In a post last month, I made some estimates of the likely impact of Brexit on the CAP budget and which member states would have to stump up if overall CAP spending were to be maintained following a UK exit from the EU. These estimates were based on particular assumptions about how to calculate member states’ notional contributions to the CAP budget and how to calculate the CAP share of the overall UK rebate.

Of course, Brexit would have budgetary consequences not only for the CAP but for the UK net balance of contributions to all EU policies and for the overall EU budget. There has been controversy in the UK over the exact size of the UK’s net contribution to the EU budget (which, conversely, also represents the budget gap to be filled by the remaining member states if the level of EU spending in the remaining EU-27 countries and outside is to be maintained after Brexit).

In this post, I review the figures and their implications for the distribution of member state gains and losses from the EU budget assuming no change in overall EU expenditure in the EU-27 member states remaining after Brexit.

Why estimating the size of the UK net contribution can be tricky

Both the UK and the EU produce numbers on the UK net contribution to the EU budget. The UK numbers are produced annually by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) as part of its ‘pink book’ on the UK balance of payments (see Table 9.9 in the 2016 edition of the ‘pink book’ which can be downloaded here).

The UK Treasury also produces a table showing the UK net contribution to the EU budget in its annual statement on the EU budget (see the latest statement on the 2015 budget here). According to an ONS Perspectives briefing on the UK net contribution, “Their figures are very similar to those reported by the ONS as both use essentially the same data but due to some accounting differences there are some relatively small differences between the figures”.

However, both of these sources only measure flows to and from the UK public sector. These figures do not take into account EU funds which go directly to private sector entities in the UK (for example, to carry out research activities). Thus, to get a complete picture of the flows to and from the EU budget to the UK, it is necessary to use the DG BUDGET figures (in its spreadsheet Operating Balances of Member States). These EU figures show a smaller UK net contribution than the official UK sources.

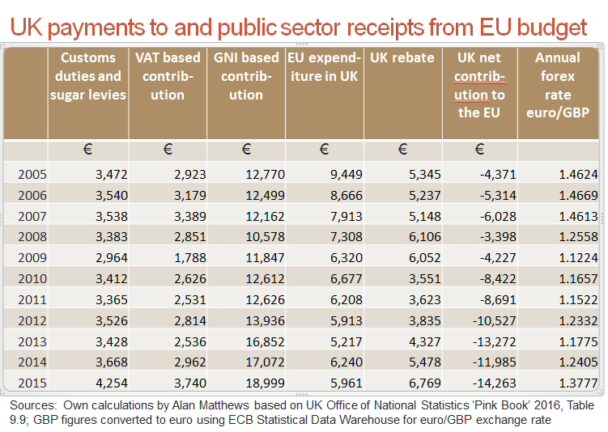

The ONS figures for EU flows to and from the UK public sector

I summarise the numbers and the trend over time from the ONS source in the table below. The UK figures are given in £ sterling. I have used the average sterling-euro exchange rate in each year to convert the net contribution figures in sterling to euro.

The net contribution fluctuates from year to year, and was particularly high in 2015 (especially when converted to euro because of the high value of sterling in that year). This was partly because of higher UK payments to the budget in 2015 (as explained in the previous post) but also because of a sharp fall in CAP Pillar 1 and regional fund receipts. Averaged over the previous four years, the UK net contribution from the public sector has been around €12.5 billion per annum.

According to the HM Treasury statement on the 2015 EU budget, EU receipts by the UK private sector amounted to around £1.4 billion (€1.65 billion) in 2013 so these should be deducted from the table above to get a more accurate picture. Surprisingly, however, there is no official UK source for UK payments to and total receipts from the EU budget, which no doubt partly accounts for some of the confusion around the correct figure in the Brexit referendum campaign.

