The CAP Communication was published by the Commission on 29 November last. In a previous post, I commented on an early leaked draft of this Communication. A number of changes in emphasis were added in the final version but the basic structure of the proposal has not changed. It is nonetheless worth to revisit the document and the Commission’s suggested vision for the direction of the CAP after 2020.

Much of the initial reaction both in the meeting of the European Parliament’s AGRI Committee to which Commissioner Hogan presented the Communication on the day of its publication (the video can be watched here) and at the December meeting of the AGRIFISH Council where Agriculture Ministers had their first chance to discuss the document (the discussion was held in private session but Vice President Katainen’s speaking notes are available and the subsequent press conference can be viewed here) focused on the proposed new delivery model for the CAP. I leave a detailed discussion of the new delivery model to a future post. In this post, I want to summarise the main themes in the Communication and speculate on what it might mean for the future structure of the CAP.

Restating the CAP’s objectives

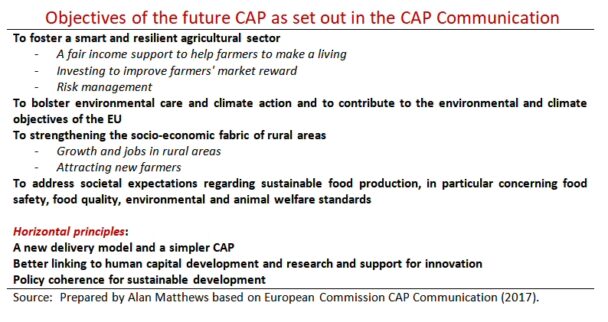

The vision for the CAP after 2020 set out in the Communication has been described by Commissioner Hogan as an evolution rather than a revolution. Four objectives for the CAP are identified in the Communication (see table). The first three of these replicate the CAP objectives for the 2013 CAP reform and the fourth gives greater visibility to consumer and citizens’ interests in food and farming.

The four objectives are: a smart and resilient agricultural sector (updating ‘viable food production’); bolstering environmental care and climate action (updating ‘sustainable management of natural resources and climate action’); and strengthening the socio-economic fabric of rural areas (updating ‘balanced territorial development’). A fourth objective to address societal expectations regarding sustainable food production, in particular concerning food safety, food quality, environmental and animal welfare standards, has been added. This is a welcome and potentially far-reaching recognition that not only farmers but also consumers and citizens have legitimate interests in shaping the future of the CAP, although it is also recognised that the CAP is just one of the EU policies which are relevant to achieving these outcomes.

These four objectives are underpinned by three horizontal measures or principles which apply to each objective. The first is the proposal for a new delivery model for the CAP and a commitment to a simpler CAP. The second is the need for a shift towards a more knowledge-based agriculture based on research and innovation. And third, there is an explicit recognition that the measures implemented to achieve the CAP objectives should be coherent with the Union’s commitment to supporting sustainable development in developing countries. In this post, we concentrate on the objectives set out for the CAP after 2020.

A fair income support to help farmers to make a living

The Communication makes clear that area-based decoupled direct payments to farmers will continue as “an essential part of the CAP in line with its EU Treaty obligations”. It notes that “Direct payments currently shore up the resilience of 7 million farms, covering 90% of farmed land. While they make up around 46% of the income of the EU farming community, the proportion is much higher in many regions and sectors. They thereby provide relative income stability to farmers facing significant price and production volatility – which helps to keep the EU’s vital high-quality food production base spread around the Union”.

Whether area-based direct payments are an efficient and effective way of achieving these objectives is contested (see my contribution to the RISE Foundation CAP: Thinking out of the box report). Making reference to the Commission’s Reflection Paper on the Future of EU Finances, the Communication acknowledges that direct payments could be targeted more effectively to ensure income to all farmers across the EU. It identifies a number of options which could be explored “in order to ensure a fair and better targeted support of farmers’ income”:

• A compulsory capping of direct payments taking into account labour to avoid negative effects on jobs;

• Degressive payments could be introduced as well, as a way of reducing the support for larger farms;

• Enhanced focus on a redistributive payment in order to be able to provide support in a targeted manner e.g. to small-medium sized farms;

• Ensure support is targeted to genuine farmers, focussing on those who are actively farming in order to earn their living.

