In October 2014, the European Council agreed the 2030 policy framework for climate and energy policy. The framework sets out the European Union (EU)’s commitment to a binding target of at least a 40% domestic reduction in economy-wide greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030 compared to 1990, with the reductions in the Emission Trading System (ETS) and non-ETS sectors (NETS) amounting to 43% and 30% respectively by 2030 compared to 2005. The European Council also set an EU target of at least 27% for the share of renewable energy consumed in the EU in 2030, and an indicative target at the EU level of at least 27% for improving energy efficiency in 2030 compared to projections of future energy consumption based on current trends. This will be reviewed by 2020, having in mind an EU level of 30%.

In a previous post, I examined the likely treatment of agriculture in this 2030 Climate and Energy Framework in the run-up to the European Council meeting which agreed the 2030 targets. However, it is only with the publication by the Commission of the Effort-Sharing Regulation (proposing a distribution of NETS targets among member states) and its proposed LULUCF Regulation (addressing how the LULUCF sector might be integrated into the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework) that we can begin to understand more concretely the likely implications for agriculture.

Agricultural non-CO2 emissions are included in the NETS sector and are therefore covered by the NETS target to reduce emissions in 2030 by 30% compared to 2005. In this post, we look at the implications of this target for the scale of the challenge for agricultural mitigation for the EU as a whole and for individual member states. The surprising conclusion is that the package implies almost no additional demand for agricultural mitigation for the EU as a whole beyond what is expected with current policies in place, although this is unlikely to be the case for a small number of member states. Whether farmers in different EU member states are required to undertake additional mitigation as a result of the package will depend on the decisions actually made by individual countries on how best to meet their NETS targets after 2020.

Policy context

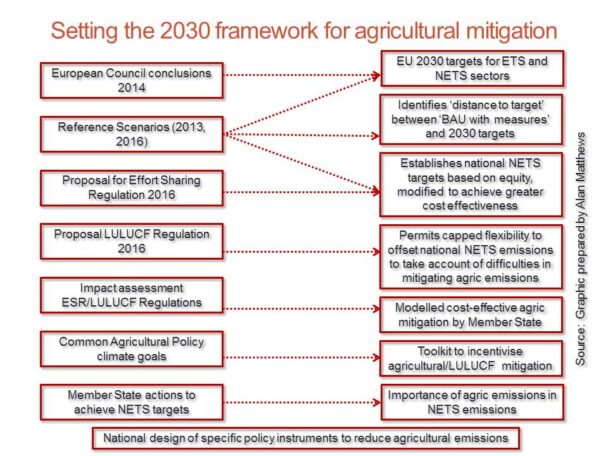

Assessing the scale of the challenge for agricultural mitigation in each member state means following a series of interlinked steps, as set out in the following graphic.

- First, there is each member state’s 2030 NETS target itself, as proposed in the Commission’s Effort Sharing Regulation, which takes into account the new flexibility provided by the proposed LULUCF Regulation.

- Second, there is the ‘distance to target’. This is the gap between expected emissions in 2030 which are estimated in the Commission’s 2016 Reference Scenario on the basis of current policies (that is, assuming full implementation of existing legally binding targets as well as adopted policies in areas such as energy efficiency, energy performance of buildings, emissions reductions in transport, etc). This ‘distance to target’ drives the need for additional mitigation efforts at the member state level to meet the 2030 NETS targets taking account of LULUCF flexibility.

- Third, there is the share of agricultural emissions in NETS emissions in 2030 in the Reference Scenario which gives some indication of the importance that is likely to be given to agricultural mitigation in each member state in these additional mitigation efforts.

- Fourth, depending on the scale of agricultural mitigation sought, member states will have to design and implement schemes and initiatives to achieve these desired reductions. The NETS targets are addressed to member states. There are no specific targets for agricultural emissions in the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework. It is up to each individual member state to decide on the sectoral interventions and initiatives it will take in order to meet its national target. Where member states pursue additional agricultural mitigation, the Common Agricultural Policy can provide funding for some interventions. Others will be the responsibility of member states. Member states will have to decide on the balance between R&D and advisory work, regulation and subsidised incentives in order most effectively to achieve their desired reductions

In this post, I only identify the scale of the likely challenges for agricultural mitigation by 2030, leaving a discussion of policies and interventions to another day.

