I am preparing to give evidence to the Irish Oireachtas Joint Committee on Agriculture, Food and the Marine on Tuesday 17 January on how Brexit might impact on the Irish agri-food sector. Ireland is the EU Member State with the most to lose from Brexit, and the Irish agri-food sector is the most vulnerable economic sector because of its high dependence on the UK as an export market. More than 80 per cent of Ireland’s key beef and dairy production is exported. Although there has been some diversification away from the UK over the past decade, it still takes 43% of all Irish agri-food exports.

In thinking about the potential impact of Brexit on Irish agri-food trade, I draw heavily on the excellent study of the potential impact of Brexit on Irish agri-food trade prepared by two Teagasc economists Trevor Donnellan and Kevin Hanrahan just prior to the Brexit referendum. Although the study was finalised in April 2016, its key messages are still valid after the referendum result. It addresses the impacts on both exports and imports of agri-food products, but in this post I focus solely on exports.

A statistical overview of Irish food and drink exports to the UK

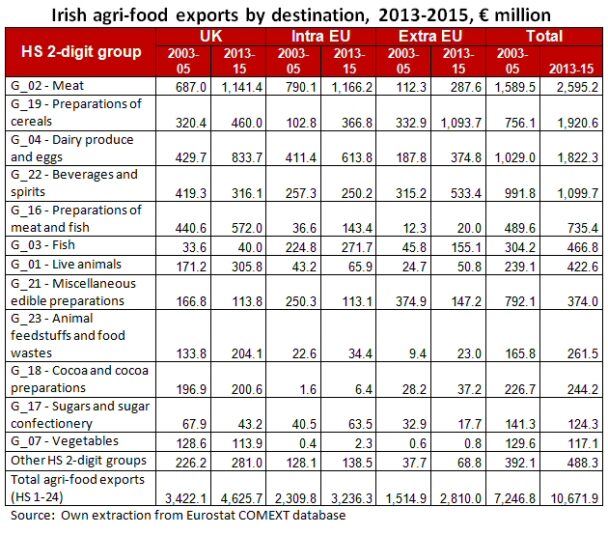

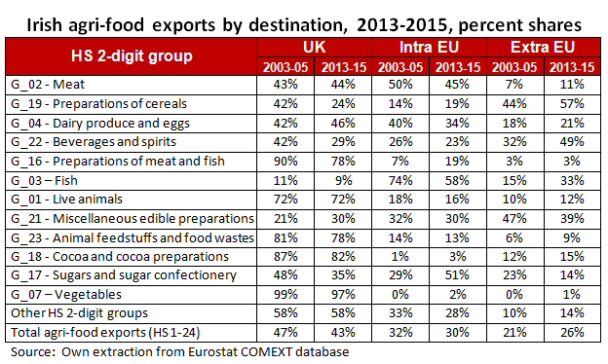

I first present some relevant background statistics on the dependence of different agri-food sectors and product groups on the UK market, using the same Eurostat COMEXT database as in the Teagasc study. Agro-food trade is classified into 24 different 2-digit sections using the Harmonised System (HS) of tariff nomenclature. The first two tables below distinguish the 12 most important HS-2 groups, which together account for 95% of Irish agri-food exports by value. Intra-EU exports are measured excluding exports to the UK.

There are significant differences between sectors at this level of aggregation in their dependence on the UK market. Exports of fresh vegetables (mainly mushrooms), chocolate, meat and fish preparations, and animal feedstuffs, are heavily dependent on the UK market. On the other hand, exports of fish, cereal preparations (where infant formula products have a large share), beverages and spirts, and miscellaneous edible preparations are much less dependent on the UK market.

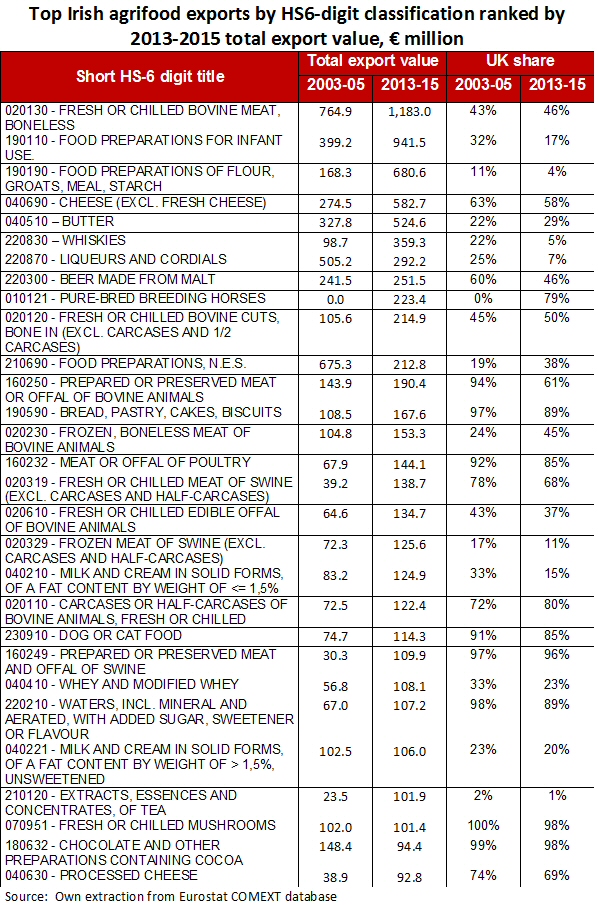

These averages can conceal important differences within these HS-2 digit categories. The following table shows a finer level of disaggregation at the HS-6 level. For example, while 44% of meat exports went to the UK in 2013-15, the proportion was 85% for poultrymeat. While 46% of dairy product exports went to the UK, the proportion was 58% for cheese.

