The European Court of Auditors has released an Opinion on the draft CAP and CMO Regulations proposed by the Commission. It is a welcome analysis as it moves the discussion on the CAP in the next programming period 2028-2034 beyond the budget and governance issues that have dominated the debate to date, and provides an analytical examination of the changes proposed by the Commission for the CAP interventions themselves. There are many useful insights in the Opinion.

The one interpretation that I found puzzling was the ECA’s discussion of crisis payments for farmers (Article 38 of the Fund proposal). Box 5 in the Opinion appears to suggest that, in the event of natural disasters, access to exceptional measures funded by the EU Facility would only take effect after crisis payments to farmers had been established. My reading of Article 34(9) suggests that it excludes financing crisis payments to farmers in the event of natural disasters by the EU Facility, although why that should be the case is not explained or justified, but it does not require such payments before Member States can seek additional aid from this Facility. Additional insight on how to interpret this paragraph would be welcome from readers.

In this post, I want to focus on one of the key messages in the Opinion:

The greater flexibility granted to member states, while allowing for a more tailored approach, should not put at risk the ‘common’ elements of the CAP, as that could lead to an uneven playing field for farmers and negatively affect fair competition and the functioning of the internal market. To mitigate this risk the Commission will need to play its strengthened steering role effectively.

This fear that the Commission proposal removes the ‘C’ from the CAP is one of the most frequent criticisms made of the proposal. The proposal is seen as leading to the renationalisation of the CAP and to risk disrupting the level playing field that is the bedrock on which the single market depends. COPA-COGECA’s petition calling for a dedicated and increased budget for the CAP has as its second point “Preserve the “C” from CAP: Reject the renationalisation of agricultural policy ! The “C” of the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) must be preserved! Further renationalisation, would fragment the single market, deepen inequalities between Member States, and destabilise rural communities and farmers’ incomes.”

I agree that this is a risk, but it needs to be deconstructed and examined and not simply asserted. We need to keep several issues in mind.

The CAP and a level playing field

The Commission in its Vision for Agriculture and Food, building on the experience of the current CAP Strategic Plans, noted that the current complexity of the CAP called for a more streamlined approach. Its solution was to propose that “The future CAP for post-2027 will rely on basic policy objectives and targeted policy requirements, while giving Member States further responsibility and accountability on how they meet these objectives”.

There is broad agreement that the agricultural challenges that Member States face are not the same, and that flexibility is needed under the CAP to allow these differences to be addressed. For some Member States, the key priority remains modernisation of agricultural structures and raising productivity, for others it is generational renewal, for others it is a desire to support traditional farming structures in vulnerable rural areas, while for yet others it may be addressing the environmental footprint of intensive agricultural systems. For this reason, Member States themselves demand greater flexibility.

Nor has the CAP ever been implemented uniformly across Member States. The level of Pillar 1 direct payments per hectare in Member States partly reflects historic differences in the intensity of market price support, but also the negotiating outcomes of the accession processes in 2004/2007 and later. Despite successive efforts at external convergence over the last two CAP reforms, differences in the level of payments per hectare continue in the current CAP.

The level of Pillar 2 payments per hectare are even more skewed, in part deliberately as rural development funding, seen also as an element of structural funding, plays a cohesion role as well as being part of CAP.

