The European Council meets this Thursday in the hope that it will agree on a package of measures that will satisfy the UK’s demand for a renegotiation of its relationship with the EU. The details of the package and the main stumbling blocks are spelled out in the Council President Donald Tusk’s invitation to leaders to the Council meeting. The mood music leading up to the summit meeting is constantly changing. Whether this is a careful choreography to persuade voters back home that what will be achieved is a significant deal, or whether the continuing objections will derail a deal will be clearer by the end of this week. If a deal is reached, there is heavy speculation that the referendum date itself could be 23 June.

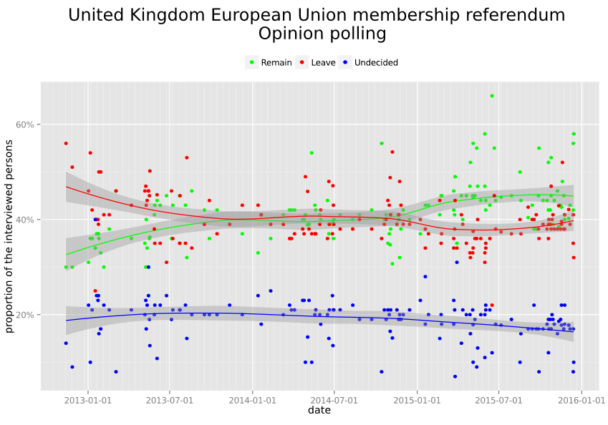

UK opinion as captured by opinion polling is shown in the chart below. If we mark the official start of the Brexit debate as the date of the UK Prime Minister’s famous Bloomberg speech on 23 January 2013 (still one of the best arguments in favour of the European Union that I have read), those in favour of Leaving were reportedly ahead at that stage. Those wanting to Stay (now called Bremainers) caught up in the course of 2013 and for most of 2014 the two sides were level pegging.

Then at the beginning of 2015 the Bremainers pulled ahead, but in recent weeks the gap has been narrowing again. It should be noted that a larger majority says that it would support the Remain option if the Prime Minister achieved a satisfactory settlement in Brussels on which he campaigned to stay in. Clearly, opinion remains volatile and there could easily be significant swings in either direction during a campaign, particularly given the fickle nature of referendum voting.

Source: Wikipedia article on UK opinion polling on EU referendum, with thanks to user T.Seppelt who has created and updates this graph, CC BY-SA 4.0.

A steady flow of reports

In recent weeks there has been a steady flow of reports evaluating the possible consequences for UK farming of withdrawal from the EU. It is impossible to make any sensible evaluation, because no one knows the agricultural, trade, budgetary and regulatory policies that would be put in place if the UK did vote to leave in its referendum. However, these reports are useful in raising the key issues that would need to be addressed. These documents include:

- The NFU’s UK Farming’s Relationship with the EU

- A report for the Yorkshire Agricultural Society led by Wyn Grant and including Alan Swinbank entitled The Implications of ‘Brexit’ for UK Agriculture

- Agricultural Implications of Brexit prepared for the Worshipful Company of Farmers (one of the Livery Companies of the City of London) by Allan Buckwell

In an address to the AHDB Outlook conference in London last week, I gave an overview of some of the main issues raised in these reports (my presentation can be downloaded here). This built on an earlier working paper I wrote in which I considered some possible implications of Brexit for the Irish agri-food sector.

There is little doubt that, in purely agricultural terms, Ireland will be the country most severely affected by a UK withdrawal from the EU given the close trading relationships between the two countries and the expectation that the current easy flow of goods and services across the Irish Sea would no longer be possible if Brexit were to occur. In particular, Brexit would most likely mean the reintroduction of an economic border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, as we remember it from the days prior to the introduction of the single market in 1992.

Currently, the Northern Ireland Affairs Committee of the House of Commons is conducting an inquiry into issues affecting Northern Ireland arising from the forthcoming referendum on EU membership. Opinions on Brexit in this Committee, as in the UK Parliament generally, are divided. In his evidence to the Committee, Tom Arnold, Director-General of the Institute for International and European Affairs in Dublin, focused on the implications for Northern Ireland agriculture (here is a videocast of this evidence). Two issues arising from the questioning are worth examining in more detail.

Does the UK contribution go to fund EU farmers?

