Last week, the new European Parliament elected in May set out to constitute itself for the coming parliamentary term. The Parliament’s President (David Sassoli, PS&D) and Vice-Presidents were elected for the first half session (2.5 years) and the political groups nominated their members to the various Parliamentary Committees. We now know the names of the 48 AGRI Committee members for the coming period (up from 46 members in the outgoing AGRI Committee), but who are they? And will the new faces make a difference to the Committee’s position on the various files it must address, not least the ongoing debate on the next CAP reform?

The overall election outcome

As is now well known, the European Parliament elections resulted in a loss of seats for the two biggest political groups, the centre-right EPP and the centre-left PS&D, and gains for the liberal group (formerly ALDE, now called Renew Europe, RE), for the Greens and for the eurosceptic parties (for an explanation of the political groups formed at the beginning of the 9th Parliament and the party abbreviations, see this European Parliament news item).

The results for the eurosceptic parties can be analysed in more detail. On the left side of the eurosceptic spectrum, the GUE/NGL group dropped from 52 to 41 seats. In the outgoing Parliament the right eurosceptic wing was made up of the ECR, the EFDD and the ENF and together they accounted for 155 seats. In the new Parliament, the right-wing eurosceptic groups include the I&D and ECR political groups as well as the UK Brexit party and the Italian Five Star Movement (M5S) that have not so far aligned with any political group.

Whether the latter should be included under this heading is debatable. Although a populist and anti-establishment party with a critical position on the EU and the euro, M5S was often closer to the pro-EU groups and especially the Green group in the past Parliament rather than its UKIP allies in the old EFDD political group.

If the Five Star Movement with its 14 MEPs is included as part of the right-wing eurosceptic wing, then its numbers increased from 155 (ECR 77, EFDD 42, ENF 36) to 178 (I&D 73, ECR 62, Brexit Party 29 and M5S 14). A significant factor in this increase was the success of the Brexit Party in the UK. If and when the UK leaves (currently scheduled for October 31 this year), the Brexit Party MEPs along with all 73 UK MEPs will leave. 27 of these seats will be redistributed to the remaining Member States and these additional MEPs have already been elected and we know who they are and their political affiliations. According to an analysis on the LSE EUROPP blog, the main winners will be the EPP (+6) and the I&D group (+4) while the PS&D (-13), Renew Europe (-6), Greens (-3) and GUE/NGL (-1) will lose out.

These umbrella terms may not fully capture the change in the political mood within the Parliament. A party such as Hungary’s Fidesz which is a member of the EPP political group may have more in common with Poland’s Law and Justice party (a member of the ECR) and the Italian Lega (member of I&D) than with the other members of the EPP group.

There will be a pointer to this changing political mood on Wednesday 10 July when the AGRI Committee members meet in their constituent meeting to elect the Chair of the Committee and other members of the bureau for the next 2.5 years. The Parliament’s rules specify that, in the distribution of the posts of Committee Chairs and Vice-Chairs, they should be elected taking account of ‘the need to ensure an overall fair representation of Member States and political views, as well as gender and geographical balance’. To this end, political groups distribute chairs and vice-chairs of parliamentary committees among themselves through an informal agreement using the d’Hondt method (this procedure and the d’Hondt method are well explained in this European Parliament Think Tank briefing) which ensures a proportional distribution of committee posts across all political groups.

However, the proportionality sought with this informal agreement among the political groups has to be confirmed formally in a majority vote for the election of the committee bureaux in the committees’ constituent meetings. Committee Members can still vote down a candidate for the chair or vice-chair from a political group that has been informally ‘assigned’ the post according to the calculation using the d’Hondt method, and choose another one, from either the same or another political group, during the constituent meeting.

According to a Politico Europe story last week, the AGRI Committee chair has been allocated to the I&D political group under this method of divvying up the committee chairs. The name of Gilles Lebreton (RN), a university professor in public law at the University of Le Havre, has been mentioned as its candidate. However, as in the last Parliament, the four pro-EU parties may operate a cordon sanitaire to prevent I&D representatives holding any Committee Chairs (see also this Euractiv story). In this case, the Committee Chair would be up for grabs and Paolo de Castro has been mentioned as a possible alternative name. The outcome of the vote on Wednesday 10th July will indicate whether this threat to veto the appointment of an I&D MEP to the AGRI Committee Chair will materialise or not. Update 12 July 2019: In fact, the cordon sanitaire was enforced and Norbert Lins (EPP) was elected Chair).

