One of the more unexpected sections in the Commission Communication The Future of Food and Farming published in November 2017 was the very final section on Migration. This begins “The future CAP must play a larger role in implementing the outcome of the Valetta (sic) Summit, addressing the root causes of migration.” This is, to my knowledge, the first time that an explicit link has been made between the CAP and migration pressures from countries outside the EU in a Commission publication. For example, in the most recent EU Policy Coherence for Development report from 2015, the section on agricultural policy makes no reference to migration.

The root causes of migration

However, 2015 was the year in which more than one million undocumented migrants and refugees arrived in Europe, and several thousands more died in their attempt to cross the Mediterranean. In May of that year, the Commission published its communication A European Agenda on Migration. This referred briefly to the need to address the root causes of irregular migration and forced displacement in third countries.

In November that year, as the migrant crisis escalated, European and African Heads of State and Government met in Valletta to discuss how to address the issue. The summit adopted a political declaration and an action plan which committed as a first priority to address the root causes of irregular migration and forced displacement. Other action areas included enhanced cooperation on legal migration and mobility; reinforced protection of migrants and asylum seekers; prevention of irregular migration, migrant smuggling and trafficking in human beings; and closer cooperation on return, readmission and reintegration.

This was the origin of the focus on “the root causes of migration” in EU development policy (note that while EU documents often refer in shorthand to the root causes of migration, it is irregular migration which is the focus). Since then, “addressing the root causes of migration” has become a central refrain in European development efforts.

For example the European Consensus on Development that was agreed between the three EU institutions Council, Parliament and Commission in 2017 committed that “Through development policy, the EU and its Member States will address the root causes of irregular migration and will, inter alia, contribute to the sustainable integration of migrants in host countries and host communities and help ensure the successful socioeconomic integration of returning migrants in their countries of origin or transit”. (bolding added)

This new focus has had significant budgetary implications. In the Valletta Summit action plan, leaders agreed to establish the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTFA) to “address the root causes of instability, forced displacement and irregular migration and to contribute to better migration management” across the Sahel and Lake Chad, the Horn of Africa and North Africa (bolding added). The Trust Fund for Africa is worth over €3.4 billion. To date, 147 programmes across the three regions have been approved for a total amount of approximately €2.5 billion, although it is unclear how much of this promised money has actually been disbursed.

Another financial initiative announced in 2016 by the Juncker Commission is the European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD). Creation of the EFSD was announced in a June 2016 European Commission communication on the partnership framework for cooperation with third countries under the European agenda on migration. This will have potentially up to €4.1 billion to work with, although €2.6 billion represents resources from two existing blending facilities – the Neighbourhood Investment Facility and the Africa Investment Facility – that will be rolled into the EFSD.

The EFSD framework seeks to establish migration compacts with countries where migrants originate or transit. These tailor-made agreements combine incentives to help partner countries to manage migration effectively, to cooperate on readmission of irregular migrants, and to address root causes of migration. The Fund builds on the Commission’s experience with the use of blended finance where public funding is used to provide a guarantee to attract both private and public sector investment. The aims are to scale up resources for addressing the root causes of migration and to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs.

Role of CAP in addressing root causes of migration

Against this background, the Commission’s CAP Communication suggests that the CAP can also contribute to addressing “the root causes of migration”. Six specific actions are suggested:

• Sharing knowledge and know-how gained from CAP-supported projects to develop employment opportunities and revenue-generating activities in regions of origin and transit of migrants, including possible projects for training young farmers – with the involvement of European farmers’ organisations.

• Developing EU-Africa Union exchange schemes for young farmers along the lines of ERASMUS+.

• Deepening cooperation on agricultural research and innovation through the relevant EU policies and instruments.

• Enhanced strategic policy cooperation and dialogue with the Africa Union on issues related to agriculture and rural development so as to help the region develop its agri-food economy.

• Offering opportunities for seasonal workers in agriculture.

• Using EU rural development programmes to help settle and integrate legal migrants, refugees in particular, into rural communities, building on the experience of Community-Led Local Development/LEADER projects.

These are all worthwhile projects to pursue. For example, European agriculture has a growing dependence on migrant workers from outside the EU. According to official data, immigrants constitute today over one-third of the salaried agricultural workforce in southern EU countries (data from this policy brief by Michelle Nori from the Migration Policy Centre at the European University Institute in Florence).

However, only the proposal to use CAP resources to help integrate legal migrants into rural communities would seem to fall under the specific competence of the CAP. The other projects seem to involve areas of competence within the Commission other than agriculture, or even refer to competences reserved for Member States such as the admission of non-EU nationals as seasonal workers.

