Farming protests are currently taking place in several European countries. Several reasons are advanced for what is prompting these demonstrations – concerns over incomes and rising costs, the burden of additional environmental regulation, free trade agreements with third countries, the uncertainty arising from increasingly volatile weather conditions, the sense that society no longer values the work of farmers in the same way as in the past. No doubt all factors play some role, but in this post I want to dissect the farm income context. I make use of a chart that I posted on my X and LinkedIn feeds a little time ago, but a blog post allows me to give some additional background.

We frequently hear that farmers’ incomes across Europe have been under pressure from a variety of factors, ranging from strong price fluctuations to rising production costs and extreme weather phenomena. The basic message of the chart (which I reproduce later in this post) is that, on the contrary, farmers have made steady gains in their income from agriculture over the last two decades (since 2005) and agricultural income levels have been at their highest in the past three years, despite higher input costs.

Let us now turn to look at the evidence. I focus initially on the EU level, but individual Member States are quite heterogeneous and so are income developments. Given that France is the largest agricultural producer in the EU and the strength of farmer protests in France, I look at France particularly as a case study. Also here, the underlying trends are clearly visible. Finally, even looking at income developments within a country can conceal differences for different farming systems, for different size groups of farms, and for individual farms depending on their dependence on debt, whether they farm their own or rented land, and so on. Still, looking at the macro level is a sensible place to start.

Farm income or the income of farm households is a broader concept than agricultural income as it will also include off-farm income. In this post we are only concerned with agricultural income.

Eurostat income indicators

Eurostat calculates three agricultural income indicators (governed by Regulation 138/2004 on the economic accounts for agriculture, as amended) which provide a good starting point for a macro analysis. They are:

Indicator A: Index of the real income of factors in agriculture per annual work unit (AWU). This corresponds to the factor income available to remunerate all labour, land and capital used in the agricultural industry (in technical terms, net value added at factor cost) divided by the total number of Annual Work Units.

Indicator B: Index of real net entrepreneurial income per unpaid annual work unit (also referred to as family farm income per family work unit, FWU). This indicator is most useful when agriculture is organised in the form of family farms as sole proprietorships. When agriculture is organised in the form of conventional corporate structures which generate entrepreneurial income (profit) exclusively with paid labour, it overestimates income in comparison with the notion of individual income. According to Eurostat, this indicator is most useful in showing trends rather than income levels.

Indicator C: Net entrepreneurial income in agriculture. This indicator represents the aggregate entrepreneurial income for the agricultural industry as a whole. It is the numerator for Indicator B.

All three indicators are presented in real terms, where nominal values have been deflated by the implicit GDP deflator. In the following chart, I also make use of a fourth indicator, namely, real factor income generated in the agricultural industry as a whole (that is, the numerator of Indicator A).

Agricultural income trends at EU level

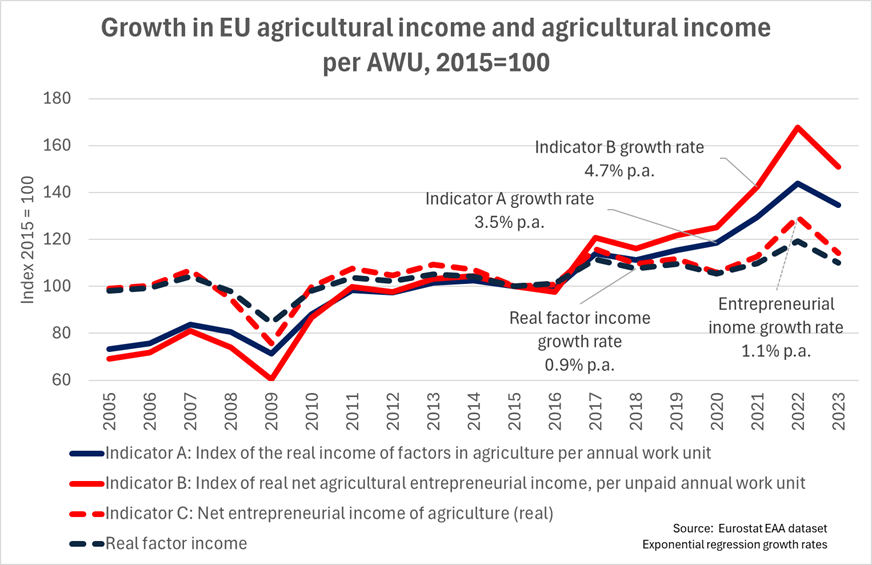

The following chart Figure 1 shows the trend in these four indicators over the period 2005-2023 for the EU as a whole. For comparisons, annual exponential growth rates are also shown.

