A new study from the University of Wageningen in the Netherlands has attempted to model the effects of the abolition of EU farm subsidies. The authors of the report state that their study is very much a ‘worst case assessment’ since,

“It does not take into account farmers’ behaviour, although the past has shown that farmers do adapt to changes in the Common Agricultural Policy. It also assumes a fixed cost structure and abstracts from changes in factor prices and structural change, all elements which would reduce the impact of reform on farm incomes.”

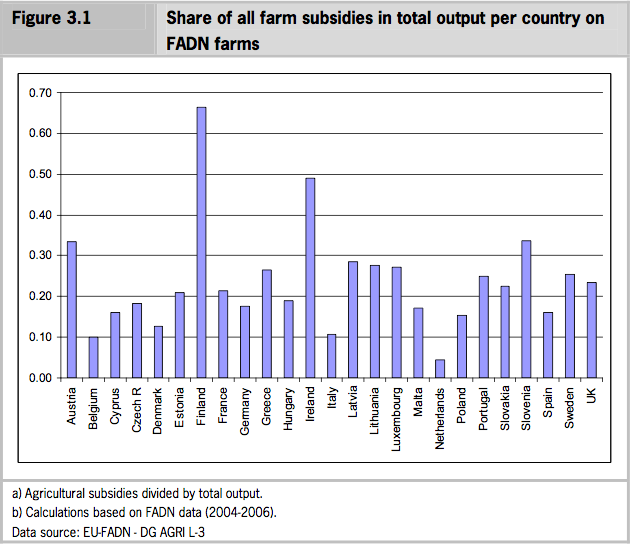

The report makes it clear that the effect of subsidies – and their removal – is not felt evenly across Europe. In countries such as the Netherlands, Italy and Belgium the share of farm subsidies in total agricultural output is below or around 10%, in Austria and Slovenia above 30%, in Ireland around 50% and in Finland even above 60%.

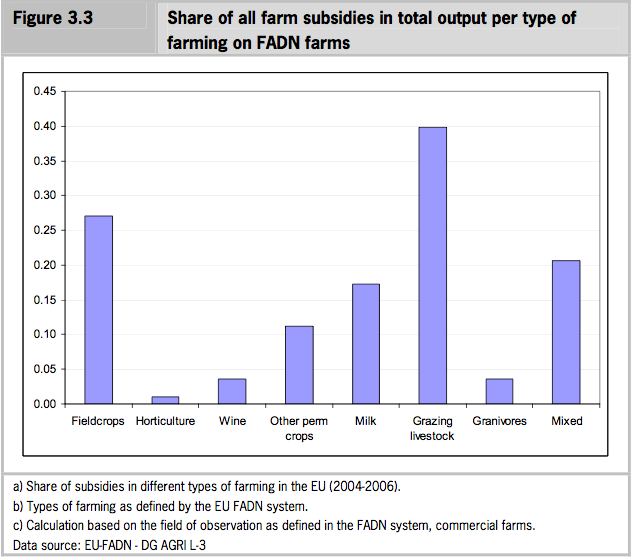

The level of subsidies in the grazing livestock sector is the highest, followed by the arable sector. The horticultural sector, and to a lesser extend the wine and intensive livestock sector receive the lowest amount of subsidies related to total output. As the report puts it, “the ‘non-CAP types of farms’ (e.g. horticulture, permanent crops and intensive livestock) have, in general, better prospects than the ‘CAP types of farms’.” Unfortunately, the ‘CAP types of farm’ account for some 95 per cent of EU land devoted to agriculture and so “the deterioration of the viability of these farms as a result of the abolition of the subsidies may have a serious impact on the structure of the farm sector as well as on the vitality of rural areas.”

The report concludes:

“The viability of farms in Spain, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Belgium and Austria is hardly affected [by the removal of subsidies], whilst farms in Denmark, Ireland, Sweden and the UK, as well as farms of some types in France, Germany, Hungary and Slovakia are heavily affected. In these countries, abolition of decoupled payments results in a large share of farms with negative farm incomes.”

The analysis looks only at first-order impacts and makes no attempt to predict how farmer behaviour might change were subsidies to be abolished. Even so, the authors point to evidence suggesting the adaptability of agriculture to policy change. For instance, arable Netherlands reacted to decoupling of arable payments and reduction of EU sugar subsidies by growing more intensive crops such as potatoes, vegetables and flower bulbs and less cereals and sugar beet. The authors point out that European farms have long been consolidating into larger units, in response to technological change and market competition. Abolishing subsidies would speed up the existing process of ‘structural change’, says the report.

Finally, the report attempts to reach some conclusions about which kinds of farms are best-placed to weather the economic storm that would come with the abolition of subsidies. The report finds that farm size has a bearing on viability but it can work in different ways.

“The direction of this relationship differs between countries. In countries such as Germany, Latvia and Hungary larger farms tend to be less vital. In these countries the cooperative farms are an important reason for this. In other countries such as Belgium, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands and the UK larger farms tend to be more vital.”

The authors point out that the two main potential problems that would be caused by the abolition of current subsidy system – land abandonment and farm insolvency – could be addressed at less cost than at present with a more targeted approach. This is perhaps the most policy-relevant conclusion of the entire report.

Read: Farm viability in the European Union: Assessment of the impact of changes in farm payments