World food prices are on the rise again. In December 2010, they exceeded the dramatic peak they had reached during the global food crisis in 2007/08. Add to this threatening megatrends, such as population growth and climate change, and think of recent news about the severe drought in Russia or the once-in-a-century flooding in Australia, both major staple food exporters. Who wouldn’t get an uneasy feeling that the specter of famine might come to haunt Europe again?

The European Commission has concluded in its communication on the post-2013 CAP that the CAP must preserve the EU’s food production potential, ‘so as to guarantee long-term food security for European citizens’. Similarly, ministers of agriculture from 22 member states claim in their Paris Declaration that ‘only an ambitious, continent-wide policy can safeguard Europe’s independence’.

Surprisingly, however, there are no scenarios and no calculations to substantiate this perceived threat. Only the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) has conducted a Food Security Assessment. The lessons are clear-cut: there are no discernible dangers for the UK. In a recent working paper, I have looked at the entire EU.

EU food production per capita has constantly increased in the past and far outstrips dietary energy requirements. The share of income that households spend on food has steadily declined. By now, food prices are so low compared to income that even a 10-fold increase in the farm gate price of staple crops would be far off from provoking food scarcity in the EU. Forecasts predict roughly stable or increasing production quantities for the EU – even in the case of subsidy and tariff cuts. The expected main effect of climate change during the coming decades will be to shift production from southern to northern Europe without significantly curtailing overall production.

If food prices rose dramatically, the EU could increase the agricultural area used for growing cereals; in particular, by cutting back on biofuel and livestock production. Furthermore, agricultural labor and capital input could be multiplied. An additional measure would be to enhance investments into agricultural productivity.

The EU does thus not depend on imports for its food security. Still, it’s interesting to have a closer look at EU food imports. Since food prices are so low compared with EU wealth that the EU could afford sufficient imports even if prices rose tenfold (always speaking of basic staples, not caviar and passion fruit), only export restrictions could impair the EU’s import potential. A number of considerations show how unlikely this threat is.

Agricultural markets are becoming thicker: world food trade has increased by 230% between 2000 and 2008 according to the FAO. The greater the volumes, the more food can still be bought on the world market if a given amount of supplies is interrupted.

Export concentration has been low, or at least decreasing, during recent decades in the most important agricultural markets, as Defra notes in its Food Security Assessment. The concentration of countries’ share in world food exports matters because export restrictions are more lucrative and can be more easily upheld if most of the market is in the hands of one or few suppliers.

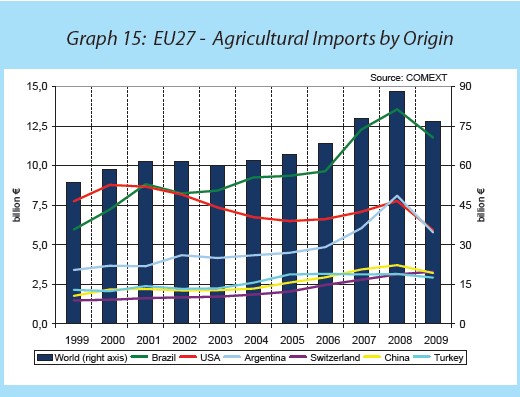

A significant share of EU imports comes from highly reliable exporters: the US, Switzerland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. These countries could greatly expand their exports to the EU if the need arose. The other main source of exports to the EU, South America, is decently stable. The figure below shows the market shares of key exporters to the EU (it stems, as the following figures, from the DG Agri MAP newsletter).

Food is a homogenous good if the issue is not taste but calories. If exports of wheat were seriously curtailed, they could be replaced by rice, maize and other grains. Export restrictions are therefore less harmful to importers and less attractive to exporters.

Food is mostly traded on a spot market and can be easily transported. Food thus differs greatly from oil and gas where imports hinge on long-term contracts, pipelines and suitable refineries.

Food production in major exporting countries can be more easily increased than energy production (beyond currently available capacity) as the latter depends on long-term capital investments. If some suppliers restrict their exports, it is thus easier for their competitors to pick up market shares.

No prolonged and encompassing phases of export restrictions have occurred since the Second World War. Export restrictions taken during the 2007/08 price spikes were usually of short duration and limited to one or a few products.

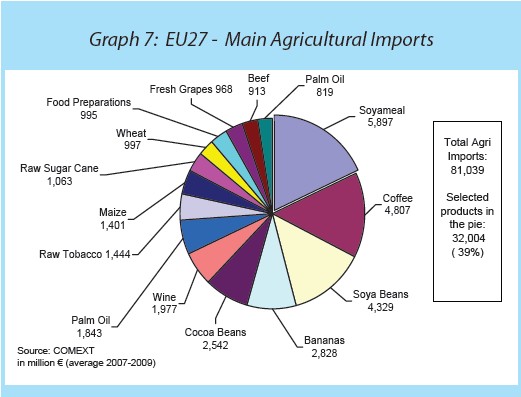

The EU imports relatively little staple food. Most agricultural imports are either feedstuff (soya), ‘luxury’ products (coffee, tea, tobacco, sugar, exotic fruits, meat, food preparations) or products with multiple non-food uses (palm oil). The figures below show this at a highly aggregated level and for the main imported products.

All readers are cordially invited to discuss these issues at a lunch seminar at ECIPE in Brussels on January 26.