Look first at the growth over time in aggregate agricultural income, shown by the dotted lines. There is little difference in overall growth rates between total factor income and total entrepreneurial income (0.9% p.a. and 1.1% p.a., respectively). Entrepreneurial income is more sensitive to year-on-year fluctuations because it is a residual after relatively fixed wages to salaried employees and rents for land rented are paid. Looking at the change between the end years, total factor income and total entrepreneurial income have increased only modestly, by 12% and by 15%, respectively, between 2005-2023.

When these aggregate income indicators are divided by the respective number of AWUs or FWUs, we observe a much more significant increase over time. The growth rate for Indicator A is 3.5% p.a. and for Indicator B 4.7% p.a. These growth rates mean that real agricultural income per AWU has increased by 84% over the period 2005-2023, while indicator B shows that the real income per family worker has more than doubled, increasing by 119%.

It is important to look at income levels during the past three years 2021-2023 (keeping in mind that the graph shows real income and thus already takes account of higher inflation during this period). The graph shows that agricultural incomes have never been higher than in those three years. True, incomes fell in 2023 from the record level they reached in 2022, but agricultural income last year was still at the second highest level recorded for the EU.

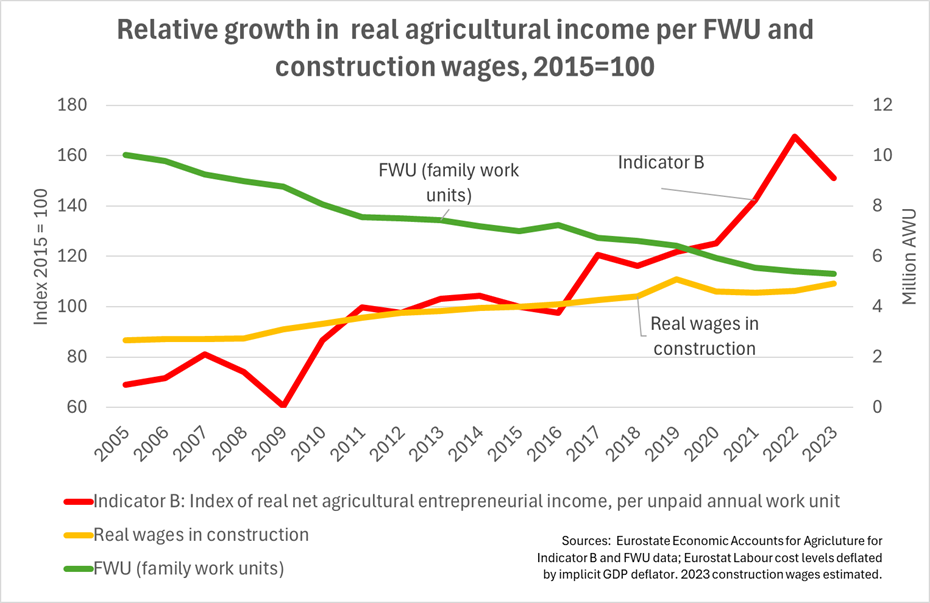

The second chart Figure 2 shows Indicator B both in the context of the total number of Family Work Units (FWU) and the growth in real wages in the construction industry. I use the construction industry as the comparator for agricultural income comparisons, to better reflect education and skill levels among farmers. Because the graph illustrates only the growth in construction wages over time and not the absolute level, and because construction earnings closely follow the growth in average nonfarm earnings, we would have the same picture if I had used average earnings instead (data reasons also play a role as the time series for construction wages is longer than for all wages and salaries in the Eurostat database).

Over the 2005-2023 period, total FWU in the EU has fallen from 10.0 million to 5.3 million FWU, almost a halving of the family labour force in agriculture or a fall of 47%. The increase in entrepreneurial income contributed 18 percentage points to the overall 119% increase in entrepreneurial income per FWU, while the decline in the number of FWUs contributed the remaining 82 percentage points. The decline in the workforce has been the dominant driver behind the increase in agricultural income per worker.

The chart also compares the growth in entrepreneurial income per FWU with the growth in construction wages over this period. Over the whole period, agricultural income per FWU has grown faster than nonfarm wages represented here by the construction sector. Construction wages (and also average wages and salaries) grew steadily over the period until the COVID pandemic in 2020 and have stagnated since then, which in itself is a cause of unrest.