In its original proposals for the 2013 CAP reform, the Commission proposed to introduce capping (albeit only the basic payment/single area payment would be capped, capping would be applied only to payments over €300,000, and gross salary payments would be taken into account as an offset before capping would be applied). Degressivity at rates between 20% and 70% would be applied to payments between €150,000 and €300,000. In the event, mandatory degressivity was introduced to a much more limited extent (at the rate of a reduction of 5% in the value of basic payments/single area payments over €150,000 after possibly deducting the value of salaries paid) in the 2013 CAP reform (though Member States that made significant use of the redistributive payment were exempted from having to apply it).

However, Member States could voluntarily increase the degressivity percentage up to 100% (which is a de facto cap or ceiling on the absolute size of payment per farm). So this idea in itself is not new, although its implementation to date shows that it has been quite ineffective. The product of degressivity and capping together in the 2015 claim year amounted to 0.44% of the basic payment, or 0.25% of the entire Pillar 1 direct payments ceiling. Only a minority of Member States introduced the redistributive payment in the 2014-2020 CAP period.

In the earlier leaked draft of the Communication, the Commission had suggested a compulsory capping (after taking account of salaries paid to avoid a negative effect on jobs) at around €60,000-€100,000, which would potentially raise a larger sum of money. However, no mention of a specific ceiling is retained in the final Communication.

The proposal to confine support to active farmers was a major focus of debate in the last CAP reform, but gave rise to so much additional paperwork for Member State paying agencies that they successfully pleaded for a relaxation of the requirements to define an active farmer when political agreement was reached on the Omnibus Regulation in October 2017. This distinction between active and non-active farmers now becomes optional, allowing Member States to discontinue it. In the light of these developments, whether there will be greater political will to adopt more stringent limits on who is entitled to direct payments on the next occasion remains to be seen.

Investing to improve farmers’ market reward

The idea here is that the CAP should play a larger role in helping farmers make more money from the market. Three issues are identified under this heading:

• boosting investments into farm restructuring, modernisation, innovation, diversification and uptake of new technologies and digital-based opportunities such as precision agriculture, the use of big data, and clean energy.

• Improving the position of farmers in the food chain. Much of the debate here is around strengthening the role of recognised producer organisations to enable farmers to strengthen their bargaining position in the value chain and to cooperate to reduce costs and to improve their competitiveness to improve market reward.

• finally, policy should focus more on support the efforts of farm businesses to link up with emerging sustainable rural value chains in areas such as bio-based industries, bio-energy and circular economy, as well as ecotourism.

The Communication also identifies the need to address the current investment gap in agriculture through more use of innovative financial instruments that take into account the specificities of farming, as well as more integrated projects that link various EU instruments (European Fund for Strategic Inestments, European Structural and Investment Funds).

The emphasis on encouraging the uptake of new technologies and the use of digitalisation is welcome (see this EIP-AGRI Factsheet on shaping the digital revolution in agriculture for examples and case studies). The Commission is clear that for many farmers this will remain a pipe-dream until high-speed internet access is consistently and reliably available across all rural areas. New business models as well as clarity around the rules on data sharing will be necessary before the full potential of these technologies can be exploited.

Already, in the Omnibus Regulation, measures to strengthen the role of producer organisations in the food chain have been agreed. The Commission is also committed to bringing forward legislation to address unfair trading practices and to improve the EU food supply chain early next year. While greater transparency around the role of contracts in the supply chain is needed, I am sceptical that the likely benefits to farmers will be commensurate with the amount of effort put into this by the farm organisations and their supporters. Thus, broadening the issue to supporting farmers in establishing value added activities by linking up with rural value chains as well as improving productivity makes good sense in my view.