In one line of questioning, Ian Paisley MP wanted to establish the point that the reason that the Republic of Ireland was worried about the negative effects of a possible British exit on its agri-food sector was because the large UK net contribution to the EU budget helped to fund the generous EU transfers to Irish farmers. It is indeed a common misconception among supporters of a Brexit that most of the UK contribution to the EU budget continues to go to support the Common Agricultural Policy. Like the myth that a Brexit would lead to lower food prices in the UK (a myth I dispel in my AHDB presentation), this is based on outdated impressions and data from long ago.

Looking at the up-to-date figures on UK flows to and from the EU budget for 2014, a different picture emerges. Applying the UK share of 14.1% (before the rebate which is applied to reduce the UK net contribution to the EU budget) in financing overall EU expenditure to the CAP budget, then the difference between what the UK received from the CAP in 2014 (€3.88 billion) and what it contributed to the CAP budget (€7.63 billion) was €3.75 billion. Reducing this by the UK rebate which reimburses the UK by 66 per cent of the difference between its contribution and what it receives back from the budget means that the net contribution of the UK to the CAP budget in 2014 once the rebate is taken into account was €1.27 billion. This is in the context of a CAP budget of around €54 billion in 2014.

Relatively little (around 18 per cent) of the UK net contribution now goes to supporting farmers in other EU countries. The UK’s net contribution to the overall EU budget is mainly due to its contribution to transfers to the new member states and to items like the EU’s development aid budget, rather than its funding of farmers in other member states. If the UK were to withdraw from the EU and retain its net contribution, the main losers would be the countries of central and eastern Europe whose membership of the EU the UK so strongly supported. This point also needs to be borne in mind by these governments when deciding their attitude to the renegotiation package to be put to the European Council later this week. (Update 24 February 2016: These two paragraphs have been revised to correct a calculation error in the original post, while the UK share has been calculated using its financing share of the total EU budget rather than its share of the GNI resource).

Can the status quo in trade be maintained if the UK leaves?

A second line of argument put forward at the Committee in questions both from Ian Paisley MP and Kate Hoey MP showed a startling naivity in understanding the consequences of a UK exit. Both MPs made the point that there were no voices either in the UK or in Ireland calling for the reintroduction of trade controls on the UK-Ireland borders, ergo, so we do not need to fear such controls. This was in response to the repeated statements by the other witness at the hearing, John McGrane, Director-General of the British-Irish Chamber of Commerce. McGrane emphasised that what businesses on both sides of the border feared most was the reintroduction of trade costs which would reduce the attractiveness of investing and creating jobs in Northern Ireland.

Both witnesses pointed out that, regardless of intentions on either side, it was very unlikely that the status quo could continue, even if the exact trade relationship between the UK and the EU following a possible withdrawal could not be known with certainty. In an important paper published last month, Jean-Claude Piris, who for 22 years was Legal Counsel of the European Council and Director General of the EU Council Legal Services, outlines the various alternatives to EU membership were the UK to vote to leave. He finds none of them attractive to the UK.

Were the UK to leave the single market with its harmonised rules (which is the expressed aim of Brexit advocates) but remain in a preferential trade relationship with the EU, this would still require additional paperwork (for rules of origin purposes), sanitary and phyto-sanitary checks (depending on whether mutual recognition agreements were negotiated in the withdrawal phase), lorry delays at cross-channel ports and the Northern Ireland border, as well as the additional costs of producing for two markets if, over time, regulations on issues such as food labelling, food composition, food additives and novel foods were to diverge over time (and, if they do not, then what is the argument for the UK to leave?).

Kate Hoey, at the end of her questioning, even seemed to suggest that Ireland should itself leave the EU in order to maintain the absence of trade barriers with Northern Ireland, surely a most egregious case of the tail trying to wag the dog.

The EU as an institution has many flaws, many of which are being cruelly exposed in these days. They include a wasteful and ineffective agricultural policy which, despite the worthwhile reforms in recent years, is still not fit for purpose. But the EU as the embodiment of an idea, of collective action to achieve common goals more effectively than any one nation can do on its own, informed by a spirit of solidarity and enlightment, helping to create binding networks across the continent through trade, through movement and through shared decision-making, remains a powerful force. These contrasting views will be at the centre of the Brexit debate if the European Council gives the start signal later this week.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.