The European Parliament (EP)’s agricultural committee adopted its Opinions on the three CAP-related legal proposals earlier this month. However, lack of time during this Parliamentary session before elections take place to the EP at the end of May means that the Parliament itself will not vote on these Opinions until after the new Parliament reconvenes in July.

While the outgoing committee would like to see the new Parliament use its Opinions as the starting point for its plenary voting, there is no guarantee that this will be the case. The composition of the political groups in the new Parliament may be very different to what has existed in the current Parliament. In this post, I look at projections of EP election results in May and what this might mean for the outcome for the CAP reform legal proposals.

Political groups and political parties

There is an important distinction between political groups in the EP and European political parties. EP political groups bring together individual MEPs with the same political leanings. European political parties are transnational parties with national parties as members.

There are currently eight political groups in the European Parliament. Parties and members elected to the Parliament form political groups because this is a way to gain influence (for example, in the selection of Committee chairs, as rapporteurs of Committee opinions or to be able to propose amendments to reports that will be voted on) as well as resources. Political groups have their own organisation including a bureau and secretariat. Although political groups try to coordinate their voting, no member is obliged to follow the group recommendation. To form a political group, a minimum of 25 MEPs, elected from at least one quarter (currently seven) of the EU’s Member States is required.

European political parties are distinct from Parliamentary political groups. European political parties are recognised in the Lisbon Treaty and played a significant role in the 2014 EP elections in the spitzenkandidat process. While most of the national parties represented within a political group are also members of the corresponding political party at the European level, some political groups are made up of more than one European political party, some may also include non-attached MEPs and some political groups may not contain a European political party.

The relationship between political groups and political parties in the 2014 EP is shown in the table below.

European political parties are eligible for funding from the EP if they are registered as such with the independent Authority for European Political Parties and Political Foundations which was established in 2016. To be eligible for registration, a political party must be represented in at least one quarter of the Member States (seven) by MEPs, or members of national or regional parliaments, or its national member parties must have received, in at least seven Member States, at least three per cent of votes in each Member State at the most recent European elections.

The party or its members must either have participated in elections to the European Parliament or have expressed publicly the intention to participate in the next elections. Only some of these parties have produced European election manifestoes. In other cases, national parties seeking election to the EP may have fraternal links with parties holding similar views in other countries but do not campaign under a common European manifesto. This is especially the case for some of the newer Eurosceptic parties. There are currently 10 European political parties registered with the Authority.

Projected changes in the EP after 2019

There are several sources of polling information on the composition of political groups in the next EP, including the Parliament’s own projections put together by Kantor Public, the Poll of Polls used by, among others, the Financial Times and Politico Europe, and finally Europe Elects. All these sources aggregate national polls to predict the composition of the next EP political groups. Apart from the inherent uncertainty in the polls themselves, not all national parties participating in the elections have declared which group they would intend to align with if elected, which adds to the uncertainty.

Projections until recently have assumed that Brexit will have taken place and that the UK will not participate in the EP elections. In that case, elections would take place to a Parliament with a smaller number of seats, 705 as compared to the current 751. We review here the most recent projections by those sources that have now reinstated the UK seats.

