Last week, the European Parliament secretariat (Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies) presented a briefing authored by Albert Massot and Francois Negre to the AGRI Committee comparing the Commission’s CAP legislative proposals for the period after 2020 with the current regulations. It consists of two documents: a relatively short contextual statement, and an annex containing six ‘Dashboards’ which in a two-column format set out in specific detail how the CAP reform package (2021-2027) proposed by the Commission on 1st June 2018 compares with the current CAP (2014-2020) regulations, topic by topic. It makes a very useful contribution in structuring the debate around the Commission’s CAP proposals.

In this post, I want to pick up on just one issue addressed in the briefing, namely the budgetary framework. In previous posts (here and here), I have tried to establish what the Commission’s MFF proposal made on 2 May 2018 implies for the future CAP budget. This has been a frustrating process because a key Commission document circulated to the Parliament’s Budget Committee seemed to contain an obvious error (see discussion in the second of my two posts). Some further insights into the budgetary framework were since provided in a recent European Court of Auditors report discussing the MFF proposal.

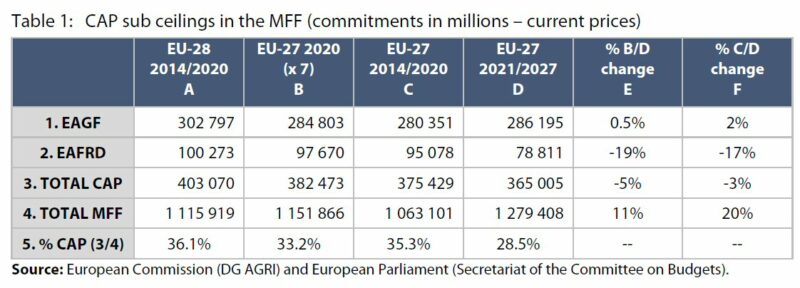

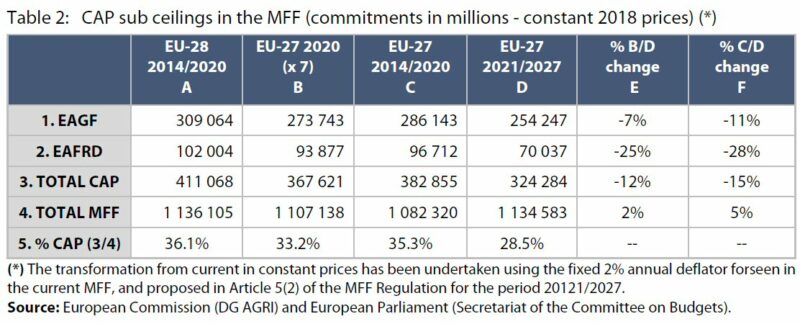

However, this European Parliament briefing sets out the numbers in what I think will be the definitive version. They can be consulted in the paper itself, but for convenience I reproduce them here. The proposed CAP budget for the 2021-2017 is compared in both nominal and real terms with the CAP budget available in the 2014-2020 period for both Pillars, taking into account the difference made by the departure of the UK, and using two different points of reference. The tables compare the total resources allocated to the CAP over the two seven-year MFF periods adjusted for the UK departure, as well as comparing the allocation for the 2021-27 MFF with the last year of the current MFF (multiplied by seven). Note that the briefing does not compare the two end-years in each MFF, as I did in this post. In passing, one can remark that the Commission would have saved a lot of aggravation by making this information available at the time the MFF proposal was published.

It must be stressed that this is still a Commission proposal. It assumes that the European Council will go along with the proposed increase in the MFF ceiling (from 1.00% to 1.11% of EU27 GNI). Because the proposal for the 2021-2027 MFF includes the budgetisation of the European Development Fund, the actual increase proposed by the Commission is somewhat smaller, from 1.03% to 1.11% of EU27 GNI. It also assumes that Member States in the European Council will agree to the change in the proposed structure of EU spending, with a higher share of the MFF going to new challenges and a smaller share going to the ‘traditional’ big ticket items of cohesion and agricultural spending.

