2025 marked a decisive break in relations between the United States and Europe. From U.S. Vice-President Vance’s speech in February at the Munich Security Conference to the publication of the U.S. National Security Strategy at year’s end, Washington has framed the European Union not as a strategic partner but as an obstacle to U.S. objectives. This shift was illustrated throughout the year by escalating trade actions, growing divergence over Ukraine, and threats against tech regulation. By the end of the year, the EU had accepted an unequal trade deal with the United States, undermining its long-standing self-image as a ‘soft power’.

The EU is also addressing mounting tensions with China, a consequence of the widening Chinese trade surplus, its willingness to assert its control over rare earths and magnets, and a series of tariff actions affecting particularly agri-food products. Trade relations with Russia have been subject to restrictions since the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014 and subsequent sanctions following its invasion of eastern Ukraine. Although EU sanctions do not prevent the export of food to Russia, Russia itself has imposed an import ban on most EU (and other sanctioning countries) food products, including meat, dairy, fish, fruit, vegetables, and cereals since 2014.

The question now is how the EU should respond to this altered geopolitical context.

This post examines the implications of the abrupt change in United States attitudes towards the EU in 2025 with a particular focus on agri-food trade. The deterioration in relations with the U.S., the normalisation of tariff escalation, and the growing role of security considerations in trade policy, have created a more uncertain and politicised environment for EU agri-food exports. Early evidence suggests that U.S. tariff measures introduced during the year have already had measurable negative effects for EU exporters. Agri-food policy can therefore no longer be considered in isolation from wider debates about economic security and geopolitical alignment. The EU now faces a set of difficult choices: how far to prioritise market openness over resilience, whether and how to respond to trade pressure, and how to reconcile agricultural, trade, and security objectives in a more fragmented global economy.

The new relationship with the U.S.

The tone was set in February 2025 with the speech by U.S. Vice-President Vance at the Munich Security Conference in which he ignored any threat from Russia and argued that the main dangers to Europe’s security were unregulated migration, the exclusion of far-right political groups, and restrictions on free speech.

On 2 April 2025, President Trump ignored U.S. commitments under the WTO and announced a range of bilateral reciprocal tariffs on its trading partners, including a 20% tariff on EU imports on top of existing tariffs. This came in addition to previously reinstated 25% tariffs on steel and aluminium implemented on 12 March 2025. On 9 April President Trump announced a pause on the full implementation of these tariffs for 90 days to allow negotiations with third countries to take place. The tariff rate on EU imports was reduced from 20% to the 10% baseline. In response to the pause, the EU Commission announced that it would suspend the implementation of counter-measures planned against the U.S. steel and aluminium tariffs.

Trump subsequently expressed impatience with the pace of the U.S.-EU negotiations, threatening on social media on raise tariffs on EU imports to 50% on 23 May. He subsequently raised steel and aluminium tariffs from 25% to 50% effective 4 June 2025. Then, on 12 July 2025, President Trump announced new 30% tariffs, in addition to existing tariffs, on EU goods to take effect 1 August 2025. In his extraordinary letter to President von der Leyen, he also threatening to increase this tariff rate by the amount of any tariff imposed by the EU if it chose to retaliate.

Then on 27 July, Trump and von der Leyen met at Trump’s golf course in Turnberry, Scotland. The two parties announced a political agreement to reduce U.S. tariffs to a flat-rate 15% tariff on all EU imports with just few exceptions such as steel and aluminium (the Turnberry agreement). The agreement also reduced the previous 27.5% tariff imposed on imports of EU cars and parts under Section 232 to 15%, while exempting imports of aircraft and aircraft parts as well as generic pharmaceuticals and their ingredients and chemical precursors from additional tariffs. Further, the U.S. committed to apply a tariff not exceeding 15% to imports from the EU of pharmaceuticals, semiconductors and lumber that are subject to Section 232 tariffs. In return, the EU committed to reducing or eliminating tariffs on a wide range of U.S. industrial and agricultural goods.