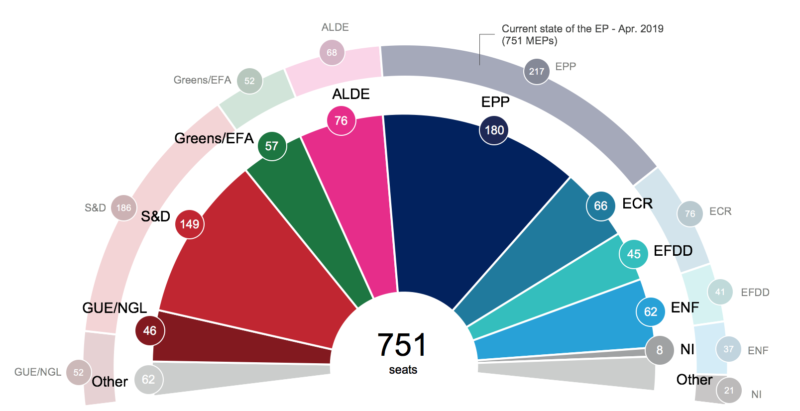

The Parliament has just published its fourth and final set of seat projections on 18 April with a comparison to the current composition of the EP (this is different to the composition following the 2014 election both because of the formation of the ENF in 2015 and defections and recruitment of individual MEPs to other political groups). The EP methodology assigns new national parties that are not currently members of any political group nor a member of a European political party to the ‘other’ category. The webpage also shows the trend in voting intentions over time.

The main message from the projection is that the EPP and S&D will no longer command a majority of seats in the coming Parliament (44%) and would have to rely on the support of the ALDE group (10%) or the Greens (8%) to form a majority. Right-wing Eurosceptic political groups (the ECR, EFDD and ENF) are expected to win almost 170 seats (or just less than one-quarter) in the new assembly. Pro-Europe political groups would still retain an overall majority, but the influence of Eurosceptic groups will be larger, especially if they can avoid the fragmentation they suffer in the current Parliament (see below).

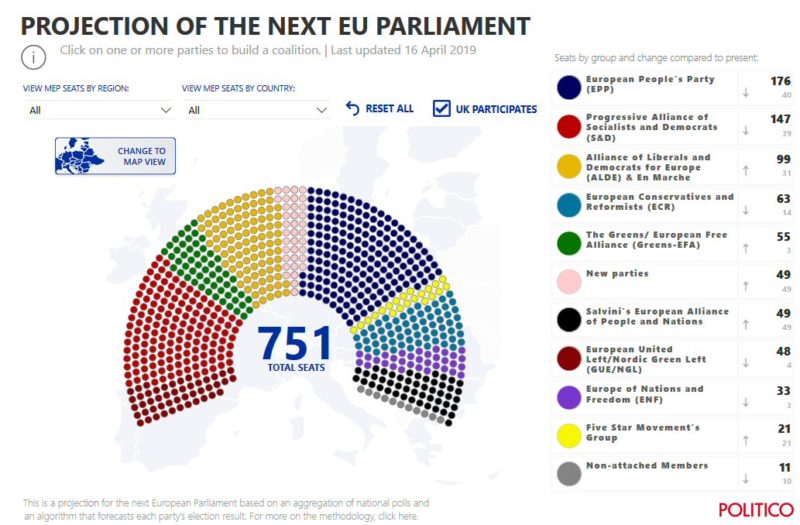

The Politico visualisation of the EP election outcome as of 16 April is shown in the next diagram, while the web page also shows the trends over time. This projection takes account of the announcement by Matteo Salvini of Lega in Italy to form a new political group, the European Alliance of Peoples and Nations (EAPN), which absorbs the current EFDD but before the announcement by the French RN party led by Marine Le Pen, currently a member of the ENF, to join this group). It also shows separately the seats won by the Italian M5S party and includes En Marche with the ALDE group. However, the broad trends remain the same as in the European Parliament projections, even if the projected number of seats for the right-wing Eurosceptic parties seems a little lower.

The published Europe Elect projections still assume Brexit and an EP of 705 seats so are not directly comparable with the projections shown for the other two sources. Their projections are broadly in line and also show the trend over time. Its analysis of the possible permutations among the political groups is particularly interesting, and it also carries an analysis of the implications of Salvini’s initiative to form the new right-wing Eurosceptic grouping EAPN for the groups composed of these parties in the current Parliament.

Polling projections may underestimate support for smaller and newer parties

While the three sources drawing on national polling all project a broadly similar outcome for the composition of the next Parliament, researchers have pointed to a potential source of bias in interpreting polling results produced in this way. In many countries there are no specific polls of voting intentions in the European elections. Instead, it is assumed that voters’ preferences for national elections can also be applied to European elections. There is much evidence that voters treat European elections differently to national elections. For one thing, voter turnout is much lower, but also voters may use the elections to express a protest vote because they believe less is at stake. As a result, in European elections smaller and newer parties tend to perform better than in national ones.