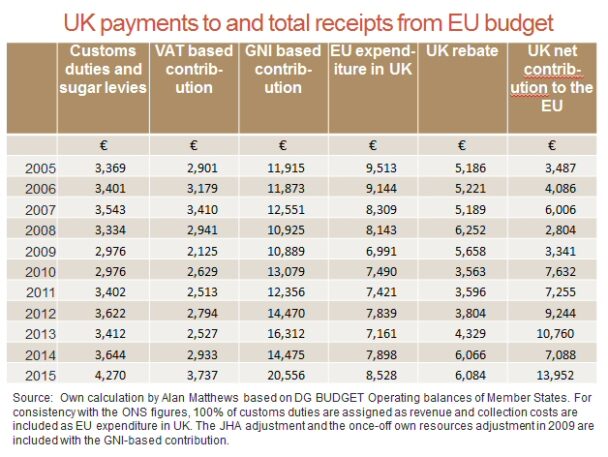

The DG BUDGET figures on the UK net contribution

The DG BUDGET figures are shown in the second table. The major difference, as expected, concerns the column for ‘EU expenditure in the UK’ which shows much greater figures than in the ONS table. There are also other differences, particularly with regard to the timing of payments for the GNI-based resource and the corresponding UK rebate in the last two years. Here the DG BUDGET figures show much lower GNI-based payments in 2014 but much higher payments in 2015.

For the technically-minded, the UK Treasury financial statement on the EU budget contains a technical annex (Annex B) which goes into detail explaining the differences between the UK government’s figures and those produced by DG Budget.

When the net contribution figures are averaged over the past four years, the average annual UK net contribution amounted to €10.3 billion compared to the ONS average figure of €12.5 billion solely taking account of public sector receipts. This €10.3 billion is a significant net transfer to the total expenditure in the remaining EU-27 member states of €138 billion.

The impact on member state net balances of Brexit

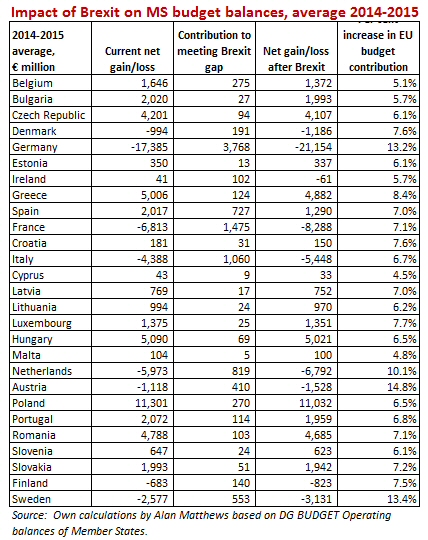

The final step is to ascertain how the burden of financing this gap in the EU budget would be shared among the remaining member states. To give an idea, we simulate what the impact on EU-27 member state net balances would have been if Brexit had occurred at the end of 2013 but the same level of EU spending was maintained in the remaining member states in the following two years 2014 and 2015.

The two year average is used because of the huge variation in the size of the UK net contribution in 2014 and 2015. The average turns out to be €10.5 billion, very similar to the four-year average of €10.3 billion over the period 2012-2015.

In order to finance this gap in revenue, I assume that member states make additional contributions to the EU budget according to their GNI-based contributions (as this is the marginal own resource which is called upon when member states must make additional payments to the EU budget). The GNI keys are derived from data in the relevant amending budgets submitted by DG BUDGET in 2014 and 2015.

The outcome of this hypothetical exercise is shown in the final table below. If the burden of financing the gap left by Brexit were borne proportionately by member states, it would imply an equal increase in the own resources contribution from each member state of around 7.5%.

The table tells a different story. It shows that four member states – Germany, Netherlands, Austria and Sweden – would be disproportionately called upon to finance the Brexit gap. Their payments to the EU budget would increase by between 10-15%. For all other member states, the increases in EU budget payments would be around half of this, between 5-8%.

The reason for this imbalance was explained in the earlier post. Although all member states currently contribute to the UK rebate or correction, these four countries have benefited from a ‘rebate on the rebate’. Brexit would mean the disappearance of this relative advantage and, in the absence of re-introducing another correction mechanism for these four countries, their payments to the EU budget will disproportionately increase if Brexit goes ahead.

Could Brexit lead to alternative sources of revenue?

Jorge Núñez Ferrer and David Rinaldi of the Centre for European Policy Studies in Brussels have made some similar calculations on the likely impact for the EU budget for Brexit although they arrive at somewhat different numbers to mine for the year 2014. However, they also point to two possible sources of revenue compensation which would help to reduce the financing burden on the remaining member states.

