Commissioner Hogan confirmed in his press conference folllowing the publication of the Commission’s proposal on the next Multi-annual Financial Framework that the Commission intends to introduce a cap of €60,000 on the maximum amount of direct payments any holding can receive in the next CAP legislative period. Commission President Juncker is reported as telling the Belgian Parliament earlier this week that “the European Commission will propose a €60,000 limit on individual direct payments to support small farm holdings instead of ‘agricultural factories’”. These statements are misleading and disingenuous, because they ignore what is likely to be the fine-print in the Commission proposal.

The problem is that this proposal is unlikely to achieve its intended objective. The leaked draft of the Commission’s legislative proposals requires Member States to first deduct (the language used is “shall deduct”) the value of salaries paid from the direct payments received before the cap is applied. In the current legislative period, this deduction is optional for Member States when applying the mandatory “at least 5%” reduction on amounts above €150,000 (degressivity), and also for those Member States that make use of the voluntary option to cap payments at some level at €150,000 or above (capping).

Indeed, the leaked draft proposes to extend this loophole to also include the imputed value of own family labour engaged on the farm. Specifically, the draft states that Member States shall also deduct “the equivalent cost of regular and unpaid labour linked to an agricultural activity practiced by persons working on the farm concerned who do not receive a salary (or who receive less remuneration than the amount normally paid for the services rendered) but are rewarded through the economic result of the farm business”.

The effect of these loopholes makes capping meaningless. It follows that the claim of President Juncker and Commissioner Hogan that capping will ensure that direct payments in future will be concentrated on small and medium-sized farms is without foundation and misleading.

The impact of salary deductions from direct payments

The following analysis demonstrates the significance of the labour cost loophole in making capping meaningless. In the current legislative period degressivity and capping of direct payments only applies to the basic payment scheme and the single area payment scheme. In the next legislative period, capping will apply to all direct payments received by a farm.

The average direct payment per ha in the EU at present (claim year 2015) is €256/ha according to the Commission, including the greening payment and all other voluntary elements, and after transfers from Pillar 2. Commissioner Hogan has said there will be a fall of 4% on average in nominal terms in direct payments in the next legislative period, prior to the use of any flexibility by Member States to move funds between the Pillars. To keep the calculations simple, we assume an average direct payment per hectare of €250 in the coming period.

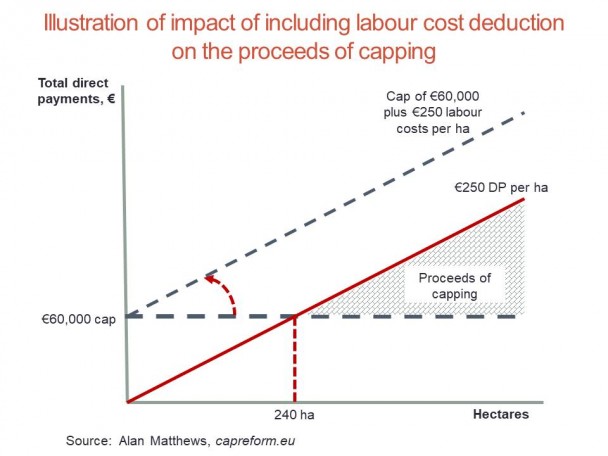

Capping direct payments at €60,000 should mean that the cap becomes binding at a farm size of 240 ha. To demonstrate the way in which first subtracting salaries from direct payments before applying the cap makes the cap meaningless, consider the following graph.

The red line shows that the total direct payments received by a holding increases with the area of the holding. At a holding size of 240 hectares, a cap of €60,000 would become binding. However, with the deduction of labour costs prior to implementing the cap, then the capping threshold is rotated upwards.

In the chart, I have shown an example where the average labour costs per hectare which can be deducted amount to €250/ha (for example, this could arise if the average gross wage per labour unit is €30,000 and the average labour intensity is 1 labour unit for every 120 hectares). I have deliberately chosen this amount as an example because, with this level of labour cost deduction, then net direct payments are always zero!. The capping threshold never intersects with the red line showing the total amount of direct payments received by the holding.

Capping in this example is rendered meaningless by the labour cost deduction.

If the labour cost deduction is less than the average direct payment per hectare, then the capping threshold line is not rotated quite as much, and it is possible it could intersect the red direct payments line at some high amount. If it is greater than the average direct payment per hectare, then the conclusion that capping is meaningless is strengthened even more.

