The withdrawal of the UK from the EU (Brexit) will have a negative economic effect both for the UK but also for the EU. The size of these negative effects will depend, in part, on the nature of the future trade relationship that may be negotiated if the Article 50 negotiations on withdrawal are successfully concluded and, in part, on the nature of the transition arrangements, if any, that may be agreed to bridge the period between Brexit Day and the entry into force of a future trade agreement.

The UK government’s objective for the long-term relationship remains that set out in the Lancaster House speech last January, namely, withdrawal from the Single Market and from any type of customs union with the EU, but agreement on an ambitious free trade agreement. However, the UK government has yet to spell out what exactly an ambitious free trade agreement might entail.

There seems also to be a growing acceptance by the UK government that the original British bravado that both the withdrawal negotiations and the future relationship could be done and dusted within a two-year period as part of the Article 50 negotiations was just a nonsense (even if the Foreign Minister Boris Johnson seems not yet to have got the message). However, conflicting signals about what transitional arrangements might be acceptable continue to be sent by individual Ministers.

Given this confusion, and the difficulties in the way of a successful conclusion to the Article 50 negotiations, the possibility that we could end up in a situation where the UK and the EU trade on WTO terms without a trade agreement after Brexit Day is not a negligible one. This would mean the re-introduction of customs clearance checks at borders, the loss of automatic access to each other’s markets for a host of goods and service providers because compliance with regulatory standards would no longer be assured, and the re-introduction of tariffs on trade between the two sides. This is what is meant by the ‘cliff-edge’ Brexit outcome.

The consequences of such immediate disruption occurring overnight after Brexit Day are so immense that it seems unimaginable that sane political leaders would allow this to happen. But while at least the need for a transitional agreement is at last being discussed on the UK side of the channel, the EU remains silent on the issue behind the mantra that trade issues (including transitional arrangements) cannot be discussed until sufficient progress is made on the three priority issues highlighted in the European Council guidelines, namely, citizens’ rights, the financial settlement, and the North-South Ireland border.

No doubt clever people on Michel Barnier’s Brexit task force are thinking about this issue. No doubt there is a negotiating logic in dividing the Article 50 negotiations into two phases, and insisting on sufficient progress in the first phase before agreeing to enter into negotiations in the second phase. But insisting on two phases in the negotiations should not preclude the EU from outlining options for the transition period and discussing their feasibility and desirability from an EU perspective.

As I argued in a previous post, given the lack of clarity regarding its negotiating objectives and the resulting tardiness in advancing realistic proposals on the UK side, the EU should not just sit passively by with arms folded and a smirk on its lips. EU interests are also at stake, and therefore the EU needs to take a more active role in trying to shape a Brexit outcome that is least damaging to its interests. As pointed out by a UK commentator, the EU has not yet set out the kind of long-term trading relationship it would like to see with a UK no longer an EU member. Or, in other words, what price the UK must pay for its non-membership of the EU.

Potential tariff differences on Member State trade

Why it is important that we start open and transparent discussions about this long-term relationship among the EU27 is that not all EU27 Member States will share the same interests. A recent paper by Martina Lawless and Edgar Morgenroth of the Economic and Social Research Institute in Dublin looked at one aspect of this question. Their paper focuses solely on the likely implications for trade in goods of the re-introduction of tariffs under a WTO scenario and on the differential impacts of such a scenario on individual EU Member States. The heterogeneity in impacts is a function of differences in trade patterns across countries as well as differences in tariffs and in the responsiveness of demand for different products to price changes.

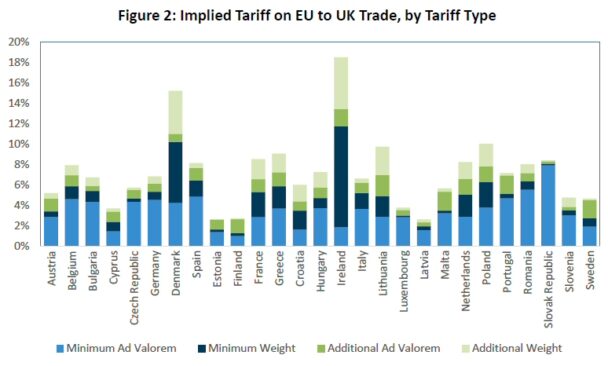

One interesting figure from their paper shows the average tariff faced by exports from individual EU27 countries after Brexit in the ‘cliff-edge’ scenario, assuming that the UK adopts (at least initially) the current EU tariff structure as its applied MFN tariff schedule. The figure is constructed by taking the individual tariffs applied on the over 5,000 goods identified in the EU tariff schedule and weighting these tariffs according to the composition of each country’s exports to the UK (the paper contains a similar figure showing the implied average tariff on UK exports to each individual EU27 Member State after Brexit).