The figures show that, comparing the 2021-2027 MFF to the last year of the current MFF (2020 multiplied by seven) gives a smaller increase (but larger decrease) relative to comparing the size of the two MFFs as a whole. The Commission prefers to emphasise the comparison with the year 2020 multiplied by seven. On this basis, CAP spending in nominal terms is expected to fall by 5%. However, if we compare total MFF resources for the two periods, the fall is only 3%. In either case, Pillar 1 spending in nominal terms is projected to increase.

When the figures are compared in constant price terms, these rankings are reversed for the CAP. Now it is the comparison of total resources in the two MFF periods which shows the largest decreases.

Implications for rural development expenditure

The tables also confirm what has been long recognised, that the Commission proposes a substantial reduction in Pillar 2 resources in both nominal and, especially, real, terms. However, three points need to be kept in mind when trying to project the likely impact on total rural development spending.

First, the resources devoted to Pillar 2 in the current MFF period (€100.3 billion in current prices and €102.0 billion in constant 2018 prices) are calculated after the flexibility decisions of Member States to transfer resources between the two Pillars. The Pillar 2 allocation in the 2021-2027 MFF is before Member States have made their decisions on transfers between Pillars. In the current MFF period, Member States have made a net transfer of resources from Pillar 1 to Pillar 2.

This option to transfer resources between the Pillars is maintained and expanded in the Commission’s legislative proposal. In addition to the possibility to transfer 15% between pillars, Member States will also have the possibility to transfer an additional 15% from Pillar 1 to Pillar 2 for spending on climate and environment measures (without national co-financing). We might thus expect a similar net transfer to Pillar 2 to happen at the start of the next MFF as well. Also, the scope to finance RD-like measures using a Member State’s Pillar 1 ceiling (limited to ANC payments in the current CAP) will be expanded through the obligatory eco-scheme to fund agri-environment-climate expenditure without necessarily transferring these resources to Pillar 2.

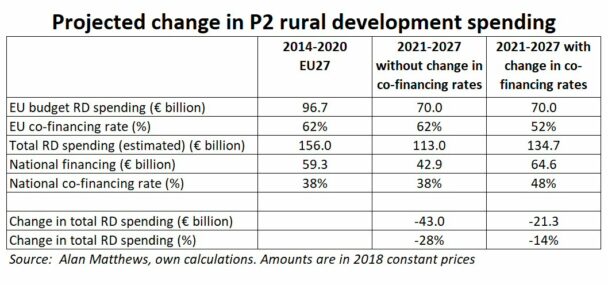

Second, the Commission is proposing a reduction in the EU co-financing rate for Pillar 2 expenditure of 10 percentage points, meaning that Member States will be expected to contribute additional national resources to fund rural development programmes. This will help to maintain the overall volume of spending on Pillar 2 projects, regardless of any decisions taken to use the flexibility to transfer resources between Pillars. However, it will not be sufficient on its own to prevent an overall reduction in Pillar 2 spending, as shown in the following table.

The EU budget RD spending figures are taken from Table 2 in the European Parliament briefing comparing total MFF spending (adjusted for the UK departure) in the two periods in real terms. The average EU co-financing rate is derived from the figures for EU and national RD spending in this DG AGRI publication, and I assume this percentage is also valid for the EU27 in the 2014-2020 period.

The next column looks at what would happen to total RD spending in the absence of any change in co-financing rates. Total RD spending would fall by 28%, which is the same reduction as for EU Pillar 2 spending alone.

The final column shows the impact of reducing the EU co-financing rate by 10 percentage points. We assume that the composition of spending across programmes and regions eligible for different co-financing rates does not change. This will crowd in additional national RD spending; in fact, national co-financing of EU rural development programmes would slightly increase compared to the current MFF period. However, the additional national financing is not sufficient to offset the cut in EU budget spending. Overall, there would still be a cut of €21 billion in total RD spending, a reduction of 14% in real terms compared to the current period.