The agreement also includes targets for EU private investment in the U.S. ($600 billion in the years to 2028), for EU purchases of U.S. liquified natural gas and nuclear energy products valued at $750 billion, for EU purchases of U.S. AI chips for computing centres for at least €40 billion, and for increased procurement of U.S. defence and military equipment. These commitments were further elaborated in a joint statement on trade and investment (the European Union-United States Framework on an Agreement on Reciprocal, Fair, and Balanced Trade) by the EU and the U.S. in August 2025. At the same time, the EU formally suspended its previously announced rebalancing counter-tariffs.

The tensions between the EU and the U.S. have not only been about trade but also about security and defence strategy and Ukraine. The U.S. explicitly wishes to reduce its commitment to Europe’s security as it seeks to prioritise its resources and attention on other parts of the world. With some justification, it has demanded that Europe step up and take on greater responsibility for its own defence. At the June NATO summit in The Hague, 23 Member States also NATO allies agreed to increase defence spending to a 5% of GDP target. The European Commission has responded with its White Paper on defence Readiness 2030 proposal which foresees a significant increase in defence spending of up to €800 billion over the coming years, unlocked by giving Member States greater budgetary space within the Stability and Growth Pact as well as providing up to €150 billion in loans to Member States for jointly procuring defence equipment.

However, tensions persist around different perceptions of the threat that Russia poses and how to bring an end to the war in Ukraine. The Trump administration seeks to re-open relations with Russia with a view to economic normalisation, with those close to the administration seeing significant economic opportunities from closer cooperation. Within this framework, Ukraine is primarily viewed as an obstacle to a broader geopolitical accommodation with Russia, rather than being the central subject of any peace deal. This explains U.S. pressure on Ukraine throughout 2025 for rapid negotiations to agree to conditions to end the war, including acceptance of territorial concessions, limits on the size of its armed forces, and the absence of meaningful security guarantees.

The European position sees Russian aggression as a direct and continuing security threat, not only to Ukraine but to the European security order. Any settlement that validates territorial conquest is seen as creating a dangerous precedent for EU border states. The EU position is that Ukraine must be centrally involved in any peace negotiations, and that sustained financial and military support to Ukraine is necessary both for battlefield resilience and for negotiating credibility. The agreement in December 2025 by 24 EU Member States to provide a further €90 billion in financial support to Ukraine is an expression of this view.

At the same time, it is important that the EU continues to support meaningful negotiations to end the war. The American-led mediation efforts in Miami in late December 2025 failed to make a breakthrough. President Macron’s suggestion to open direct contact with the Kremlin, and Putin’s apparent willingness to speak with Macron, although controversial, makes sense in that context.

Finally, another pressure point in U.S.-EU relations is the Trump administration’s expressed desire to annex Greenland and his appointment in December 2025 of a special envoy with the brief to make Greenland a part of the U.S.. The U.S. already has broad powers to station defence forces on the island under the 1951 Greenland Defence Agreement between Denmark and the U.S., though still under Danish sovereignty. Greenlanders (pop. 57,000) have expressed a desire for independence from Denmark, and the Danish Self-Government Act of 2009 explicitly recognises the right of the Greenlandic people to self-determination and future independence. Both the Danish and Greenland governments have demanded respect for their borders in response to American actions.

It is hardly a coincidence that, on the same day as the appointment of the special envoy, the Trump administration suspended leases for five large offshore wind projects that are under construction off the U.S. East Coast over what it called national security concerns. Two of these are owned by Orsted, a Danish company in which 50.1% of the shares are owned by the Danish government. Orsted’s Revolution Wind wind farm, which was 80% complete at the time, had already been subject to a stop-work order for national security reasons by the U.S. government in August 2025 which caused Orsted’s share price to collapse. The limited recovery in its share price after a judge lifted the ban in September was reversed by the latest move, putting further economic pressure on the Danish government. Trump’s desire to annex Greenland mirrors Putin’s desire to annex Ukraine and Xi’s desire to annex Taiwan.

