Problems in the generational transfer of farms have been a focus of EU agricultural structures policy since the 1990s and in individual member states for an even longer period. Europe’s farmers are getting older, and the shortage of ‘new blood’ entering the industry is frequently seen as a problem requiring a policy response to correct.

The ageing of the agricultural population results from a combination of two things: a reduced rate of entry by new young recruits, and a reduced rate of retirement or exit by older farmers. This is taking place in the context of a long term reduction in the agricultural labour force in EU countries.

There is no doubt that the average age of farmers is increasing steadily. Unfortunately, the age of farm holder tabulations from the 2010 Agricultural Census have not yet been released by Eurostat, so the latest data we have are still from 2007. In 2007, 31% of holders of agricultural holdings in the EU-15 were 65 or older (28% in 1997 and 24% in 1990). Note that all the percentages in this post refer to the EU-15 as age distribution figures for the new member states are not available for the longer time period.

The proportion of farm holders over 55 has remained fairly constant over this period (54% in 1990, 55% in 1997 and 55% in 2007). However, while just 8% of holders were younger than 35 in 1990 and 1997, this proportion had dropped to 5% by 2007. Trends over the longer period for the EU-15 are shown in Figure 1.

Note: The figures are not fully comparable over the period. Figures for Belgium are not available for 1990 and for Austria, Finland and Sweden for 1990 and 1993. Germany is only included (including the former Eastern Germany) from 2000 on. Around 5% of holdings were unassigned in 2000 and these have been excluded in calculating the proportions. Source: Eurostat ef_ov_kvage

Note: The figures are not fully comparable over the period. Figures for Belgium are not available for 1990 and for Austria, Finland and Sweden for 1990 and 1993. Germany is only included (including the former Eastern Germany) from 2000 on. Around 5% of holdings were unassigned in 2000 and these have been excluded in calculating the proportions. Source: Eurostat ef_ov_kvage

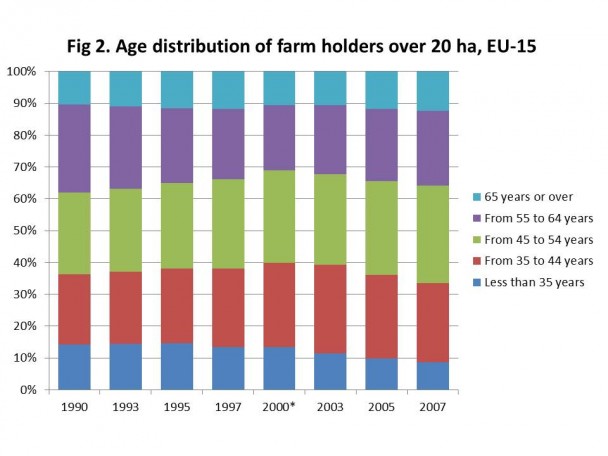

It is known that younger farmers are more likely to be found on larger farms where the prospects for making a viable living are greater. Figure 2 shows the age distribution of holders on farms over 20 ha in the EU-15 (I have chosen 20 ha as an arbitrary threshold to make a rough distinction between smaller and larger farms). However, while the absolute figures are somewhat better, the trends are the same.

Farm holders over 65 made up 10% of total farm holders on farms over 20 ha in the EU-15 in 1990 and 13% in 2007, although farm holders over 55 on these larger farms have maintained a roughly constant share (37% in 1990, 34% in 1997 and 36% in 2007). Farm holders under 35 made up 14% of the total in 1990, 13% in 1997 and 9% in 2007).

Note: The figures are not fully comparable over the period. Figures for Belgium are not available for 1990 and for Austria, Finland and Sweden for 1990 and 1993. Germany is only included (including the former Eastern Germany) from 2000 on. Around 5% of holdings were unassigned in 2000 and these have been excluded in calculating the proportions. Source: Eurostat ef_ov_kvage

Note: The figures are not fully comparable over the period. Figures for Belgium are not available for 1990 and for Austria, Finland and Sweden for 1990 and 1993. Germany is only included (including the former Eastern Germany) from 2000 on. Around 5% of holdings were unassigned in 2000 and these have been excluded in calculating the proportions. Source: Eurostat ef_ov_kvage

A feature of the age cohorts is that, in each decade, the numbers of farm holders in the 45-54 age group is greater than in the 35-44 age group in the previous decade, indicating that there are significantly more net entrants to farming in the older age group than net exits. These may be relatives assisting on farms who take over the farm management on the death of the previous holder, but they may also be family members who now live and work in urban areas but who decide to hold on to the family holding either as a part-time farm or as a second home after the death of their parents. There may also be small numbers of ‘hobby farmers’ with an urban background with sufficient means to acquire a farm as a rural residence included in these figures particularly in the countries of northern Europe. It is only in the 55-64 age cohort that exits begin to (just about) exceed new entrants.

