UK so no protected name status or price

differential for a UK good in contrast to other national cheeses.

4. Historically liquid milk price supported the other milk sectors. When I

first came into the industry with the Milk Marketing Board monopoly ONLY

liquid milk buyers and chocolate chip manufacturers paid more for their

milk than the farmer received. In a monopoly situation liquid milk demand

is price inelastic.However, I do not believe that people should be expected to pay more for a fundamental than they should

5. Farm efficiency is far too variable and costings often give the wrong

impression, for example, whether labour and rent is real or imputed. The supply chain is also a problem operating under a much greater efficiency range than should be the case.

.

6. Thesis. Revolution usually occurs not when the situation is at its

worse but when things have been dire, get better and look as though they

are returning.

7. Cows like to be out – but you should also see them queuing up to come

back in when it is cold and wet!

Thank you for making sense of all the noise! I have a question:

‘For households trying to make their grocery bills stretch, low milk prices allow them to purchase a nutritious product in quantities that they otherwise could not afford.’

Is there any research supporting this statement?

E.g. when a household of 4 would consume 4 pints a day, it would be (1.39-0.89) (=the most expensive minus the cheapest price for fresh milk in the UK) x 30 days = max. 1500 p. per month. And in fact, when you look at the dairy recommendations (ca. 500 g/person/day for all dairy products), it would actually amount to ca. 2 pints fresh milk per day (GBP 3.50 per month) and 2 pints in the form of other dairy products. I don’t want to argue that paying 3.5 GBP per month extra for fresh milk is not significant, but I think it could be considered for the sake of the environment, animal welfare and, not least, for economic reasons related to dairy farming.

In fact, considering that an average person in the EU consumes twice the recommended amount animal protein and fat, we could actually save some money on the food budget, be more heathy and relieve the environment a bit while paying a bit more for good food.

Thanks for your thoughts.

@Simon

Thanks for those useful reflections. You are right to stress that liquid milk only accounts for half of UK milk sales, and the other half goes into dairy products of various kinds whose price is more sensitive to world market fluctuations. Much of the press comment in the UK focuses on the pricing of liquid milk in supermarkets as a factor in the fall in producer prices and I wanted to address that in the last part of my post. You are also right to emphasise that cost of production calculations are based on assumptions which can be criticised, but I think we agree with the basic conclusion that they are highly variable across farms (as well as processors and other agents in the supply chain) and that economies of scale are an important contributor to that variation.

@Liesbeth

Thanks for your comment which allows me to explain my argument a bit more precisely. You rightly question whether cheaper milk would encourage low-income households to purchase a larger quantity and, if so, whether that would be a good thing. In fact, the evidence suggests that the demand for liquid milk in the UK is very inelastic with respect to price, in part because most liquid milk is consumed with another product (milk with cereals, or milk with tea) (this argument is made in the evaluation of the EU school milk scheme ec.europa.eu/agriculture/eval/reports/schoolmilk/8.pdf).

What I meant to say (should have said) is that cheaper milk allows low-income families to stretch their grocery budgets further, which is not an insignificant issue for many households. Unfortunately, making ends meet is a challenge for an increasing number of families in Europe today – Eurostat estimates that almost 10% of the EU population are ‘severely materially deprived’ meaning that they are struggling to pay their rent or utility bills or cannot afford to take a one week holiday from home. The latest crisis report from Caritas Europe (http://www.caritas.eu/news/poverty-and-inequalities-on-the-rise-people-need-fair-solutions) estimates that 1 in 3 children in Europe live in poverty. Usage of food banks is on the rise. Against that background, low-priced milk helps family budgets go further.

However, I made clear in my post that where there are negative externalities associated with milk production these costs should be internalised in the price of milk. This includes environmental costs including greenhouse gas emissions. My understanding is that animal scientists do not conclude that zero-grazing systems are necessarily bad for animal welfare, thus whether one wants to purchase milk from grazing cows or indoor cows is a value judgement and a preference, not an externality. Those consumers who prefer to purchase milk from grazing cows and have the means to do so can do so by purchasing premium milk products, without raising the price of milk for those families with more binding budget constraints.