One suggested source of revenue compensation might arise if the UK entered into a European Economic Area (EEA)-type association with the EU. This would imply retaining all EU single market rules, including freedom of movement, and making a contribution to the EU budget as do EEA members Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. The CEPS authors estimate a UK contribution of €3.5 billion on a pro rata basis with Norway. However, only some of this money is paid to the EU budget in order to participate in specific EU programmes (such as Horizon 2020 and ERASMUS) or specific EU agencies (such as the European Chemicals Agency) and much of that money is returned to these countries in grants to their researchers or students.

The remainder of the money is disbursed directly through a separate EEA and Norway grants programme and is not paid into the EU budget. The UK may well agree to continue such payments after Brexit, but the net ‘surplus’ available to fund EU budget expenditure in the remaining EU Member States would be very small. (Update 7 Jan 2017: This paragraph and the previous one have been rewritten to correct the impression previously given that the EEA countries’ contribution to reducing economic and social disparities in the EEA area was paid directly into the EU budget).

The other possible source of revenue compensation assumes that the UK has no preferential trade relationship with the EU after Brexit and trades on Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariff terms. This would mean that the EU would now collect tariff revenue on imports from the UK after Brexit. Assuming just a 2% average tariff on UK imports, the CEPS authors estimate assuming unchanged trade flows that this could bring in an additional €4.6 billion.

Taking account of other flows, such as the fact that the UK may still be making payments on the basis of commitments entered into while still a member up until 2023, these authors conclude with a ‘no-catastrophe’ verdict for the EU budget in the aftermath of Brexit. While I broadly concur with this view, I am a little less sanguine, in part because I think the 2014 net contribution figure they use in their analysis may be on the low side as an indicator of what the UK net contribution might be in the future, and partly because of the strong skewness in the way the funding gap is likely to be distributed across countries, assuming overall EU expenditure is maintained.

Implications for the next MFF

Given the rising Euroscepticism in at least three of the four countries which will be asked to make the largest percentage increases in their payments to the EU budget following Brexit, whether these countries would be prepared to make this disproportionate additional contribution might be questioned. One solution would be to cap the additional contributions of these four countries, meaning that all other remaining member states would be asked to increase their payments even more. Or overall expenditure could be reduced.

Already, the EU is facing new challenges in terms of security and migration which will require additional resources to address. In the complex balancing act between increasing demands on the EU budget and fewer resources to finance these, it seems highly unlikely that either the CAP budget or the cohesion budget will emerge unscathed when the Commission makes it proposal on the next Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF) by the end of next year.

The vulnerability of the CAP budget in the negotiations on the MFF after 2020 will be well-known to readers of this blog. But I suspect the appetite to continue cohesion spending on its current scale in the future could also be much reduced.

One consequence of the ‘cultural counter-revolution’ in the EU called for by leaders in Poland and Hungary at their recent meeting will be a much-diminished sense of solidarity, especially in Germany, to continue to transfer significant amounts of cohesion and agricultural funding to these countries. (This link to a Bloomberg analysis is well worth reading in its own right).

Solidarity is not a one-way street. The unwillingness of some of the large net recipients of EU funds (see table above) to share in the co-operative solution of various EU challenges, notably management of the migration crisis, will not go unmarked in those countries making the payments.

It is all part of the messy post-Brexit world whose outlines we are only beginning to glimpse.

Note: A spreadsheet with the calculations is available here for those interested.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Picture credit. Italian Insider

Hi Alan,

This is a very interesting and well thought through assessment of the current situation, I for one believe the Brexit will have a galvanising effect on the 27 member states and their peoples. The Brexit British public and the politicians have not taken in to account public feeling on the continent with the mood of this country after the referendum and the weeks leading up to it.I anticipate port blockades of British goods and movement and this could have crippling effects.

Were the EU to open up talks with Russia on trade and get a quick deal it would soften the loss of trade with Britain.

My own company imports frozen bovine semen from the Netherlands and is having to absorb the currency effects of Brexit.I am unsure what tariffs I will face on imports once the plug is pulled on the single market.

I am of the opinion a lot of big business’ have covered their currency trading for the first 12 months of the vote and the real inflation will not happen for a while yet, when it does and imports and exports are threatened by blockades I can see the Country becoming bitter and twisted with it all.

Best regards,

Philip