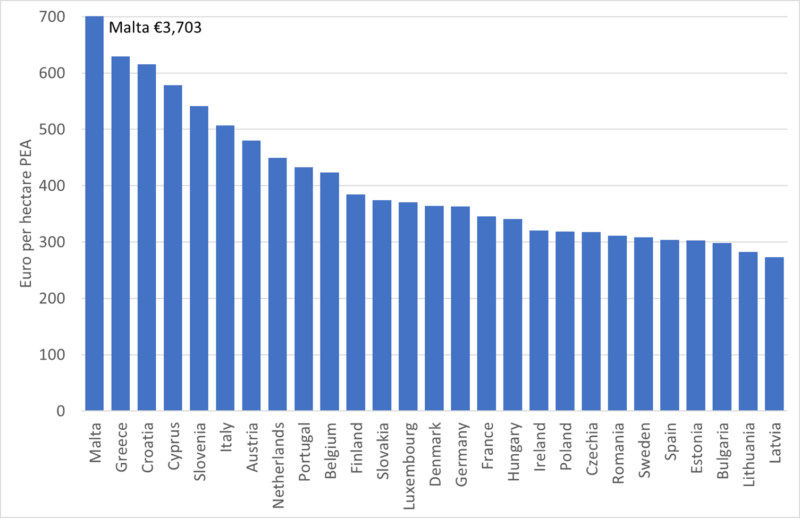

Total CAP pre-allocated receipts in 2027 per hectare of Potentially Eligible Area are shown in Figure 1. Even leaving aside Malta (where each hectare of its 6,644 ha PEA will receive an average of €3,703 in CAP receipts in 2027), there is significant variation, ranging from Greece with receipts of €630/ha PEA to Latvia with receipts of €273/ha PEA. This variation could also be demonstrated by expressing CAP receipts per ha Utilised Agricultural Area. This figure is close to the Potentially Eligible Area for direct payments in many Member States but significantly larger in some Member States such as Spain, France, Italy, Bulgaria and Romania which would lower the figures shown for these countries in this chart. Nor are hectares the only basis for comparison. One could also express the differences per person or per Annual Work Unit of the farm labour force, per holding or as a share of value added or farm income.

Sources: Commission, Budget pre-allocations web page; Commission, Summary report on the implementation of direct payments (exc. Greening) Claim Year 2022, Table 1.1.

Differences in the way the CAP is perceived by farmers in different Member States are not confined just to the monetary amounts received. Member States have considerable flexibility to define the standards for conditionality that farmers must meet for eligibility for payments. In some Member States, a significant share of direct payments is paid as coupled payments which clearly distort competition in the single market, in other Member States almost none. Some Member States have designed their eco-schemes as almost pure income transfers, in that most farmers were able to qualify without any change in their farm practices. Other Member States set a higher bar, requiring farmers to adopt specific (and costly) measures to be eligible for payment. And so on. The current CAP is far from the ideal level playing field that is sometimes imagined.

How the Commission proposal might exacerbate differences in support

Still, there are reasons why the Commission proposal could exacerbate these differences, as the Court of Auditors and others have pointed out. The minimum ring-fenced CAP amounts for income support are based on the Member State shares in CAP receipts in 2027 and thus will replicate the disparities that are illustrated in Figure 1. However, on top of that, Member States have the option to add to these amounts from the unearmarked portion of their overall allocation under the National and Regional Partnership Fund. It can be expected that Member States will top up their minimum CAP allocations by different proportions, in part because the financial scope to do so is more restricted in some Member States than others (see my calculations here in this blog post), and in part because of differing political priorities in Member States.

Member States will also have greater flexibility in the allocation of the CAP funds that they receive, due to the elimination of specific minimum ring-fencing requirements (for example, for agri-environment-climate actions or for the amount to be allocated to the redistributive payment) or the increase in maximum ceilings. Particularly the increase in the maximum ceiling for coupled payments should be underlined, as this payment is the most distorting of the level playing field in the single market. The increase in this ceiling comes as a result of sustained pressure from many Member States. Indeed, those Member States critical of the Commission proposal for renationalising the CAP are sometimes those who themselves have contributed most to this renationalisation.

There are other areas where the Commission proposal could lead to a less common CAP. The Court of Auditors highlights that the lack of a clear common framework for definitions such as ‘active farmer’ or ‘small farmer’ could create an uneven playing field for farmers. Member States have even greater flexibility to define the protective practices under farm stewardship as compared to the GAEC standards under conditionality. Member States would also have the possibility but not the obligation to compensate farmers for the cost of implementing these protective practices, and it can be envisaged that some will do so and others not.

These considerations raise several questions. Given that Member States desire flexibility in the implementation of the CAP, and that considerable differences in implementation already exist, how much more damaging would some additional flexibility be in practice? Is flexibility like an elastic band, where you can stretch it so far without creating difficulties, but there comes a point where the elastic just snaps and no longer functions? How close are we to this breaking point at present? Is there an objective way to establish where this breaking point lies? I am not aware of academic research that attempts to throw light on this question.

Another question is whether greater flexibility undermines the ability of the CAP to provide real EU added value. The Court of Auditors in its Opinion notes that EU value added depends on the CAP being used to fund interventions that address EU-wide challenges which could not be addressed as effectively by national funding alone. It provides a list of main challenges as follows:

- a system of fair competition and consistent rules for farmers in an open single market;

- a common framework for agricultural support that does not distort or fragment the internal market, and a strategic use of financial resources focused on ensuring fair income for farmers;

- a strengthened and guaranteed food-security system, even in the event of crises;

- a coordinated protection of the environment, climate and biodiversity, and of know-how in the area of food supplies.

The danger lies in too much flexibility that allows Member States to design their agricultural policies solely on national criteria, so that the CAP becomes purely a financial transfer mechanism between net contributors and net recipients without any real EU value added. It is clear that such an outcome would not be sustainable in the longer term.