Currently, a very small amount (around €8 million annually) is reserved in the CAP budget (Chapter 05 06 International aspects of the Agriculture and Rural Policy Area) for international engagements. This is spent entirely on EU participation in various international agricultural agreements and organisations. It is not clear if the CAP Communication intends that some of these proposed new initiatives would be funded from the CAP budget or not.

The Task Force for Rural Africa

DG AGRI and Commissioner Hogan is giving a push to these proposals by announcing, in cooperation with DG DEVCO, the creation of a Task Force for Rural Africa. The overall objective of the Africa Task Force is to look at job-creating economic development in agriculture, agri-business and agro-industries, and to advise on priorities and next steps in cooperation with Africa. The Task Force will work in close cooperation with the African Union and will complete its work by January 2019.

Commissioner Hogan, in addressing the joint DEVE/AGRI hearing on “The Impact of the CAP on Developing Countries” on 27th February 2018 in the European Parliament, underlined that the intention is to move beyond traditional forms of development co-operation to focus on “targeting policy support, fostering investments in rural areas and supporting agro-industries in Africa, with the involvement of the private sector”.

We are re-thinking our traditional development cooperation models and going beyond our development assistance and trade relations to focus more on ‘investments and policy dialogue’. We need to address the issues that really matters in relation to underdevelopment in African agriculture.

There are those who argue that the CAP itself continues to contribute to underdevelopment in African agriculture. For examples of this point of view, see this blog post by two African academics, or the remarks of Kofi Annan when invited to speak at the Forum for the Future of Africa in Brussels last year. Development NGOs sometimes claim that there is an inherent conflict of interest between the export interests of European agribusiness firms and the concern of weak agriculture-based economies in the developing world to increase their self-sufficiency in food.

The existence any longer of a link between the CAP and underdevelopment in African agriculture was strongly rejected by Commissioner Hogan in his address to the joint DEVE/AGRI Hearing on “The Impact of the CAP on Developing Countries“.

We need to address the issues that really matters in relation to underdevelopment in African agriculture. Let me repeat very clearly that the CAP is not one of these issues! It is in fact about a long period of underinvestment in this sector in Africa; and it is about structural shortcomings, which EU assistance is trying to help overcome.” (bolding in the original)

Broadly, I agree with the Commissioner’s view that the CAP now has very limited distorting effects on world markets (see my 2014 working paper An updated look at the impact of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy on developing countries, and also the study prepared by Maria Blanco for the European Parliament The impact of the Common Agricultural Policy on developing countries). There are obvious exceptions, such as the growing role of coupled support payments. High tariffs continue to protect EU production in certain sectors, such as red meats, but extensive preferences for low-income developing countries muddy the waters when assessing their development impacts.

However, development NGOs have gone on to raise a series of other issues in which they claim that EU agricultural production (and implicitly the CAP) is complicit in a variety of ills in developing countries: its virtual land and water footprints; the impetus to deforestation; land grabbing; and adverse effects on the nutrition status of developing countries. While in my view the jury is still out on the extent to which these ill-effects can reasonably be attributed to the CAP, these criticisms raise important issues that should be addressed in any debate on the CAP and migration.

Can development reduce migration?

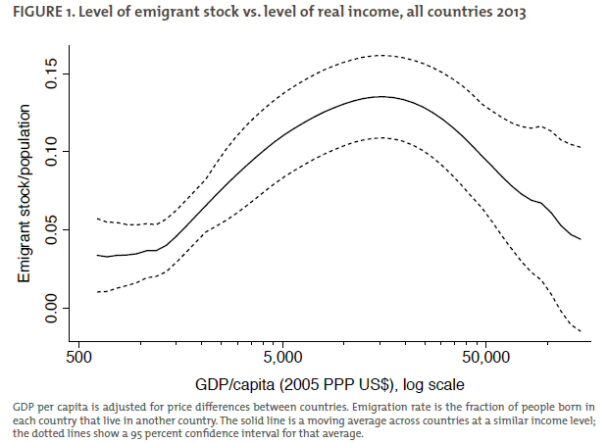

Another important question is whether successfully addressing “the root causes of migration”, which are generally seen as the same as those responsible for poverty, will actually reduce irregular migration flows. Academic research suggests that a negative correlation between migration and development is only observed when countries reach a relatively high income level. At lower income levels, migration and development are positively correlated. This is known as the ‘migration hump’. The inverted U-shaped relationship is seen clearly in the figure below, taken from a recent policy brief by Michael Clemens and Hannah Postel at the Centre of Global Development (the longer and more technical paper is available here). For comparison, Mexico today has just passed the GDP per capita level (measured in PPP dollars) where further economic development will tend to reduce migration flows.