Impact of 2030 targets on agricultural emissions

The 2014 Framework impact assessment. An initial analysis of the expected contribution from agricultural mitigation was made when presenting the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework in 2014. The impact assessment assessed a number of different scenarios with respect to the level of EU ambition for GHG emissions reduction (either 35%, 40% or 45% reduction compared to 1990, whether specific renewable energy targets were included or not, and whether specific energy efficiency targets were included or not). Scenarios with ambitious energy efficiency policies typically reduce GHG emissions more in the NETS sectors. Scenarios were also distinguished depending on whether they met not only 2030 targets but also the EU’s 2050 target of an 80% reduction in emissions (see footnote at the end of this post for what this means).

For the scenario eventually adopted by the European Council (an overall 40% GHG reduction target, split 43% ETS/30% NETS and a renewable energy target of 27%), agricultural non-CO2 emissions were expected to reduce by 28% compared to 4% in the 2013 Reference Scenario (see Table 40 of the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework Impact Assessment). Separate simulations by the Joint Research Council in the EcAMPA 2 project highlighted that additional mitigation action of this order of magnitude would have significant negative effects on agricultural production.

In the modelling, this mitigation is driven by assumed carbon values taking into account a limited number of technical mitigation options. It would be up to member states to decide how these mitigation reductions might be actually achieved in practice and to introduce the concrete policies that would be required to incentivise them.

The 2016 ESR impact assessment. The size of the presumed contribution from agricultural mitigation has been updated for the ESR Impact Assessment, using the updated 2016 Reference Scenario and re-running the models to ensure achievement of the European Council targets. The new scenarios report a very different result for what additional mitigation might be required in agriculture.

Two policy scenarios reflecting the main elements of the 2030 climate and energy framework agreed by the European Council in 2014 were simulated, EUCO27 and EUCO30. EUCO27 is a scenario that achieves the at least -40% GHG reduction target (with the split ETS/non-ETS reducing by -43%/-30% in 2030 compared to 2005), a 27% share of renewables and 27% energy efficiency improvements. In this scenario, the 27% energy efficiency target is met as a consequence of meeting the overall 40% reduction in GHG emissions and it is not an additional binding constraint. In the EUCO30 scenario, the energy efficiency target is increased to 30% to anticipate the review to be undertaken before 2020 to set the level of ambition.

Both scenarios start from the EU Reference scenario 2016 and add the cost-effective policies needed to meet their targets. They also incorporate coordination policies which enable long term decarbonisation of the economy and which correspond to the “enabling conditions” which were modelled in the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework impact assessment (see footnote at the end of this post).

Specifically, in 2030 carbon values of €0.05 are applied to non-CO2 GHG emissions in order to trigger cost-effective emissions reductions in those sectors including in agriculture. After 2030 carbon values are set at the EU ETS carbon price level. It is puzzling to understand why such a low carbon value prior to 2030 has been used. It also seems to contradict other statements (for example, in the LULUCF impact assessment, the projected mitigation beyond reference on Afforested, Deforested and Agricultural land was assessed using a carbon price of €20/tonne, on the basis that this was a similar carbon value to that applied in other NETS sectors, see LULUCF impact assessment, p. 38).

In the 2016 Reference Scenario, agricultural emissions are expected to reduce by slightly less than in the 2013 Scenario (-2.4% compared to -4%). Unfortunately, the ESR impact assessment does not contain a similar table to that in the Climate and Energy Framework impact assessment spelling out the expected amount of agricultural mitigation under the modelling assumptions. However, the impact assessment concludes as follows:

In the EUCO27 scenario, energy efficiency delivers a large part of GHG emissions reduction in the ESD/ESR sectors. This reduction is complemented by cost-effective reductions in non-CO2 emissions – mostly in agriculture.

The EUCO30 scenario is constructed similarly to the EUCO27 scenario, but raises the ambition level of the specific energy efficiency policies in a cost effective way… A relevant implication is that more ambitious energy efficiency policies deliver all necessary reductions in ESD/ESR sectors, and no reductions in non-CO2 sectors such as agriculture beyond Reference take place” (p. 137).

