The Commission published its Communication The future of food and farming in November 2017 following an extensive public consultation process. Legislative proposals accompanied by an impact assessment are expected at the end of May. At the same time, the UK is preparing for life after Brexit. To this end, the UK Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) published a Command Paper (consultation document) on February 27 seeking views on a future post-Brexit agricultural policy. The paper provides a clear direction of travel for UK, or at least, England’s future agricultural policy, and will result in a White Paper and legislation in the form of an Agricultural Bill later in this parliamentary session. A comparison of the policy proposals in the two documents is thus of some interest.

An important clarification is needed at the outset. Agricultural policy is one of the devolved competences in the UK, meaning that the three devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland each have responsibility for the design of their own agricultural policies (presently, of course, within the parameters of the CAP legislation). Only in England is agricultural policy determined in Westminster. Thus, the ideas in the Command Paper are solely relevant to future agricultural policy in England, as there is no guarantee (and, indeed, it is highly unlikely) that these ideas will be supported by the three devolved administrations.

Overall objectives

The Commission Communication is called The future of food and farming with a focus on modernisation and simplification. The UK Command Paper is entitled Health and harmony: the future for food, farming and the environment in a Green Brexit. The latter’s outline of a plan to change the use of land so as ‘to better promote health and harmony’, as DEFRA Secretary of State Michael Gove puts it in the foreword to the document, certainly seems more poetic and post-materialist than the more prosaic title of the Commission’s work. However, the two documents differ not so much in their stated objectives for farm and food policy, although there is one important difference, but more in the ways they plan to move farming in the direction of those objectives.

The EU Communication sets out the following three objectives for agricultural policy:

• To foster a smart and resilient agricultural sector, including a fair income support to help farmers to make a living; investment to improve farmers’ market reward; and risk management.

• To bolster environmental care and climate actions and to contribute to the environmental and climate objectives of the EU.

• To strengthen the socio-economic fabric of rural areas, by promoting growth and jobs in rural areas and by attracting new farmers.

The UK Command Paper sets out three very similar objectives for agricultural policy as follows:

• Providing support to encourage industry to invest, raise standards and improve self-reliance, including making sure that farmers have access to the tools needed to effectively manage their risk.

• Setting the regulatory baseline to protect high environmental, plant and animal health and animal welfare standards and creating a level playing field for farmers and land managers, while rewarding farmers and land managers to deliver environmental goods that benefit all, including high animal welfare.

• Helping rural communities prosper, including through improving physical and digital connectivity.

Both documents also have a strong simplification focus. In the case of the EU Communication this is to be pursued in part through a new delivery model for the CAP (moving away from a compliance-based to a performance-based model). In the case of the UK Command Paper, it will be pursued through smarter regulation and enforcement. The UK has already set in train a comprehensive review of farm inspection, seeing how inspections can be removed, reduced or improved to lessen the burden on farmers while maintaining and enhancing animal, environmental and plant health standards.

The most important difference in farm policy objectives is that, in the UK Paper, unlike the EU, the level of farm income is not a specific objective. The UK Command Paper mentions income only in the context of income volatility, apart from a reference to exploring ways to support farming in upland areas where farming activity is more restricted. The omission of a specific commitment to support farm income lies behind the biggest difference between the two documents, which is their attitude to direct payments.

Direct payments

For the EU Communication, direct payments partially fill the gap between agricultural income and income in other economic sectors. It also argues that they provide an important income safety net, ensuring there is agricultural activity in all parts of the Union, including in areas with natural constraints. It asserts that the resulting agricultural activity provides various economic, environmental and social associated benefits, including the delivery of public goods. It therefore advocates that direct payments will remain an essential part of the CAP in line with its EU Treaty obligations.

The UK Command Paper takes a very different view of direct payments. It argues that direct payments are poor value for money, untargeted and can undermine farmers’ ability to improve the profitability of their businesses. They have distorted land prices and rents, can stifle innovation and impede increases in productivity. It therefore proposes to move away from direct payments in England, eventually phasing them out altogether. Instead, they would be replaced with a system of public money for public goods, principally environmental enhancement.

The Command Paper recognises that direct payments cannot be switched off overnight and that a transition to a replacement system will be needed. It proposes to pay the 2019 Basic Payment Scheme in England broadly on the same basis as at present. It then proposes an ‘agricultural transition’ period, in which direct payments will be gradually reduced over a number of years, starting with those receiving the highest payments, in order to free up money to help the industry to prepare for the future and to pilot new environmental land management schemes.