These authors highlight two reasons why development will lead to increased levels of migration at lower income levels, based on the investment and insurance motives for migration.

As an investment, families exchange up-front costs for large but delayed income gains from overseas work. This suggests a complex relationship between migration and economic development. Greater economic opportunity at home may decrease the incentive to invest in working abroad, but may also make such an investment more feasible. Emigration from middle-income countries is typically much higher than from poor countries; countries earning $8,000-10,000 per capita annually have three times more migrants as countries earning $2,000 or less.

Poor families also use migration as a form of insurance.

It helps them to diversify income across members of the household, making the family less vulnerable to shocks like job loss or sudden sickness. Migration also helps diversify income over time, reducing the risk of dire lean periods for the whole household…. The relationship between development and migration is again complex in this setting. More stable economies can reduce the need to insure against shocks, but as aspirations rise, so can the need for insurance.

Their conclusion is that development does more to encourage migration in poorer countries than to stem it. Indeed, in another working paper Impact of EU’s agricultural and fisheries policies on the migration of third country nationals to the EU one of the few regularities I could find was that source countries for ‘push’ economic migrants tend to be middle-income rather than least-developed countries.

These simple models based on economic motives for migration alone are powerful, but probably too narrow. As this German Development Institute brief More development – more migration? notes, the migration hump differs across countries. The age structure of the population, individual perceptions of security, the degree of inequality and the size of the existing diaspora all play a role in the migration decision. This brief warns that “reducing development cooperation in order to prevent irregular migration could only succeed in achieving the opposite”.

Conclusions

My purpose in drawing attention to the evidence that development, including agricultural development, in low-income countries is likely to increase the propensity to migrate is not, of course, to argue in favour of keeping poor countries poor. Improving economic and non-economic welfare for the populations in these countries, and particularly those living in rural areas, should remain an absolute priority. The migration consequences of successful economic development should then be addressed by other instruments in the European Agenda on Migration.

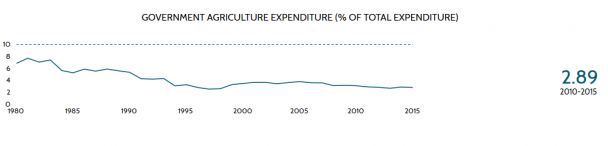

It would be encouraging if the proposed dialogue on agricultural policy support with African Union countries could help to change policy priorities on that continent, but I am sceptical. It is now fifteen years since the African Union member states in 2003 committed to the objectives of the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) including targets of 6% annual growth in agricultural GDP, and an allocation of at least 10% of public expenditures to the agricultural sector. African governments recommitted to these targets in the Malabo Declaration on African agriculture and CAADP in 2014.

But these declarations have remained empty words. Public expenditure on agriculture (in constant 2010 US$) for Africa as a whole amounted to $940 million in 2003 and $930 million in 2016 (ReSAKKS Annual Trends and Outlook Report 2016). The share of agriculture expenditure in total public expenditure has fallen well short of the CAADP target of 10 percent budget share. The share grew from an annual average of 3.2 percent in 1995–2003 to 3.5 percent in 2003–2008 and has declined to 3.0 percent in 2008–2016 (see chart below).

Source: ReSAKSS

A single quantitative indicator on its own does not capture the complexity of agricultural spending. It says nothing about its quality or relevance. Many African governments have favoured expenditure on input subsidies rather than investing in the public goods such as agricultural research, certified seed systems, agricultural extension, animal health and rural infrastructure which are the necessary foundations for long-run sustainable agricultural growth. So even the small share of public spending devoted to agriculture is not always wisely used.

As over half (55%) of employment in Sub-Saharan Africa is in agriculture (for the Middle East and North Africa the share is lower at 21%), this failure of African governments to invest in their own agriculture is the principal cause of the lack of dynamism in that sector. It is a failure that European development NGOs too rarely address, while devoting resources to campaigning for change in relatively trivial aspects of European agricultural policy from a development perspective.

Persuading African governments to invest sensibly in their own agricultural development may not do much to stem the flow of migrants in the future, but it would do wonders for the more than half of Africa’s labour force that rely on agriculture for their livelihoods.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Update 5 April 2018: I have added a sentence to qualify my broad agreement that the CAP now has limited distorting effects on world markets.

Additional reading: Those interested in the link between hunger and migration more generally will find this policy brief What is the link between hunger and migration? by David Laborde, Livia Bizikova, Tess Lallemant and Carin Smaller of interest. The authors conclude that economic growth was the strongest factor influencing migration, and that there was no discernible relationship between hunger levels and migration.

Photo credit: World Bank / Scott Wallace via Flickr, used under Creative Commons licence