This is indeed a startling reversal of the conclusion in the 2014 impact assessment published just two years previously. With just a little bit more effort to improve energy efficiency over and above what is expected in the period to 2030, there will be no requirement for further reductions in agricultural emissions during this period beyond those already expected from policies in place. Even under the expected energy efficiency improvements arising just from meeting the 40% reduction target (in the EUCO27 scenario), the required additional effort in agriculture will be very limited. The modelling now suggests that member states will not find it necessary to trouble farmers to tackle climate change for another 15 years.

Consequences of 2030 targets for individual member states

The Commission modelling seeks to determine the most cost-effective mitigation options for the EU as a whole. However, under the proposed Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) member states will have individual national targets for their NETS sector. We now assess the likely importance of additional agricultural mitigation assuming that member states seek to meet these targets through domestic action alone.

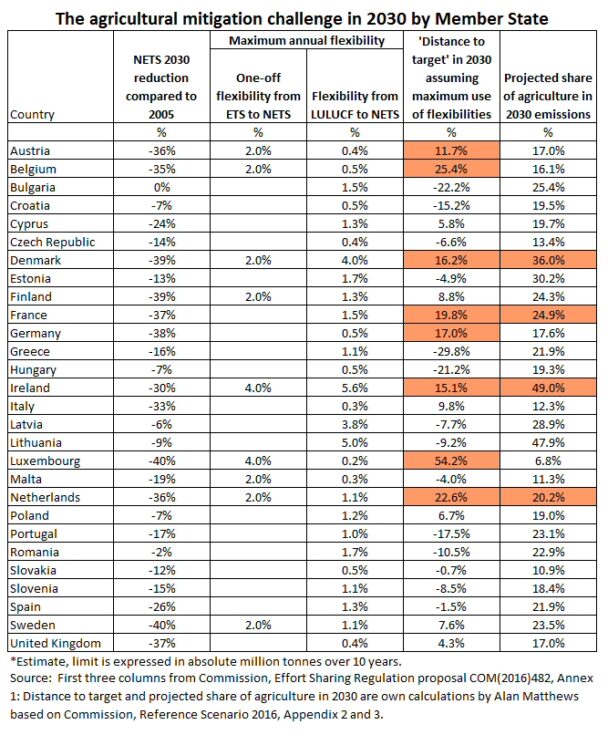

National targets under the Effort Sharing Regulation. The ESR defines national targets in line with an EU-wide reduction of 30% by 2030 in the NETS sectors compared to 2005. The proposal differentiates targets among member states based on GDP per capita to reflect fairness, while providing for cost-effectiveness as endorsed by the European Council. Member states contribute to the overall EU reduction in 2030 with targets ranging from 0% to -40% below 2005 levels (see table below). Annual emission levels are determined based on a linear trajectory starting with average emissions for 2016-2018 based on the most recent reviewed GHG emission data. The basis for the allocation is set out and justified in the impact assessment accompanying the ESR proposal.

LULUCF and other flexibilities. The ESR includes a new flexibility which allows for a limited use of net removals from certain Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) accounting categories, while ensuring no debits occur in the LULUCF sectors, to account for member state compliance towards the targets in the NETS sectors if needed.

This is in line with guidance provided by the European Council noting the lower mitigation potential of the agriculture and land use sector, and the importance of examining the best means to optimise this sector’s contribution to greenhouse gas mitigation and sequestration, including through afforestation.

The overall amount of LULUCF credits that can be used to offset NETS emissions is capped at 280 Mt CO2-eq from deforested land, afforested land, managed cropland and managed grassland (credits from forest management cannot be used in the NETS sector). This total is allocated across member states based on the relative share of agricultural non-CO2 emissions in total NETS emissions (see table below).

An additional new flexibility has also been included for member states with national emission reduction targets significantly above both the EU average target and their cost effective reduction potential, as well as for member states that did not have free allocation for industrial installations in 2013. The flexibility allows eligible member states to facilitate the achievement of their NETS obligations through the cancellation of EU ETS allowances (see table below). This is a once-off flexibility for the commitment period as a whole which must be chosen prior to the beginning of the period. The total annual emission allowances (AEAs) made available in this way are represented in the table below in terms of their annual equivalent spread out over ten years.