Anyone who was deceived by the chaotic rollout of U.S. trade and security policies over the past year into thinking that these were aberrations or abnormalities will have had their illusions firmly shattered by the publication of the latest U.S. National Security Strategy in early December. After noting that continental Europe’s share of global GDP has been declining, it identifies Europe’s principal challenge as civilisational erasure. This is blamed on the activities of the European Union and other transnational bodies that are alleged to undermine political liberty and sovereignty, migration policies, censorship of free speech, and suppression of political opposition. To reverse these ills, the strategy proposes that America should cultivate resistance to Europe’s current trajectory by encouraging “patriotic European parties” that support the idea of Europe as a group of aligned sovereign nations. The U.S. administration effectively seeks to destroy the European Union and erase its achievements.

U.S. tariffs on EU agri-food exports

This section of the post focuses on the mundane issues of agri-food tariffs, but it is important that we see these within the context of this bigger picture. We start by assessing the tariffs imposed by the U.S., and then examine the concessions made by the EU.

On 2 April 2025 President Trump announced that goods imported from all countries into the U.S. from 5 April 2025 will be subject to a baseline tariff of 10%. The baseline tariff of 10% is in addition to the normal duty rate that previously applied to the import of goods into the U.S.. For selected territories including the EU, higher “reciprocal tariff” rates were announced to apply from 9 April onwards that took the place of the baseline tariff and were also in addition to the normal duty rate.

On 9 April President Trump issued a further Executive Order that suspended the additional reciprocal duties for 90 days (until July 9), on the argument that this would allow negotiations with countries that had signalled a willingness to engage with the United States to conclude. It also confirmed that the baseline additional tariff of 10% (in addition to existing MFN tariffs) would come into effect the following day, April 10. Subsequently, in Executive Order 14266 on 7 July, President Trump extended the period for negotiations before the reciprocal tariffs should kick in to 1 August.

As noted, Commission President von der Leyen and President Trump reached a framework deal on 27 July. The tariff component of this agreement was that the U.S. would apply from 1 August a single, all-inclusive tariff ceiling of 15% for EU goods. This included the MFN rate that was previously stacked on top of additional tariffs that the U.S. had introduced. Where the MFN rate exceeded 15%, this rate continues to apply but without any additional tariff. This agreement was incorporated into the White House Executive Order 14326 of 31 July which also stated that it would come into effect 7 days later. U.S. Customs Guidance confirmed that EU imports were subject to the new tariff regime from 7 August 2025. These tariff rates thus have applied to EU agri-food exports to the U.S. since that date. The continuation of these tariffs depends on the EU implementing its part of the Turnberry agreement, otherwise the tariffs will revert to those originally announced on 2 April.

An obvious question to ask is how the new U.S. tariff regime compares to the previous MFN regime for agri-food products. The U.S. International Trade Commission maintains an archive of the U.S. tariff schedule that allows a comparison with the current schedule post August 2025.

Unfortunately, it is not easy to make an overall comparison. This is partly because tariff rates within a specific product category (e.g. dairy products) can vary widely and would need to be aggregated (either as a simple average or weighted using trade weights) to calculate an average tariff. Also, in some cases, as for certain meat products or wines, MFN tariffs are levied as an absolute amount so the ad valorem percentage tariff varies depending on the customs value of the imported product. This makes a comparison difficult with the standard 15% tariff that now applies.

In general, however, U.S. MFN tariffs on agri-food products are quite low (some selected examples are given in Table 1). There are some products where the tariff charged on EU exports after 10 August has not changed, because the MFN tariff was already 15% or higher. But for many products exporters faced a considerable increase in tariffs in early August. The EU wine industry is particularly affected as it now faces import tariffs of 15% in its largest export market (existing U.S. wine tariffs are particularly complex and are not included in Table 1).

Source: U.S. International Trade Commission, 2025 Harmonised Trade Schedule.

Impact of increased U.S. tariffs on EU exports to the U.S.

A question is what impact has this had on EU exports of agri-food products to the U.S.? Assessing any impact to date is difficult because the latest trade data at the time of writing refer to October, so we have less than three months data to hand since the latest tariffs came into force. Furthermore, the dramatic increase in trade policy uncertainty throughout the year is likely to have influenced the pattern of trade. Exporters may have accelerated deliveries in the early part of the year to avoid additional tariffs, importers may have built up stocks, and this may have influenced the demand for imports from the EU towards the end of the year.