The solution in the Commission’s proposal to address this second question is the Commission steering mechanism (Article 22(2)(b) of the Fund proposal and Article 2 of the CAP proposal). I do not discuss this mechanism in this post and whether it is likely to be effective. The AGRIFISH Council will devote part of its next meeting on 23 February 2026 to this topic, on the basis of a background note prepared by the Cyprus Presidency. This policy debate will give greater insight into how Member States would like to see this mechanism working.

Variability in the new DABIS payment

Interestingly, there is one area where the Commission claims that it is limiting rather than increasing flexibility although this is not evident at first sight. This concerns the minimum and maximum limits proposed for the new degressive area-based income support (DABIS) payment per hectare. The planned average aid per hectare for DABIS should be not less than €130 and not more than €240 for each Member State (Article 35(3) of the Fund Regulation). This wide range suggests the potential for even more divergence between Member States than observed under the present CAP.

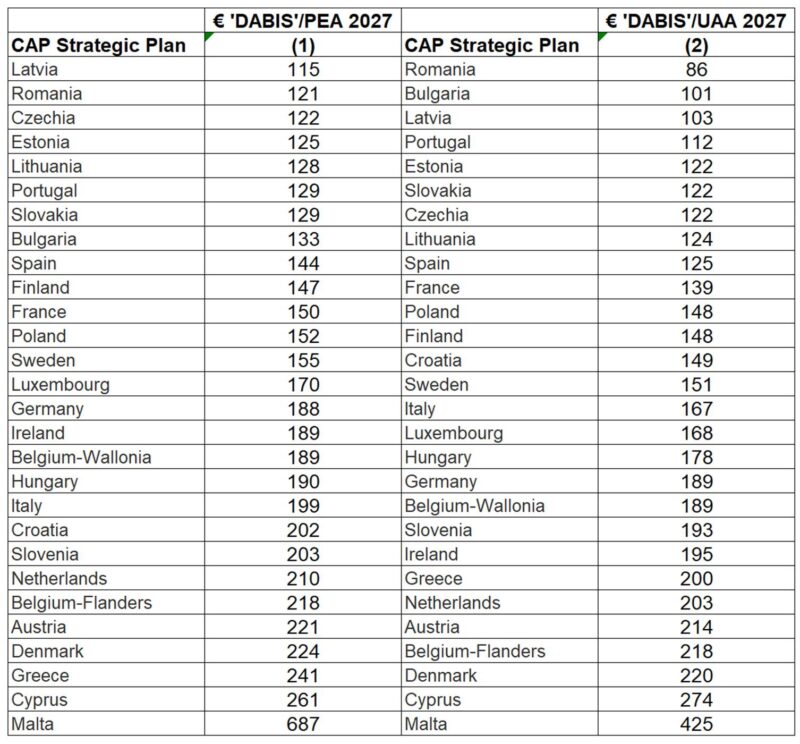

However, the Commission argues that this range is actually narrower than the range in payments in place under the current CAP. Indeed, this seems to be the case (Table 1). In the following, we consider only the average ‘DABIS’ payment in Member States, ignoring the requirement in Article 6(2) of the draft CAP Regulation that Member States are required to differentiate this payment by groups of farmers or geographical areas, on the basis of objective and non-discriminatory criteria.

Notes: ‘DABIS’ payment in 2027 is defined as the sum of BISS, CRISS and CIS-YF payments. For Belgium, where there is little overall difference in PEA and UAA hectares, the PEA hectares for the two regions for which data are not available are assumed to be the UAA hectares for which there are data. I have chosen to use data for FY2027 which refers to claim year 2026 for direct payments as the source shows significant changes in payments in FY 2028 for a few countries as well as an overall increase in payments which I find hard to explain as it lies outside the 2021-2027 MFF programming period.

Sources: Data for the BISS, CRISS and CIS-YF payments are obtained from the DG AGRI workbook ‘Planned financial allocations by type of intervention under the 2023-2027 CAP’. PEA data for 2022 from Commission, Summary report on the implementation of direct payments (exc. Greening) Claim Year 2022, Table 1.1. UAA data for 2027 are from the JRC CSP Master file August 2023.

To construct Table 1, we first assume that the DABIS payment will replace three payments in the current CAP – the BISS, CRISS, and CIS-YF. I have summed the amounts that each Member State allocates to these three payments in 2027. In column (1), I have expressed these amounts per hectare of Potentially Eligible Area. I have used 2022 data for PEA as in Figure 1 because I have not found reported data for the new CAP programming period 2023-2027. There could be minor changes in the PEA areas with the introduction of the new CAP, so the figures in column (1) should be seen as best approximations of the 2027 outcome.

The choice of the PEA as the denominator could be contentious as this is left unspecified in the draft Fund Regulation. Article 35(3) simply specifies a minimum and maximum DABIS amount “per hectare”. How to define this hectare is not specified. In the definitions Article in the draft Fund Regulation, there is guidance for how Member States should define an “eligible hectare” (Article 4(22)c). If it were intended that the DABIS payment limits should be interpreted as per eligible hectare, then this should be stated for legal clarity.

