The UK election has resulted in a resounding victory for the Conservative Party under Boris Johnson with its manifesto call to ‘get Brexit done’. The Conservatives won 365 seats, Labour 203, Scottish National Party 48, Liberal Democrats 11, the Northern Ireland Democratic Unionist Party 8, and other parties 15 seats giving the Conservative Party a thumping 80-seat majority.

One interpretation of the result is that a majority in the UK has now voted for Brexit. However, counting the votes cast instead of seats won shows a slight majority (52-48) voted in favour of parties that were opposed to Brexit or wanted a second referendum. The Brexit parties may have benefited from a general fed-upness and a sense that any decision was better than the no-decision option and the continuation of uncertainty offered by the Labour opposition. On this occasion, voters were better informed about the likely outcomes although the nature of an election rather than a single-issue referendum meant that voting decisions were also swayed by differences in support for the party leaders and the manifesto promises made on non-Brexit issues.

The political outcome means that, for the first time in three-and-a half years, a Eurosceptic Tory party purged of dissidents is now in control of Parliament and able to fulfil its manifesto promises. On Brexit, there are two key commitments:

- “We will start putting our deal through Parliament before Christmas and we will leave the European Union in January.

- We will negotiate a trade agreement next year – one that will strengthen our Union – and we will not extend the implementation period beyond December 2020. In parallel, we will legislate to ensure high standards of workers’ rights, environmental protection and consumer rights.”

We can thus presume that after six weeks the United Kingdom will no longer be an EU Member State (it is assumed that European Parliament approval of the Withdrawal Agreement following the UK Parliament is assured). The UK will enter the transition period foreseen in the Agreement on 1 February 2020 (if not before) which will continue until the end of December next year. This means that, broadly, the UK will continue to be treated as (and will have the obligations of) other Member States during this period though without voting rights.

The UK will continue to be part of a customs union and participate in the single market. This includes permitting free movement between the EU27 and the UK until the end of next year, and the European Court of Justice will continue to have jurisdiction as provided by the Treaties. It will continue to contribute to the EU budget and participate in common EU programmes with the exception of the direct payments scheme under the Common Agricultural Policy (Regulation 1307/2013) (Article 137 of the Withdrawal Agreement).

From the point of view of agricultural trade, this means there will be no immediate change in trading conditions in the coming year. However, decisions by the incoming UK government in the next twelve months will be important in setting the context for agricultural trade flows for the period after December 2020. At this point in time, the Conservative Party manifesto is the best guide to future policy developments, although the Queen’s Speech at the opening of Parliament next Thursday 19 December may provide further details.

In this post, I focus on the three most important policy areas to keep an eye on in the coming twelve months. These are the UK’s macroeconomic policy, its trade policy and its agricultural policy. Regulatory policy would be a potential fourth policy area but significant regulatory policy changes affecting agricultural trade were not announced in the Conservative Party election manifesto and are not expected in the coming twelve months.

Future macroeconomic policy

The fiscal policy that will be pursued by the new government and the monetary policy pursued by the Bank of England will influence agricultural trade through two channels: the overall level of demand in the UK and the sterling exchange rate that will influence the relative competitiveness of UK and EU products.

The incoming government has promised to ditch the austerity policies of its predecessors and is likely to embark on a significant spending spree. Considerable increases in current expenditure on schools, police, research, pensions and the national health service are likely. At the same time the government has promised not to raise income tax, national insurance or VAT rates while ruling out borrowing to fund current expenditure. The manifesto in addition promises an additional €100 billion in infrastructure spending which makes a lot of sense given low interest rates.