What is worth highlighting is that not only did agricultural incomes continue to increase but even accelerated during this period, despite the COVID lockdowns which continued into 2021 and high input costs in 2022 and 2023 following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

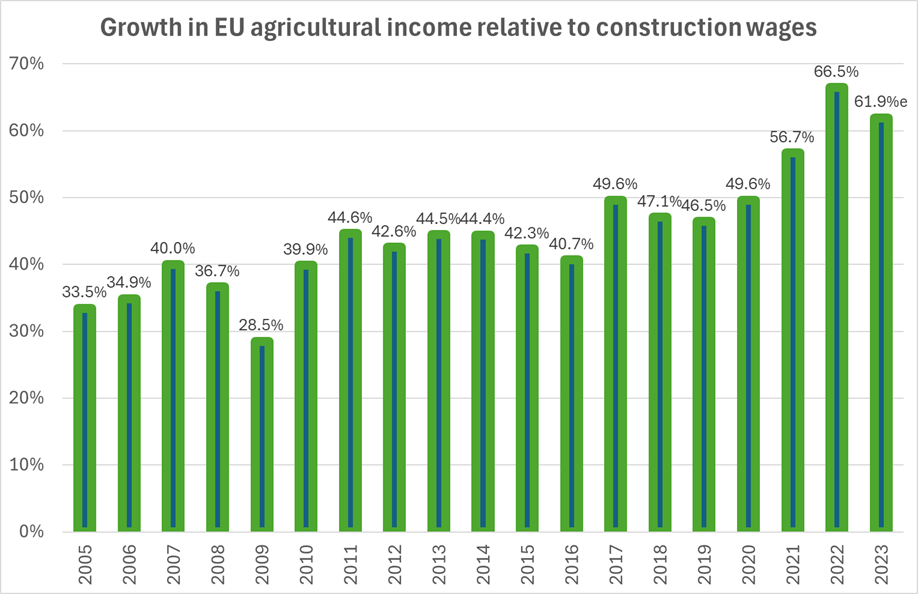

The relative growth in agricultural income and income in the nonfarm sector is shown more clearly in the following chart Figure 3, which is the one I shared on X and LinkedIn. Recall that entrepreneurial income is the return to the family-owned factors of production, mainly labour but also land and own capital. It is thus a partial indicator of labour productivity. Seen in that light, what the figure shows is that (a) for the EU as a whole, labour productivity in agriculture and thus agricultural income has been steadily increasing relative to the nonfarm sector, but (b) there still remains a considerable productivity gap, and there is still a good way to go before there is close to an equilibrium.

Sources: Agricultural income is the ratio of entrepreneurial income in agriculture to family labour work units FWUs in each year, Eurostat, Economic Accounts for Agriculture. Construction wages from Eurostat, Labour cost levels database. Data available at 4-yearly intervals 2004-2020 with linear interpolation for missing years. 2023 data is an estimate taking 2022 wage level and increasing by 2.7%.

Construction wages rather than average wages and salaries are chosen for comparison to reflect more similar personal characteristics, notably education. Comparison with average wages and salaries shows the same trend but with a larger absolute difference.

The French case

A potential problem in examining agricultural income trends using EU-level data is that the numerator (aggregate farm income, whether defined as factor income or entrepreneurial income) will reflect trends in those Member States that contribute most to this variable (just four countries in Western Europe France, Spain, Italy and Germany together account for more than 60% of EU factor income in agriculture), while the trends in the labour force in the denominator will mainly reflect trends in those Member States with the highest shares in the agricultural labour force (mainly in Central Europe). So the EU picture may not be a good description for any individual country. We examine here the case of France as the principal agricultural producer in the EU and one which has experienced vociferous protests in recent months.