Parliamentary experience of members of the AGRI Committee

The most striking fact about the new AGRI Committee is the number of new faces (I have assembled the data used in this post in this spreadsheet – please let me know if you find errors so that I can correct them). Just half of the total (24 of the 48, or 50%) are elected to the European Parliament for the first time in 2019. Furthermore, of those who have previously been MEPs, they were not necessarily members of the AGRI Committee in the previous Parliament. In fact, only 15 of the 48 AGRI Members (31%) were also members of the last AGRI Committee. This proportion would be somewhat higher if substitutes for the AGRI Committee in the previous Parliament are taken into account. While some familiar names from the last Committee are still active including Eric Andrieu (PS&D), Paolo de Castro (PS&D), Herbert Dorfmann (EPP), Martin Häusling (Greens/EFA), Mairead McGuinness (EPP) and Ulrike Müller (RE), the fact that this is overwhelmingly a new Committee will surely have implications for its willingness to take over unchanged the previous Committee’s reports on the CAP reform process, for example.

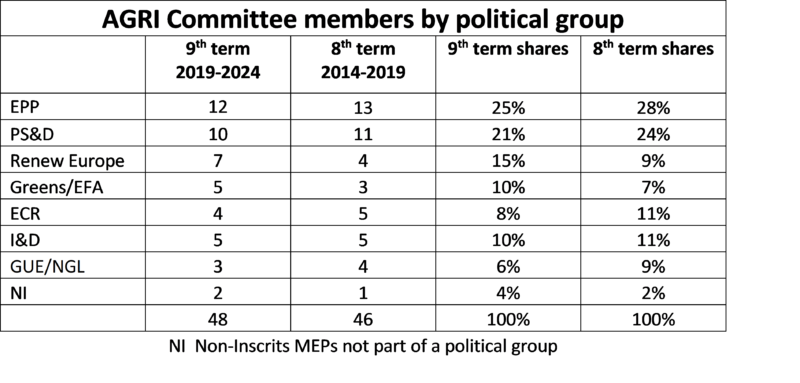

The political composition of the AGRI Committee

The political make-up of the new AGRI Committee compared to the outgoing one is shown in the next table. Unfortunately, the Parliament itself does not seem to maintain an archive of its Committee structure and members from previous parliamentary terms. They are airbrushed from history in true Stalinist style, which is of course deplorable and something that I hope the Parliament will consider rectifying in the future. However, a kind reader has supplied a download of the membership page of the 8th term AGRI Committee before it was deleted.

The changes reflect the overall changes in the composition of the Parliament, as is required by the Parliament’s rules of procedure. Both the EPP and the PS&D have one less seat, while Renew Europe has gone from 4 to 7 and the Greens from 3 to 5. Keeping in mind that there is a small increase in the overall number of seats, the share of these ‘pro-Europe’ parties has increased from 67% to 71% of the total. This may not be a very meaningful aggregate from an agricultural policy perspective as there is no common view on future agricultural policy among these groups, but as observed above, this bloc may play a role in electing the Committee Chair if they implement a cordon sanitaire policy to prevent an I&D representative from taking this position.

Among the populist parties, the left wing populists have gone from 4 to 3 seats while the right-wing populists have gone from 10 to 9, with ECR losing 1 seat and I&D (compared to the old ENF and ENFF groups) holding on to 5 seats. Neither the UK Brexit Party nor the Italian M5S are represented on the AGRI Committee.

