The land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector is assigned an important role in both global and EU climate policy because it is an important store of carbon (around four times as much carbon is stored in soils and biomass including forests as in the atmosphere itself (Lal, 2004) and it is, to date, the only sector with the large-scale potential to sequester carbon from the atmosphere.

The Paris Agreement highlights the potential contribution of the LULUCF sector by setting an objective to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century in order to meet its overall goal of holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Under the EU’s climate regime to 2020, the LULUCF sector does not count towards the EU’s domestic 20-20-20 targets. However, it is counted towards determining whether the EU is meeting its targets under the Kyoto Protocol’s second commitment period 2013-2020.

In October 2014 the European Council conclusions on the climate and energy framework for 2030 stated that “Policy on how to include Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry into the 2030 greenhouse gas mitigation framework will be established as soon as technical conditions allow and in any case before 2020.”

Subsequently, the Council and Parliament have agreed on various pieces of legislation which set the framework for how emissions from the LULUCF sector will be measured and monitored and the role they will play in meeting the EU’s 2030 targets. The main pieces of legislation include Regulation 2018/841 on the inclusion of greenhouse gas emissions and removals from land use, land use change and forestry in the 2030 climate and energy framework (the “LULUCF Regulation”) and Regulation 2018/842 on binding annual greenhouse gas emission reductions by Member States from 2021 to 2030 (the “Effort-Sharing Regulation”). The LULUCF sector is also covered by Regulation 2018/1999 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (the “Governance Regulation”) which sets out a requirement for Member States to develop long-term strategies with a perspective of at least 30 years contributing to the fulfilment of Member States’ commitments under the United National Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement.

I had previously written about the options for including the LULUCF sector in the EU’s climate regime for 2030 back in 2015. Clearly, a lot has changed since then. This post summarises the current state of play following these legislative decisions. The treatment of the LULUCF sector has important policy implications for the interpretation of the EU’s long-term strategy towards net-zero emissions, for the ability of Member States to use LULUCF credits towards meeting their national emission reduction targets in the sectors not covered by the Emissions Trading Scheme and vice versa, and for the EU’s ability to meet its renewable energy targets from domestic biomass. I plan to look at these policy issues in later posts.

The crucial distinction between reported and accounted LULUCF emissions

In preparing inventories of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and removals for submission to the UNFCCC, countries are asked to report on anthropogenic emissions and removals, meaning emissions and removals that are the result of human activities. In the LULUCF sector, emissions and removals on managed land are taken as a proxy for anthropogenic emissions and removals. Thus, UNFCCC reporting covers all emissions by sources and removals by sinks from managed lands, considered to be anthropogenic, while emissions and removals for unmanaged lands are not reported. This approach was decided in the absence of a practicable methodology that would factor out direct human-induced effects from indirect human-induced and natural effects for any broad range of LULUCF activities and circumstances.

However, when it came to setting targets in the Kyoto Protocol, it was decided that only some of these emissions and removals should be accounted with respect to commitments. The accounting is done through policy agreed accounting rules, which filter the reported estimates with the aim to better quantify the results of mitigation actions. The LULUCF accounting produces ‘debits’ or ‘credits’ (i.e. extra emissions or extra emission reductions, respectively) that count toward the target.

Through the debit and credit system, the aim is to provide incentives for beneficial actions and policies, or disincentives for detrimental actions, by excluding changes in carbon stocks due to actions prior to the start of the compliance period. For example, some countries claimed that an unavoidable declining sink (e.g. due to ageing forests) should not be treated as a debit as long as sustainable management is ensured. The accounting rules are intended to remove the legacy effects of past management decisions to better measure the results of actions that countries take either to reduce emissions or safeguard sinks on managed land.

Policy based accounting rules can take various forms in attempting to capture mitigation efforts relative to some counterfactual or base value:

- Gross-net accounting means accounting for the actual (gross) reported emissions or removals from a specific land use category. LULUCF debits and credits are equal to reported emissions and removals in the UNFCCC inventories. Here the counterfactual value is set at zero.

- Net-net accounting is where debits and credits are calculated relative to a counterfactual value set as the emissions of a base year. Debits are incurred when net emissions increase relative to the base period, while credits are gained if net emissions decrease. In contrast to gross-net accounting, it is only the change in emissions/removals that counts.

- Reference level accounting is a special form of net-net accounting where actual emissions and removals in a given year are compared against a projected reference level.