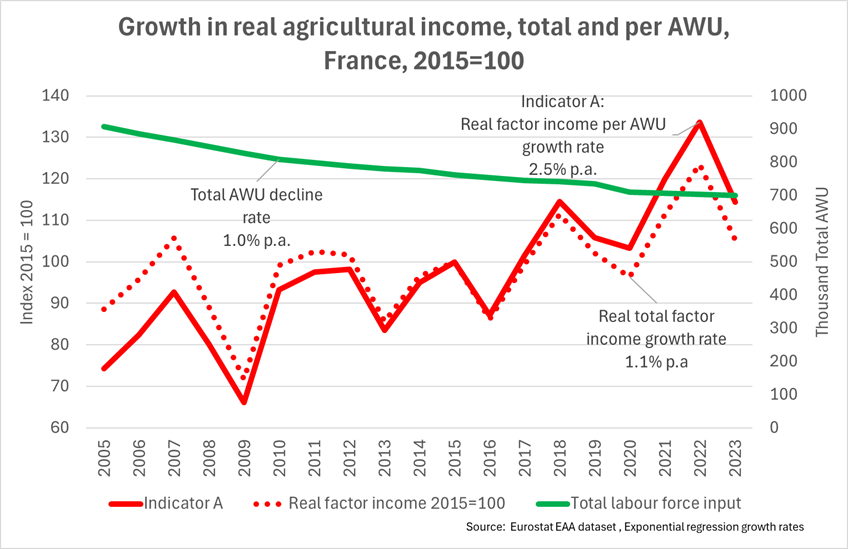

Before presenting the figures we need to note one peculiarity in the French case. In France, many family farms are organised in collective structures, either GAECs (groupement agricole d’exploitation en commun) or EARLs (exploitation agricole à responsabilité limitée). Even if these collective structures mainly employ family labour, these persons are returned as salaried employees in Eurostat statistics. In 2023, around 42% of AWUs in France were reported as salaried workers, which is way above the proportion of non-family salaried workers. However, Eurostat treats the labour income of the shareholders in these ‘specific’ agricultural companies as part of entrepreneurial income even though they are considered as salaried workers. Thus, in the case of France, it does not make sense to calculate agricultural income as the ratio of entrepreneurial income to Family Work Units. Instead, we look at agricultural incomes in France using Indicator A which relates factor income in agriculture to total AWUs. The results are shown in the following chart Figure 4.

As expected, the growth in real agricultural income per AWU in France as measured by Indicator A is rather less impressive than for the EU, with annual average growth of 2.5% p.a. compared to 4.7% p.a. for the EU average. Specifically, the 2023 value was 54% above the 2005 value compared to an increase of 84% for the EU. Real aggregate factor income grew by around 19% over this period, ahead of the 12% growth in real factor income and the 15% growth in entrepreneurial income at EU level.

The main reason for the slower growth in individual agricultural incomes in France was thus the slower reduction in the labour force – a reduction of 23% in AWU in France compared to 47% for the EU (note that the reduction in France was concentrated among workers reported as non-salaried while the number of salaried workers in AWU even slightly increased (by 5%).

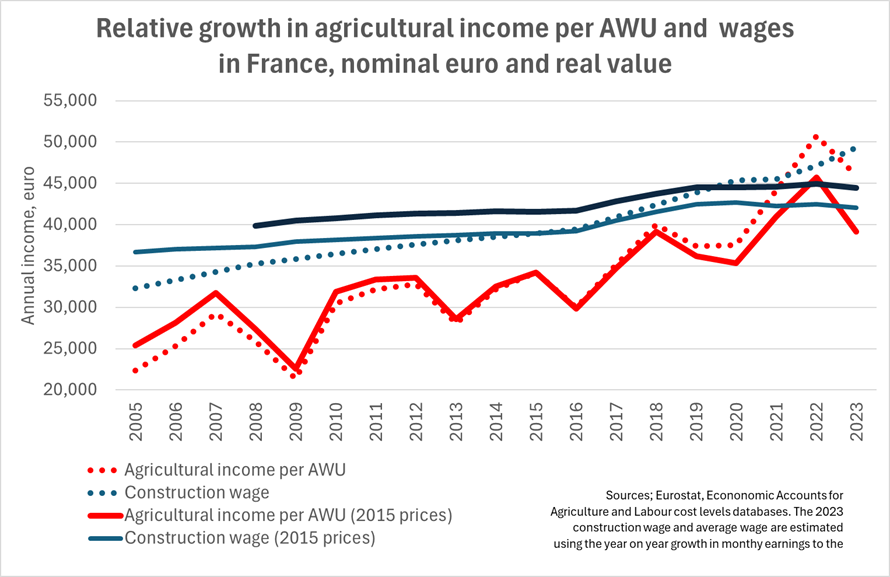

The growth in agricultural and nonfarm incomes in France is compared in nominal and real terms for the period 2005-2023 in Figure 5. Nominal growth is shown by the dotted lines, and real growth by the solid lines. For this chart I have plotted the values in euro rather than as index numbers as I did previously for the EU. I have also included average wages and salaries as well as construction wages to show the very similar trends, with average wages and salaries about 6% above construction wages throughout the period.