Potential impacts of Brexit on Irish food and drink exports to the UK

How might Brexit affect these export flows? The significance of Brexit for agri-food exports is that the UK will (in my view, almost certainly) leave the EU customs union and will no longer apply the EU’s Common External Tariff. Although it will (again, almost certainly) leave the single market, this will have less immediate significance for agri-food exports.

Leaving the customs union would mean that the UK will regain the ability to set its own tariffs on third country imports and to conclude trade agreements with third countries. The maximum tariffs it could apply will be set by the tariff levels it binds in its WTO schedule of commitments. Statements by the UK Minister for International Trade Liam Fox indicate that it will seek to replicate the EU’s bound tariff schedule as closely as possible.

However, both history and common sense suggest that the UK would apply much lower tariffs on food imports than is currently the case as an EU member, even if it is unlikely to lower its applied tariffs on agri-food products to zero. Why would the UK want to maintain tariffs on oranges, for example? And while it might continue to apply some tariffs on imports of meats and dairy products, these are unlikely to be as high as the EU’s current tariffs.

When Ireland and the UK joined the EU (or the EEC, as it then was) in 1973 and the UK adopted the EU’s Common External Tariff, this resulted in discrimination against, and the diversion of trade from, third countries outside the Union (albeit for some third countries the blow was softened by opening specific tariff rate quotas). Irish exports to the UK were sold at high EU prices rather than the lower world market prices which had previously prevailed on the UK market prior to EU accession (although some Irish agri-food exports to the UK benefited from UK deficiency payments support prior to EU accession under the 1965 Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement).

Thus, throughout the period of EU membership, Irish agrifood exporters benefited from a ‘trade transfer’ as UK consumers were required to pay over-the-odds prices because of the protection given by the Common External Tariff. The UK will now (most likely) leave the customs union and (most probably) adopt a much lower level of tariff protection. It may also enter into trade agreements with competitive third country agricultural exporters granting them more favourable access to the UK market. For both reasons, future prices on the UK market are likely to be significantly lower than today. On top of this, a weaker sterling would also make the UK market less attractive, although only the foolhardy speculate on future movements in exchange rates.

This means that, even with a free trade deal between the EU and the UK which also covers agri-food trade, Irish exporters will lose much of the trade transfer on exports to the UK to which they have become accustomed. The trade diversion resulting from the UK’s adoption of the Common External Tariff in 1973 will unravel and go into reverse.

If the UK and the EU fail to maintain free trade in agri-food products after Brexit, either because of deliberate negotiating strategy or simple chaos around the Brexit negotiations, the position of Irish agri-food exporters is obviously even worse. Just how much worse would depend on the level of tariffs the UK chooses to apply after Brexit. If the UK were to opt for a low level of protection in the first place, securing a free trade agreement becomes less important.

Potential impacts of Brexit on Irish exports to the EU

However, the bad news does not stop there. If the UK market becomes less attractive to Ireland (and thus to all EU exporters) after Brexit, these exports will be diverted to other markets, including other markets within the EU. Again, this effect will be stronger in the absence of a free trade agreement if EU exporters face Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs on exports into the UK.

The Teagasc report investigates the likely negative effect on EU market prices of possible trade diversion of current EU exports to the UK to the EU market after Brexit. The Teagasc economists note that this negative impact would depend on (1) the importance of UK self-sufficiency and import demand as a determinant of the EU27’s net trade position in specific commodity markets, and (2) the world price of the specific commodity relative to the price in the EU.

Other things being equal, if the UK is close to self-sufficiency in a particular sector and if world prices are similar to EU prices, then Brexit would not be expected to significantly impact EU market prices in that sector. This would characterise the likely outcome of Brexit for the EU cereals sector.

Conversely, other things being equal, if the UK has a substantial deficit in a particular commodity area and if world prices are considerably below the EU level, then the greater the potential for an impact on EU prices. This would characterise the likely outcome of Brexit for the EU beef sector.

Finally, if the UK is an exporter of a commodity and if world prices are considerably below the EU level, there is the potential for an increase in EU market prices, at least in the absence of a free trade agreement. This might characterise the possible outcome of Brexit for the EU sheepmeat sector. With a free trade agreement in place, this outcome is less certain. Currently, UK exports of sheepmeat to the EU are balanced by UK imports of sheepmeat from third countries, notably New Zealand. If, after Brexit, the UK provides even greater access to third country sheepmeat imports, this could encourage even more UK sheepmeat to find an outlet on the EU market under the free trade scenario. In this scenario, paradoxically, UK sheepmeat exports to the EU could even increase.