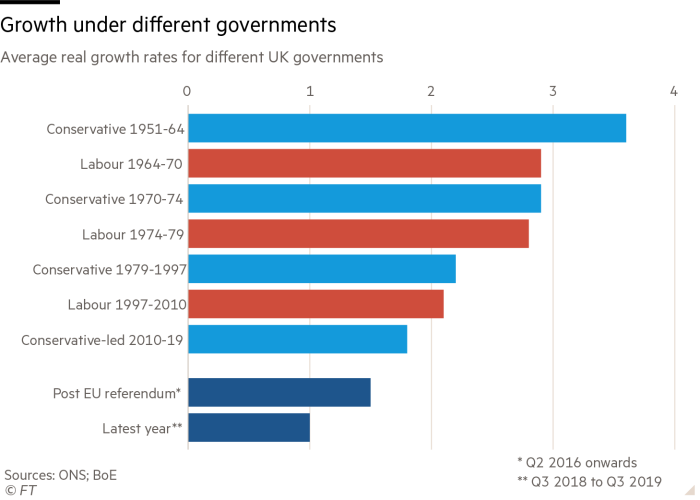

UK economic performance has been a mixed bag in recent years. On the one hand, economic growth rates have steadily declined (see chart from the Financial Times below), reflecting a dismal productivity growth rate. On the other hand, UK unemployment at 3.8% is well below most European economies with the exception of Germany (3.1%). The UK debt to GDP ratio has remained stubbornly high at around 84% while, despite attempts to rein in public spending under the Cameron and May governments, the general government balance remains in deficit to the tune of 1.9% of GDP. The UK also runs a deficit on its balance of payments current account of around 5% of GDP though this has narrowed to 4.6% in the latest quarter as stockpiling of imports due to Brexit uncertainty unwound.

Economic forecasts for the coming year are very divergent with some forecasters projecting that the UK will enter recession in 2021. However, the combination of fiscal stimulus and reduced Brexit uncertainty should support higher short-run growth in 2020 although at the cost of some worsening of the balance of payments and the public debt given the limited spare capacity in the economy and a further drop in inward migration.

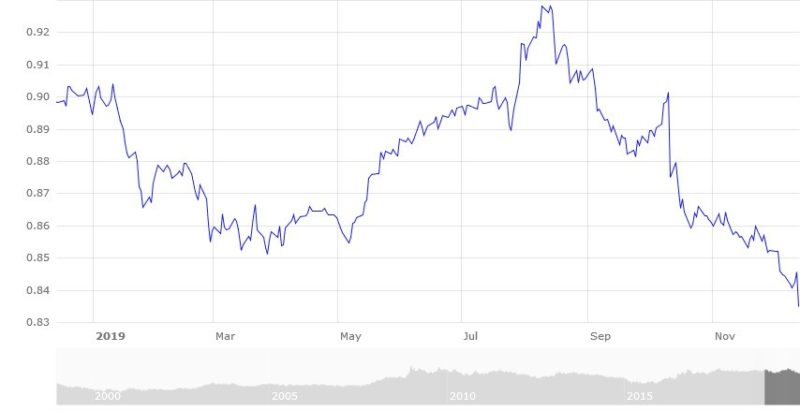

The likely trend in future exchange rates will depend in large part on future actions by the Bank of England. The general weakening in the value of sterling following the third defeat of Prime Minister May’s Withdrawal Agreement in March 2019 was reversed in August when the Bank of England raised interest rates from 0.5% to 0.75%. Sterling has continued to strengthen against the euro since then, especially in mid-October following agreement on a revised Withdrawal Agreement, and with a further jump to 83. 5 pence following the election result on 13 December. The ratification of the revised Withdrawal Agreement next month and the opening of negotiations on a free trade agreement with the EU should help to support the level of sterling through 2020.

Both somewhat stronger economic growth and a more competitive exchange rate should increase the attractiveness of the UK market in 2020 for EU agricultural exporters.

Future UK trade policy

The Conservative Party manifesto was not very specific on future trade policy. It set out a timeline for the conclusion of a free trade agreement with the EU without specifying what its negotiating objectives would be for that agreement. It declared the government’s intention is to have 80% of UK trade covered by trade deals within three years, including EU, US, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. But it said nothing about the baseline level of tariff protection it envisages in the absence of such agreements.

In the absence of any details to the contrary, one assumes that the Queen’s speech will reiterate the government’s intention to re-introduce the Trade Bill first introduced in the House of Commons in November 2017. One also assumes that the UK customs tariff after the end of the transition period will be that proposed as a temporary tariff regime in the event of ‘No-Deal’ in March 2019 (see this post for links to the source documentation for that tariff regime) and slightly updated in October 2019.