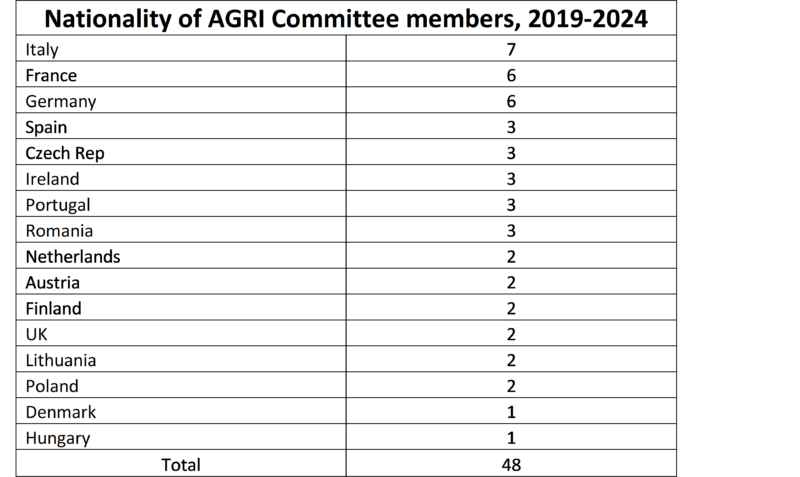

There are sixteen nationalities represented on the AGRI Committee, meaning there are twelve countries that are not represented (see the next table). Italy, France and Spain are the most well-represented countries, while Ireland with 3 members is also disproportionately represented. The Czech Republic, Romania, Poland, Lithuania and Hungary between them have 11 members ensuring that central and eastern countries are well represented. 38% of the members are women, reflecting the overall share of women (40%) in the new Parliament. There is also a broad span over age groups. The eldest member, Mazaly Aguilar (ECR), is 70 and the youngest member, Jérémy Decerle (RE), is 35.

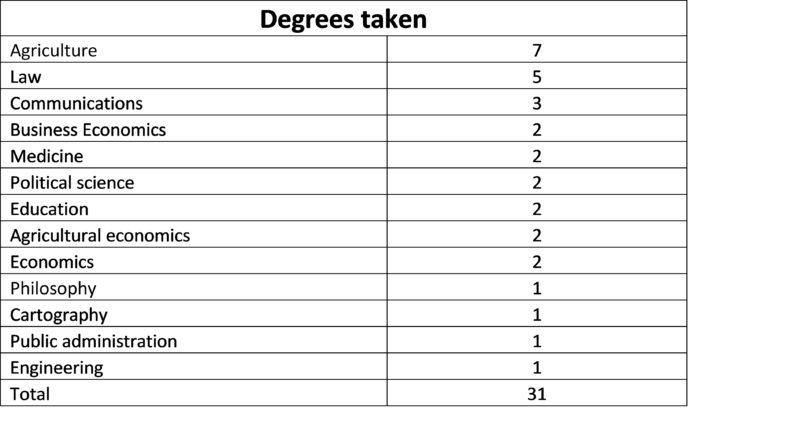

Educational background of AGRI Members

The following table shows the degree subject background of those on the Committee who have obtained a university degree (31 out of the 48) and keep in mind that some of those have taken more than one degree. While those with a degree related to some aspect of agriculture are the single largest group, the list is dominated by those with social science degrees (economics, communications, political science, public administration and philosophy). There are also a number with professional degrees (law, medicine, engineering, cartography, education).

Professional background of AGRI Committee members

The AGRI Committee is often accused of being too close to the interests of its constituency because many members are either farmers themselves or have worked closely with farm organisations. I do not have the data to hand to test whether this characteristic is stronger or weaker with the current Committee. At first glance, however, the farm sector continues to maintain its grip on this Committee.

We can examine the professional background of AGRI members to determine whether they come from a farming background or not. Defining whether one comes from a farming background is not simple. The most obvious indicator is whether one is a farmer or not and thus whether one’s income is affected by decisions taken by the Committee. Ten of the 48 members (21%) are farmers (Biteau, Christensen, Decerle, Häusling, Katainen, Mortler, Müller, Schmiedtbauer, Schreijer-Pierik, Wiener) which is a high proportion. Three of these (Biteau, Häusling and Wiener) are organic farmers (all of whom represent the Green/EFA party) and are likely to take a different view on some agricultural policy issues to the other farmers on the Committee.

