The British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson revealed his four ‘red lines’ in the Brexit negotiations in an interview in The Sun newspaper recently. They include:

1. The transition period post-Brexit must be a maximum of 2 years and not a second more

2. UK must refuse to accept new EU or European Court of Justice rulings during transition

3. No payments for single market access when transition ends

4. UK must not agree to shadow EU rules to gain access to market.

On the budget payments issue, Johnson explained: “What I have always said is that we will pay for things that are reasonable, scientific programmes. But when it comes to paying for access to the market, that won’t happen any more than we would expect them to pay us for access to our market.”

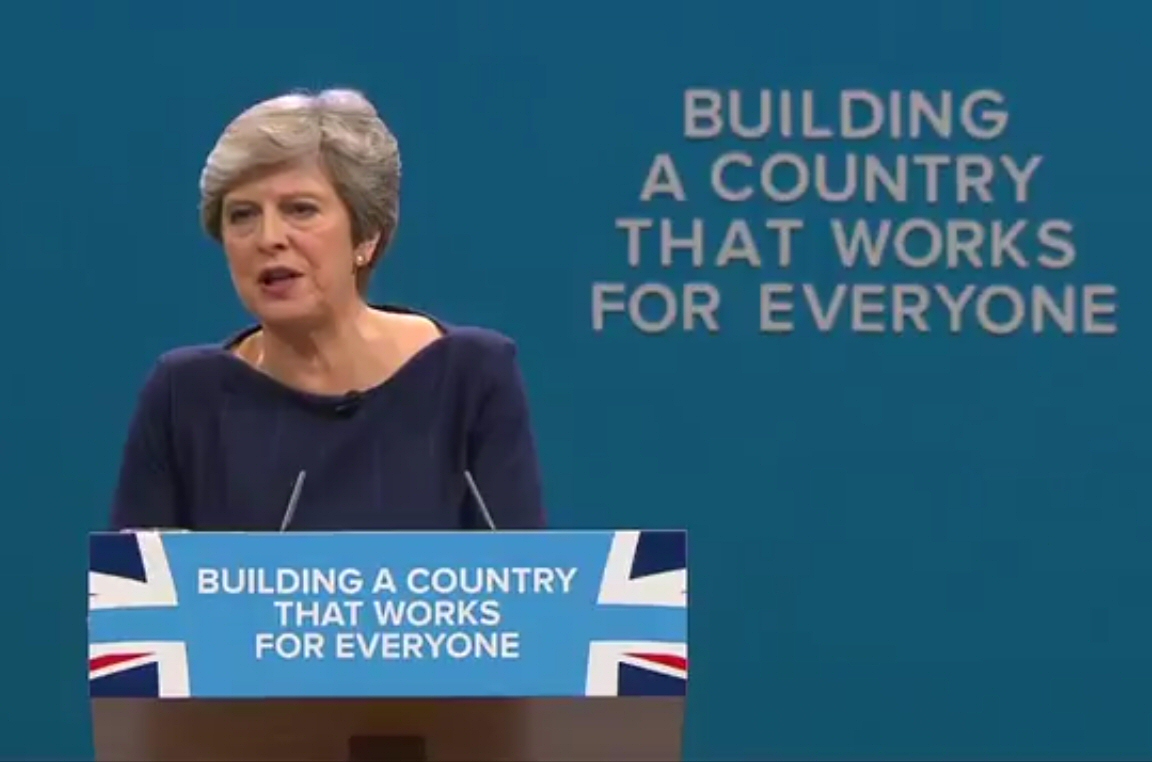

That the UK might continue to have access to the single market but not contribute to the economic and social cohesion of this market was a widely-heard refrain at the fringe meetings during the recent Conservative Party conference. As in many other areas, it demonstrates the woeful ignorance among the current British political class of the history of the EU and of how the EU operates.

Economic and social cohesion a complementary goal to the single market

The link between the single market and ‘paying for access’ goes back to the Single European Act which was agreed in 1986 as the first amendment to the original Treaty of Rome. The Single Act brought about the creation of the EU internal market which was to be completed by 1 January 1993. This built on and broadened the idea of the common market introduced in 1958 by tackling the issue of non-tariff barriers to internal EU trade.