The best summary of the implications of this proposed tariff schedule for agricultural trade is this NFU Briefing Note. The tariff schedule itself was described as temporary in the event of a ‘No-Deal’ in 2019, to apply for up to 12 months until a long-term tariff regime was put in place. The intention was to put this in place following a full public consultation process.

The UK now has a further 12 months to consider whether it wants to alter this proposed temporary regime or not assuming it would now take effect from 1 January 2021. Keep an eye out for announcements by the Trade or Defra Ministers in the new Cabinet on the nature of any public consultation process in the coming months.

Prospects for the future EU-UK trade deal

As noted, the Conservative Party manifesto does not specify the UK’s objectives for its negotiations on a free trade agreement with the EU. The latest UK position is therefore contained in the revised and jointly-agreed Political Declaration attached to the revised Withdrawal Agreement negotiated in October 2019.

The EU position for the negotiations will be drawn up as negotiating guidelines by the Commission. The European Council (Art.50) at its meeting yesterday called on the Commission to prepare a draft of this mandate for approval by the General Council immediately after the UK’s withdrawal.

The Political Declaration calls for “an ambitious, wide-ranging and balanced economic partnership….encompassing a Free Trade Agreement, as well as wider sectoral cooperation where it is in the mutual interest of both Parties.” It will be underpinned “by provisions ensuring a level playing field for open and fair competition.” The Free Trade Agreement should ensure tariff-free trade across all sectors with appropriate and modern accompanying rules of origin, and with ambitious customs arrangements. Reference is also made to arrangements for financial services, digital trade, public procurement, transport, energy and fisheries, amongst other issues.

The European Council (Art. 50) conclusions yesterday underline the EU’s view that “The future relationship will have to be based on a balance of rights and obligations and ensure a level playing field.” Or as the Political Declaration puts it: “The precise nature of commitments should be commensurate with the scope and depth of the future relationship and the economic connectedness of the Parties.”

Unlike Theresa May, Boris Johnson has made clear that he wants the UK to be able to diverge from EU regulations in the future, although the Party manifesto does commit to legislation to ensure high standards of workers’ rights, environmental protection and consumer rights. How the UK will convince the EU side that this is sufficient to fulfil the ‘level playing field’ condition remains one of the open issues for the negotiation.

The manifesto insists that a free trade agreement must be completed and ratified within the eleven months of the transition period, given that it rules out making use of the option to seek an extension before 1 July 2020. This also points to a ‘bare-bones’ trade agreement involving just tariff-free and quota-free trade in goods as the most likely outcome, with possibly an agreement to continue talking about the more contentious issues such as access for financial services. But even this is unlikely to pass muster on the EU side, which will at least want fisheries access addressed as part of this initial phase.

Dominic Walsh of the Open Europe think tank has argued that, if more time is needed for negotiations, the UK and EU could agree to a new bilateral “standstill” agreement replicating all or some of the transition period. Alternatively, if a deal has been negotiated but more time is needed for ratification, then those aspects of the deal which are considered an EU competence could be applied “provisionally.” These stratagems could buy an extra few months but assume that the negotiations have otherwise made good progress.

A prospective ‘No-Deal’ scenario at the end of 2020

If the two parties fail to reach agreement by December 2020 then, in the absence of any request for extension before 1 July 2020, trade reverts to Most Favoured Nation (MFN) terms (also referred to as trade on ‘WTO terms’ or a ‘No Deal’ scenario). The implications for agricultural trade would then be exactly as projected if No-Deal had taken place in 2019.

However, as Dominic Walsh argues in the Open Europe blog previously cited, there are other implications of No Deal at the end of 2020 that are very different to the No Deal outcome in March 2019 without a Withdrawal Agreement in place. He emphasises that “’No trade deal’ is not the same as ‘No Withdrawal Agreement’”.

By the end of January 2020, the Withdrawal Agreement will have been ratified. This means that, even if no trade deal has materialised by the end of next year, citizens’ rights, the UK financial obligations to the EU and the arrangements set out in the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol for the avoidance of a hard border on the island of Ireland will be secured (with consent for the latter to be tested in the Northern Ireland Assembly from 2024).