In nominal terms, construction wages in France were 44% higher than agricultural incomes in 2005. In 2023, the gap had closed to 8%. The trends are of course similar in real terms though the percentage changes are slightly different.

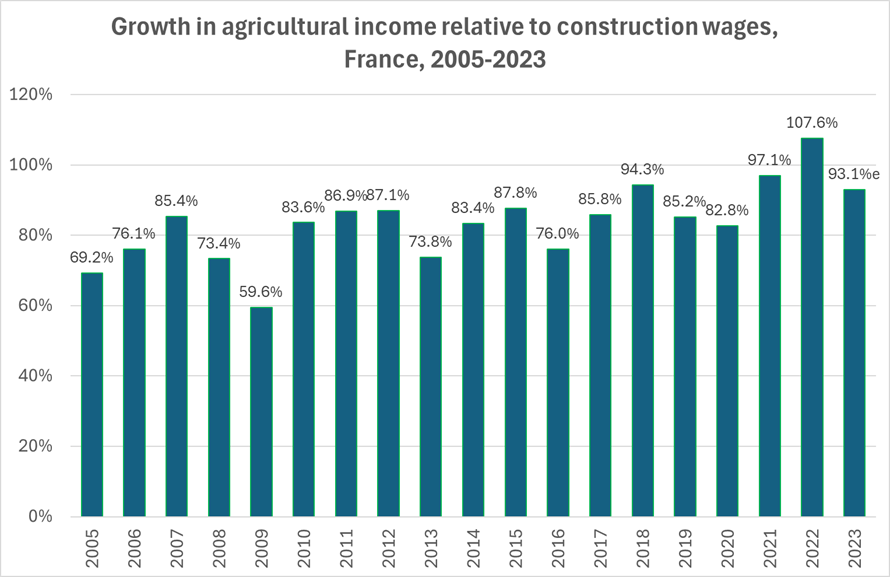

The relative growth in agricultural relative to nonfarm incomes is shown more explicitly in Figure 6. While there is considerable volatility from year to year, the catching up process remains evident although not as pronounced as for the EU case. In particular, the relative agricultural income of French farmers in the past three years has been particularly favourable with the ‘parity ratio’ above 90% in each of the three years, which has only occurred once before in 2018.

Conclusions

If we look at income levels alone, it is hard to understand why income should be a trigger factor for protests just now.

There are several caveats to that conclusion. The first is that what we have evidence for is historical income developments, while farmers may be concerned more about future income prospects. In the short-term, price, income and weather prospects for 2024 are highly uncertain, reflecting uncertainties around global and EU economic growth and geo-political tensions. In the medium-term, the impact of stricter environmental regulations and greater opening to trade may underpin fears that incomes may come under greater pressure in the future.

A second caveat is that, even at Member State level, we are dealing with averages. Particular sectors that have been adversely affected by either price declines or yield losses due to weather may be hidden behind better-than-average performance elsewhere. As is the nature of protests, those who experience losses make the most noise, while those who have had a comfortable year stay at home.

A third caveat is that, even if farmers’ take-home pay from their agricultural activity has been increasing, they may experience greater stress in earning that income. This may reflect some of the other factors mentioned at the outset of this post, such as the need to deal with increasing regulation or the impact of hostile criticism on self-esteem, or that on family-run farms with increasing difficulties to access labour farmers are working harder to keep up.

A final caveat is that the main driver of growth in agricultural incomes comes from a reduction in the number of farmers rather than an increase in the aggregate income available. Even if agricultural income per farmer is increasing, there are fewer farmers. The consolidation of farms has been the most significant factor behind the steady growth in agricultural incomes relative to nonfarm incomes documented in this post. While there is no real evidence that the pace of consolidation has increased in recent years, particular rural regions may be close to a ‘tipping point’ where further reductions in farm numbers have more dramatic impacts on rural communities.

We can certainly ask whether this is a desirable trend and whether there may be other ways to ensure growth in agricultural incomes in the future. This will be the topic for a further post. But we must avoid wishful thinking. The main competition that farmers face is not especially cheaper imports as a result of free trade agreements. It is the steady growth in labour productivity in the nonfarm sector that drives up the incomes against which farmers must compete. Whatever proposals are made to increase farm incomes must demonstrate not only how they will close the income gap that currently exists, but also maintain parity as nonfarm incomes continue to increase in the years ahead.