Risk management

The Communication advocates setting up “a robust framework for the farming sector to successfully prevent or deal with risks and crises, with the objective of enhancing its resilience and, at the same time, providing the right incentives to crowd-in private initiatives”. It notes that “the CAP already offers a layered set of tools helping farmers to prevent and manage risks, from direct payments and market intervention to post-crises compensations and the present second pillar measures in particular an Income Stabilisation Tool (IST) and insurance support” and suggests exploring “how existing possibilities as regards risk management can be better exploited”.

However, its proposals under this heading can be seen as tentative. It proposes to set up a permanent EU-level platform on risk management, which would provide a forum for farmers, public authorities and stakeholders to exchange experiences and best practices, with the objectives of improving implementation of the current tools and informing future policy developments. It also suggests exploring how to further develop an integrated and coherent approach to risk prevention, management and resilience, which combines, in a complementary way, EU-level interventions with Member States’ strategies and private sector instruments which address income stability as well as climate risks.

There are no specific suggestions for new instruments, although it advocates examining the use of indexes to calculate farm income losses as a way of reducing red tape and costs. However, the Omnibus Regulation has introduced a new sector-specific income stabilisation tool. It has also reduced the income drop to trigger support in this new tool from 30% to 20%, and in addition support for insurance contracts will now be given in cases where production losses are greater than 20% rather than the 30% previously. These changes will increase the attractiveness of these risk management instruments, though Member States must first decide to include them in their Rural Development Programmes.

This section of the Communication has been criticised by those who wish to return to a greater degree of market regulation. There is no specific mention of the proposal for a voluntary production reduction scheme which was favoured by the Parliament in the debate on the Omnibus Regulation though ultimately not included in the final agreed legislation. There are no proposals to revisit the crisis reserve which clearly did not fulfil its function during the commodity market difficulties in recent years. The Commission mobilised €1.5 billion in additional funds without resorting to this reserve, and there must be doubt that this favourable budget situation can be replicated in the future. The Parliament’s AGRI Committee will likely push for more attention to these issues in its own-initiative report on the Communication.

Bolster environmental care and climate action and contribute to the environmental and climate objectives of the EU

Although this is already a specific objective of the CAP (under the rubric of ‘sustainable management of natural resources’), the Communication insists that this objective will have greater priority in the CAP after 2020. It recognises that “farmers and foresters are not only users of natural resources, but also, indispensable managers of ecosystems, habitats and landscapes. Any new CAP should reflect higher ambition and focus more on results as regards resource efficiency, environmental care and climate action”.

Here, the Communication proposes to replace the current green architecture of the CAP, that primarily relies on the complementary implementation of three distinct policy instruments – cross compliance, green direct payments and voluntary agri-environmental and climate measures) and to integrate all these operations into a more targeted, more ambitious yet flexible approach. Specifically, this means that there will not be a “greening” scheme as we know it today, which has proven to be complex to implement and administer. However, the granting of income support to farmers would continue to be conditioned to their undertaking of environmental and climate practices, which will become the baseline for more ambitious voluntary practices. This seems to confirm a continued role for cross-compliance.

Additional environmental/climate benefits will be achieved through voluntary entry level schemes and more ambitious agro-environment-climate schemes that will allow Member States/regions to target their specific concerns. The new delivery model will allow Member States to devise a mixture of mandatory and voluntary measures in Pillar I and Pillar II to meet the environmental and climate objectives defined at EU level. Given this proposed architecture, it would seem to be left up to Member States to decide if the existing greening conditions (particularly Ecological Focus Areas) would continue to be implemented and, if so, how they would be implemented and defined (for example, will they be moved into cross-compliance or become part of the voluntary entry level schemes?).