The colour-coded version of the draft Withdrawal Agreement agreed by the two negotiating teams on 19 March specifically provides (Article 130(1)) that the CAP’s direct payments regulation will not apply in the UK in the claim year 2020.

Changes introduced in the Omnibus Agricultural Provisions Regulation anyway give Secretary of State Gove some of the flexibility he needs to start on the rebalancing of support. Under the 2013 CAP reform, Member States had to apply the principle of degressivity to direct payments over €150,000, reducing these payments by at least 5% but potentially up to a reduction of 100% (which effectively implies capping payments at this level). England chose to remain at the minimum level of 5%, on the basis that it did not want to penalise larger, more competitive, farms.

Under the 2013 Direct Payments Regulation, Member States had a once-off opportunity to make their decision which would apply to the claim years 2015 through 2019. The Omnibus Regulation has introduced an additional flexibility that Member States can now revisit their choices on an annual basis, provided that the review does not lead to a reduction in the amounts available for rural development. This would allow the UK government to announce before 1 August 2018 that it was capping payments above €150,000 in the claim year 2019 with the savings devoted to the proposed new pilot agri-environment schemes as the first step towards the promised rebalancing of support.

Perhaps surprisingly, given the legitimate emphasis in the Command Paper that farmers need as much certainty about future policy as possible, no announcement was made to this effect. As the Command Paper consultation seeks opinions on whether the reduction in payments should be progressively applied to all beneficiaries, or should be solely targeted at those with the largest payments, it may have been felt that making such an announcement would have pre-empted the results of the consultation.

There are a number of issues around the ‘agricultural transition’ period and beyond which merit further discussion.

• There is an implicit assumption that farmers currently relying on direct payments to make up their income will be able to make up for the elimination of direct payments by enrolling in the proposed new environmental land management system. On p. 20, the Command Paper states: “We understand that many farm businesses currently rely on Direct Payments to break even… Farmers may wish to apply for payments under our new environmental land management system and we will seek to involve them in trials of this system during the ‘agricultural transition’.” Many farmers are sceptical that agri-environment schemes can be a genuine source of additional income, as opposed to mainly covering the costs in terms of income foregone of enrolling in such schemes. The Command Paper commits to achieve better environmental outcomes and improve value for money, suggesting innovative mechanisms such as reverse auctions, tendering, conservation covenants and actions which encourage private investment in natural capital. At least some of these mechanisms are likely to erode the rents that farmers might otherwise expect to receive from environmental payments.

• It is recognised that farmers need assistance to help them prepare for a future without direct payments support. The Command Paper provides that the two processes will proceed in parallel, in that reductions in direct payments provide the funding for the necessary assistance. To the extent that direct payments are currently used to fund living expenses, it will be difficult for farmers to use the payments to invest in and adapt their businesses. If direct payments are terminated over a relatively short time period, farmers may not have time to benefit from any investments or structural changes designed to improve productivity and their competitiveness in a world without such payments. The consultation explicitly asks for views on how long the agricultural transition period should be.

• The Command Paper recognises that farmers in remote areas may need tailored support, but the way in which farming, land management and rural communities in the uplands should be supported to continue delivering environmental, social and cultural benefits is also left as a question in the consultation.

• Finally, the Command Paper floats a version of the idea of a ‘bond scheme’ first put forward by Stefan Tangermann in a 1991 article and elaborated in the 2004 book Bond Scheme for Agricultural Policy Reform edited by Alan Swinbank and Richard Tranter. In a bond scheme, the future time-limited entitlements to direct payments would be capitalised in a bond that would be traded on financial markets. The advantage as seen by proponents is that farmers are no longer tied to their land in order to receive these payments, giving them greater flexibility in how to use the proceeds of the bond. The Command Paper does not go quite that far. It envisages an option whereby payments would continue to be made to existing farmers ‘irrespective of the area farmed’. Farmers could choose to use the payments to invest in or adapt their businesses (though recall the caveat above that at least in some cases farmers currently use these payments for living expenses which it will be difficult to forego) or to exit the sector. Again, views are sought in the consultation on whether this should be an option during the ‘agricultural transition’ period.

Greening architecture

The EU Communication proposes a new approach to achieving the EU’s environmental and climate objectives. The current green architecture of the CAP – cross-compliance, green direct payments and voluntary agri-environment and climate measures – will be replaced by a more integrated, targeted yet flexible approach. The granting of income support to farmers will be conditioned to their undertaking of environmental and climate practices which will become the baseline for more ambitious voluntary practices.