Third, it is important to underline that Member States are able to top-up rural development spending out of their own resources. If there is no EAFRD co-financing associated with this spending, the Member State must seek State aid approval for this expenditure. Where the measures are exactly similar to those that can be funded under Rural Development Programmes (”RD-like”) and are limited to SMEs (thus covering measures directed at most farmers), there may be scope to notify these measures under the Agricultural Block Exemption Regulation. This is a simplified procedure intended to reduce delays and the bureaucratic hassle of formally seeking Commission approval for State aid expenditure.

If this is not the case, Member States can seek approval from the Commission under the Agricultural Guidelines for State aid in the agricultural and forestry sectors. Provided the criteria in these Guidelines are met, such State aid will be approved. Member States make considerable use of these State aid possibilities for RD spending in the current MFF period. Again, this is likely to continue in the next MFF period. As national expenditure of this kind will be expected to contribute to the achievement of the nine specific objectives spelled out for the CAP Strategic Plans, it will be important to include this proposed expenditure when submitting these Plans for approval to the Commission.

For these three reasons, it is not possible at this stage to state definitively whether total spending on RD projects will increase or decrease in the years after 2020. Much is left to the decisions of Member States when drawing up their Strategic Plans.

Critical reactions

There has been a strong critical reaction from the European Parliament, many Member States and farm unions to the CAP budget proposals in the MFF, as Budget Commissioner Oettinger admitted to the General Affairs Council at its MFF discussion on 18 September last. The Commissioner has emphasised that the withdrawal of the UK as a significant net contributor is one reason why cuts are necessary to ‘traditional’ programmes. The mantra chosen by the critics has thus been that “farmers should not bear the cost of Brexit”. The implication is that the gap should be made up by additional Member State contributions.

The European Parliament briefing notes that “Since 1992, the date of the first significant overhaul of the CAP and the substantial increase in the volume of direct aid, agricultural expenditure remained stable in real terms… The CAP budget has never suffered such an overall reduction in any of the previous reforms. The explanation lies in the cumulative effect of Brexit and in the need to finance the new challenges facing the EU.”

While one might quibble with the conclusion that the CAP budget has never been cut in real terms (in the 2014-2020 MFF it was held constant in nominal terms implying a real cut at that point), the proposed 3-5% cut in nominal spending on this occasion is a break with the past, brought about for the reasons mentioned in the briefing.

The European Parliament’s resolution of 30 May 2018 on the Commission’s MFF proposal “Deplores the fact that this proposal leads directly to a reduction in the level of both the common agricultural policy (CAP) and cohesion policy, of 15 % and 10 % respectively”. It went on to call “to maintain the financing of the CAP and cohesion policy for the EU-27 at least at the level of the 2014-2020 budget in real terms.”

The draft COMAGRI Opinion prepared by Peter Jahr MEP for the Parliament’s interim report on the MFF proposal to be voted in plenary in November “Reiterates its call for the CAP budget to be maintained in the 2021-2027 MFF at least at the level of the 2014-2020 budget for the EU-27 in real terms, given the fundamental role of this policy; reaffirms its view that agriculture must not suffer any financial disadvantage as a result of political decisions such as the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU or the funding of new European policies.”

On 31 August, the AGRI Committee Chair Czeslaw Adam Siekierski put down a question for oral answer by the Agriculture Commissioner to “ask the Commission and the Council to increase the proposed CAP budget to bring it back to the current EU-27 level, and for it to be maintained in real terms over the duration of the next MFF period to ensure proper funding of the CAP objectives and avoid any possibility of re-nationalisation in the future.”

At the June 2018 AGRIFISH Council meeting, the French delegation presented a joint memorandum on the CAP budget in the context of the future MFF on behalf of a group of member states (Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, supported by Croatia, Cyprus, Hungary, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Romania and Slovakia). The memorandum regrets the proposed reduction of the CAP budget in the context of the MFF “as this would threaten the viability of European farming, and requests that the future CAP budget is increased and brought back to the current EU-27 level”. Important to underline here is that the memorandum does not specify whether “the current EU-27 level” is defined in nominal or real terms. One might impute that, because the memorandum does not make an explicit reference to real terms, it is implicitly looking for this restoration in nominal terms.