There is a huge disconnect in the Communication between the insistence that environmental and climate objectives will be given greater priority in the new CAP and the lack of any specific commitments in this section of the Communication which might deliver on this aspiration. The new delivery model is defended as leading to simplification but this, in itself, does not guarantee higher ambition.

The only way in which higher environmental and climate ambition might be stimulated is in the setting of the agreed environmental and climate targets at EU level which the Member States will be asked to meet when drawing up their CAP strategic plans. But there is no discussion of what these targets might be, and no discussion of the scale of the challenge that needs to be addressed to put European agriculture on a more sustainable path. Given the rhetoric used by both Vice-President Katainen and Commissioner Hogan when presenting the Communication that the question of sustainability has to be at the heart of the policy, this rather skimpy section of the Communication is a disappointment. It will need considerable beefing up in the coming months if the Commission’s rhetoric is to be taken seriously.

Strengthening the socio-economic fabric of rural areas

The Communication recognises that many rural areas in the EU continue to suffer from structural problems such as a lack of attractive employment opportunities, skill shortages, underinvestment in connectivity and basic services and a significant youth drain. It asserts that new rural value chains such as clean energy, the emerging bio-economy, the circular economy, and ecotourism can offer good growth and job potential for rural areas. It proposes that the bio-economy in a sustainable business model should therefore become a priority for the CAP strategic plans foreseen in the new delivery model, and support the EU circular economy strategy.

The Communication also proposes that generational renewal should become a priority in a new policy framework. It sensibly recognises that Member States are in the best position to stimulate generational renewal using their powers on land regulations, taxation, inheritance law or territorial planning. Nonetheless, it identifies a need to improve the consistency between EU and national actions, advocating that the CAP should give flexibility to Member States to develop tailor made schemes that reflect the specific needs of their young farmers. However, the Communication is silent on the barriers that the CAP itself through its direct payments creates for generational renewal by pushing up the price of land out of the reach of new entrants, while also incentivising older farmers, who are often also in receipt of national pension payments, to hold on to their land in order to draw down CAP payments as well.

Addressing citizens’ concerns regarding sustainable agricultural production, including health, nutrition, food waste and animal welfare.

The Communication underlines that the CAP is one of the EU policies “responding to societal expectations regarding food, in particular concerning food safety, food quality, environmental and animal welfare standards”. While the issues covered in this section of the Communication are not new, it is the first time they have been explicitly recognised as an objective of the CAP. They include issues of food quality (support for organic production, for local specialities and for improved animal welfare), food safety (tackling antimicrobial resistance and supporting the Sustainable Use of Pesticides directive), sustainable food use including reducing food waste, and healthier nutrition (where the Schools schemes which subsidise free fruit, vegetable and dairy products are highlighted, and campaigns to promote healthy dietary practices and increase the consumption of fruit and vegetables are advocated as a focal point in future CAP promotion activities).

The Communication does not go so far as to call for a common agricultural and food policy (a behemoth I would not wish on anyone) and it remains to be seen how this fourth objective will be reflected in concrete policies. One way to show seriousness of intent on this objective would be to ensure that citizens other than farmers and their representatives on the AGRIFISH Council and the AGRI Committee of the Parliament get an equal chance to influence, debate and decide on the future legislative proposals.

Conclusions

This Communication on the future of the CAP sketches out a vision for the direction of travel. The emphasis on the need for a greater level of environmental and climate ambition in the CAP post 2020, the proposal for a more results-based approach to the delivery of CAP objectives, as well as the call to strengthen the knowledge base for farming through more research and innovation as well as stronger farm advisory services, are all welcome proposals.

But there are clearly many unanswered questions, particularly with respect to how the new delivery model would work in practice. While the proposal to move away from a prescriptive approach towards giving Member States greater flexibility in the design of CAP instruments has been generally welcomed, we have doubts that the monitoring and auditing of Member State targets can be sufficiently robust to ensure a higher level of environmental and climate ambition which the Communication accepts is necessary. In particular, the Communication is silent on the nature of the sanctions, if any, that might accompany the failure of a Member State to meet its targets.