The Single Act also introduced a new title in the EU Treaty on Economic and Social Cohesion. This explicitly established for the first time the principle of solidarity between Member States. Article 130a (now Article 174 of the Lisbon Treaty) stated that the Union ‘shall aim at reducing disparities between the levels of development of the various regions and the backwardness of the less favoured regions’. Article 130b (now Article 175 of the Lisbon Treaty) required the Member States to take cohesion into account in conducting and coordinating their economic policies. It also provided that the implementation of the common policies and of the internal market and, more particularly, assistance under the Structural Funds, should contribute to the objective of cohesion.

This essential link between the single market and economic and social cohesion had been underlined in a declaration issued following the European Council meeting in June 1987 by all the national delegations except the United Kingdom which stated inter alia that:

one of the essential tasks of the Community is to establish a common economic space comprising the realization of a single market and economic and social cohesion. The realization of the single market, in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is insured, will be the cornerstone of that common economic space. The convergence of the economic and monetary policies of the Member States, and notably the strengthening of the EMS, are essential elements of that space. The creation of the economic space will necessitate the development of flanking policies in order to realize a greater cohesion of the Community on the base of the dispositions of the Single Act.

Gilles Grin in his book Battle of the Single European Market (p. 133) notes:

Economic and social cohesion held a very important place in the quoted declaration because there was a fear that the weaker economies of the Community – in particular Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain – would not be able to cope with the consequences of large-scale liberalization if they were not helped. For instance, during a meeting with Francois Mitterand, the Spanish President of the Council Felipe Gonzalez, expressed his worries with strong words: “I am preoccupied about the realization of the internal market: at home there will be social repercussions, there will be an economic and social cost of this internal market. This cost will have to be settled, either in national budgets or in the Community budget. We will not be able to withstand the shock if, in parallel, one does not put into place complementary development actions. The internal market is going to provoke a dualization of European economies, and this I cannot accept”.

In practical terms, this link between the further opening up of national economies and the concern to ensure that all regions and Member States would benefit from this move was operationalised with a doubling of the Structural Funds in 1993 to accompany the full introduction of the single market.

The UK did not sign up to the European Council conclusions in June 1987 but as these covered a broad range of budget and other issues it is not clear whether it objected specifically to the link made between the single market and support for cohesion policies or not.

In any event, when the UK rebate was up for discussion in 2005 in the context of agreeing the EU Multi-annual Financial Framework for 2007-2013, then UK Prime Minister Tony Blair agreed to exclude the UK’s contributions to non-CAP Pillar 1 agricultural expenditure in Member States that acceded to the EU in or after 2004 from the calculation of the UK rebate from 2011 onwards. In other words, the UK government in 2005 agreed to “disapply” the UK rebate on non-agricultural expenditure (including Pillar 2 rural development spending) in new Member States, accepting that the UK would pay its full share in financing transfers to these countries to help prepare them to share in the benefits of creating a common economic space (the rebate continues to apply to CAP direct payments and market-related agricultural spending in these countries which does not have this justification).

This principle was extended to non-EU countries that became members of the European Economic Area (EEA) in 1994 and also benefit from the ability to trade without barriers in a single internal market. Thus, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, and later Switzerland under its bilateral agreements with the EU, make budget payments towards economic and social cohesion in the single market.

The EEA and Norway Grants

It is important to underline that Norway and the other non-EU countries do not make payments to the EU budget in return for access to the single market, as is often wrongly stated.

Multi-year funding schemes by the EEA EFTA States have been in place since 1994 under the EEA Financial Mechanism. These are now known as the EEA Grants and the Norway Grants schemes. The EEA Grants are jointly financed by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway (the EEA EFTA countries) and are available to the 13 EU member countries that joined the EU and the EEA in 2004, 2007 and 2013 as well as Greece and Portugal. The Norway Grants are financed solely by Norway and available in 13 EU member countries that joined in 2004, 2007 and 2013.

The Financial Mechanism was established by the EFTA States under the EEA Agreement with a view to reducing social and economic disparities in the EEA, and to put the beneficiary countries in a better position to make use of the internal market. The provisions of the Financial Mechanism are set out in Protocol 38 to the EEA Agreement which is regularly updated at multi-year intervals. Revisions to the Protocol are jointly agreed by the EU and the three EEA EFTA states. The Protocols set out the financial contributions to be made, the priority sectors to be supported in the beneficiary countries, the allocation of funds between beneficiary countries and the share of national co-financing required.

