I am not an expert in nutrition and, if I am honest, I have been sceptical of the significance of occasional health-related claims such as the claimed link between red meat and cancer. But that there is a link between diets and ill-health is indisputable. What is less clear is the nature of these links, which has been brought into sharp focus by the publication of the latest U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2025-2030 by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins two days ago on 7 January 2026.

In 2021, the OECD published a report prepared by Koen Deconinck Making Better Policies for Food Systems which argued that achieving better food policies for food systems requires overcoming frictions related to facts, interests and values. The latest U.S. Dietary Guidelines provide a relevant case study of the way differences in the interpretation of facts can influence policy recommendations. Of course, the way facts are interpreted are influenced by interests and values.

This is particularly relevant in the present case given Secretary Kennedy’s prior public record on diet-related ill health, as articulated through his Make America Healthy Again agenda. This agenda frames rising chronic disease as the outcome of structural failures in the food system, emphasising the role of ultra-processed foods, excessive sugar consumption, and industrial food formulations, while expressing scepticism about long-standing low-fat dietary paradigms.

It promotes a return to whole foods, higher protein intakes, and reduced reliance on refined carbohydrates, and places strong emphasis on prevention, metabolic health, and reduced dependence on pharmaceutical treatment (Reuters, 2026). While several elements of this framing resonate with mainstream nutrition debates, the prioritisation of animal-source foods and the relative de-emphasis of established concerns around saturated fat have been viewed by parts of the nutrition community as reflecting a selective emphasis within the existing evidence base.

Diets and health

Many European Union populations face significant diet-related health challenges (European Commission 2024; World Health Organization 2022). According to Eurostat, more than half of adults in the EU live with excess weight, with obesity rates increasing steadily across most Member States over the past decade. The World Health Organization estimates that overweight and obesity are major risk factors for non-communicable diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, and several cancers, and that diet-related risk factors account for a substantial share of avoidable morbidity and premature mortality in Europe. These outcomes are unequally distributed, with higher prevalence among lower-income and lower-education groups, reinforcing concerns about social gradients in health.

Diet and food consumption patterns are central to debates about these trends. Public authorities at EU and national level increasingly point to high intakes of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, excess consumption of added sugars, saturated fats and salt, and insufficient intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains and fibre as key drivers of poor health outcomes. At the same time, there is disagreement about the relative importance of specific dietary components and about the most effective policy responses.

Three areas of controversy are particularly salient. First, ultra-processed foods have become a focal point of debate. Using the NOVA classification, these foods are defined as industrial formulations containing multiple ingredients and additives and designed for convenience and palatability. Observational studies associate high consumption of ultra-processed foods with obesity and other non-communicable diseases, but critics question whether these associations reflect causal effects or broader lifestyle and socioeconomic confounding (Monteiro et al. 2019: UK Standing Advisory Committee on Nutrition, 2023, 2025).

Second, saturated fats remain contested. Long-standing dietary advice has emphasised limiting saturated fat intake due to its association with raised LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular risk, yet some recent analyses argue that food matrices and dietary patterns matter more than individual nutrients (Mozzafarian et al., 2010; Astrup et al., 2020).

Third, added sugars, particularly in sugar-sweetened beverages, are widely implicated in obesity and metabolic disease, although debate persists over appropriate regulatory tools and thresholds (World Health Organization, 2015).

Why nutritional advice is particularly prone to revision

Nutritional science is especially vulnerable to shifts in interpretation because of the nature of its evidence base (Ioannidis, 2013). Long-term randomised controlled trials of whole diets are difficult to conduct due to ethical, practical, and financial constraints. Diets cannot be blinded, adherence is hard to enforce over extended periods, and health outcomes of interest often take years or decades to manifest. As a result, much of nutritional evidence relies on observational and epidemiological studies, which are sensitive to measurement error, confounding, and model specification.