There is some ambiguity over exactly what tariffs are used in this calculation. The authors in the paper refer to minimum and maximum tariffs “registered with the WTO” but do not provide a source for this information. Bound tariffs (maximum tariffs) are included as part of each country’s schedules of commitments in the WTO. The WTO also collects information on applied MFN tariffs in its tariff database which may be lower. However, the most recent WTO Trade Policy Review of the EU notes: “Applied rates are generally identical to the WTO bindings” (p. 48), so I find it difficult to understand the difference between minimum and maximum tariffs shown in this figure. The authors state that in their subsequent analysis they assume it would be the minimum tariffs that would apply to EU-UK trade.

The authors calculate that the application of WTO tariff rates on exports from the UK to the EU (not shown) would result in an average (minimum) tariff of 4.1%. The average minimum tariff imposed by the UK on goods coming from the EU would be 5.7%, but with great variation between Member States. Tariffs imposed on imports from Denmark and Ireland would be over 10% (with the maximum values potentially as high as 18% in the case of Ireland), mainly because a greater proportion of their exports to the UK consist of agri-food products where tariffs are higher than the average for all goods.

The authors convert these data into a simple measure of exposure to the re-introduction of tariffs by calculating how the variation in tariff rates across countries translates into different shares of tariff revenues owed to the UK and due from the UK and how these compare to the shares of each country in total EU-UK trade. In the absence of variation of tariffs across sectors, the shares of trade and tariffs should be the same. Ireland in particular stands out in terms of tariff exposure on the UK’s imports from the EU – it makes up 5% of the UK’s imports but would be charged close to 20 % of the total EU tariff. Germany, on the other hand, would be liable for just under 18% of the tariff owed to the UK, despite accounting for over 28% of the trade flows. These differences reflect the very different tariff rates applied to products and the different product composition of imports and exports from and to the UK. A table in their paper gives the equivalent shares of trade and tariff revenues for each individual EU country.

Trade implications of tariff-induced price increases

In a final step, the authors calculate what the tariff-induced price increases would do to trade values across all of the products being exported from the UK to the EU countries and vice versa. The total trade impact is a combination of the size of the price increase caused by the tariff and the sensitivity of each product to price changes. The latter is given by the price elasticity of import demand for each sector.

Ideally, one would like to have separate estimates of price responsiveness for each of the 5,000 individual products, but estimates are only available (from a study by Imbs and Mejean) at the ISIC 2-digit sector level. This means that the same price elasticity of import demand figure is used for all agri-food products, for all beverage products, for all textile products, and so on.

The methodology to derive the impact of re-introducing tariffs on trade flows is simple. Assuming that the new tariffs are fully reflected in an increase in the consumer price, they multiply the percentage increase in consumer prices by the sector-level import demand elasticities to derive the projected percentage change in each trade flow. By multiplying these percentage changes by the current value of each trade flow and summing over all trade flows, they calculate the expected reduction in trade flows in a WTO scenario for the UK and each EU Member State.

Combining the price increases and elasticity estimates generates a fall in EU to UK trade by 30% and a 22% reduction in UK to EU trade if median elasticity estimates are used. The figure below shows the extent to which the trade reductions would impact on each of the EU members. The authors summarise the results as follows:

“The variation in the effect on exports to the UK is greater than that of imports from the UK given that the structure of imports from the UK varies rather less across countries than does the composition of each country’s exports to the UK. Countries such as Cyprus, Estonia, Finland and Latvia would be relatively modestly affected by the implementation of WTO tariffs, seeing their exports to the UK fall by between 6% and 11%. Countries that would see export reductions to the UK well in excess of the average effect of a 30% fall are Denmark, Spain and Romania, who would all see reductions in the order of 40%, and Slovakia which would be the most severely affected in terms of its exports to the UK project to decline by 59%.

The high tariff rates associated with some products – primarily food and clothing – when combined with the price elasticity response would result under our calculations in a number of product lines ceasing to be traded altogether. … Around 10% of the over 4000 products exported by the UK to the EU would be dropped as a result of the price increase induced by WTO level tariffs…. The impact on product lines exported again varies more for exports from EU countries to the UK… For example, Cyprus experiences the largest decrease in number of products exported (31%) although its total trade reduction was a relatively modest 11%. On the other end of the scale, Estonia remains one of the least exposed countries by this metric as well as having one of the lowest falls in the trade value estimates. Other countries that would see a substantial percentage of products likely to no longer be viable as exports to the UK are Malta, Bulgaria and Latvia”.