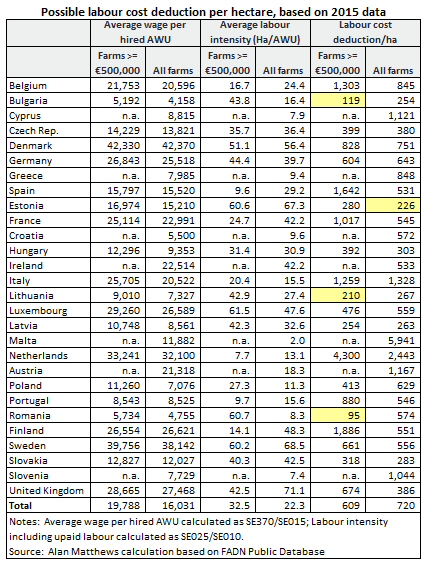

The question then becomes how realistic is the situation shown in the diagram likely to be? To evaluate this, I use FADN data for each country for 2015 (the latest year) showing (a) the average labour cost per hired labour unit; (b) the average labour intensity, measured in hectares per total labour unit, for both all farms and for the largest farm size group (measured in terms of economic size, as FADN does not classify farms by area farmed in the public database); and (c) the derived average labour cost deduction that would be expected in each country under both of these alternatives, assuming the same wage for unpaid labour as for paid labour. The data are shown in the next table.

(click on table for a clearer image)

In general, for most countries the average labour cost deduction is much greater than €250 per hectare, meaning that the net direct payments to which the cap applies will usually be zero. There are only four exceptions in the table. In the case of Bulgaria, Romania and Lithuania, the labour cost deduction on the very largest farms might be only €95-€119 per hectare. In Estonia, the labour cost deduction exceeds €250/ha on the very largest farms, but is somewhat less for all farms.

Note that on the large holdings in Bulgaria, Romania and Lithuania, the FADN data report the labour input used for agricultural production. In a lot of cases, these large holdings will have ancillary enterprises (such as feed milling, packing or transport operations) which may employ additional labour. Although the deduction is for “salaries linked to an agricultural activity actually paid and declared by the farmer”, there is a lot of elasticity in defining which salaries can be assigned to an agricultural activity. My suspicion is that the FADN figures may underestimate the scope for deducting labour costs on the larger holdings in these countries.

My general conclusion is that the graphic is a realistic depiction of the impact of allowing labour cost deductions prior to implementing capping. With the possible exception of some of the very largest holdings in Bulgaria, Romania and Lithuania, the labour cost deduction makes capping meaningless because the net direct payments figure to which capping applies will usually be zero.

The previous analysis has been based on average figures. It is always possible that there will be a handful of farms in the EU that both have large land area but very small labour input, or that have much higher receipts of direct payments per hectare than the value assumed here, and thus the cap will be effective. But these cases will be exceptions and will not alter the general conclusion.

Capping in the 2015-2020 period

This conclusion is supported by the evidence of the (lack of) impact of capping in the current CAP legislative period, even taking into account its much more limited implementation. Recall that only a minimum 5% degressivity is obligatory on payments above €150,000 and that only the basic payment/SAPS payment is taken into account. Even that can be avoided if Member States implement the redistributive pament. On this basis, six Member States do not apply the reduction of payments’ mechanism (BE (Wallonia only), DE, FR, HR, LT and RO). (All data in this section are from the Commission Report on the implementation of direct payments in claim year 2015).

Just 9 Member States capped the amounts of basic payments in 2015 (BE-Flanders, BG, IE, EL, IT, HU, AT, PL, UK (except UK-England)) at maximum amounts ranging from €150,000 (BE-Flanders, IE, EL, AT, PL, UK-Northern Ireland) to €600,000 (UK-Scotland). In other words, 15 Member States (CZ, DK, EE, ES, CY, LV, LU,MT, NL, PT, SI SK, FI, SE, UK-England) opted to apply only the minimum reduction of 5% on amounts of basic payments above €150,000.

Of the 24 Member States implementing degressivity/capping, only 9 Member States made use of the possibility to subtract the salaries actually paid by farmers before applying the reduction of payments’ mechanism: BG, EE, EL, ES, IT, LV, LU, AT and SI. This is interesting given that the leaked draft legislative proposal suggests the Commission wants to make this mandatory in the next legislative period.