Another factor complicating the analysis is that the U.S. has also imposed higher tariffs on other trading partners. Tariffs make EU food products (butter, pasta, wine) more expensive relative to domestic U.S. production, but how it impacts the competitive position of EU exports relative to other exporters depends also on the tariffs they face .

The impact of tariffs also depends on the extent to which they are passed through to retail prices. Although much economic commentary has assumed that tariffs are fully passed through to U.S. consumers, this is not necessarily the case. There are several intermediaries between the importer and the consumer that may decide to absorb some of the tariff increase in order to maintain sales, while the EU exporter may also be motivated to lower its export price for the same reason. While this strategy may help to maintain the volume of sales, it will also lower export receipts.

Finally, the level of imports is also a function of income developments as well as trade policy. The U.S. economy has remained quite robust in 2025, with GDP growth projected to be around 1.7% to 1.9%. Although inflation has been running at around 3% and there are signs of a weakening labour market, consumer spending especially among higher-income households (supported by resilient stock markets) which are more likely to purchase high-quality EU food imports has remained strong.

The latest DG AGRI Monitoring EU Agri-food Trade publication for October 2025 notes that overall EU agri-food exports have increased by 2% in value terms in the first ten months of 2025 compared to the same period in 2024, while the value of exports to the U.S. fell by 3% between the same periods. However, value changes in trade are heavily influenced by changes in prices (for example, prices for cocoa paste, butter and powder were up by 68% and prices for coffee by 29% between these periods). We should thus be cautious to attribute this slight fall in the value of agri-food exports to the U.S. solely to trade policy alone.

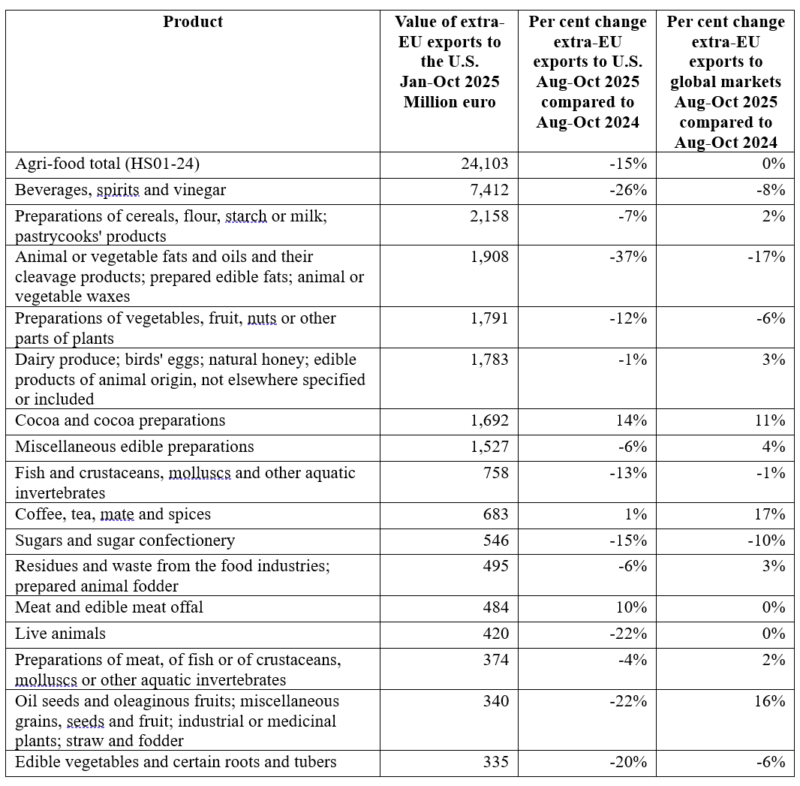

More convincing evidence of the negative impact of the tariff changes is shown in Table 2. This compares the percentage change in the value of exports of agri-food products to the U.S., compared to total extra-EU exports, for the three-month period August-October 2025 after the latest tariff changes took effect, to the same three-month period in the previous year. Overall, exports to the U.S. were down 15% by value when exports worldwide held steady. Furthermore, in almost every product group, either sales to the U.S. fell when they increased worldwide, or they fell by more than the fall in worldwide sales. The only exceptions are cocoa products (chocolate) and meats. Given that consumer demand in the U.S. has been quite strong, this drop in the value of exports is likely due to the tariff changes, although changes in the monthly patterns of trade due to ongoing uncertainty may also have contributed. As noted, the drop in the value of exports could be due to a drop in the volume of sales, or because EU exporters decided to absorb some of the tariff increase by lowering their export prices.