The EFTA states (Donor States) sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with each of the beneficiary countries which sets out the multi-annual programming framework and the structures for management and control. EEA grants are administered by the Financial Mechanism Committee (FMC) under the EFTA Standing Committee. The FMC is composed of representatives from the Ministries of Foreign Affairs from Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. The Financial Mechanism Office operates as the secretariat for managing the Grants on behalf of these donor states. On the basis of the MoUs, the beneficiary states make proposals for specific programmes to the EFTA states. It is up to the EFTA states to approve the proposals and to conclude grant agreements with the beneficiary countries.

The EU does have some influence on the process. Apart from jointly agreeing the multi-year Protocols, consultations with the European Commission take place at a strategic level during the negotiations of the MoU with each beneficiary. The intention here is to promote complementarity and synergies with EU cohesion policy. The European Commission screens all programmes and any substantial change(s) in a programme for their compatibility with the European Union’s objectives. The results of the screening, as well as any comments issued by the European Commission preceding the conclusion of the screening, shall be taken into account by the FMC. Further, on explicit request from the EFTA states or the beneficiary state concerned, the European Commission can be asked to undertake a screening of a proposal for a specific programme before its adoption, to ensure compatibility with the European Union’s cohesion policy. However, on a practical implementation level, the administration of the EEA grants is in the hands of the EEA EFTA states.

In the five-year period from 2009 to 2014, the three EEA EFTA countries contributed €1.8 billion towards economic and social cohesion within the EEA. Over the seven-year period 2014 – 2021, they will be contributing a further €2.8 billion, of which Norway will be paying 97%. Although I could not find a precise formula, these contributions are apparently calculated in accordance with the gross national product at market prices of the EEA EFTA states using data for the last three calendar years

The Swiss experience

Since 2008, Switzerland participates in various projects designed to reduce economic and social disparities in an enlarged EU, with CHF 1.302 billion (€1.19 billion). The legal basis for Switzerland’s contribution to EU enlargement is the Federal Act of 24 March 2006 on Cooperation with the States of Eastern Europe which was approved by a referendum by the Swiss people in November 2006. As the Swiss government website notes:

In doing so, they signalled their approval for financial support aimed at reducing economic and social disparities in the enlarged EU. For despite the rapid growth that characterised the years immediately following EU membership, the level of prosperity in the new EU member states is relatively low and the gap with EU-15 member states is comparably wide.

In turn, the Swiss government contribution is governed by a bilateral framework agreement signed by Switzerland and the beneficiary countries in central and eastern Europe. Again, the website makes clear that this money is not a contribution to the EU budget:

It is misleading whenever either the term “Cohesion Fund” or “Cohesion Payment” is used instead of the term “Enlargement Contribution” because these terms are normally used to refer to the instruments of the EU’s cohesion policy. The Swiss enlargement contribution is not part of the EU’s cohesion policy, nor does Switzerland make any cohesion payments to the EU. With its autonomous enlargement contribution Switzerland finances specific, high quality projects with the aim of reducing the economic and social disparities in the 13 new EU member states. In this way, it supports the EU objective of strengthening the economic and social cohesion (to be understood as internal cohesion), and it does so in its own particular way. Indeed, the projects are bilaterally agreed upon with each individual partner country, with Switzerland making the final decision on approval of the financing. In addition, the projects are closely monitored by Switzerland, for instance by way of its own contribution offices in the country concerned.

The Swiss contribution is an integral part of Swiss foreign policy on Europe which aims to consolidate Switzerland’s relations with the EU and its member states. The positive way in which Switzerland views its contribution to economic and social cohesion in the single market is underlined by the following official quotation:

Switzerland’s contribution to EU enlargement consolidates bilateral relations not only between Switzerland and the new EU member states, but also between Switzerland and the EU as a whole. The success of Switzerland’s efforts to safeguard its interests in Europe also depends on its ability to project itself as a partner aware of its responsibilities and ready to share the cost of Europe’s development. Close relations and cooperation with the EU is crucial, since about one franc in three that Switzerland earns comes from trade with the 28 EU states.