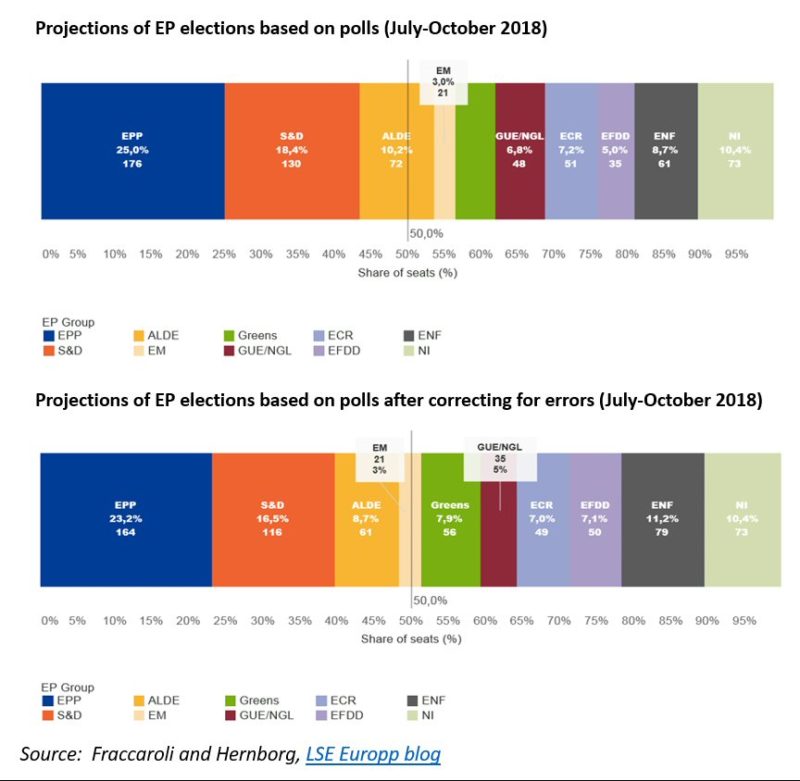

These researchers have adjusted polling data by weighting current polls based on their predicting error in previous elections, at a comparative point in time to the current one. They compute the average error per political group and then assign it to each party’s polls according to its political group membership. Their results in the diagram below confirm overestimation errors for large governing parties such as the EPP, S&D, ECR and ALDE groups, and underestimation errors for small parties such as the Greens and Eurosceptic parties (EFDD and ENF).

Their estimates (based on polling data from the second half of last year) suggest that the support of ALDE alone will not be sufficient to enable the EPP and S&D to reach an overall majority, and would need the support of either Macron’s En Marche (which has agreed to form an alliance with ALDE) or the Greens, which could thus potentially play a greater role in the coming Parliament. While they project greater gains for the right-wing Eurosceptic parties, this would still not be sufficient to allow them to become the dominant force.

The researchers note that their calculated margin of error for political groups is narrowing over time, which they attribute to the increasing availability of polls specific to the European elections, thus minimising the bias they see in using polling data on party preferences in national elections. In addition, of course, polls are at best a survey of preferences at a particular point in time. Underlying preferences may also shift between the date of the polls they used in their research and the election date in May.

Implications of changed EP composition for CAP reform

The agricultural committee in the current Parliament has been dominated by the two main political groups: the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and the centre-left Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D). We have seen that the projections indicate that these two groups will probably lose their joint control of the legislature for the first time in 25 years. At the same time, the number of seats held by Green MEPs and by parties of the Eurosceptic right will increase.

What might the changed composition of the Parliament mean for the CAP reform file? The IEEP has performed a useful service by evaluating the manifestos produced by five European political parties – the EPP, PES, ALDE, Greens and the European Left – against a set of criteria drawn from the UN sustainability agenda and the EU’s environmental action plan. Missing from this list are the views of the Eurosceptic right-wing parties that have not produced European election manifestos.