Source: Eurostat Comext.

Implementing the EU concessions

These U.S. tariffs are contingent on the EU implementing its reciprocal commitments. The European Commission submitted a legislative proposal on August 28, 2025, to the Council and the European Parliament to eliminate duties on all U.S. industrial goods and grant preferential treatment to certain U.S. agricultural and seafood products. A second proposal prolongs an elimination of customs duties on certain types of lobster granted in 2020 for a five-year period until 31 July 2025 and expands the scope of this concession to processed lobster.

The draft regulation provides that the applicable customs duties in the Common Customs Tariff on imports of industrial goods originating in the U.S. shall be 0%, variously referred to as an ‘adjustment’, ‘non-activation’ or ‘suspension’ of duties on imports from the U.S. According to the Commission, its proposal would extend duty-free treatment from 66% of total industrial goods imported from the U.S. to 100%.

For seafood and agricultural goods, preferential market access is provided to non-sensitive agricultural products only, where there is a Union interest to facilitate imports. This is done through a partial liberalisation for certain agricultural goods and through tariff quotas. The agricultural products affected and deemed to be non-sensitive include tree nuts, dairy products, fresh and processed fruits and vegetables, processed foods, planting seeds, soybean oil, and pork and bison meat. The Commission estimates this will lead to a loss in customs revenue of €4.9 billion, implying a loss of revenue to the EU budget of €3.6 billion given that Member States retain 25% of collected duties as compensation for collection costs.

Specifically, liberalised goods are divided between three Annexes. Annex 1 goods are fully liberalised with a 0% tariff. In addition to industrial goods, this list also includes some vegetables (HS07), fruits (HS08), plant seeds (HS10 and HS12), and vegetable and fruit preparations (HS20). Annex II lists products where only the ad valorem element of the tariff is removed (certain vegetables, fruits and grape juice). Annex III lists seafood and agricultural products for which tariff rate quotas are opened. These include pigmeat (25,000t quota at 0% tariff), bison meat (3,000t at 0% tariff), fresh dairy products and dairy spreads (10,000t at 0% tariff), cheeses (10,000t at 0% tariff), nuts (500,000t at 0% tariff), soybean oil (400,000t at 0% tariff), animal feed preparations (40,000t at 0% tariff), cocoa powder and chocolate (40,000t at a preferential tariff rate), various food preparations (300,000t at preferential rates), and flavoured waters and non-alcoholic beer (20,000t at 0% tariff).

The Commission proposal also provides for the suspension of these concessions under certain conditions. This includes a standard safeguard clause where concessions can be suspended if they result in the import of goods in such increased quantities as to cause or threaten to cause serious injury to the domestic industry of the Union.

In addition, the draft legislation provides that concessions can be suspended in whole or in part “(a) where the United States fails to implement the Joint Statement or otherwise undermines the objectives pursued by the Joint Statement, or undermines access of Union economic operators to the United States market, or otherwise disrupts the trade and investment relationship between the Union and the United States; (b) where there are sufficient indications that the United States will act in the manner referred to in point (a) in the future; or (d) where a change of objective circumstances has occurred with regard to those existing at the time the Joint Statement was issued.”This gives the Commission the power to respond should the U.S. enact additional punitive tariffs or measures against EU imports although it does not mandate a response.

The Council adopted its negotiating mandate on the draft proposal in November 2025. The Council strengthened the procedures around the initiation of safeguard measures. It also added a provision on monitoring the economic effects in the Union of the trade liberalisation measures and a review clause.