This new conditionality – which will replace cross-compliance and greening – will be designed by Member States as a mixture of mandatory and voluntary measures to meet the agreed environmental and climate objectives defined at EU level. However, exactly how this new conditionality will differ from the combination of cross-compliance and greening measures remains to be spelled out.

The UK Command Paper proposals for new environmental land management schemes could have been designed to fit into the Commission’s proposed new flexibility for Member States. From the end of the ‘agricultural transition’, it promises a new environmental land management system to be the cornerstone of agricultural policy in England. The system will be designed to deliver the government commitment to be the first generation to leave the environment in a better state than it inherited it.

The Command Paper contains a chapter (Chapter 5) defining the public goods that will be supported, and a chapter (Chapter 6) that sets out some ideas on what elements might be included in the new environmental land management system. Like the Commission Communication, however, the proposed new system is only rather vaguely outlined, more a set of principles than a specific roadmap.

One of the issues that both the EU and UK will have to address in designing their new greening architecture is where the dividing line should be drawn between polluting activities and public goods (I discuss this issue at greater length in this paper). The elimination of direct payments also means the disappearance of cross-compliance. The UK government will have to decide which of the measures in cross-compliance will become part of good farming practice which farmers are expected to undertake as part of their ‘licence to farm’, and which will fall into the category of public goods for which farmers can expect to be rewarded.

The Command Paper states that “A strong baseline will maintain and enhance important environmental, animal and plant health and animal welfare standards, backed by an integrated inspection and enforcement regime”, but it gives no indication of the measures that will be included in the baseline.

One exception is the case of high animal welfare which the Command Paper emphasises must be at the heart of a world-leading food industry. Here the Command Paper proposes to leave the legislative baseline as it is, but suggests that pilot schemes that offer targeted payments to farmers who deliver higher welfare outcomes in sectors where animal welfare largely remains at the legislative minimum could be introduced.

This debate over where to draw the baseline will also be a crucial element in the future EU greening architecture which leaves it up to Member States to devise a mixture of mandatory and voluntary measures in Pillar I and Pillar II to meet the environmental and climate objectives defined at EU level.

Conclusions

There are some obvious similarities between the future farm and food policies outlined in the Commission Communication and UK Command Paper, but also some significant differences. The most significant difference is that using public money to directly support farm incomes is no longer an objective of English agricultural policy. Following from this, the Command Paper proposes the phasing out of direct payments and a greater focus on using public money for public goods.

The most important public good identified in the Command Paper is protection and enhancement of the environment, but better animal and plant health, animal welfare, improved public access, rural resilience and productivity are also seen as areas where government could play a role in supporting farmers and land managers in the future. While some principles behind the proposed new environmental land management policy are spelled out, a more detailed roadmap remains to be developed. There is a similar lack of clarity in how the proposed new greening architecture will work in the Commission Communication on the CAP post 2020.

At present, all we can do is to compare two documents. But if the UK does implements its policy vision for England, it will provide a fascinating role model and case study of agricultural policy change. Once the ‘agricultural transition’ is completed, the UK experience is likely to define the parameters of debate on future agricultural policy in the EU. If the UK experience is deemed a success, advocates of reform of agricultural support under the CAP will for the first time have a relevant role model (the New Zealand experience of agricultural policy reform in 1984 being of very limited relevance). If it is deemed a failure, advocates of the need to maintain strong public support for farm incomes will be confirmed in their views.

Some might argue that, regardless, England is also not a very relevant example for much of EU agriculture. The average farm size is 85 hectares, which is well above the average farm size in the EU of 16 hectares, although just over a third of all holdings are less than 20 hectares. The structure of holdings is very skewed. In 2016, just 7% of farm holdings produced 55% of agricultural output, using just 30% of the total farmed land area.

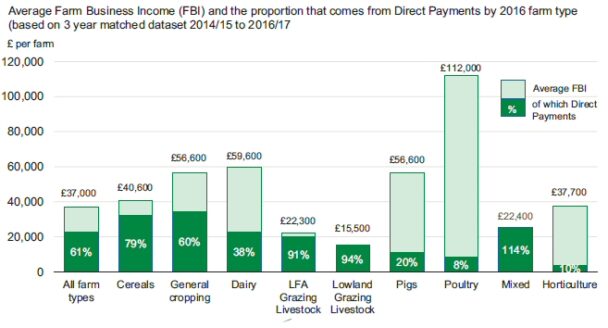

Nonetheless, the dependence of farm income on direct payments is at least as great as in the rest of the EU. Across all farm types, 61% of farm business income came from direct payments over the period 2014/15 to 2016/17, with grazing livestock and mixed farms the most dependent. Over the same period, 16% of farms made a loss with direct payments. Removing them would have meant 42% of farms would have made a loss, ignoring adjustments such as lower investments and rents which would be expected to offset some of the impact.