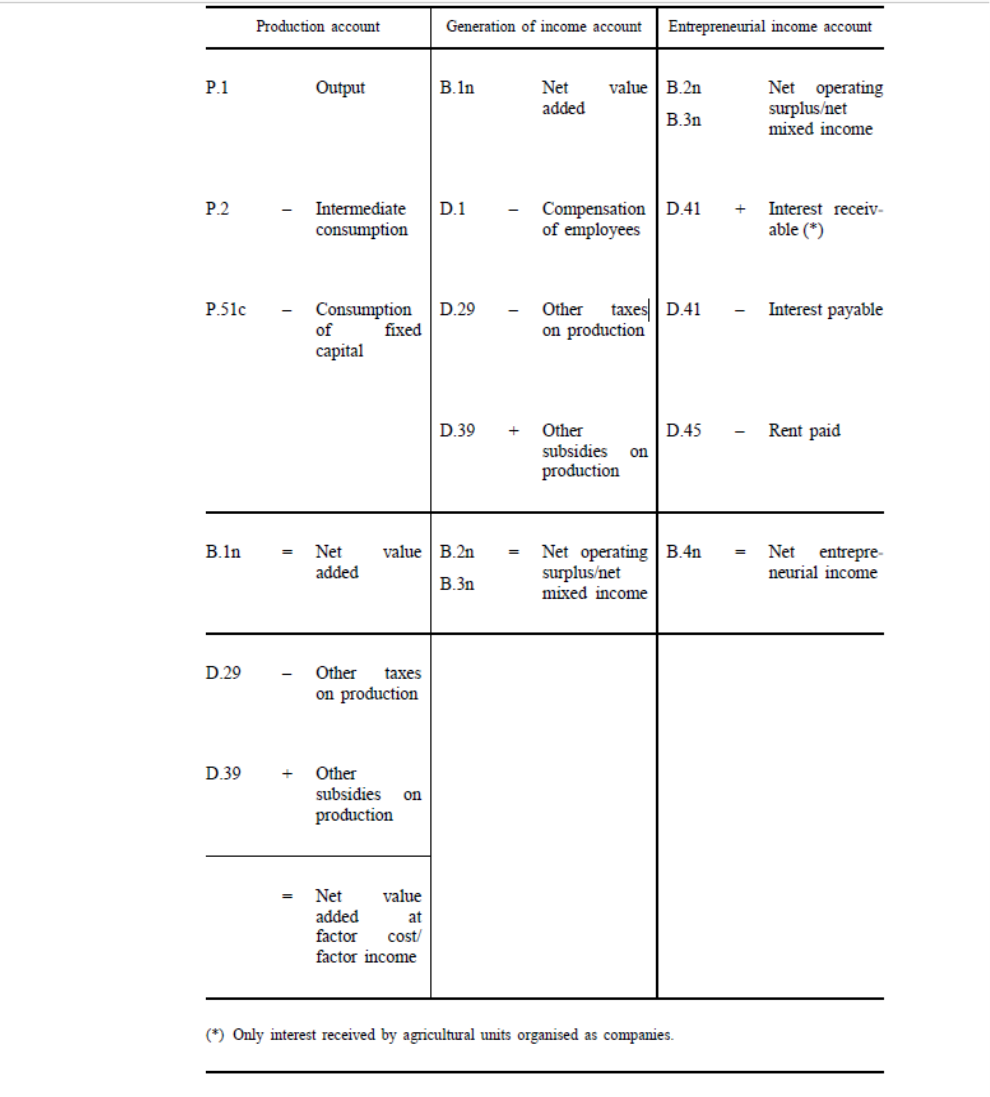

Annex on income concepts in the Eurostat Economic Accounts for Agriculture

Some readers might find it helpful to be reminded of the components that make up the different agricultural income concepts used in this post. There are three balancing items which can be used as an income aggregate for the agricultural industry: net value added, net operating surplus (net mixed income) and net entrepreneurial income. The relationship between these items is set out in the following diagram.

5 Feb 2024. Some minor textual changes made for clarity.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Picture credit: SurveyHacks.

As always, interesting article. punctual compared to the events of protest of farmers in these weeks.

We hope to have you in Italy (I’m a colleague of Andrea Povellato of http://www.crea.gov.it – rica.crea.gov.it)

Thanks, Antonio, appreciated.