This distinction between reported emissions (recorded in the UNFCCC inventory submissions) and accounted emissions (used for the purpose of determining compliance with a target) is central to understanding discussions of the significance of LULUCF emissions in the EU and how they are treated in the climate regime. When looking at LULUCF time series, it is vital first to check whether the series refers to emissions/removals (reported emissions) or debits/credits (accounted emissions). Its complicated!

LULUCF accounting rules in the 2021-2030 period

The policy agreed accounting rules evolved through the first and second commitment periods of the Kyoto Protocol (see this UNFCCC web page) and have been further revised in the EU’s 2018 LULUCF Regulation. The key elements that will apply in the 2021-2030 period are as follows:

- Six accounting categories are included in the agreed approach: afforested land, deforested land, managed cropland, managed grassland, managed forest land and managed wetland. Harvested wood products are taken into account both in the afforestation and managed forest land categories. Unlike under the Kyoto Protocol, the accounting categories are now aligned with UNFCCC reporting for land use categories and the conversion between land use categories. Deforested land (land converted from forest to other uses) is not directly reported in the UNFCCC inventories (it is reported in the land use category to which the land is transferred) but is required to be separately accounted under the LULUCF Regulation.

- All categories except managed wetland are mandatory to include in the accounts. Wetlands are to be included from 2026.

- A 20 years conversion period should be used for land use changes. An exception is the afforested land category, for which a 30 years conversion period can be used if duly justified based on the IPCC Guidelines.

- Two commitment periods are distinguished, 2021 to 2025 and 2026 to 2030. This means that LULUCF accounting is in principle not based on annual but on multi-year accounts.

- Emissions and removals from afforested and deforested lands are accounted in full (gross-net accounting).

- Emissions and removals from managed cropland, grassland and wetland are compared in each five-year commitment period to net emissions and removals in a base period defined as 2005 to 2009 (net-net accounting).

- Emissions and removals from managed forest land are compared to a forest reference level (FRL). FRLs should be based on the continuation of sustainable forest management practice, as documented in the period from 2000 to 2009 with regard to dynamic age-related forest characteristics in national forests. In addition, FRLs should take account of the future impact of dynamic age-related forest characteristics in order not to unduly constrain forest management intensity as a core element of sustainable forest management practice, with the aim of maintaining or strengthening long-term carbon sinks.

- Certain emissions resulting from natural disturbances can be excluded from the accounts for afforestation and managed forest land (but not from agricultural soils). Only emissions resulting from natural disturbances exceeding the average emissions caused by natural disturbances in the period 2001-2020 can be excluded from the accounts.

LULUCF commitments in the 2021-2030 period

The principal commitment for the Member States is to ensure that the LULUCF sector shall not create debits in either of the two commitment periods 2021-2025 and 2026-2030 (‘no-debit rule’ set out in Article 4 of the LULUCF Regulation). However, there are various flexibilities in the way credits and debits can be combined to demonstrate compliance with this commitment, as well as linkages between the accounted outcome under the LULUCF Regulation and emissions reduction targets under the Effort-Sharing Regulation.

- Intra-LULUCF flexibility. Debits incurred in one land use can be offset by credits obtained in another land use in assessing compliance with the no-debit rule. The only exception is that there is a cap on potential credits from managed forest land that can be used in this way. The net removals from managed forest land entered into the accounts cannot exceed 3.5% of the emissions of that Member State in its base year multiplied by five. Net removals due to dead wood and harvested wood products are not included under this cap.

- Banking flexibility. A Member State with credits in the first commitment period can transfer these credits to the second commitment period.

- Intra-MS flexibility. Member States with credits can transfer these credits to another Member State.

- Managed forest land flexibility. If a Member State has a debit summed over all land use categories in a commitment period, it can make use of a compensation mechanism in the managed forest land category under specified conditions. These are that the Union as a whole cannot be in net debit and that the Member State has undertaken specific measures to conserve or enhance forest sinks. The mechanism allows Member States to reduce their debits by individual amounts set out in an Annex to the LULUCF Regulation. An additional compensation allowance is made available to Finland of 10 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions on top of the 44.1 million tonnes it was granted under the standard allowance.

There is a two-way linkage between net debits/credits under the LULUCF Regulation and a Member State’s emissions targets under the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR).