The Communication is also silent on the budgetary implications of its proposals. It recalls that the Commission’s Reflection Paper on the Future of EU Finances identified a number of new challenges for which the EU budget will need to do more than today. It goes on to note: “In this context, all existing instruments including the CAP will need to be looked at. Hence, this Communication does neither pre-empt the outcome of this debate nor the proposals for the next multiannual financial framework (MFF)”. This silence on budgetary implications is not surprising as the budgetary framework for the future CAP will be decided as part of the European Council conclusions on the next MFF and not within the framework of revisions in the CAP regulations.

The Communication proposes to maintain the two-pillar CAP structure, in which direct payments to farmers and market support measures are funded by Pillar 1 and rural development including environmental and climate actions are funded by Pillar 2. There is no explicit indication given whether the balance between the two Pillars (currently in the ration 75:25) will be altered. The Communication underlines that currently 46% of farm income within the EU is derived from Pillar 1 payments (and, for particular farm systems such as grazing livestock, this share increases to 70%). It does not give a view on whether this dependence on support is either desirable or sustainable.

The Communication accepts that the greening payment in Pillar 1 (which accounts for 30% of direct payments) has not been a success and will be eliminated, but it is not explicit whether this funding will be moved to Pillar 2 although that would seem to be the logic of its new architecture. Other proposals in the Communication (more support for farm investment, for new technologies, for farm advisory services, for risk management, for new entrants and to help farmers meet societal expectations) would also require additional funding for Pillar 2 programmes even if the sums involved might not be that large. Though, at least with respect to the investment gap, the Commission has identified the use of innovative financing instruments provided by the banking sector as one way to proceed.

If it is necessary to make savings in Pillar 1 of the CAP, either to shift resources to give greater priority to Pillar 2 programmes or to fit within a more limited overall CAP budget ceiling in the next MFF period, the Communication hints at two mechanisms. One is national co-financing of Pillar 1 payments, which are currently 100% financed by the EU budget. This suggestion was aired in the Commission Reflection Paper. It was explicitly ruled out in the leaked draft of the Communication, but this explicit rejection has been removed from the final version, suggesting that it may still be in play in the MFF discussions. The potential significance of national co-financing in reducing the demands for CAP financing in the next MFF would depend on the co-financing rate that was agreed, and whether this would be differentiated across Member States or by type of expenditure. National co-financing of Pillar 1 expenditure is strongly opposed by farm organisations, many Member States and various political groups.

The other mechanism that could potentially release Pillar 1 money for additional Pillar 2 programmes is degressivity and capping of Pillar 1 payments to larger beneficiaries. We noted earlier that this approach to facilitating transfers to Pillar 2 has not been effective in the current CAP period. Opposition to degressivity and capping can be expected to continue from those Member States which have large farm structures (mainly those that have inherited dualistic farm structures from their experience of collectivisation under Soviet influence). One possible way forward would be to combine the principles of national co-responsibility, European value added and better targeting of direct payments by, at a minimum, withdrawing EU budget support for income payments to larger beneficiaries.

The Communication has to speak to many audiences and thus it is no surprise that it is a bit like a curate’s egg. Although it repeats some well-worn nostrums that are well past their sell-by date, it also embraces some forward-looking elements which deserve support. But there is a big gap between the lofty aspirations and concrete proposals to implement these forward-looking elements. Rather than waiting until the publication of legislative proposals next summer and the accompanying impact assessment, it would be highly desirable if the Commission built on this Communication with a further series of think pieces spelling out its thinking in greater detail over the coming months. Crucial to the whole debate, of course, will be the Commission’s proposal on the financial parameters for the CAP post 2020 which is now expected on 29 May next year.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Photo credit: © Copyright Walter Baxter and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Europe's common agricultural policy is broken – let's fix it!