With its enlargement contribution, Switzerland establishes advisory and institutional partnerships between government authorities, non-profit organisations, trade associations, interest groups and social partners from Switzerland and partner countries. This cooperation encourages the exchange of knowledge and experiences, and strengthens Switzerland’s local presence.

Conclusions

In summary, the EEA EFTA states and Switzerland do not make contributions to the EU budget in return for access to the single market. They do make contributions directly to the less prosperous Member States in the single market with a view to reducing economic and social disparities within this common economic space. Within any economic space, there are likely to be centripetal forces drawing economic activity and resources towards the core and more economically advanced regions to the detriment of more peripheral and less advanced regions. Cohesion policy is designed to counter this trend to ensure that all regions can benefit from participation in the common economic space.

The British Foreign Secretary is clearly unaware of the background to these contributions to the less prosperous EU Member States. UK budget contributions as part of single market access post-Brexit would not be a contribution to the EU budget. They would be similar to the UK’s foreign aid budget, the payments would be made under UK control although coordinated with EU cohesion policy for sensible reasons, and they would continue the long-standing UK policy of support for the economic development of the less prosperous countries in central and eastern Europe.

The Foreign Secretary’s position is based on an ignorance of history and of the way key institutions in Europe actually work, and is at variance with the UK’s expressed values and interests. Unfortunately, it may yet jeopardise the future relationship between the UK and the EU after Brexit.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

The UK is actually unable to be a member of a “free” trading zone like the EU for the same reasons Switzerland and Norway can’t be members. These three nations in Europe have the largest problem on the domestic food capacity front.

Norway has plenty of fish, but almost nothing else (leaving aside petroleum for a few decades). It has no raw materials, and no infrastructure to support industry. When petroleum is finished, the fish exports have to pay for everything this country imports. The Norwegians know this, and they have to limit imports of everything by making it expensive. Food in Norway costs 2-3 times as much as in Sweden and cars are check at borders to make sure Norwegians don’t exceed their quotas. Cars have a 100% import duty… They could be a member of the EU now, but not anymore when the oil is finished.

Switzerland has a 50% deficit in food. If they joined, and used the CAP etc. to protect their hugely inefficient and meagre food sector, they could not cope with membership because for every Swiss the border is only an hour drive away. Food in Switzerland today costs 3-4 times as much as in neighbouring countries. Every Swiss has a weekly limit on how much food they can bring in and the Swiss customs searches every Swiss car coming in for food the way the Stasi searched cars leaving East Germany did for people some 30 years ago. If they joined the EU and had to cope with not just a inflood of food, but also MiFir directive that stipulates the sharing of bank account information, Switzerland would quickly disintegrate as a sovereign nation.

The UK has at least a 50% food deficit, plus the fact that the poor in the UK get half their calories from refined sugar. The UK’s desire for exit is rooted in two factors. They never cared for home based agriculture because no matter how much they did care, their lands produced so little. Before WWII they used colonial revenue streams for 100s of years to generate gold which they then used to buy French food. After WWII, they lived off American aid and had war time food rationing in place until 1955, which is when they started to see revenue from their new invention. Offshore banking and financial services. It went fine, and eventually they even joined the EU, and then the sector was booming until the 2007 crash and the UBS-IRS scandal that started to shed light on what Offshore banking really means.

As Brussels started to clamp down on tax evasion, and pushed through MiFir in 2015 that comes into effect in on Jan 3, 2018, it was clear to them that they had to exit. Without being able to offer Secret Offshore banking to tax evasion minded EU residents, they realized that national bankruptcy was on the horizon if they remained in the EU. The problem is for the UK (and for the EU) is that the UK has no answer for how they will earn the export income needed to feed 62M people on an island that has capacity to feed maybe 25. They must have nasty tricks in mind, as the most important thing for the Brexit champions seems to be to get away from the subpoena powers of the EU supreme court. The EU should be more worried about what will come out of London after Brexit, then about getting the divorce bill settled. You can do quite interesting things in the unregulated markets for securities if you have access to the raw data feed of the GCHQ and NSA that records every conversation on the planet…