The rapporteur of the Committee on International Trade in the European Parliament Bernard Lange published his draft report in October 2025. One of his proposed amendments specifies that any new tariff as a result of any ongoing or future U.S. Section 232 investigation or based on any other legal basis, entering into force after the signature of the Joint Statement, and that exceeds the all-inclusive 15 % tariff ceiling, should lead to the suspension of the application of the EU concessions. He also pushes back against any U.S. attempt to influence EU regulations by proposing that the EU concessions should be suspended in the event of any attempts by the United States to influence, through the threat of additional tariffs or of other restrictive commercial measures, Union legislative processes or the enforcement of Union legislation.

He proposes that any increase in the volume of imports by more than 10% should be deemed evidence of serious injury, or threat of serious injury, to Union industry. Regarding the provision (d) regarding a change in objective circumstances, the rapporteur would specify that this also includes changes affecting the essential security interests of the Union or of its Member States. He also proposes that the 0% tariff concession on U.S. steel and aluminium imports should be delayed until sustainable and mutually acceptable arrangements on trade in these and their derivative products are agreed with the U.S. He is clear that the Joint Understanding breaches long-standing WTO rules regarding Most Favoured Nation treatment and expresses the aspiration that it should lead to a comprehensive trade agreement in line with WTO rules.

The Parliament has pencilled in the 9 February 2026 as the indicative plenary sitting date to agree its first reading position, after which it would enter trilogue negotiations with the Council. The final shape of the EU commitments may well differ from what the Americans thought they had agreed in the Turnberry agreement and Joint Statement earlier in the year.

The U.S.-EU trade deal rests on shaky foundations

Although the Joint Statement issued in August 2025 refers to a framework for an agreement on reciprocal, fair and balanced trade, from an EU perspective the commitments are hardly fair and balanced. EU exports now face higher tariffs to enter the U.S. market, while the EU proposes to fully liberalise U.S. exports and to extend preferential access for certain seafood and agri-food products. The Commission argument is that the deal reached with the U.S. is more favourable than for other U.S. trading partners, and that it provides stability for transatlantic trade compared with the dangers of a spiralling trade war in the absence of an agreement.

However, whether the U.S.-EU trade relationship is now more stable or not is open to question. The Turnberry agreement rests on shaky foundations. The open hostility to the EU in the National Security Strategy does not give the sense that the U.S. wishes to be a reliable trade partner, and it has many opportunities to scupper the deal.

Already in November, Jamieson Greer, the U.S. Trade Representative, was warning that trade remains a ‘flashpoint’ in relations with Washington. Americans are clearly impatient with the slow pace of implementation of the EU’s commitments under the Joint Statement, which reflects the deliberative nature of the EU legislative process. The European Parliament will not vote on its position until February next year. It may also add amendments, such as its proposal to delay tariff cuts on steel and aluminium until the U.S. reduces its 50% tariffs on these metals, which will further complicate negotiations.

Meanwhile, the U.S. continues to widen the coverage of its tariff policy. Though not specifically directed against the EU, on 19 August 2025 it added some 407 product categories to the Section 232 steel and aluminium tariffs of 50% as well as opening new Section 232 investigations. This requires companies exporting these products to the U.S. to quantify the steel and aluminium content of their products and to pay the higher duties on that content, which is both complex and costly.

The most likely way in which the agreement will implode is around the issue of regulation of company practices. The U.S. has exerted sustained pressure on the EU’s sustainability agenda, openly criticising the extraterritorial reach of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive and Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, as well as the Deforestation Directive and CBAM Regulation. In the Joint Statement in August 2025, the EU committed to reviewing these directives to minimise their impact on U.S. companies. Although also driven by pressure from EU companies and Member States, the EU co-legislators in November and December agreed to considerably water down these legislative acts, both in scope and obligations.

Regulation of tech companies under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, Digital Markets Act, the Digital Services Act, the AI Act and the forthcoming Digital Fairness Act remains a red-letter issue for the U.S. Senior U.S. officials have publicly criticised this legislation, arguing that it unduly burdens U.S. tech firms and infringes on free speech norms. When the EU earlier this month imposed a €120 million fine on Elon Musk’s X, American commentators immediately framed this as an attack on free speech, although the specific offences for which X was fined had nothing to do with free speech.