Teagasc scenarios

The Teagasc economists make some illustrative calculations of the likely impact on the value of Irish agri-food exports as a result of Brexit. They assume a worst-case scenario in which tariffs are re-imposed on trade between the EU and the UK.

Their analysis makes the simplifying but strong assumption that the volume of Irish agri-food exports would continue as before, but that their value would decrease because some proportion of the exports now sold on the UK market would be diverted to another EU market at a significantly discounted price. That is, they assume that the unit value of the diverted exports would be lower than the current unit value obtained by these exports on the UK market.

They then simulate four scenarios which differ in two parameters (1) the volume of current UK trade diverted to other EU markets, and (2) the size of the discounted unit value for these diverted exports. In their base scenario, they assume that 21.5 per cent of UK exports are diverted, and that the size of the discount is 15 per cent (the rationale for assuming these percentages is given in their paper). In their other scenarios, they either increase the share of UK exports that are diverted, and/or they increase the discount in the unit value when diverted to other EU markets.

The smallest impact of Brexit in the base scenario is an annual loss of agri-food export value of around €150m or 1.4 per cent of agri-food export value. The largest impact showed a reduction in total Irish agri-food exports of 8 per cent or €800m.

In my view, these estimates are gross underestimates of the adverse impact on the value of Irish agri-food exports if the UK leaves the customs union.

First, they assume that Irish agri-food exports to the UK after Brexit will continue to receive the current unit value. As I argue above, I believe this would be a very unlikely outcome if the UK leaves the customs union. This would mean that there would also be a substantial loss of value for future exports to the UK as well.

Second, we noted that the Teagasc study explicitly assumes no change in the volume of agri-food exports. With a substantial fall in the profitability of exports to both UK and EU markets, this is highly unlikely to be the case.

Third, the Teagasc study suggests that these adverse outcomes would only occur in the situation where no free trade agreement is concluded between the EU and the UK after Brexit. It anticipates that an outcome with a free trade agreement would not have a significant impact on the agri-food sector in Ireland.

I argue above that this is too starry-eyed a perspective. While securing a free trade agreement after Brexit is important, its importance depends on whether the UK stays in the customs union or not. If the UK withdraws from the customs union (as I expect it will), its post-Brexit trade policy is likely to be much less protectionist of food and agriculture, and thus UK market prices for agri-food exports will be at least somewhat lower than today. A free trade agreement if the UK leaves the customs union would help to mitigate the adverse consequences, but it could not avoid them.

Conclusions

Bord Bia, the Irish Food Board, has just published its Export Performance and Prospects 2016-17 for the Irish agri-food sector. It reported the seventh consecutive year of growth for food and drink exports. In value terms, food and drink exports have increased by 41% in 2016 over 2010 which makes the sector one of the star performers in the recovery of the Irish economy after the 2008 financial melt-down.

Brexit threatens to undermine the continued success of this sector. The Teagasc analysis is very useful in highlighting that, following a hard Brexit, the Irish agri-food sector would need to rebalance to some degree its trade in agri-food products with the UK, the EU and the Rest of the World.

The adverse effects on the value of Irish agri-food exports arising from this rebalancing following Brexit would be largely avoided if (1) the UK stays in the customs union for agri-food products, and (2) a free trade agreement between the EU and the UK avoids the reintroduction of tariffs on trade between the two partners. Some adverse effects would arise if the UK also leaves the single market, but these are of of much smaller order of magnitude than if the UK leaves the customs union.

The UK government has not yet announced any formal decision on whether it intends to stay in or leave the customs union. The argument for staying in the customs union is largely to avoid costly rules of origin requirements particularly for the car industry.

Under WTO rules, a customs union is required to eliminate duties on “substantially all trade” between the constituent parties to the union. This is normally interpreted to mean that no significant sector, such as agriculture, can be omitted entirely. However, the one current example of an EU customs union with another territory, the customs union with Turkey, does not cover agriculture, although there is a parallel free trade agreement liberalising some agricultural trade.

The Common External Tariff on agri-food products imposes a substantial cost on the UK economy because, as a net importer, the UK collects substantial tariff revenue on its imports of agri-food products from third countries which is remitted to Brussels. The total customs duties collected by the UK in 2015 (of which 75% was remitted to Brussels allowing for the costs of collection) amounted to €3.2 billion although the agricultural share of this amount is not separately isolated.

However, in the Turkey-EU customs union, although Turkey applies the EU’s Common External Tariff on non-agricultural imports, the revenue it collects remains part of its own budget revenue and is not part of the EU budget. This would remove an important objection to the UK staying inside the customs union.

However, the UK seems determined to regain the possibility to conclude its own trade agreements with third countries, which would be incompatible with continued membership of the customs union. For this and other reasons, it seems to me highly unlikely that the UK will ultimately end up staying in the customs union.

If it were to come about, the Irish agri-food sector would be the one breathing the greatest sigh of relief.

This post was written by Alan Matthews