Dietary intake data are commonly based on self-reported food frequency questionnaires or recalls, which are known to be imperfect. Small changes in analytic assumptions, population selection, or statistical adjustment can materially affect estimated associations. As methods evolve and new cohort data become available, earlier conclusions may be revised. This does not imply that nutritional science is arbitrary, but rather that uncertainty is higher than in fields where controlled experimentation is more feasible. These features make nutritional advice particularly exposed to reinterpretation and policy change.

The 2025–2030 U.S. Dietary Guidelines

The new U.S. dietary guidelines represent a marked shift in emphasis relative to earlier editions. For one thing, they are much shorter (a total of 9 pages compared to 164 pages for the 2020-2025 version). They place greater weight on whole, minimally processed foods and explicitly discourage consumption of ultra-processed foods. Protein is given a central role, with recommended intakes increased from the long-standing benchmark of 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day to a range of approximately 1.2–1.6 grams per kilogram per day for adults, with animal-source foods such as meat, poultry, eggs, seafood, and full-fat dairy explicitly presented as acceptable components of healthy dietary patterns alongside plant-based protein sources.

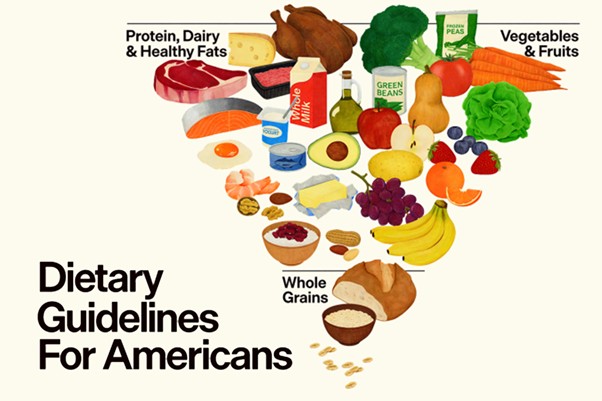

Added sugars are framed as undesirable at any level, with guidance indicating that intakes should be kept very low, in practice not exceeding roughly 10 grams per meal. Saturated fat is formally retained under a quantitative cap of less than 10% of total daily energy intake, but this constraint is less prominently emphasised than in earlier editions. Guidance on alcohol no longer specifies numerical limits to one or two drinks per day; instead, the text states that Americans should consume alcohol in moderation and that drinking less is better for health, with abstention recommended for some population groups. These recommendations are accompanied by revised visual guidance, elevating protein and fats from whole foods relative to refined carbohydrates and grains.

Compared with previous editions, which stressed balance across food groups, favoured low-fat dairy, and consistently highlighted saturated fat reduction, the new guidelines adopt a more permissive stance toward animal products and dietary fats. While some numerical limits, such as the cap on saturated fat as a share of total energy intake, formally remain, the overall framing departs from the MyPlate paradigm that has structured US dietary advice for more than a decade.

Scientific disagreement and the role of interpretation

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2025–2030 illustrate how apparent disagreements over facts emerge through processes of interpretation and prioritisation within particular political and institutional contexts. Reactions within the scientific and public health communities to the publication of the Guidelines highlight how the same body of evidence can be read in different ways. Supporters argue that the stronger focus on protein and whole foods reflects emerging evidence on diet quality, metabolic health, and the limited benefits of low-fat formulations. Critics counter that the guidance risks downplaying robust evidence linking high intakes of saturated fat and red and processed meat to cardiovascular disease, and that it may confuse the public by appearing to reverse long-standing advice.

But there are concerns whether these differences in interpretation do not also reflect industry influence in the development of the guidelines (Center for Science in the Public Interest 2026). Under the standard U.S. process for updating the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, a Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee is periodically appointed under the Federal Advisory Committee Act to conduct an independent review of the scientific evidence on diet and health. The Committee’s Scientific Report is intended to provide the primary evidence base on which the Departments of Health and Human Services and Agriculture then develop successive editions of the Dietary Guidelines. In the 2025–2030 cycle, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee was established under the Biden Administration. In December 2024, the Committee published its Scientific Report setting out its assessment of the evidence base and its recommendations. However, the final 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines diverge in important respects from that report.