Eliminating direct payments over a relatively short time period, even if some (most?) of the money saved is recycled into payments for public goods, will be a major shock to English agriculture. How will it react? Success or failure will, of course, mean different things to different people. Where one person will celebrate structural adaptation which leads to improved competitiveness, another will lament the disappearance of smaller farms. The experiences gained

if the UK goes ahead and implements its proposed policy vision in England will provide invaluable data on the impact of reform, but it will certainly not end the debate on how best to design agricultural policy.

Update 29 March 2018: Post has been updated to take account of Article 130(1) in the version of the draft Withdrawal Agreement agreed by negotiators on 19 March 2018 which provides that the CAP direct payments regulation will not apply in the UK in claim year 2020.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Thank you, Alan. A really interesting comparison.

It seems to me that there are two huge challenges to the agricultural system, one worldwide, the other local, which are rarely considered by UK politicians, and some further afield:

Worldwide, it’s difficult to make a living from primary production, which is one of the reasons why farmers are, by and large, an elderly community.

You make this point re the EU: “Across all farm types, 61% of farm business income came from direct payments over the period 2014/15 to 2016/17, with grazing livestock and mixed farms the most dependent. Over the same period, 16% of farms made a loss with direct payments. Removing them would have meant 42% of farms would have made a loss, ignoring adjustments such as lower investments and rents which would be expected to offset some of the impact.”

If people can’t make a living from primary production, we either have to have subsidies of some kind, or prices must rise — otherwise we don’t have a food system.

The second challenge is that four out of five countries globally rely on food imports for their supply (see this Chatham House report: https://resourcetrade.earth/stories/chokepoints-and-vulnerabilities-in-global-food-trade?_ga=2.215388439.1872305081.1514388043-2000522538.1512231317%23section-131).

Climate change, resource depletion and population pressures will put even more pressure on the global food system.

As for the UK, when local harvests are good, we import 40% of the food we eat. Estimates suggest this will rise to 50% if a hard brexit happens.

Given the pressures on the global food system, it’s unwise to assume that the UK can depend on importing sufficient, safe, nutritious food in the future, without paying much more for it — with all the social consequences that would mean.

How much of a food security risk there is in reducing or eliminating direct payments of one kind or another to farmers is rarely considered. And, I would argue, it should be.

@Kate, many thanks for thoughtful comments. There are no right answers to the two issues you raise, certainly not in two lines, but I would add the following points.

When you say that there are only two choices in a situation where farmers cannot make money if we want to have a food system . either we provide subsidies or prices must rise – you may underestimate the extent to which production costs differ across farms, particularly in different size groups. You may hear from many of the farmers you meet that they cannot make ends meet on the basis of market prices alone,but, although numerous, their contribution to the overall food supply may not be that significant. Look at the figures for England that I quote in the post – just 7% of farms supply 55% of total food supply. My expectation is that most of these farms probably have sufficient scale that they are doing fine. As a citizen and consumer, you may regret that farms need to get bigger to survive, and that is a valid debate to have.But it suggests that the argument that primary production does not make money needs to be nuanced.

Similarly, every country needs to consider its food security, but relying on imports is not necessarily inappropriate. You raise a concern that, with growing pressures on food production systems worldwide, global food prices will rise and reliance on imports will become more expensive. Of course, if this were to happen, this would automatically improve the profitability of domestic production as well and would stimulate an appropriate supply response. Forecasts, of course, are not fool-proof, but it is worth noting that, along with the warning signs on production constraints (limited land, water, soil degradation and climate risks), the global demand for food is slowing sharply (see https://voxeu.org/article/demand-agricultural-commodities-grow-more-slowly-next-decade), so official forecasts (e.g. OECD-FAO) do not foresee a sharp jump in food prices in the medium term. This does not exclude the possibility of temporary interruptions in food supplies, due to logistical difficulties etc. Food stocks (such as the Swiss maintain) may be a justified measure in an importing country in that situation.