Noting that last caveat, the Parliament’s reactions all ignore that the largest expenditure item in the CAP budget is direct payments, they account for 73% of total spending. Direct payments were introduced in 1994 as compensation for reductions in market intervention prices at the time. The value of these payments has been more or less maintained in nominal terms since then. As Table 1 shows, this will continue to be the case in the next MFF under the Commission proposal. To the extent that the CAP budget has been maintained in real terms, this is because of successive enlargements of the EU. There has never been a commitment to inflation-proof the value of direct payments.

The CAP share in the EU budget

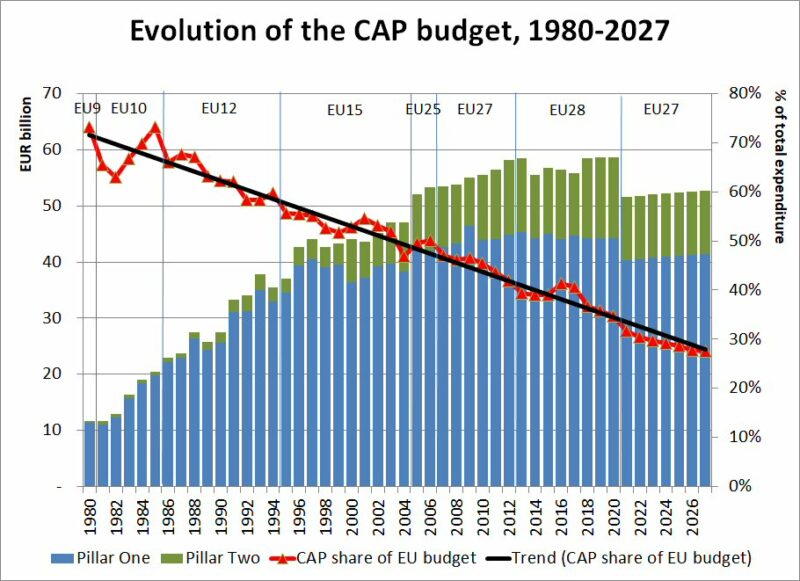

Yes, there would be a small cut (of around 3-5%) in the total CAP budget in nominal terms in the next MFF period under the Commission proposal. But when we look at the trend in the share of the CAP in total EU budget spending (shown in the next chart), the fall in the CAP budget share in the 2021-2027 period follows very closely the trend of the previous four decades.

The message from the chart is that there is no real break in the trend in CAP expenditure in the Commission’s MFF proposal, it is very much business as usual. The CAP share in the total EU budget was around 73% in 1980, and is projected to fall to around 27% in 2027. This is very much in line with the trend. The Commission could no doubt refine the figures behind this chart (see Technical Note below) so that they are more comparable, but I don’t think this would change the underlying conclusion

The Commission would do well to promote this chart in the coming months in making its case that the proposed structure of spending in the next MFF is a justifiable compromise between competing demands.

Technical note: There are two definitional problems in comparing the share of CAP spending in total EU budget spending over the period 1980-2027. The first is that the data for the period 1980-2017 are based on actual spending (derived from the DG BUDGET Financial Reports and, for 2000-2017 from its interactive workbook). We do not know what actual spending will be for the decade ahead.

For the period 2018-2027, therefore, the data are based on commitment appropriations in current prices derived from the MFF tables. Thus the percentage figures for the CAP share in the total EU budget are not exactly comparable for the periods 1980-2017 and 2018-2027.

The second adjustment that must be made is that the MFF totals for the period 2021-2027 include commitment appropriations for the European Development Fund (EDF). In previous periods this spending has been outside the MFF. Thus, I have subtracted estimated EDF spending from the MFF totals set out in the Commission’s 2 May 2018 proposal to ensure comparability. This spending is not given directly in the MFF proposal as the EDF is included in the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation (NDIC) instrument. The European Court of Auditors report on the MFF puts EDF spending in the proposed MFF at current prices at €28.2 billion over the 7-year period. I have distributed this spending over the seven years in line with the growth in nominal spending for the NDIC Instrument as a whole.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Photo credit: Davy Landman, Sunset at Roermond,NL, used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.