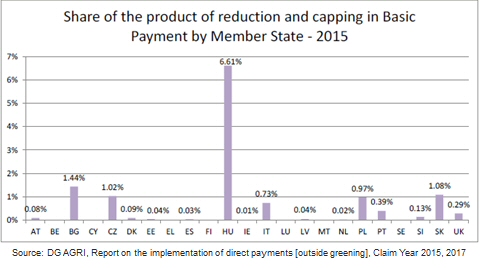

The Member States notified the Commission that the estimated product of the reduction of payments’ mechanism for the 5 years 2015-2019 wil amount to €553 mllion (around €111 million annually). In fact, the amount raised by degressivity and capping was just €98 million in 2015, which represents 0.44% of the basic payment expenditures. The following graph shows the amounts raised in individual Member States.

Only in Hungary has degressivity and capping operated in the current legislative period to yield more than a totally insignificant amount. It is not a coincidence that Hungary did not opt to deduct labour costs from direct payment receipts before applying capping. If capping is to make a difference in the coming period, then the option to deduct labour costs must be removed.

Why deduct salaries?

Why would one want to deduct labour costs before applying the cap (apart from deliberately creating a loophole to make it ineffective)? The principal argument is that larger farms may have a considerable hired labour force. If the CAP has an objective to stimulate rural employment, the argument goes, then it is only reasonable that this employment potential should be recognised in the way the cap is administered.

The CAP Communication proposed to explore a compulsory capping of direct payments to target them more effectively “taking into account labour to avoid negative effects on jobs“. The Commission Staff Working Paper setting out the impact assessment of capping and degressivity prior to the last CAP reform noted: “Introducing a fixed ceiling on payments established at EU level can affect the capacity of large farms to employ and invest. Impacts on employment levels in large farm cooperatives, often located in the EU12, could be substantial”.

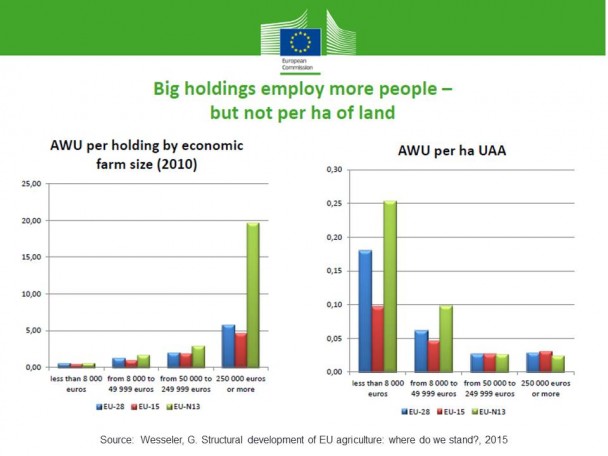

The problem with this argument is that it runs counter to the expressed objective of capping (and the redistribution of direct payments generally) which is to focus support on small and medium-sized farms, in part because of their higher employment potential. In other words, the labour intensity of farms smaller than 240 hectares and receiving less than €60,000 in direct payments is often at least equal to or even greater than the labour intensity of these very large holdings. There is thus no argument based on employment which justifies exempting these very large holdings from a cap on payments.

As noted earlier, the FADN public database does not allow farms to be ranked by area alone to allow this hypothesis to be demonstrated. In any case, it would be important to control for differences in natural conditions (large farms may be located disproporationately in mountainous and other less favoured areas where employment potential is naturally limited).

Looking at the labour intensity per hectare on farms of different economic size is not really a satisfactory alternative. Some farms will be included in the higher economic size categories precisely because they make intensive use of their land area and employ a lot of labour, so there is an element of circularity in using these data to illustrate this point.

For what it is worth, the very smallest economic size groups show the highest labour intensity, but this may reflect underemployment as much as more intensive use of land. For the economic size groups with standard gross margin of more than €25,000, the heterogeneity within countries in the trends in labour use per hectare by economic size is much greater than the differences across size groups at the EU level. As the following chart shows, there is no clear evidence that very large holdings have a higher labour intensity than medium-sized ones.

It is sometimes argued that capping should not be pursued because it will lead to the artificial division of holdings into smaller units to circumvent limits. Indeed, this can be difficult to prevent, as the Commission impact assessment for the last CAP reform noted. However, in the context of this blog post which takes as given the Commission objective to target support on small and medium-sized farms, this surely is a development to be welcomed rather than an argument against the proposal.