Neither of these options comes for free. In the case of the LULUCF offsets, many member states will have to undertake additional mitigation in the LULUCF sector in order to generate sufficient usable credits. If the cost of achieving this additional LULUCF mitigation exceeds the cost of reducing emissions in the NETS sector, member states may decide to forego this option.

In the case of the option provided to some member states to achieve their NETS targets by cancelling ETS allowances, those member states making use of this option would forego the associated auction revenue. Again, these member states will have to decide (before 2020) whether the foregone revenue is likely to be less than the cost of achieving the additional mitigation required through domestic action in the NETS sectors or acquiring additional AEAs from surplus member states. Some member states may decide to hedge their bets and only apply for a proportion of the AEAs they would be entitled to transfer.

These new flexibilities are in addition to the continuation of the existing flexibility available to member states to achieve their annual limits including flexibility over time through banking and borrowing of AEAs within the commitment period, as well as flexibility between member states through transfers of AEAs.

Distance to target in 2030. For the purpose of calculating each member state’s ‘distance to target’ in 2030, I assume full use will be made of the permitted flexibilities. The modified NETS targets must then be compared to expected NETS emissions in 2030 on a ‘business as usual’ scenario. The Commission, using a suite of modelling tools, estimates these expected emissions in its regularly updated Reference Scenario. The impact analysis of the ESR proposal was based on the 2016 Reference Scenario.

As for any projections exercise, the 2016 Reference Scenario is based on a number of policy assumptions. Estimates are made of future population and economic growth rates, energy prices, the level of agricultural activity and technological progress in GHG-reducing technologies. Full implementation of existing legally binding targets as well as of adopted policies (up to end-2014) relating, among others, to energy efficiency, energy performance of buildings, CO2 reductions from road vehicles, renewables, landfill sites, the circular economy or fluorinated greenhouse gases, is assumed.

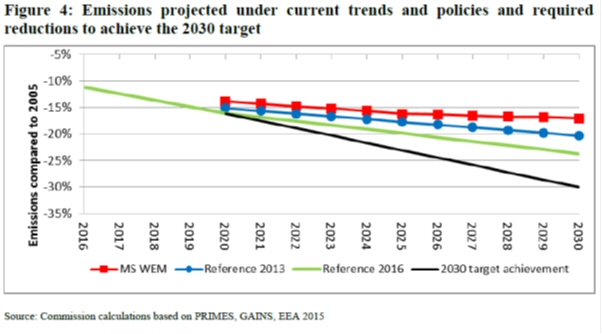

In the 2016 Reference Scenario, NETS emissions are projected to decrease by around 24% below 2005 levels in 2030. For the EU as a whole, when allowance is made for full use of the flexibilities by those member states which can make use of them, the ‘distance from target’ in 2030 is 7%. That is, additional national efforts to reduce NETS emissions by this amount below the baseline in the Reference Scenario are required.

As shown in the table below, the challenges are very different for individual member states. The 2030 reduction percentages are allocated relative to 2005 mainly on the basis of GDP per capita. But national GHG emissions evolve very differently in the Reference Scenario over the period 2005 to 2030 on the basis of expected economic growth rates and the policies that each country has in place. This gives rise to a very disparate picture if countries are ranked on the basis of ‘distance to target’ in 2030 rather than on the basis of the reduction percentages between 2005 and 2030.

Essentially, countries fall into four groups:

- The first group are those countries which are likely to have surplus AEAs in 2030. Their expected NETS emissions will be below their ESR targets. These are mainly Central and East European countries but also include three Mediterranean countries, Greece, Portugal and Spain.

- The second group are those countries where the distance to target falls within a 10% range and thus will require some additional effort. This group of countries includes the UK (which is just 4.3% above target in 2030 in the Reference Scenario) and Italy (which would be 9.8% above target).