Instead, Secretary Kennedy dismissed the Advisory Committee’s Scientific Report on the grounds “that it had framed its analysis through a health equity lens”. Instead, the Secretary selected a new group of nutrition experts and panels to produce an alternative Scientific Foundation for the Dietary Guidelines. Media investigations indicate that several members of these review groups disclosed financial ties to meat, dairy, infant formula, or supplement industries. Such institutional arrangements can shape problem framing, evidence weighting, and the translation of scientific findings into policy advice, even in the absence of explicit interference. More broadly, this episode can be interpreted through the lens of the commercial determinants of health (World Health Organization 2023), which emphasise how corporate strategies such as research funding, lobbying, and participation in advisory processes can influence nutrition science and policy .

The apparent tension between Secretary Kennedy’s long-standing criticism of the food industry and the appointment of nutrition experts with close ties to specific producer sectors has been explained in several ways. One is a distinction, implicit in the Make America Healthy Again agenda, between highly processed food manufacturers, which are portrayed as central contributors to poor health, and producers of what are framed as “real” or traditional foods, such as meat and dairy, whose interests are treated as less problematic. A second explanation emphasises expertise rather than neutrality: given the pervasiveness of industry funding in nutrition research, it is argued that strict exclusion of experts with industry ties would significantly narrow the pool of qualified advisors, with disclosure seen as a sufficient safeguard. A third interpretation points to political economy considerations, noting that livestock and dairy sectors are economically and electorally significant in the MAGA base and that accommodating their interests can help stabilise support for dietary guidance that would otherwise face resistance.

Beyond disagreement over the interpretation of evidence within the accepted scientific domain, political choices also shape the scope of admissible evidence itself. A further illustration of how interests and values shape which facts enter policy debates concerns the treatment of environmental sustainability. In several countries, including Canada and a number of EU Member States, recent dietary guidelines explicitly integrate evidence on environmental impacts, such as greenhouse gas emissions and resource use, alongside nutritional considerations. In the United States, the scope of relevant evidence is itself politically circumscribed.

For the 2025–2030 cycle, the terms of reference given to the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee explicitly confined its remit to diet–health relationships, excluding consideration of environmental sustainability. This exclusion reflects a longer-standing political process, reinforced by congressional direction since the mid-2010s, that has sought to keep environmental considerations outside the Dietary Guidelines framework, particularly following industry and congressional opposition to earlier attempts to link reduced red meat consumption to environmental sustainability outcomes (the evolution of the Guidelines and the controversy around the 2015-2020 Guidelines are described in U.S. Congressional Research Service, 2023). As a result, neither the Committee’s Scientific Report nor the final Dietary Guidelines engage substantively with environmental evidence, despite its growing prominence internationally.

Conclusion

The debate surrounding the latest U.S. dietary guidelines illustrates how disagreements over facts are frequently politically mediated. They are shaped not only by scientific uncertainty, particularly prevalent in nutrition science, but also by underlying interests and institutional arrangements.

Where evidence is complex, probabilistic, and methodologically constrained, scientific interpretation plays a decisive role. Different judgments about the strength, relevance, and implications of evidence can legitimately lead to different policy recommendations. However, when combined with concerns about commercial influence, these disagreements can undermine trust and intensify politicisation. The deliberate exclusion of environmental sustainability from the evidentiary remit of the Dietary Guidelines process further underscores that political choices about scope and relevance shape not only how facts are interpreted, but which facts are permitted to enter policy deliberation at all.

Nutrition policy thus exemplifies how facts in food policy do not speak for themselves: they are interpreted, weighted, and sometimes excluded through political and institutional processes that reflect underlying interests and values, rather than scientific uncertainty alone.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Acknowledgement: I am not a nutrition expert. For this post, I have used ChatGPT, a large language model developed by OpenAI, for assistance in structuring the argument, clarifying points of interpretation, and identifying relevant sources. I have critically reviewed the material provided, and I remain responsible for the final text.