The consequences of recent economic trends and the economic crisis for food consumption are graphically highlighted in a recent OECD report Society at a Glance 2014. The report discusses how many families have cut back on essential spending, including on food, compromising their current and future well-being. Reduced spending on food is one of the main causes of food insecurity, a term that describes a situation where inadequate access to food does not allow all members of a household to sustain a healthy lifestyle. According to the OECD:

In the United States, where the incidence of food insecurity is monitored on a regular basis, rates of food insecurity have soared since 2007. While federal food assistance programmes in the United States now support roughly twice as many households as in 2007, the number with inadequate access to food at some time in the year has nonetheless climbed from 13 million (11% of all households) in 2007 to 17.6 million (15%) in 2012. Rates of food insecurity were substantially higher among households with children (20% in 2012) and lone-parent families were particularly affected (35%). Forty-one percent of all food-insecure households received no support through federal food assistance programmes.

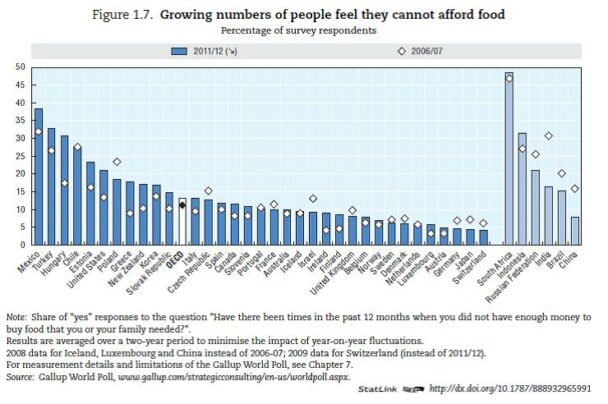

While there are no internationally comparable statistics on food insecurity that are as detailed as those of the United States, some unofficial estimates indicate that growing numbers of families and children suffer from hunger or food insecurity in economically distressed countries…. The Gallup World Poll includes a question on whether respondents feel that they have “enough money to afford food”. Responses confirm that rising numbers of families in OECD countries may have less money to spend on food and a healthy diet. By contrast, while large shares of people in the large emerging economies feel that they cannot afford adequate nutrition, their numbers have mostly declined since 2007.

In the chart above, the countries where household food security has improved are those where the diamond (representing the position in 2006/07) is above the blue column (which represents the position in 2011/12). The countries where improvements have taken place include Poland, the Czech Republic, the UK, Denmark and Germany. But for most EU counties the proportion of households who report that there were times during the previous 12 months when they did not have enough money to buy food has increased, with particularly sharp increases in Hungary, Greece and Ireland, for example.

Further evidence on the growing number of people in high-income countries (HICs) experiencing difficulties in acquiring food is provided in an important paper Banking on Food: The State of Food Banks in High-income Countries published last year by Ugo Gentilini for the UK Centre of Social Protection. This paper is a first attempt to estimate the total number of people supported by food banks in high-income countries. His analysis shows that nearly 60 million people turn annually to food banks in ’rich’ nations – that is, a level similar to the entire population of France or Italy and representing about 7.2 per cent of the HIC population.

EU programmes for the most deprived

The EU’s food distribution programme for the most deprived persons (MDP) in the Union was an important source of provisions for organisations working in direct contact with those people most likely to be experiencing food insecurity.

This food distribution programme expired at the end of 2013. One of the European Parliament’s priorities in the MFF negotiations was to get funding for a continuation of this scheme over the period 2014-2020 (Linda Barry of the Institute for International and European Affairs in Dublin has an excellent post summarising the background to this initiative). In 2014, a new regulation established the Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived (FEAD) to support EU countries’ actions to provide material assistance to the most deprived.

This new fund is not simply an extension of the food distribution programme for the most deprived people. That programme had lost its rationale as a way of disposing of surplus intervention food stocks as these stocks disappeared. Moreover, the European Court of Justice ruled on 13 April 2011, on a case brought by Germany and supported by Sweden, against the monetary allocations granted to member states under the 2009 MDP for purchases of food on the market.

The new FEAD gives member states more flexibility in terms of procuring food to be distributed but also allows the funding to be used for clothing and other essential goods (such as shoes, soap and shampoo) for distribution to the most vulnerable, such as homeless people.

In its MFF conclusions in February 2013, the European Council decided to earmark €2.5bn for the period 2014-2020 for the FEAD. This is not additional money as it is taken from the Structural Funds allocation. In June 2013, it was agreed that member states should have the option of increasing their allocations under the Fund by up to a total of €1bn, so that overall up to €3.5bn may be spent on the Fund in 2014-2020. Member states would be responsible for paying 15% of the costs of their national programmes, with the remaining 85% coming from the Fund.

The issue remains whether such social support schemes should be supported through the EU budget or should remain the responsibility of member states under the subsidiarity principle (my previous blog post sets out the issues; see also the result of the scrutiny of the FEAD legislation by the UK House of Commons). That the scheme is supported so strongly by the Parliament no doubt reflects their desire that Europe should be seen to stand for social solidarity and not only austerity. This debate over the assignment of competences has now been decided, at least for the 2014-2020 period.

Regardless where the funding comes from, it is salutary to be reminded that food insecurity in rich countries, including the EU, is on the increase. Targeted measures to support these vulnerable groups should be prioritised even in a time of economic crisis.

Photo credit: New Europe

This post was written by Alan Matthews

This is indeed a description of the problem from an organisation perspective. What about the analysis of this problem. Haven’t the overheads experienced on British farms contributed to this situation? Has the level playing field of fair competition been compromised by those overheads? Is the British consumer being asked to pay more for food because of the costs to producing food? Meanwhile land is being compromised in Britain by bizarre theories which bring in Sea Eagles, Beaver, and this ‘environmental’ lobby still want more top predators and the removal of food producing livestock. What does anyone think the consequences of those ‘environmental’ theories would do. Please more analysis and less simple description.