- The third group of countries are those where the distance to target is greater than 10% and where significant additional efforts will be required over the next commitment period. This group ranges from Austria (with a 2030 ‘distance to target’ of 11.7%) to Luxembourg (with a ‘distance to target’ of 54.2% in 2030), These are marked in colour in the table above. However, from the agricultural perspective, this group can be divided into two. For Luxembourg, Austria, Belgium and Germany, the share of their NETS emissions coming from agriculture is relatively low in 2030, less than 20%. These countries could probably hit their NETS target in 2030 by taking additional measures in the building, transport and waste sectors without doing much agricultural mitigation.

- This then leaves a fourth group consisting of Denmark, France, Ireland and the Netherlands. These all have ‘distances to target’ greater than 10% and shares of agricultural emissions greater than 20% of total NETS emissions in 2030. The challenges for agricultural mitigation in Ireland and Denmark are particularly marked. Ireland has a ‘distance to target’ in 2030 of 15.1% and an agricultural share in NETS emissions in 2030 of 49.0%. Denmark has a similar distance to target of 16.2% and an agricultural share in NETS emissions in 2030 of 36%. France and the Netherlands have lower shares of agriculture in total emissions but a higher expected ‘distance to target’. In these four countries, agricultural mitigation will have a play a central role if the 2030 NETS targets are to be met by domestic action alone.

In evaluating this conclusion, it is very important to highlight some of the key uncertainties behind the table above.

- The ‘distances to target’ have been calculated assuming full use of permitted flexibilities. As noted above, some member states may decide not to use all of their allocations. For these countries, the ‘distance to target’ would then be larger than shown in the table.

- The 2016 Reference Scenario assumes full and successful implementation of all existing policy measures and that member states will meet their climate and energy targets in 2020. Even if this latter assumption is likely for the EU as a whole, individual member states may not be on track in 2020. This would result in a larger ‘distance to target’ in 2030 for these member states, ceteris paribus, than assumed in the Reference Scenario. When the European Environment Agency Trends and Projections in Europe 2016 report is published next month, it will be possible to compare the individual member state 2015 figures in the Reference Scenario with actual inventory figures in that year to identify countries which are not following the Reference Scenario trend.

- “[The Reference Scenario] projected 2030 trends see overall higher reductions than member states projections. Member states themselves in aggregate see emissions only reduce by 18% in their GHG projections submitted in 2015 that look at the impact of existing measures. This would result in an aggregate gap in 2030 as large as 12 percentage points” (p. 17-18).

- This is a significant difference when estimating the ‘distance to target’ in 2030. The figure below, taken from the ESR impact assessment, illustrates the significance of these different scenarios. The impact assessment has a box (Box 2, p. 18) which attempts to explain the discrepancies.

- Focusing on a single year over the period 2021-2030 can give a misleading impression of the effort required given the possibility to bank surplus allowances in earlier years under the flexibility provisions in the ESR. In the ESR impact assessment, the division between surplus and deficit countries is based on an estimate of the cumulative figures over the commitment period. On the other hand, to the extent that a member state does not meet its 2030 target it builds up difficulties to achieve more stringent targets in subsequent periods.

- The assumption is made that there is no carryover of surplus AEAs from the 2013-2020 commitment period into the 2021-2030 period. The ESR impact assessment notes that EEA estimates based on member state projections show an expected surplus of AEAs to 2020 which amount to much more than the total emission reductions needed over the period 2021-2030 additional to the Reference Scenario. Any transfer between the periods would reduce the incentives for long-term mitigationaction. However, the current Effort Sharing Directive does not foresee that any overachievements in the current period could be used for meeting national targets during the next commitment period, and neither do the European Council conclusions.

Conclusions

On the basis of the Commission’s modelling which seeks the most cost-effective mitigation options to meet the EU’s 2030 climate targets it seems that EU agriculture would not be asked to make additional mitigation efforts beyond policies currently in place in the period to 2030.

Some caveats to this conclusion can be quickly noted. First, farmers will still be expected to reduce the emissions intensity of their production in line with the trend foreseen in the 2016 Reference Scenario even if they are not asked to go beyond this.

This is not likely to be too demanding. Half of agricultural emissions come from nitrous oxide due to microbial activity in soils, for which the main driver is nitrogen input on agricultural land. Some reduction in the use of mineral fertilisers is foreseen, encouraged by the spread of energy crops on arable land after 2025 that do not require significant fertiliser quantities.