- A LULUCF credit position can be partially used to offset emissions under the ESR, up to a maximum of 280 million tonnes CO2 equivalent for the EU as a whole over the period 2021-2030 (this number will be reduced by 17.8 million tonnes when the UK leaves the Union). The purpose of this flexibility is to acknowledge the lower mitigation potential of the agriculture sector covered by the ESR. The flexibility is distributed among Member States related to the significance of agricultural emissions in their total ESR emissions. In calculating the LULUCF credit position for the purpose of this offset, currently the credit/debit position of managed forest land is not included. However, when the Commission adopts delegated acts to update the forest reference levels (see below), it is empowered to adopt a delegated act to include net removals from the accounting category managed forest land and, eventually, managed wetlands, into the flexibilities (Art 7 of the ESR Regulation). These credits can be used towards compliance where a Member State’s emissions in the ESR sectors exceed its annual target in any year over the 2021-2030 period. Given that the LULUCF accounting will be done on five-yearly intervals, it is not clear to me how this credit offset system will work with annual ESR targets.

- A LULUCF debit position must be accounted towards the ESR target of a Member State. If a Member State after making use of the LULUCF flexibilities has a debit position in either commitment period, that debit amount will be deducted from its ESR annual emission allocations for the relevant years (although the preamble refers to this as a voluntary option for Member States, the text of the ESR Regulation makes clear there will be nothing voluntary about it). This will tighten its ESR targets and require greater emissions reductions from the ESR sectors to meet these tighter targets (Art 12 of the ESR Regulation).

Establishing the Forest Reference Levels (FRLs)

Setting the FRLs for each Member State is a necessary step to allow for the calculation of credits or debits from managed forest land during the two commitment periods. As noted, the justification for this approach is to provide a baseline to show how the forest would develop if no changes to policies or practices were put in place (i.e. the counterfactual value).

If the forests had a relatively large share of trees in a certain age class, the total harvest would fluctuate over time purely because there are different amounts of trees reaching the harvest age. The use of a FRL attempts to capture only the impacts of changes in forest management practices, relative to practices under a historical reference period, and to eliminate the differences that result purely from age-related dynamics and other ‘exogenous’ developments in the forest stock.

The reference level approach was introduced in the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol (2013-2020). The way in which reference levels (then called Forest Management Reference Levels, FMRLs) were calculated by Member States at that time did much to bring the whole reference level approach into disrepute. Member States made different assumptions in calculating their FMRLs, and they took into account planned policy changes as well as historical practices. This led to very generous reference levels which has resulted in a flood of ‘credits’ when actual removals turned out to be much less than projected in the FMRLs.

The Commission was determined that the FRLs for the two commitment periods between 2021-2030 would be developed in a more robust manner. It was not only concerned to avoid the generation of unwarranted removal units. It was also concerned with the environmental credibility of the accounting conventions for biomass used for renewable energy purposes. Under Kyoto Protocol rules (carried over into EU legislation) the combustion of biomass counts as zero in the energy sector while the resulting carbon stock changes are accounted as emissions in the LULUCF sector. This avoids double counting of emissions.

But in the EU’s 2020 climate regime debits/credits in the LULUCF sector are not taken into account. Even if they were accounted for, as will be the case from 2021 onwards, if the accounting rules for managed forest land do not fully reflect removals of biomass for renewable energy, the accounts become leaky and the framework becomes unbalanced (Commission LULUCF Regulation Impact Assessment). The outcome wanted is that the FRLs would generate close to zero removal units/debits in the absence of significant change in the forest harvest practices (unless such change is justified by the age-class structure and other national forest characteristics).

The LULUCF Regulation tries to do this by specifying more clearly how the FRLs should be determined solely on the basis of historical practices. Parameters defining the forest management practice (e.g. rotation lengths, rates of harvest in ‘thinnings’ and ‘final cuts’, for a given forest species, etc.) during the reference period should be documented and be kept constant in the projection. Assumed future impact of policies or market development are not to be included in the estimation of the FRL. At the same time, the projected FRL should be consistent with ‘the aim of maintaining or strengthening long-term carbon sinks’. The Commission prepared a set of detailed guidelines on interpreting the criteria set out in the Regulation for preparing the national forest accounting plans including the forest reference level to assist Member States. This was not a binding document and it was at the discretion of each Member State to use or not use the document when establishing their national FRL and accounting plan.