In addition to showing the expected trade impacts by country, the authors show the expected impacts by sector. The following diagram shows the expected impacts by sector for EU exports to the UK and for UK exports to the EU. For ease of presentation, only sectors that would have trade reductions over 20% are shown. The sectors with large trade reductions are those with high tariffs combined with a highly elastic price responsiveness.

The figure shows that the food and clothing sectors would be extremely hard hit by a WTO scenario. The two most affected sectors are both clothes (knitted and non-knitted) where trade both to and from the UK would fall by 99%. However, the next ten most affected sectors are all food-based with falls of 68% for the dairy, eggs and honey sector and up to 95% for sugar and confectionary. Any country within the EU reliant on trade with the UK in these sectors will clearly be disproportionately hit if a WTO scenario is the default trade arrangement

The overall impact on a country’s trade must also take into account how large a share of total exports and imports is accounted for by the UK. A number of countries would see minimal impacts in total trade – Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Slovenia all have reductions of less than half of one per cent. Ireland is the most severely affected when total trade is used, followed by Belgium and Slovakia which also see reductions in excess of 3%. A table in the paper gives the full set of percentage changes for each individual country.

Caveats and conclusions

These estimates are likely to be underestimates of the trade effects of re-introducing tariffs at current EU levels on EU-UK trade. The sectoral import elasticity values calculated by Imb and Mejean refer to aggregate imports in each sector. They are relevant to assessing the likely change in imports if there is a change in relative prices between imports and domestic production. For example, if domestic prices of meat production were to decrease in the UK because it started to allow growth hormones, we would expect UK domestic production to become more competitive and to displace imports. With an estimate of the percentage change in UK costs of production and the Imbs and Mejean value for the import elasticity of demand, we could calculate how much total imports might be expected to fall.

However, the Brexit scenario is a preferential tariff change which affects just some imports into the UK or EU, respectively, but not all. The sectoral import elasticities provide a first estimate of the ‘own price’ trade effect (the ‘own-trade’ effect). In the usual situation where a free trade area is being established, this effect results in trade creation because of preferential tariff liberalisation. But with a preferential tariff change there will also be a ‘cross-price’ trade effect (the ‘cross-trade’ effect). In the usual situation where establishing a free trade area results in preferential tariff liberalisation, the free trade partner imports are not only cheaper relative to domestic production, but also other exporters. Thus the free trade partner will also gain trade at the expense of other exporters. This cross-trade effect adds a trade diversion effect to the initial trade creation effect, magnifying the total increase in trade flows between the free trade partners.

In the case of Brexit, there will be an increase in preferential trade tariffs. Instead of trade creation there will be trade suppression. However, the ‘cross-trade’ effect will continue to magnify this so the total reduction in trade will be even greater than calculated by the method used in the Lawless and Morgenroth paper. Put another way, the percentage changes shown earlier are likely to give a very conservative lower bound estimate of the likely reduction in trade flows between the EU and UK in a WTO scenario following Brexit. This is, of course, even more the case because these estimates only concern the effects of the re-introduction of tariffs and take no account of the impact of Brexit in increasing non-tariff trade costs.

However, the message remains the same. Reverting to a trade situation after Brexit which would see the re-introduction of tariffs on EU-UK trade would likely lead to the elimination or significant reduction in many current trade flows, particularly in the agrifood sector. Whatever about the impacts on UK exporters, this cannot be in the interests of EU exporters to the UK.

Resolving this issue cannot be left to the 11-th hour of the negotiations. Traders will want to know where they stand as they begin to enter into contracts with supermarkets from next summer onwards. Let us hope that the Article 50 negotiations make sufficient progress by October (does anyone believe this will happen?) to allow discussions to start on long-term trade arrangements and transitional periods immediately afterwards.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Photo credit: Delegation of the European Union to the United States

And Britain is doing deals with other nations too. Let the Euros smirk as they will with their files of gobledegook bureaucracy in front of them. Don’t they work as a barrier to effective face to face negotiation- literally.

An interesting article suggesting that there are others besides Ireland who will be impacted under a UK goes WTO scenario. While the EU plays down the impact on MS will there be enough impetus to get the parties to resolve trade issues as quickly as possible?