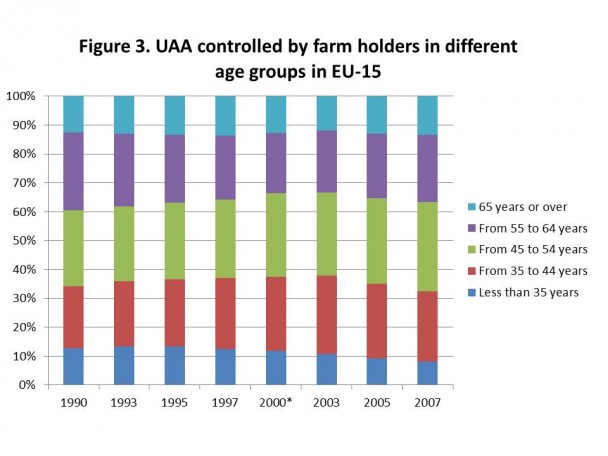

Another way of looking at the figures is to ask whether the area of land controlled by older farmers is increasing. Evidence from the US for the period 1988 to 1999 suggested that the share of farm assets controlled by the over-65’s increased significantly (from 17% to 34%, see Gale 2003). This does not appear to be the case in the EU-15 where the share of UAA farmed by the over-65’s was 12% in 1990, 14% in 1997 and 14% in 2007 (the corresponding shares for the over-55’s are 39%, 36% and 37% respectively). On the other hand, the share of land farmed by the under-35’s has fallen from 13% in 1990 and 13% in 1997 to 8% in 2007 (see Figure 3).

Note: The figures are not fully comparable over the period. Figures for Belgium are not available for 1990 and for Austria, Finland and Sweden for 1990 and 1993. Germany is only included (including the former Eastern Germany) from 2000 on. Around 5% of holdings were unassigned in 2000 and these have been excluded in calculating the proportions. Source: Eurostat ef_ov_kvage

Note: The figures are not fully comparable over the period. Figures for Belgium are not available for 1990 and for Austria, Finland and Sweden for 1990 and 1993. Germany is only included (including the former Eastern Germany) from 2000 on. Around 5% of holdings were unassigned in 2000 and these have been excluded in calculating the proportions. Source: Eurostat ef_ov_kvage

These trends can be explained by two main fundamental forces. First, the relatively low returns in farming compared to other occupations, combined with the disamenities of living in the more remote rural areas, mean that a career in farming has not been attractive to the younger generation. Second, farmers like everyone else are living longer. And because there are fewer exit opportunities for older farmers for whom their farm is also their home, the fact that they are living longer means that the transfer to the next generation is now taking place later than it did before.

Vision statements, commission reports and scenario studies in various EU countries lament the ageing of EU farm holders and call for policy interventions to counter this trend (see, for example, the 2008 European Parliament resolution on The future for young farmers under the ongoing reform of the CAP). However, the evidence presented above suggests that what we observe is a slow upward shift in the age distribution which can be explained by general social trends (longer schooling periods and longer longevity) rather than any specific worsening of the generational transfer problem in agriculture as such.

One of the innovations in the Commission’s legislative proposals for the CAP post-2013 is an overhaul of the scheme of installation aid for young farmers and the proposed introduction of a compulsory additional direct payment in Pillar 1 for young farmers receiving the basic payment. However, independent analyses as well as evaluations of previous versions of young farmer schemes suggest that these are hard to justify on a value for money basis. Contrary to conventional wisdom, age is not necessarily related in a negative way to higher productivity.

© Photograph copyright Richard Law and licensed for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence.

Europe's common agricultural policy is broken – let's fix it!