The Protocol is particularly important for maintaining, inter alia, agricultural trade on the island of Ireland. It provides for tariff-free trade between Northern Ireland and the EU, along with full regulatory alignment on goods, to avoid the need for checks and controls at or near the land border even in the event of No-Deal. However, as Dominic Walsh has pointed out in another post: “… although the Protocol would be legally operational in this scenario, there may be questions over its practical functioning in the absence of a wider UK-EU trade deal. If Northern Ireland and Great Britain have fundamentally different trading relationships with the EU, this will have implications for the extent of East-West barriers to trade in the Irish Sea”.

Future UK agricultural policy

The Conservative Party manifesto is clearer about what it proposes for future UK agricultural policy, essentially confirming the provisions in the lapsed Agriculture Bill which again, presumably, will be reintroduced in the next Parliament as part of the Queen’s Speech. The commitments made in its post-Brexit deal for farming are the following:

- “Once we have got Brexit done, we will free our farmers from the bureaucratic Common Agricultural Policy and move to a system based on ‘public money for public goods’.

- To support this transition, we will guarantee the current annual budget to farmers in every year of the next Parliament.

- In return for funding, they must farm in a way that protects and enhances our natural environment, as well as safeguarding high standards of animal welfare.

- When we leave the EU, we will be able to encourage the public sector to ‘Buy British’ to support our farmers and reduce environmental costs.

- We will increase the annual quota for the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme we are piloting from 2,500 to 10,000.

- We will invest in nature, helping us to reach our Net Zero target with a £640 million new Nature for Climate fund. Building on our support for creating a Great Northumberland Forest, we will reach an additional 75,000 acres of trees a year by the end of the next Parliament, as well as restoring our peatland”.

The key commitment here is to maintain current funding levels for farmers in the next five years, but to move over time to a system of paying public money for public goods. This radical proposal to move away from per hectare land-based subsidies (as least for England, as Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have responsibility for their own agricultural policies) stands in stark contrast to the timidity of the changes to the CAP post 2020 currently under discussion (I previously discussed the differences between the Commission’s proposed changes to the CAP post 2020 and the UK’s post-Brexit approach in this post).

While the details of the policy have yet to be worked out, the longer-term implications will be a smaller UK food production sector with farmers receiving a greater share of their overall revenue in the form of payments for environmental services. In the absence of compensating changes in consumption through dietary change, the UK will likely become more reliant on imports. With its proposed much more liberal tariff schedule, a higher share of these imports will be sourced from non-EU third countries, even in the context of continued free trade with the EU in agri-food products under a free trade agreement.

Conclusions

Agricultural trade between the UK and the EU will operate under two different regimes in 2020 and in the years thereafter. In 2020, it will be governed by the transition provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement which essentially maintains the trading status quo. The main impact on agricultural trade flows to the UK during this period will be the growth in UK demand, which in turn will be influenced by macroeconomic policy, and the euro-sterling exchange rate. Both somewhat stronger economic growth and a more competitive exchange rate should increase the attractiveness of the UK market in 2020 for EU exporters.

The picture after 2021 will be different. Even if the reintroduction of tariffs on UK-EU trade is avoided by a free trade agreement, EU exporters will face higher non-tariff costs of exporting as well as greater competition on the UK market due to the UK’s liberalised tariff schedule. This will be offset by a likely contraction of UK food production due to import competition and the start of the shift to restructured agricultural payments (an important unknown here is the extent to which lower direct income support will stimulate farm restructuring and an overall increase in technical efficiency and productivity).

While these two effects offset each other and the net outcome will be an empirical matter, the most likely outcome of the UK election result for agricultural trade is that EU exports will lose market share on the UK market once the transition period ends on 1 January 2021. Unfortunately, none of the published studies of the impact of Brexit on UK agriculture have as yet been updated to take into account both the significant liberalisation of UK trade policy implied by the March 2019 tariff schedule or the likely production effects of the shift from area-based direct payments to payments for public goods. This would be a useful exercise to undertake in 2020.

This post was written by Alan Matthews