As it is, there is uncertainty how the Commission intends these limits to be defined. In column (1), I have assumed that the Commission has intended “eligible hectare” as the denominator. I redo the calculation in column (2) using UAA hectares as the denominator. The UAA figures are taken from the JRC CAP Strategic Plans Master file prepared in August 2023 and refer to the year 2027. There are differences in the ranking of Member States between the two columns where there are significant differences between PEA and UAA areas in these countries.

Based on PEA areas in column (1), the range for the ‘DABIS payment’ (that is, the sum of BISS, CRISS and CIS-YF) in 2027 will lie between €115 for Latvia to €261 for Cyprus (for this purpose I leave Malta aside because it is very much an outlier, as indicated in Figure 1). On this rather crude comparison, we can say that the Commission proposal to limit the range to €130 to €240 per hectare represents a narrowing.

If we assume that the proposed range for the DABIS payment were based on UAA areas, then the case for narrowing is even stronger. Here, the projected range in 2027 will be from €86 in Romania to €274 in Cyprus (again leaving Malta to one side) (column (2)).

Looking only at the proposed ranges overlooks a potentially significant outcome of the Commission proposal. The possibility for Member States to choose an average DABIS payment anywhere between €130 and €240 per hectare opens the possibility for those Member States that currently (or, more accurately, are projected to receive in 2027) have low ‘DABIS’ payments to significantly increase these payments. Poland, for example, which currently has a ‘DABIS’ payment of €156/PEA hectare (€148/UAA hectare) could increase this to €240 per hectare. Similarly, Spain with a 2027 ‘DABIS’ payment of €144/PEA hectare (€125 per UAA hectare) could do likewise. On the other hand, farmers in Denmark who currently receive a ‘DABIS’ payment of €224/PEA hectare (€220/UAA hectare) could in principle see these payments reduced to €130 per hectare under the Commission proposal. This speculation is not intended to suggest that these countries will make these changes, but it does indicate the scope for a very different landscape of direct income support for farmers under the draft Regulations.

Conclusions

There is a widespread concern that the increased flexibility for Member States in the Commission’s proposal for the CAP 2028-2034 will lead to greater differences in support to farmers and further undermine the idea of a level playing field for farmers within the single market. This concern should be taken seriously.

However, in this post I suggest that the debate needs to be more nuanced. I point out that there is widespread recognition that the CAP cannot have a ‘one size fits all’ architecture and there is considerable pressure from Member States for greater flexibility. The debate should also consider the considerable lack of uniformity that currently exists in the way the CAP is implemented in different countries. Further, I point out that, with respect to the level of the DABIS payment which is where most of the concern is focused, there is evidence that the Commission proposal reduces the extent of differentiation compared to the current CAP, something that has not been highlighted previously in the debate. There is much less concern and angst among farmers about differences in the budgets available for agri-environment-climate action between Member States (at least under present rules where payments are limited in principle to costs incurred and income foregone – this could change if these payments shift to become more of an income top-up).

Various measures have been proposed to limit the extent of flexibility with the objective of minimising potential distortions to the level playing field. The most popular call is to reintroduce minimum ring-fencing requirements (for young farmers, for agri-environment-climate actions). The limitation with this approach is that quantitative budgetary allocations say little about the level of ambition of these payments, as we see currently with eco-schemes.

But it is clear that drastically reducing the maximum ceiling for coupled supports (I would make an exception for protein crops) should be an obvious priority, as these are the most distorting payments (by contrast, differences in decoupled DABIS payments largely impact the structure of agriculture by slowing the exit of smaller farms rather than increasing the average income of those farmers who remain in farming in the longer term). But those who criticise the Commission proposal most loudly for risking the renationalisation of the CAP are also those who call for the maintenance and even increase in coupled payments (see the European Parliament resolution of 10 September 2025 on the future of agriculture and the post-2027 common agricultural policy (2025/2052(INI)), paragraph 19).

The bigger question, I suggest, is how to ensure, in spite of giving Member States needed flexibility in the implementation of the CAP, that the CAP can continue to deliver European value added. In the absence of demonstrable European value added, the CAP becomes just a financial redistribution mechanism without long-term prospects. There is a huge weight of expectation on the Commission steering mechanism to fulfil this role, which I fear it will be unable to bear. This is an area where academic research could play a really important and significant role.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit: European Parliament, used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

Update 26 Feb 2026. The paragraph referring to the ECA Opinion’s discussion of crisis payments to farmers has been amended, and a typo referring to Article 34(9) was corrected.