In a subsequent post on X on December 16, the U.S. Trade Representative listed a set of EU service providers that export to the U.S., including Accenture, Amadeus, Capgemini, DHL, Mistral, Publicis, SAP, Siemens, and Spotify, and threatened to impose fees or restrictions on these services if the EU continues to “restrict, limit, and deter the competitiveness of U.S. service providers through discriminatory means”. The EU’s competition chief Teresa Ribera subsequently defended the EU’s right to set regulatory standards. Then on Christmas Eve, the U.S. imposed visa bans on five individuals, including former EU Commissioner Thierry Breton, associated with regulation of the digital sphere and whom it has accused of working to censor freedom of speech. This issue is likely to escalate further in the New Year.

Conclusions

This post has described the unprecedented changes in the U.S.-EU relationship around trade in 2025. The question remains, how should the EU have responded, and how should it respond if, as I expect, the relationship further breaks down in 2026?

One group, whom I dub the ‘trade warriors’, point correctly to the very unbalanced trade outcome as reflected in the Joint Statement. They argue that the EU should have immediately responded with counter-measures. John Clarke, the former DG AGRI trade negotiator, wrote that “The EU should have been tougher much earlier, as China was. As Canada is”. Jean-Luc Demarty, a former Director-General of DG TRADE, advocated that the “EU should immediately apply reciprocal tariffs to the United States to the tune of €100 billion and trigger the anti-coercion instrument with regard to American digital and financial services, without penalising our business” (my translation). Professor Alberto Alemanno described the Turnberry deal as “an ideological and moral capitulation”. He bemoaned the fact that “By giving in to Trump’s demands, the EU missed a rare opportunity to demonstrate that large markets cannot be bullied.”

However, trade policy should be strategic, and not based on emotions. The purpose of retaliation should be to deter the aggressive use of trade policy by one’s partner by raising the cost of that policy. Whether retaliation is a sensible strategy or not depends on whether retaliation is likely to be effective as a deterrent. It also depends on the balance of costs, as retaliation also has a cost to the retaliating country (by raising the cost of possibly essential inputs to its own industry or goods to its consumers).

The effectiveness of retaliation and the balance of costs, in turn, depends on the extent of trade leverage that each partner can exert on the other. China could threaten effective retaliation because it is, for the moment, the monopoly supplier of rare earths and permanent magnets which are essential components for electric vehicles, wind turbines, medical equipment and defence industries. Canada attempted retaliation by announcing its own reciprocal tariffs but subsequently backed down on most of its counter-tariffs and opted to enter negotiations.

The EU’s scope to inflict pain on the U.S. economy is limited. In part, this is because of the very imbalance in trade in goods about which Trump complains. In 2024, the EU exported goods worth €532 billion compared to U.S. exports to the EU worth €333 billion. On this simple measure, the EU has more to lose from a tit-for-tat escalation. Further, the U.S takes 22% of extra-EU exports while the EU accounts for 18% of U.S. goods exports. But even these figures overestimate the trade leverage of the EU because it is a much more export-dependent economy than the U.S. – exports are equivalent to 16% of EU GDP but only 8% of U.S. GDP. Adding to this unfavourable starting point that Trump has an ideological commitment to tariffs that goes well beyond a rational cost-benefit calculation further underlines that retaliation was unlikely to have a deterrent effect. At the same time, other commentators have made the cross-linkage between tariffs and continuation of necessary elements of U.S. military support for Ukraine. Unpalatable as the decision may have been, the Commission made the right call to suspend counter-measures and continue with negotiations.

But this does not mean we should accept the status quo. The necessary response is to reduce our dependencies to allow more room for manoeuvre in any future stand-off, recognising that this is easier said than done. The EU is already making a start to increase Europe’s independent ability to defend itself. Similar steps need to be taken to increase our economic security. How exactly that should be pursued remains contested and controversial, including in the agri-food domain. But that is the important debate that needs to be taken up as we enter the new year of 2026.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit: Liberty headshot by sarowen, licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.