A subsidiary argument for allowing the deduction of labour costs is a political economy one, that this is a way of avoiding to penalise farm structures in a handful of newer Member States where large farms emerged from the previous collective farms.

The argument was explored in the Commission impact assessment of the last CAP reform, which observed that a payment cap set at Member States level could better reflect the structure of farms in a given Member State (for instance by taking a multiple of the average amount of direct payments per beneficiary).

However, if the objective is to focus support on small and medium-sized farms, then the fact that average direct payments per farm are increased in some countries with a substantial number of very large holdings is not a relevant issue. Member States could be allowed to use their own national funds in the form of State aid to provide additional decoupled support to these holdings if they felt this was warranted. But there is no argument for using EU budget resources to support these very large holdings when this is not an objective of EU policy.

It could be more relevant to relate the cap or ceiling to average earnings within each Member State. This would imply an even lower limit on payments in the newer Member States where average salaries have not yet reached the average levels in the older Member States.

Finally, allowing the deduction of salaries from direct payments before implementing the gap is likely to discourage labour efficiency in the case of those relatively few farms where the cap is binding. On these farms, there will be an incentive to take on additional labour even if it makes a limited contribution to output, because the effective cost of this labour will be reduced by the additional direct payment that it attracts.

Some may argue that this type of ‘job creation’ is a positive outcome of the way the cap is designed and should be welcomed. However, encouraging the recruitment or retention of low-productivity labour in agriculture and discouraging labour efficiency in this way is not in line with the Communication”s objective to foster a smart and resilient agricultural sector basd on improving the sector’s overall competitiveness and development potential.

Previous experience with capping and modulation

It is also relevant to point out that the deduction of labour costs before the implementation of degressivity and capping was only introduced in the last CAP reform, it did not previously exist in EU policy.

Degressivity (then called ‘modulation’) of larger payments was first introduced in the Fischler Mid-Term Review in 2003. This mandated that direct payments for bigger farms would be reduced by 3% in 2005, 4% in 2006 and 5% from 2007 onwards. Direct payments up to an amount of €5,000 per farm were not affected by this modulation. The purpose here was to raise funds to transfer to Pillar 2 rural development programmes, rather than to cap large direct payments as an end in itself. However, no deduction was seen as needed for labour costs.

The Commission’s original health Check proposal in May 2008 called for a basic modulation rate of 13% by 2013, rising to 22% on payments above €300,000. The actual agreement fell short of this. The rate of modulation was raised by an additional 5% by 2013, somewhat less than the Commission’s original aim of 8%. Again, no need was seen to introduce a deduction for labour costs.

The redistributive payment in the current CAP is funded by top-slicing a proportion of each country’s national ceiling for direct payments, which is then recycled back to small and medium-sized farms. The largest farms are relatively more affected by this measure, but again there is no reference to allowing a deduction for labour costs before the top-slicing is made.

So there is plenty of precedent to suggest that the Commission has been prepared to limit payments to larger farms without necessarily taking into account the deduction of labour costs. These precedents should be used to guide the drafting of the legislative proposals for the coming legislative period.

Conclusions

It is a different argument whether focusing support on small and medium-sized farms is an appropriate focus for agricultural policy in general, and direct payments in particular. I do not address this argument in this post (although I have made clear my scepticism in earlier comments on the Falkenberg paper which advocated this approach).

My view is that there is no particular merit in focusing support on small farms just because they are small. The folly of doing this is only exceeded by the greater folly of focusing support on large farms simply because they large, which is what happens at the moment when payments are linked to area. Payments should be linked to helping farmers to transition to more sustainable modes of production and to the production of public goods, regardless of the size of farm.

Thus I support capping only as a second-best approach in the context where substantial sums of the EU budget continue to be transferred to farmers in the form of area-based payments. The point of this blog post is to suggest that President Juncker and Commissioner Hogan are being downright mischevious in talking up the capping of payments at €60,000 per farm as a way to target support to small and medium-sized farms in the legislative proposals expected at the end of this month.

They must be well aware that the small print of the Commission proposal (allowing the deduction of labour costs including unpaid labour from the amount of direct payments before capping is implemented) means that the proposal will have absolutely no impact in the great majority of, if not all, Member States. In the great majority of cases, the net payments to which the cap will be applied will be zero.

If capping is to be effective, this loophole must be removed, preferably before the publication of the Commission legislative proposals.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Update 12 May 2018. The paragraphs on labour efficiency were added in response to a comment on Twitter on this issue.