Right-wing populist parties have two policies in common: anti-immigration (often driven by an explicit Islamophobia) and Euroscepticism. But in many other policy areas, the parties tend to be very diverse. In terms of economic policy, for example, some right-wing Eurosceptic parties take a very neo-liberal and market-oriented approach while others are much more protectionist. On cultural questions, some parties adopt liberal social policies while others are much more traditionalist.

A report published earlier this year by Adelphi, a German independent think tank and consultancy specialising in climate, environment and development, looked specifically at the election programmes and voting behaviour of the 21 strongest right-wing populist parties in Europe as concerns climate change. The report analysed the voting patterns of the three political groups in the EP where these 21 parties sit – ENF, EFDD and ECR – on 13 key energy and climate files since 2015. On every vote the majority of MEPs belonging to these parties voted against the resolutions.

It would be interesting to have a similar analysis of these parties’ views on the environmental issues around food production and land use and their importance relative to more traditional agricultural policy concerns. Anyone familiar with such an analysis might draw it to my attention.

The new Parliament with its different composition will have important decisions to make when it convenes. It must elect the new Commission President based on the candidate(s) put forward by the Council. It will have to decide whether to approve the European Council’s MFF conclusions including the budget provided for the CAP. And it must decide how to proceed on the CAP reform file. It is possible the new Parliament may take a different view on some of the key issues in the current Commission legal proposal. Opinion may shift on the appropriate degree of targeting of direct payments, on the priority to be given to environmental ambition, and on the need for more active market management instruments.

My assessment at this point in time, however, is that the status quo will prevail. The AGRI Committee’s Opinions were promoted by rapporteurs from the EPP, S&D and ALDE political groups. The projections indicate that these three parties will still likely have an overall majority in the new Parliament. If this is the outcome, there is a good chance they will agree to continue in the next Parliament with the positions that they have already adopted in the current one.

If the right-wing Eurosceptic parties succeed in joining together in a unified group after the May elections (not a foregone conclusion when one witnesses the infighting among the pro-Brexit political parties in the UK, for example), this would give them a much stronger platform to influence future EU appointments and CAP legislation. In the current Parliament they are fragmented into three political groups which has limited the impact they have made. The mainstream parties also built a ‘cordon sanitaire’ around the right-wing parties by excluding them from parliamentary work.

If the Salvini EANP grouping manages to unite the various right-wing Eurosceptic parties under one umbrella this would no longer be possible. These parties will have more access to information and leverage on decision-making through appointing shadow rapporteurs for committees and through their participation in the parliament’s Conference of Presidents. Even if this does not immediately affect the CAP reform file, it will certainly influence the future work of the AGRI Committee in the next Parliament.

Conclusions

It is not only the Parliament that will change. There will also likely be a new Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development from November. Commissioners are appointed by their national governments. With the greater number of Eurosceptic and nationalist parties in power, this will also be reflected in the composition of the new Commission. The new Commissioner may not be as committed as is the current Commissioner to the need to modernise the CAP to better tackle environmental and climate challenges, even if green groups argue that his proposals still do not go far enough.

On balance, it seems that the three political groups behind the AGRI Committee Opinions on the CAP post 2020 legal proposal will continue to have a majority in the new Parliament. While personalities will change, this may be sufficient to ensure that the new Parliament votes in plenary on the basis of these Opinions.

However, the political trends discussed in this post suggest there could be less support for using the CAP to address environmental and climate challenges in the next Parliament. But it is important to recall that the proposals respond to a growing demand from public opinion across Europe to address the challenges of climate stabilisation and to move food production on to a more sustainable development path. It remains open how the new Parliament will respond to these challenges.

Update 13 May 2019. Another seat projection was completed in April 2019 by a group of political scientists for the European Council on Foreign Relations.

This post was written by Alan Matthews