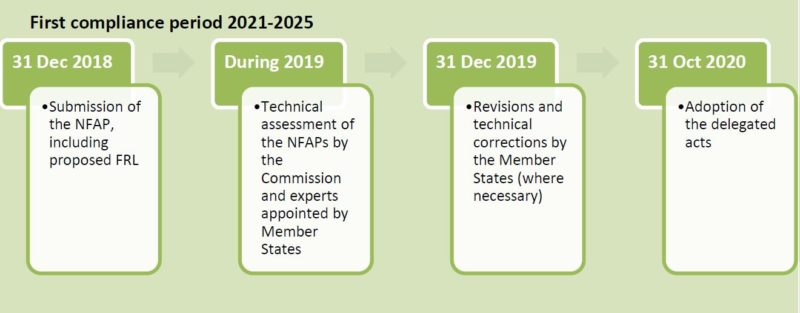

The LULUCF Regulation also put in place a governance mechanism designed to challenge and test the assumptions behind the modelling of the FRLs undertaken by the Member States. Member States were required to submit their national forestry accounting plans, including a proposed FRL, to the Commission by 31 December 2018 for the period from 2021 to 2025 (and by 30 June 2023 for the period from 2026 to 2030). The Commission, in consultation with experts appointed by the Member States, would then undertake a technical assessment of the national forestry accounting plan during 2019, also consulting stakeholders and civil society and the results of the technical assessment would be published. Subject to the technical assessment and any subsequent revisions, the FRL for 2021 to 2025 would then be adopted by delegated act by 31st October 2020. The following diagram illustrates the procedure set out in the Regulation.

Timeline for preparation of Forest Reference Levels (FRLs) in National Forest Action Plans (NFAPs)

Source: Fossell et al., 2018

Following this process, the Commission established an expert group including representatives from Member States, technical specialists, NGOs and research organisations, representatives of Norway, Iceland and the EFTA Surveillance Authority, and observers from various interested stakeholder groups to assess the plans. Following meetings in Brussels on 6 February and during 1 April to 12 April 2019, the expert group adopted its synthesis report conclusions on the national plans. The synthesis reports highlighted areas where the transparency and accuracy of the assumptions behind the FRLs might be improved, but the changes sought are relatively minor and the accounting plans and FRLs seem to be broadly consistent with the spirit of the Regulation. The Commission’s own assessment concluded that “The resulting technical recommendations … reflect the generally high quality of the submitted plans while pointing to some country-specific approaches that will require further careful analysis”.

The technical assessment process and the conclusions of the expert group served as a basis for the technical recommendations for improving the national plans which were made by the Commission earlier this month. Member States must now submit their revised forest reference levels based on the synthesis report conclusions and technical recommendations by 31 December 2019. The Commission will then publish the FRLs in a delegated act before 31 October 2020, and will at the same make a determination whether credits from managed forest land can count towards offsets in the ESR sector.

In summary, the rules for accounting for LULUCF debits and credits in the 2021-2030 period are now in place. Once the FRLs are finally established for the first commitment period, Member States will be better able to evaluate the policy implications of the ‘no-debit’ target they have to meet. These policy implications will be the subject of later posts.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Picture credit: Pxhere under a Creative commons licence

Thanks for bringing some much need clarity to such a complex subject, and for confirming and adding to my own understanding.

Maybe you will cover it in a future post but scanning the EC-WG analysis for Ireland’s FRL submission does not echo the rosy view of the EC overall. Ireland’s policy focus is constantly directed toward afforestation rates yet the EC-WG point to the equally important issue of harvest rates vs. “forest biomass decline as the lack of full understanding could undermine the credibility of Ireland’s FRL.” The WG also point out that Ireland’s FRL submission is not consistent with the latest submission of the National Inventory Report (NIR). The latter, using updated and more accurate modelling shows an even more rapidly declining overall forest sink, worryingly, to being a net emitter by 2030.

However accounted, in Ireland it looks like over-harvest relative to growth is at least as much a problem as lower than planned afforestation. Given projected increases in harvest for bioenergy it would look like there are reasons for concern for maintaining and increasing Ireland’s standing forest carbon stock, which, scientifically, is its actual climate mitigation value.

@Paul

These are important points, and they do not only apply to the Irish FRL. The overall forest sink in the EU as a whole is expected to decline between now and 2050, and whether this is mainly due to the age-related dynamic or mainly to increased harvesting seems disputed. It is also not clear how the Commission interprets the criterion that “The reference level shall be consistent with the goal of achieving a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century…” as the phrase “anthropogenic emissions” could allow for reductions in the sink due to age-related dynamics. I’m not sure how to interpret the point about ‘over-harvesting’ as Irish plantation forests tend to be clear-felled on a strict silvicultural rotation where demand factors play only a very limited role, which the national accounting plan explains.