One might add to this list those who are married to a farmer and thus whose household income is dependent on farming. The cv details are rarely sufficiently detailed to be definitive but McGuiness would be added to this list on that criterion. Others have been born into farming families but unless they continue to be involved in farming it would not qualify them to belong to this group of those whose income is derived from farming.

The group might be expanded more broadly to include those whose previous income derived from representing farming interests and who thus might be expected to represent the narrow economic interest of farmers. This would include Aguilera (who formerly worked with the Federation of Farmers’ and Stockbreeders’ Cooperatives in Andalusia and the Andalusian Federation of Farming Cooperatives), Dorfmann (former Director of the South Tyrol Farmers’ Union) and Pirbakas (former Head of the Guadeloupe Farmers Union).

One can expand the group even further by including those whose previous professional career involved representing farmers in a political sense or working on agricultural policy issues in a Ministry of Agriculture. The most obvious name here is Ciolos (former Romanian Minister for Agriculture and of course EU Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development), but there are others. Aguilera (already mentioned) is a former Regional Minister for Agriculture in Andalusia, Amaro is a former Secretary of State for Agriculture in Portugal, De Castro is a former Minister for Agriculture in Italy, Hlavácek is a former Deputy Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries in the Czech Ministry of Agriculture, Jurgiel is a former Minister for Agriculture in Poland as is Kalinowski, and Ruissen has been the European Policy Officer at the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality.

Adding all these names together there are at least 21 members (44%) who are either farmers or have represented farming interests at some stage in their professional careers. While it would be wrong to assert that all of these MEPs will necessarily share the same views on agricultural policy, the defence of farm interests will be the natural starting point in any discussions. It is an enviable starting position for any professional interest group to have in a committee whose principal task is to legislate for regulations affecting the sector.

The expertise and calibre of the remaining members of the Committee should not be ignored. The list includes five journalists as well as a number of people who have held Ministerial office apart from Agriculture in their countries (David is a former Czech Minister for Health, Olekas is both a former Minister for Health and for Defence in Lithuania, and Zoido Álvarez is a former Minister for the Interior in Spain).

These are the people who will play a large role in shaping EU agricultural policy over the next five years.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Update 9 July. A previous version of this post used a Wikipedia entry to derive the political group affiliation of AGRI Committee members in the 8th parliamentary term. It proved to be very inaccurate and thanks to the kindness of strangers I obtained the official AGRI Committee list (now inexplicably deleted from the European Parliament website and not archived). The comparison between the political composition of the Committee in the 8th and 9th terms has been rewritten to reflect this. Law has also been classified as a professional degree rather than as part of the social sciences.

Update 12 July 2019. The post was corrected to state that the disappearance of the Brexit Party from the Parliament once Brexit occurs would strengthen rather than weaken the right-wing populist groups once the political affiliation of the new MEPs who would take the redistributed 27 seats is taken into account.

Update 22 July 2019. The proportion of new MEPs in the Committee was corrected to 24, not 26 as previously stated.

Very interesting analysis Alan, many thanks for the spade work undertaken. I would like to use some in the next issue of Practical Farm Ideas http://www.farmideas.co.uk if that’s okay. Attributed of course.

Best wishes, Mike

You are welcome, Mike, I am happy to see the material used and to fix any errors that may have crept in.

Dear Alan, what an interesting analysis. Thank you for putting this together for us!

Very interesting article.

Following from a Romanian perspective, and because you mentioned journalists, 2 of those are from Romania: Carmen Avram, Rare? Bogdan. Mrs. Avram has worked hardly for a media group which is strongly related for many years with the PSD government. During the Presidency, the Romanian ministry of Agriculture hailed once the victory against capping, as a mandatory approach. And, what a coincidence, Mrs. Avram, which is no inch near the agricultural issues (she covered many social-economic issues, but no specialisation on agriculture), also hailed the victory of the Romanian Presidency about the blocking of capping. And Mr. Bogdan which comes from PNL (National Liberal Party) supported conservative views, so it could be also expected that industrial agriculture would have a right supporter in his person. Maybe I am drawing a too simple sketch, but we will see where the votes will go, and how the balance will be kept.