Emissions of the other main greenhouse gas, methane, are expected to remain stable despite increasing animal numbers due to the greater uptake of anaerobic digesters to treat manure as a result of existing incentives in some member states and growing interest in other member states trying to meet their renewable energy targets.

Second, the ‘no-impact-on-agriculture’ conclusion assumes that member states succeed in achieving a high rate of energy efficiency improvement in the other NETS sectors. To the extent that this proves more difficult than expected and member states fall back on the EUCO27 target, agriculture would be expected to take up some of the slack. The ESR impact assessment does not give a specific figure, but it is likely to imply a reduction of around 10%.

Third, the Commission in its optimisation modelling takes an EU-wide view. The picture can look quite different from the perspective of individual member states. The challenge for individual member states is usually measured by the size of the reduction target assigned in the ESR (the required change in emissions in 2030 under the NETS targets relative to each country’s emissions in 2005) (for a ranking of countries on this basis, see this Carbon Action Network briefing). In this post, I suggest the challenge for individual countries is better captured by looking at their ‘distance to target’, that is, the gap between the NETS targets in 2030 and each country’s expected emissions in 2030 under a ‘business as usual’ scenario.

The previous analysis identified a number of member states which are likely to face a demanding ‘distance to target’ in 2030 and in which agricultural emissions make up a significant share of their NETS emissions. The conclusion was that these countries would need to pursue additional agricultural mitigation if they were to meet their NETS targets through domestic action alone.

The Commission analysis, on the other hand, assumes that countries with more demanding ‘distances to target’ will purchase AEA’s from surplus countries when domestic marginal abatement costs are higher than the market price of these allowances. This may make sense in the context of the ‘EU bubble’, in which member states are collectively responsible to meet a common EU target. However, the decision whether to purchase AEA’s or not is more complicated for member states, such as Ireland and Denmark, which have their own unilateral domestic GHG emissions reduction targets.

It would facilitate discussion of these issues if the Commission were to release the more detailed results of its scenario modelling behind the 2016 ESR impact assessment, in particular, showing the expected agricultural mitigation by member state in the EUCO27 and EUCO30 scenarios. The dramatic difference in the implications for additional agricultural mitigation in two studies using the same models and published just two years apart needs to be better explained. It would also be helpful to clarify the apparent inconsistency in the carbon values used for the ESR assessment and the LULUCF assessment in order to better understand the results that are presented. If indeed the extraordinarily low carbon value of €0.05 were used for agriculture (and other sources of non-CO2 emissions) when simulating the most cost-effective mitigation options in the ESR impact assessment, this could be one explanation why so little additional agricultural mitigation is required in those scenarios.

Finally, the entire exercise to distribute NETS targets in the ESR was completed before the UK decision to leave the EU. If the UK were to decide to remain part of the ‘EU bubble’ for climate policy purposes (as is the case for Norway and Iceland through the European Economic Area), then the Commission’s proposal would stand (this Centre for European Policy Studies briefing is a helpful guide to the consequences of Brexit for EU climate policy). However, if the UK decides also to exit the ‘EU bubble’ on leaving the EU, the Commission would have to go back to the drawing board in setting NETS targets in the ESR.

Footnote: The contribution required from agriculture in the 2014 impact assessment for the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework was estimated both with and without the introduction of ambitious ‘enabling conditions’ intended to ensure not only the achievement of the 2030 targets but also the EU’s 2050 targets (these ‘enabling conditions’ are referred to as ‘coordinating policies’ in the ESR impact assessment). Although they mainly start to make an impact after 2030, they already start to have an effect before 2030. These ‘enabling conditions’ mainly relate to energy infrastructure development, R&D and innovation, electrification of transport and reduction of energy demand (see Box 2 p. 40 of the Impact Assessment for specific examples). One might assume that, to the extent that the uptake of these enabling conditions is slower than assumed in the modelling, the need for agricultural emission reductions to compensate would be greater. However, the modelling results show no difference up to 2030 in the Impact Assessment Table 40.

A spreadsheet showing the calculations behind the table in this post is available here.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Graphic credit: Clean Technica